Belisarius[2] (Latin pronunciation: [bɛ.lɪˈsaː.ri.ʊs]; Greek: Βελισάριος; c. 500[Note 2] – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean territory belonging to the former Western Roman Empire, which had been lost less than a century prior.

One of the defining features of Belisarius' career was his success despite varying levels of available resources. His name is frequently given as one of the so-called "Last of the Romans". He conquered the Vandal Kingdom of North Africa in the Vandalic War in nine months and conquered much of Italy during the Gothic War. He also defeated the Vandal armies in the battle of Ad Decimum and played an important role at Tricamarum, compelling the Vandal king, Gelimer, to surrender. During the Gothic War, despite being significantly outnumbered, he and his troops recaptured the city of Rome and then held out against great odds during the siege of Rome.

After a setback at Thannurin, he won a battle against the Persians at Dara but was defeated at Callinicum. He successfully repulsed a Hunnish incursion at Melantias. He was also known for military deception; he repulsed a Persian invasion by deceiving their commander and lifted the siege of Ariminum without a fight.

Early life and career

Belisarius was probably born in Germania, a fortified town of which some archaeological remains still exist, on the site of present-day Sapareva Banya in south-west Bulgaria, within the borders of Thrace and Paeonia, or in Germen, a town in Thrace near Orestiada, in present-day Greece.[3] Born into an Illyrian,[4][5][6][7] Thracian,[8] or Greek[9][10] family, he became a Roman soldier as a young man, serving in the bodyguard of Emperor Justin I.[11]

After coming to the attention of Justin and Justinian as an innovative officer, he was given permission by the emperor to form a bodyguard regiment. It consisted of elite heavy cavalry[12] that he later expanded into a personal household regiment, 7,000 strong.[13] Belisarius' guards formed the nucleus of all the armies he would later command. Armed with lances, (possibly Hunnish style) composite bows, and spatha (long sword), they were fully armored to the standard of heavy cavalry of the day. A multi-purpose unit, the Bucellarii (biscuit-eaters) were capable of shooting at a distance with bows, like the Huns, or could act as heavy shock cavalry, charging an enemy with lance and sword. In essence, they combined the best and most dangerous aspects of both of Rome's greatest enemies, the Huns and the Goths.[14]

Iberian War

In his early career, Belisarius participated in multiple Byzantine defeats. In the first battle where he held an independent command (together with Sittas, most likely a dual command) he suffered a clear defeat,[15] but he and Sittas were noted as successful raiders, plundering Persian territory,[12] for example, during the first invasion of Persarmenia of the war, taking place shortly before.[15] The next battle was fought at Tanurin (south of Nisbis[16]), where Belisarius played a leading role again. He fled with his troops after his colleagues were lured into a trap. His army was then defeated at Mindouos, but he was promoted shortly afterward, meaning he was not likely held responsible for the defeat. At first, he was likely a junior partner to some higher placed commander like Sittas, while at Thanurin there was no overall commander. Mindouos was probably the first battle in which he led the army entirely on his own.[15]

Following Justin's death in 527, the new emperor, Justinian I, appointed Belisarius to command a Roman army in the east, despite earlier defeats.[15] In June/July 530, during the Iberian War, he led the Romans to a stunning victory over the Sassanids in the Battle of Dara.[12][13][17][18]: 47–48 This victory caused the Persian king Kavad I to open peace negotiations with the Byzantines.[18]: 47–48 At the battle Belisarius had dug trenches in order to direct the more mobile Sassanian force to a location where he could attack them from the rear,[12][13] this was adopted from the Sasanians at Tanurin two years earlier.[19]

On other fronts, the Byzantine forces were also winning. The Persians and their Arab allies, with a mobile force of 15,000 high-quality cavalries, invaded Byzantine lands again, now via Euphratensis, a route they had never taken before. Belisarius was taken by surprise and was unsure whether this was a feint or a real attack, so at first, he did not move. He called upon Roman-allied Arab tribes for help and received 5,000 troops. He forced the Persians to retreat with a successful strategic maneuver but he kept pursuing the fleeing Persians, reportedly because his soldiers threatened mutiny if no battle was fought. With 20,000 Byzantines and 5,000 Arabs he moved against the Persians, but he was defeated by Callinicum (modern Raqqa)[18]: p. 48 despite heavy numerical superiority, as the opposing commander, Azarethes, was a tactician as good as himself.[20] Belisarius fled the field probably long before the fighting was over. This setback cost Justinian a chance to sign an early peace treaty as the shah regained confidence in the war effort. While the war went on after Dara and Callinicum, the death of the Persian shah, Kavad I, soon led to a peace treaty. The new shah, Khosrow, saw Justinian was anxious to sign for peace and thought he could quickly reach a favorable peace, such as the so-called eternal peace which heavily favored the Persians. Belisarius was recalled to Constantinople and charged with incompetence and responsibility for the defeats at Thannuris and Callinicum, but after an investigation, he was cleared of the charges against him.[13]

Nika riots

In Constantinople, Justinian had been carrying out reforms of the empire. In this, he had been assisted by John the Cappadocian and Tribunianus, who were corrupt.[15] The corruption of John and Tribunianus;[18]: 49 the curbing of corruption of other influential figures; loss of influence and employment because of a decrease in funding for the civil service; Justinian's low birth; extremely high taxes;[18]: 49 [21] cruel methods of tax collection;[12] the curbing of the power of the chariot racing factions; and the execution of rioters[18]: 49 led to great anger among the population, culminating in the Nika riots of 532. The riots were led by the chariot racing factions—the blues and the greens. At the time the riots broke out, Belisarius was in Constantinople. Belisarius, Mundus—the magister militum per Illyricum[22]—renowned as a great commander, and Narses, a eunuch and confidant of Justinian who would later also be known as a great commander, were called upon to suppress the revolt. At this point, much of the city had been burned by the rioters, but the blue faction began to calm down, and after Narses distributed gifts to them, many returned home[13] while others began spreading moderate views among the other rebels. Belisarius tried to enter the hippodrome, where the rioters were gathered, through the emperor's box but was blocked by its guards. Belisarius was surprised and informed Justinian, who ordered him to enter from another direction. Entering the hippodrome, he wanted to arrest Hypatius, who was declared emperor by the rioters. Hypatius was defended by guards who Belisarius would first need to eliminate, but if he attacked, the rioters would be at his rear. Belisarius decided to deal with the rioters and, bypassing the door to Hypatius' location, charged into the crowd. Mundus, hearing the sound of battle, also charged while Narses blocked the other exits in order to trap the rioters. Thus the revolt ended in a massacre. At least 30,000[Note 3] and up to 60,000[12] died, mostly unarmed civilians.

Vandal War

Prelude

In 533, Belisarius began a campaign against the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa.[15] The Byzantines had political, religious, and strategic reasons for such a campaign. The Vandals, being Arians, persecuted Nicene Christians, refused to mint coins with depictions of the emperor on them, and had banished the Roman nobility, replacing them with a Germanic elite. The recent Byzantine emperors had spent much effort on reunifying pro-Chalcedonian and anti-Chalcedonian Christians and uniting the eastern and western parts of the church,[13] so the prosecution of "good" Christians by Arian heretics was an especially big issue. The persecution had started after the popular and successful Vandal military leader Gelimer had overthrown his cousin, the king, Hilderic, a childhood friend of Justinian, in the year 530. In a recent war against the native Berbers, the Vandals had lost 5,000 men in two decisive defeats; only when Gelimer was appointed commander did the tide shift.[Note 4] As king, Gelimer acquired a reputation for greed and cruelty and became unpopular with the people and nobility. Two revolts broke out at nearly exactly the same time, probably orchestrated by Justinian.[12] With a large number of Vandals killed by the Berbers, and the Ostrogoths still angry because of the actions of Hilderic, the Vandals were perceived to be weak.[18]: p.52 Using the fact that Gelimer had defied him, and the pleas of African Catholics as justification, Justinian sent an invasion force.

Belisarius appointed

There were multiple reasons to choose Belisarius to lead such an expedition.[15] He had shown military competence at Dara, been cleared of incompetence in his other battles by an inquiry, and was a friend to the emperor and thus obviously loyal to him. As an inhabitant of Germana, which was in or near Illyricum and west-oriented, and a "native" speaker of Latin, he wasn't considered an untrustworthy Greek by the natives. Belisarius was reappointed Magister Militum per Orientem and given command of the expedition. This time Belisarius would be free from dual command for the duration of the war.

Belisarius' army

The expedition consisted of 5,000 high quality Byzantine cavalry under multiple commanders,[15] 10,000 infantry[12][13][18]: p.52 [23] under overall command of John of Epidamnus, Belisarius' guard, mercenaries (including 400 Heruls[12][13] led by Pharas, noted by Procopius for their excellence, and 600 Huns[12][13] under multiple commanders) and finally a contingent of foederati of unknown size led by Dorotheus, Magister Militum per Armeniam, and Solomon, Belisarius' domesticus. As praetorian prefect, in charge of the logistics of the army, Belisarius got Archelaus,[13] an extremely experienced officer, in order to lighten the burden of command. In total the force is estimated to have been around 17,000 strong, while 500 transport ships[12][13] and 92 warships[12][13] crewed by 30,000 sailors[13] and 2,000 marines were also put under Belisarius' command. While it is the view of many that Belisarius set sail for North Africa with "only" 15,000 soldiers to conquer the region, his force included more troops and many sailors. It was a well balanced force with quite possibly a larger percentage of high-quality troops than the armies facing Persia. Gelimer probably had only 20,000 men at his disposal at this time[13] and his force had no horse archers or units fit to fight them, and he had fewer[12] and lower-quality officers.

Voyage to Africa

In June 533, the army embarked from Constantinople.[15][12] On the expedition alcohol was forbidden.[12] When on the way two drunken Huns killed another soldier, Belisarius had them executed to reinforce discipline.[12][13] Such a cruel measure might have undermined his authority and given him the reputation of a cruel leader, but he prevented negative repercussions with a speech.[12] Belisarius had the staff-ships marked and lanterns put up so that they would always be visible. The use of signals kept the fleet organized and sailing close together, even at night, and was praised heavily by Procopius.[13]

By the time they arrived at Sicily, 500 men had died after eating improperly prepared bread.[13]: p.120 Belisarius quickly acquired fresh bread from the locals. He would make several extra stops during his journey to acquire extra bread during the voyage.[12] In Methone he also organized his forces. Before the Byzantines could cross over to Gothic Sicily, where they were allowed to stop on their way to Africa by the pro-Byzantine, anti-Vandal queen Amalasuntha, they had to cross the Adriatic Sea. Despite acquiring fresh water, the weather caused the water supply to spoil before arrival, and only Belisarius and a select few others had access to unspoiled water. In Sicily Procopius was sent to acquire supplies from Syracuse and gather intelligence about the Vandals' recent activities.[12][13] There he found out that the Vandals had taken no measures to defend against a Byzantine invasion, and in fact were unaware one was coming.[12][13][Note 5] Procopius also found out that most of the Vandal fleet was occupied around Sardinia.[12][13]

At this point Dorotheus died and Belisarius and his troops were demoralized, but when they heard Procopius' discovery they quickly left for Africa. In total, unfavorable winds had protracted their journey to 80 days.[18]: pp.52–53 Despite the long duration, the journey went better than that of any other Roman invasion of Vandal Africa; all three others ended before reaching the coast.[13] During and before the journey to Africa, Belisarius had no chance to personally train his units, which would make his campaign in Africa more difficult.[12] This was in contrast to his campaign in the east; unit cohesion was especially lacking during this invasion.

While the full conquest of Africa is often portrayed as the original objective of the campaign, it is unlikely this was actually the case.[13] Belisarius had the full authority to act in any way he saw fit.[13] Only when Belisarius was already in Sicily was the choice made to sail straight for the Vandal heartland.[13] If the Vandal fleet had been ready, such an operation would have been unlikely to succeed.[13] When information arrived in Constantinople it was already weeks, if not months, old, so it seems unlikely that Justinian in Constantinople would have made the decision on whether to move on the area at all.[13] Only at Sicily would one be in any kind of position to decide on how to proceed.[13]

Since Justinian had been reluctant to launch a campaign in the first place and Hilderic was still alive at this point, conquest seems not to have been the absolute intention.[13][Note 6] On the other hand, Justinian had lost almost all of his prestige and much of his power through defeat by Persia, the Nika riots, the slow progress of the current legal reforms and the failure of his quest for reconciliation in the church.[13] He would need some kind of victory to repair his prestige.[13] Capturing the undefended region of Tripolitania, which lacked Vandal settlement almost entirely, was currently rebelling, and whose vulnerability could be detected from Constantinople, would be such a victory.[13] As such, this seems likely to have been his minimal demand.[13] If successful, the Byzantines could use this region as a springboard to conquer the entire country[12] later on, giving an extra reason to make it the minimal demand of the campaign. As such, it is Belisarius' decision at Sicily that initiated Justinian's reconquest.

Campaign

With Gelimer being four days inland and his troops scattered, Belisarius could have taken Carthage before the Vandals even knew he was coming and certainly before they were in a position to react.[15][Note 7][Note 8] Archelaus argued in favor of this approach, pointing out that Carthage was the only place in the Vandal Kingdom which had a fortified harbor.[13] Belisarius considered potentially being cornered in Carthage, with the Vandals holding a superior naval position, his forces vulnerable to attack when landing, and no information on the position of the Vandals to be too dangerous.[12] There also was the risk of unfavorable winds which had led to disaster in 468; they might be trapped in an unfavorable situation before even reaching Carthage.[13] Instead the Byzantines landed at Caput Vada,[12][13][18]: pp52–53 162 miles (261 km) away from Carthage.[12]

Belisarius ordered fortification to be constructed, guards to be posted and a screen of lightships to be deployed to defend the army and fleet, so that this invasion would not be a repeat of the Battle of Cape Bon where the Byzantines were defeated by fire ships. During the construction of the base, a spring was found, which Procopius called a good omen from God.

When he heard of the Byzantine landing, Gelimer rapidly moved to consolidate his position.[15] He had Hilderic[13] and other captives executed, ordered his treasury to be put on a ship ready for evacuation to Visigothic Iberia if necessary, and began gathering his troops.[13] He had already made a plan to ambush and encircle the Byzantines at Ad Decimum. Gelimer had instantly recognized that the Byzantines would move to Carthage via the coastal road, but still sent garrisons to guard other roads.

At the same time that Gelimer was preparing his ambush, Belisarius was gathering information on the local inhabitants and preparing to move to Carthage via the coastal road, as Gelimer expected.[15] During the first night on African soil, some Byzantine soldiers had picked some fruit without asking the locals for permission, and Belisarius had them put to death. Only after he had already ordered the soldiers to be executed did Belisarius gather his men and tell them how to behave. He warned his men that if they didn't have the support from the locals, the expedition would end in defeat. Next, he sent a unit of his personal guards under Boriades to the town of Syllectus (Salakta) to test the willingness of the locals to join his side. Boriades was denied entry to the town, but after three days eventually gained entry by joining a group of wagons entering the town. When the locals found out the Byzantines were in the town, they submitted without a fight. The Byzantines also captured a Vandal messenger who Belisarius decided to release. The messenger was paid to spread the message that Justinian was only waging war on the man who had imprisoned their rightful king, and not against the Vandal people. The messenger was too afraid of the possible repercussions to tell it to anyone but close friends. Even though this early attempt failed, Belisarius made it well known throughout the campaign that he was only there to restore the rightful king.[13]

When Belisarius advanced again, he positioned his troops in such a way that he and his guards could rapidly reinforce any position that could be attacked, especially the flank, as the last known Vandal position was to the south and the army moved north.[15] He also sent 300 guards[Note 9] ahead to scout while the 600 Huns[Note 10] guarded his left flank, and the fleet his right flank. When the army arrived in Syllectus, their civilized behavior caused the city to give their full support to the Byzantines. This positive reputation of the Byzantine army began immediately spreading, causing much of the population to support the Byzantines. Marching at the speed of around 7 miles (11 km)[12] to 9 miles (14 km)[15] a day, the Byzantines advanced on Carthage, their speed dictated by the need to build a fortified camp every day.[12]

When Belisarius was 40 miles (64 km) away from Carthage, he knew the Vandals would be near at this point[15] and that they would act before he could reach Carthage,[12] but he was not aware of the location and wanted to gather information of his situation first. Part of the rearguard encountered a Vandal force sent ahead by Gelimer, which gave Belisarius the knowledge that at least some Vandal troops were behind his own force. His journey now became increasingly dangerous as the fleet had to sail around Cape Bon and the road curved inland so it became impossible to rapidly evacuate, which he could have done at any time he wanted until this point.[12] Belisarius ordered Archelaus and the naval commander Calonymus remain at a distance of at least 22 miles (35 km) from Carthage. He advanced on land with about 18,000 men himself. Soon he would encounter Gelimer at Ad Decimum.[12]

Battle of Ad Decimum

The Byzantines were located in between the Vandal forces in the north and the south.[15] Gelimer needed a victory at Ad Decimum to unite his forces. Numbering about 10,000–12,000, the Vandals were outnumbered. The valley in which the ambush was to take place was narrow, and as two of the three roads to Carthage became one in the valley, it seemed like a great spot for an ambush to Gelimer. Ammatus, with 6,000–7,000 men, was ordered to block the northern exit and attack the Byzantines head-on, then drive them further back into the valley and cause disorder. Meanwhile, 5,000–6,000 Vandals under Gelimer were already advancing towards Belisarius from the south as the earlier clash showed; these would be in the near vicinity when Belisarius entered the valley and would attack them from behind, after all the Byzantines had moved into the valley. Brogna states that this plan was doomed to fail, as coordination over dozens of miles was needed,[12] however, Hughes disagrees and calls the plan "elegant and simple", but does state that the plan relied too much on hard to pull off timing and synchronization.

The battle consisted of four separate stages.[15] Four miles (6.5 km) from Ad Decimum, Belisarius found an ideal spot to camp. Leaving the infantry behind to build a camp, he rode out with his cavalry to meet the Vandals who he suspected were nearby. This way he left his infantry, baggage, and wife in a secure position.[12] Unlike the large infantry force, he would easily be able to control this small force of cavalry,[12] which was the main strength of the Byzantine army.[12] When Belisarius arrived at the battlefield, the first three stages of the battle had already taken place. The Byzantines sent ahead to scout and the Huns guarding the flank had routed the numerically superior forces opposing them.[13] Before Belisarius arrived at the field of battle, he encountered some units routed by Gelimer's army, who informed him of the situation in the third stage, when Gelimer himself arrived. As Belisarius arrived, Gelimer saw his brother Ammatus killed in combat. Mourning, he remained idle and allowed Belisarius to attack his force while it was in a disorganized state in the fourth and last stage of the battle.

Carthage and Tricamarum

After this victory, Belisarius marched on Carthage.[15][12][18]: p.53 He arrived at nightfall.[13] He then camped outside the city as he was afraid of a Vandal ambush in its streets and of his troops sacking the city under the cover of darkness.[13] When Calonymus heard of the victory, he used part of his fleet to rob a number of merchants. Belisarius ordered him to give everything back, even though Calonymus secretly managed to keep it.[Note 11] The Vandals hiding in Carthage and the surrounding area were gathered in Carthage by Belisarius, who guaranteed their safety.[13] When Tzazo, the Vandal commander fighting the rebellion on Sardinia, sent a message of his victory to Carthage, the messenger was captured, providing Belisarius with intelligence on the strategic situation. Belisarius also had Carthage's wall repaired.[13] The news of the capture of Carthage had reached Iberia by then, and its king refused to make an alliance with the envoy Gelimer had sent earlier.[13] Due to Belisarius' benevolence, many cities of Africa changed sides, so it became impossible for Gelimer to fight a protracted campaign. Before making his next move, Gelimer had received reinforcements under Tzazo and tried to convince some of Belisarius' forces to desert. Belisarius prevented their desertion, but for example, the Huns would not take part in the battle until after the winner had been practically decided. When a Carthaginian civilian was caught working for the Vandals, Belisarius had him publicly executed.[13]

Later a second battle was fought at Tricamarum.[15] In this battle, Belisarius played only an advisory role to John the Armenian as he arrived at the battlefield later on. After winning that battle, Belisarius sent John the Armenian to chase Gelimer. John was killed by accident and Gelimer managed to escape to Medeus, a town on Mount Papua (probably part of Mount Aurasius)[24] The 400 Heruls under Pharis were to besiege it. Gelimer's treasure failed to depart and was captured and the king of the Visigoths, Theudis, refused an alliance with Gelimer. After a failed assault in which Pharis lost 110 men, Gelimer surrendered. Meanwhile, Belisarius himself had been reorganizing the captured territory and had sent Cyril on a mission to capture Sardinia which would capture that island, and later also Corsica. The effort to locate and gather Vandal soldiers was still going on; in this way, the class on which the entire Vandal military and political systems were based could be wholly deported to the east and Vandal power forever broken.[13] Jealous subordinates now contacted Justinian and claimed Belisarius wanted to rebel.[Note 12] Belisarius was presented with a choice by Justinian: he could either continue governing the new territory as its official governor or return to Constantinople and get a triumph. If he wanted to rebel he was sure to choose the governorship, but instead he chose the triumph, convincing Justinian of his loyalty once again. The entire war was over before the end of 534.

While east, Belisarius was not only awarded a triumph but also made consul.[13][18]: p.54

Mutiny

Sometime after Belisarius left, a mutiny broke out in Africa.[15] Soldiers angry about religious persecution by the Byzantines, and the inability of the empire to pay them, rose up en masse and nearly broke Byzantine rule in the area. Belisarius would return for a short while, just before the Gothic War, to help fight the revolt. When the rebels heard of his arrival, they lifted the siege of Carthage, which at the beginning of the siege had numbered 9,000 plus many slaves. Belisarius attacked them with just 2,000 troops, winning a victory in the Battle of the River Bagradas. During the battle, Stotzas, the rebel leader, tried to move his army into a new position in front of the Byzantine force. When the units moved, Belisarius took advantage of their temporary disarray and launched a successful attack against them, which caused the entire rebel army to panic and flee. The rebels' power was broken and Belisarius left for Italy.

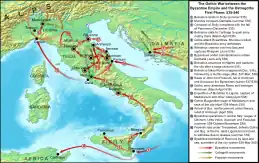

Gothic War

In 535, Justinian commissioned Belisarius to attack the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy. The Ostrogothic king Theodahad had gained the throne by marriage.[15][18]: p.55 [23] Power had been held, however, by the pro-Byzantine queen Amalasuintha, until Theodahad had her imprisoned and then killed.[18]: p.55 Seeing internal division similar to that in Africa, Justinian expected the Goths to be weak.[23] Belisarius assembled 4,000 troops, which included regular troops and possibly foederati, 3,000 Isaurians,[18]: p.55 300 Berbers and 200 Huns.[23][Note 13] In total, including his personal guards, his force numbered roughly 8,000.[12] Belisarius landed in Sicily and took the island in order to use it as a base against Italy, while Mundus recovered Dalmatia.[12][25] Justinian wanted to pressure Theodahad into relinquishing his throne and to then annex his kingdom through diplomacy and limited military action.[12] This worked at first, but the army in the Balkans retreated.[Note 14] and the war continued. Belisarius pushed on in Sicily. The only Ostrogothic resistance came at Panormus, which fell after a quick siege.[Note 15] Here Belisarius used archer fire from the top of the masts of his ships to subdue the garrison.[12][26][27] He made a triumphal entry to Syracuse on 31 December 535.[27] The preparations for the invasion of the Italian mainland were interrupted[18]: p.56 in Easter 536 when Belisarius sailed to Africa to counter an uprising of the local army (as described above).[27] His reputation made the rebels abandon the siege of Carthage, and Belisarius pursued and defeated them at Membresa.[27]

Afterwards he returned to Sicily and then crossed into mainland Italy, where he captured Naples in November and Rome in December 536.[28] Before reaching Naples, he had met no resistance as the troops in southern Italy were disgusted by Theodahad and switched sides.[18]: p.56 At Naples a strong Gothic garrison resisted the Byzantines using its strong fortifications.[12] Belisarius could not operate safely at Rome with such a strong garrison in his rear.[12] He could neither storm the strong fortifications nor conduct a lengthy siege which could be interrupted by Gothic reinforcements, while bribery and negotiation attempts also failed.[12] He couldn't use his fleet either as there was artillery on the wall. Then Belisarius cut the aqueduct, but the city had enough wells, so he resorted to making many costly, failed assaults. After their failure, Belisarius planned on abandoning the siege and marching on Rome. By chance, however, an entrance to the city via an aqueduct was found and a small Byzantine force entered the city.[Note 16]

When this force had entered the city, Belisarius launched an all-out assault so the Goths couldn't concentrate against the intruders. Despite having taken the city by force, he showed leniency to the city and garrison, so as to entice as many other Goths to join his side or surrender later on; this way he would avoid costly action as much as possible and preserve his small force.[12] The failure to reinforce the city caused Theodahad to be deposed. While the new Gothic king, Vitiges, had sent a garrison to Rome, the city was left undefended as the troops fled after noticing the pro-Byzantine attitude of the population.[12] Much of Tuscany submitted willingly to Belisarius' troops at this point.[29] Belisarius garrisoned towns on the supply lines from the Gothic heartland in the north to Rome, forcing Vitiges to besiege these towns before he could march on Rome.[12]

Siege of Rome

From March 537 to March 538 Belisarius successfully defended Rome against the much larger army of Vitiges.[15] He inflicted heavy casualties by launching many successful sorties. While the range of the horse archers Belisarius used has often been credited with the success of these raids in the terrain around Rome, this wouldn't make sense. Instead, it was the Gothic unpreparedness and the command expertise of Byzantine officers which made sure the Goths were unable to respond. When Vitiges tried to post units to prevent these raids, Belisarius sent out bigger units that encircled them; the Gothic officers proved unable to counter this. Eighteen days into the siege,[12] the Goths launched an all-out assault, and Belisarius ordered a number of archers to shoot at the oxen pulling the siege equipment. As a result, the assault failed with heavy casualties.[12]

When the Goths retreated from a certain section of the wall, Belisarius launched an attack on their rear, inflicting extra casualties.[12] However, when he tried to end the siege by sallying out with a large force, Vitiges used his numbers to absorb the attack and then to counter-attack, winning the battle. Regardless, Vitiges was losing the siege, so he decided to make one last attempt on the wall which ran along the Tiber, where the wall was much less formidable. He bribed men to give the guards drugged wine, but the plot was revealed and Belisarius had a traitor tortured and mutilated as a punishment. An armistice had been signed shortly before, but with both the Goths and the Byzantines openly breaking it, the war continued. By then Byzantine forces had captured Ariminum (Rimini)[30] and approached Ravenna, so Vitiges was forced to retreat.[30] The siege had lasted from March 537 to March 538.

Belisarius sent 1,000 men to support the population of Mediolanum (Milan) against the Goths.[15] These forces captured much of Liguria, garrisoning the major towns in the region. Belisarius captured Urbinum (Urbino) in December 538, when the Gothic garrison ran out of water after a three-day siege.[31]

Deposition of Pope Silverius

During the siege of Rome, an incident occurred for which the general would be long condemned: Belisarius, a Byzantine Rite Christian, was commanded by the monophysite Christian Empress Theodora to depose the reigning Pope, who had been installed by the Goths.[32] This Pope was the former subdeacon Silverius, the son of Pope Hormisdas.[32][33][34] Belisarius was to replace him with the Deacon Vigilius,[32] Apocrisarius of Pope John II in Constantinople.[35] Vigilius had in fact been chosen in 531 by Pope Boniface II to be his successor, but this choice was strongly criticised by the Roman clergy and Boniface eventually reversed his decision.

In 537, at the height of the siege, Silverius was accused of conspiring with the Gothic king[32][36] and several Roman senators to secretly open the gates of the city. Belisarius had him stripped of his vestments and exiled to Patara in Lycia in Asia Minor.[32] Following the advocacy of his innocence by the bishop of Patara, he was ordered to return to Italy at the command of the Emperor Justinian, and if cleared by investigation, reinstated.[34][36][Note 17] However, Vigilius had already been installed in his place. Silverius was intercepted before he could reach Rome and exiled once more, this time on the island of Palmarola (Ponza),[32][36] where by one account he is said to have starved to death,[32][36] while others say he left for Constantinople. However that may be, he remains the patron saint of Ponza today.[36]

Belisarius, for his part, built a small oratory on the site of the present church of Santa Maria in Trivio in Rome as a sign of his repentance.[37] He also built two hospices for pilgrims and a monastery, which have since disappeared.

Belisarius and Narses

Belisarius ordered the cavalry garrison of Ariminum to be replaced by infantry.[15] In this way the cavalry could join with other cavalry forces and use their mobility outside of the city, while the infantry under some obscure commander guarding the city would draw less attention to the city than a strong cavalry force under John. Vitiges sent a large army to retake Mediolanum while he moved to besiege Ariminum himself. Vitiges tried to hinder the Byzantine movement by garrisoning an important tunnel on the road to Ancona. This garrison was defeated, while Vitiges had to maneuver himself around a number of Byzantine garrisons to avoid losing time in fighting useless engagements. Ultimately, the Byzantines were successful in reinforcing Ariminum, however, John refused to leave the city. John managed to prevent the siege tower used by the Goths from reaching the walls which caused Vitiges to withdraw. John wanted to prevent this withdrawal and sallied out but was, like Belisarius at Rome, defeated, which caused Vitiges to keep besieging the now weakened garrison. Needing fewer men, as no assault was to be made, Vitiges sent troops against Ancona and reinforced Auximus. Belisarius could either take Auximus and move on Ariminum with a secure rear, or bypass Auximus to save time. If it took too long to get there, Ariminum might fall. The Byzantines were divided into two groups; one led by Narses who wanted to move on Ariminum immediately, while the other wanted to first take Auximus. A message from John eventually convinced Belisarius to move to Ariminum. During this operation Belisarius would station a part of his forces near Auximus to secure his rear.[13]

The arrival of a Byzantine relief force under Belisarius and Narses compelled the Ostrogoths to give up the siege and retreat to their capital of Ravenna.[13][38] The force had been too small to actually challenge the Goths, but through deception, Belisarius had managed to convince the Goths otherwise. Belisarius had approached from multiple sides including over the sea, which convinced the Goths they faced a huge force.[13] The troops were also ordered by Belisarius to light more campfires than necessary to strengthen the deception.

John made it a point to thank Narses for his rescue instead of Belisarius or Ildiger, the first officer to reach the city. This might have been to insult Belisarius or to avoid being indebted according to the Roman patronage tradition of which some remnants were probably still part of Byzantine culture. John (and Narses) might not have been convinced of Belisarius' competence, as the Vandals and Goths were by then perceived as weak, while he had been relatively unsuccessful against the Persians.

Narses' supporters tried to turn Narses against Belisarius, claiming that a close confidant of the emperor should not take orders from a "mere general".[15] Belisarius, in turn, warned Narses that his followers were underestimating the Goths. He pointed out that their current position was surrounded by Gothic garrisons, and proposed to relieve Mediolanum and besiege Auximus simultaneously. Narses accepted the plan, with the provision that he and his troops would move into the region of Aemilia. This would pin down the Goths at Ravenna, and as such put Belisarius' forces in a secure position, as well as preventing the Goths from reclaiming Aemilia. Narses claimed that if this wasn't done, the rear of the troops besieging Auximus would be open to attack. Belisarius ultimately decided against this, as he was afraid this would spread his troops too thin. He showed a letter from Justinian that said that he had absolute authority in Italy to act "in the best interests of the state" to force Narses into accepting the decision. Narses replied that Belisarius wasn't acting in the best interests of the state.

From the later part of the siege of Rome onwards, reinforcements had arrived in Italy;[15] during the siege of Ariminum, another 5,000 reinforcements landed in Italy, close to the siege where they were needed, clearly by design.[13] The last group of reinforcements was 7,000 strong and led by Narses.[13] After these arrived, the Byzantines had around 20,000 troops in Italy in total.[13] John claimed that about half of the troops were loyal to Narses instead of Belisarius.[13]

Belisarius gave up his original plan and instead of sending forces to besiege Urviventus (Orvieto) and himself besieging Urbinus.[15] Narses refused to share a camp with Belisarius and he and John claimed the city could not be taken by force and abandoned the siege. As Belisarius sent the assault forwards, the garrison surrendered, as the well in the city stopped working. Narses reacted by sending John to take Caesena. While that attack failed miserably, John quickly moved to surprise the garrison at Forocornelius (Imola), and so secured Aemilia for the Byzantines. Shortly after Belisarius' arrival, the Urviventus garrison ran out of supplies and surrendered.

In late December, shortly after the siege of Urbanus and Urviventus, Belisarius sent troops to reinforce Mediolanum.[15] Unsure of the Gothic numbers, they requested aid from John and other troops under Narses. John and the other commanders refused to follow Belisarius' order to assist, stating that Narses was their commander. Narses repeated the order but John fell ill and they paused for him to recover. Meanwhile, the revolt at Mediolanum was bloodily suppressed by the Goths.[39] The desperate garrison had been promised safety in return for abandoning the city, which they subsequently did. As the population had revolted, they were considered traitors and many were slaughtered. Subsequently, the other cities in Liguria surrendered to avoid the same fate. Narses was subsequently recalled.

Finishing the conquest

In 539, Belisarius set up siege forces around Auximum and sent troops to Faesulae,[15][40] starving both cities to submission by late 539.[40] He led the siege of Auximum himself; knowing he couldn't storm the city, he tried to cut the water supply but this failed. When the captured leaders from the Faesulae garrison were paraded in front of the city, its garrison too surrendered. If he moved on Ravenna his rear would now be secure. Vitiges hadn't been able to reinforce these places, as there was a food shortage throughout Italy and he couldn't gather enough supplies for the march. Belisarius stationed his army around the Ostrogothic capital of Ravenna in late 539.[41]

The grain shipment to the city hadn't been able to proceed to the city, so when the Byzantines advanced on Ravenna, the grain was captured. Ravenna was cut off from help on its seaward side by the Byzantine navy patrolling the Adriatic Sea.[41] When Belisarius besieged Ravenna, the Gothic nobles, including Vitiges, had offered the throne of the "western empire" to him. Belisarius feigned acceptance and entered Ravenna via its sole point of entry, a causeway through the marshes, accompanied by a comitatus of bucellarii, his personal household regiment (guards).[41] He also prepared a grain shipment to enter the city when it surrendered. Soon afterward, he proclaimed the capture of Ravenna in the name of the Emperor Justinian.[41] The Goths' offer raised suspicions in Justinian's mind and Belisarius was recalled. He returned home with the Gothic treasure, king and warriors.

Later campaigns

Against Persia

For his next assignment, Belisarius went to the east to fight the Persians.[15] Unlike during the Gothic and Vandalic wars, he wasn't accompanied by his wife. The Byzantines expected that Khosrow, like in the previous year, would move through Mesopotamia, but instead, Khosrow attacked Lazica, where the population was treated poorly by the Byzantines. The Lazicans had invited Khosrow, who concealed his movement by claiming he was going to fight the Huns in the north while instead, the Huns assisted Khosrow. When Belisarius arrived in the east he sent spies to gather information. He was told that the Persians were moving north to fight the Huns. Meanwhile, Belisarius had trained and organized his troops who had been terrified of the Persians before his arrival. He decided he could attack Persia in relative safety. Some of Belisarius' officers protested, as staging an offensive would leave the Lakhmids free to raid the eastern provinces. Belisarius pointed out that the Lakhmids would be filling the next months with religious celebrations and that he would be back within two months.

With the same reasoning he used in Italy for the siege of Auximus and other sieges and the marching column in Africa, he determined that Nisibis had to be taken first to secure his rear if he moved further into Persia.[15] Meanwhile, the war was going poorly for the Byzantines to the north, Lazica was taken and a significant Byzantine garrison changed sides, possibly not having been paid for years.

When Belisarius approached Nisibis he ordered a camp to be set up at a significant distance from the city.[15] His officers protested at this, but he explained to them that this was so that if the Persians sallied out and were defeated, the Byzantines would have more time to inflict casualties during the retreat. At the battle of Rome, during the siege of Rome, Belisarius had been defeated, but much of his army was able to retreat the short distance back to the city, something which he did not want to occur when the roles were reversed. Some of his officers disagreed so vehemently that they left the main force and camped close to the city. Belisarius warned them that the Persians would attack just before the first Byzantine meal, but the officers still sent their men to get food at this time and as a result, were caught in disorder by an attack. Belisarius observed what was going on and was already marching to their aid before messengers requesting aid even arrived. He turned the tide and won the battle. Having defeated the garrison but still not being in a strong enough position to storm the fortifications, he moved past the city. He didn't fear being attacked from the rear by the garrison anymore, mostly because their confidence was broken. While he besieged Sisauranon, he sent troops to raid the rich lands beyond the Tigris. While Belisarius' assaults on the city were repulsed by its 800-strong garrison and suffered heavy losses, the city ran out of supplies and the garrison changed sides. At this point, the troops raiding Persia returned home without informing Belisarius. At this point, up to a third of Belisarius' forces had caught a fever, and the Lakhmids were about to take up arms again. As he did with other major decisions, Belisarius asked his officers' opinions; they concluded they should retreat. Procopius heavily criticized this, claiming that Belisarius could have marched on and taken Ctesiphon. He disregarded the fact that no information on Persian dispositions was available and Belisarius hadn't been able to take Sisauranon by force, making it unlikely he could have stormed Ctesiphon.

In the campaign of 542, Belisarius got the Persians to call off their invasion using trickery.[15] Khosrow had wanted to raid Byzantine territory again but Belisarius moved to the area. When Khosrow sent an ambassador, Belisarius took 6,000 of his best men with him for a meeting. Taking only hunting equipment with them, it seemed like it was a hunting party from a larger equally high-quality force. Fooled by the deception, the Persians, knowing that if they were defeated they would be trapped in Byzantine territory, retreated. Belisarius also sent 1,000 cavalry into the Persian retreat route; if an engagement was fought this might have pointed out Byzantine weakness. During the retreat, Belisarius constantly kept the pressure on, preventing Khosrow from raiding. In return for the Persian withdrawal from imperial lands, the Byzantines sent ambassadors, as the Persian ambassador had requested from Belisarius at their meeting. The meeting had been just a ruse to spy on the Byzantine troops, and as such, when Belisarius took the pressure off, Khosrow attacked some Byzantine towns. Sacking Callinicum, Khosrow could claim success. Some claimed that by not harassing Khosrow, Belisarius had made a serious error, but this view was not brought up in court. Despite Callinicum, Belisarius was acclaimed throughout the East for his success in repelling the Persians.[42] Crucial to the success of Belisarius' deception had been Khosrow's fear of catching the plague if he remained in Byzantine territory for too long, which made maintaining a tactical position in Byzantine territory highly dangerous. By showing his best troops in the open, Belisarius made clear that his army was not weakened by the plague and seemingly not afraid to catch it.

Return to Italy

While Belisarius was in the east, the situation in Italy had vastly deteriorated.[15] The governor sent to the area, a man named Alexander, was corrupt. He trimmed the edges of coins and kept the trimmings of precious metal to increase his own wealth. He charged many soldiers with corruption and demanded they pay fines, and he decreased military spending and demanded that tax withheld from the Goths would be instead paid to the Byzantines.

As a result, many Byzantine soldiers defected or mutinied. The command of the troops in Italy was divided by Justinian to prevent any commander from becoming too powerful. Most of the time these commanders refused to work together as Justinian's plague made it dangerous to leave the base. Meanwhile, the Goths under the brilliant and energetic leadership of Ildibad and Totila went on the offensive and recaptured all of northern Italy and parts of the south. Apparently Totila considered the opportunity to win an easy victory greater than the risk of losing his force due to plague. As a result, they won many engagements against the uncoordinated Byzantines including the Battle of Treviso, the siege of Verona, the Battle of Faventia, the Battle of Mucellium and the siege of Naples. But by now they weren't powerful enough to capture Rome.

In 544, Belisarius was reappointed to hold command in Italy.[15] Before going to Italy, Belisarius had to recruit troops. When he finished his force numbered roughly 4,000 men. Justinian wasn't able to allocate significant resources, as most troops were still needed in the east and the plague had devastated the empire.

During the upcoming campaign, Totila mostly wanted to avoid sieges.[15] The Byzantines had proven themselves adept at sieges, but he had proven multiple times he could defeat them in open battle. Therefore, he razed the walls of towns he took; he wanted neither to be besieged there nor to have to besiege them later. Belisarius, on the other hand, wanted to avoid battle; he had entirely avoided battle after the battle of Rome. With forces as small as his, he wanted to avoid losing too many men and instead avoid the Goths from making progress through other means.

In Italy, many soldiers were mutinous or changed sides, which Belisarius hoped would stop when he was reappointed; it didn't.[15][26] The Byzantine garrison at Dryus were running out of supplies and made plans to surrender, but when Belisarius arrived, he quickly arranged for supplies to be sent by ship. The Goths failed to notice the ships until it was too late and abandoned the siege. Now Belisarius himself sailed to Italy, landing at Pola. Totila quickly heard of this and sent spies pretending to be Byzantine messengers. Belisarius fell for the ruse, so Totila immediately knew the state of his army; he wouldn't be deceived like Khosrow. Belisarius himself didn't remain idle and went to Ravenna to recruit extra troops. While people respected Belisarius, they were smart enough to notice that a fair deal made with Belisarius would be ruined by his often corrupt and incompetent successors. As a result, not a single man enlisted. This also meant that Belisarius' normal strategy of winning over the people through benevolence wouldn't work.

Not wanting to remain idle, Belisarius sent troops into Aemilia.[15] This was successful until the Illyrian troops went home to deal with a Hunnish incursion. The remaining Byzantines successfully ambushed a significant Gothic force, and the incursion ended in a victory. Next, Belisarius sent some men to assist the besieged Auximus, they succeeded but they were defeated while moving back. Still wanting to retain some initiative, Belisarius sent men to rebuild some nearby forts. Belisarius undertook no other operations, so despite winter arriving, Totila started the sieges of some towns, secure from the Byzantine threat.

When requesting reinforcement, Belisarius asked for barbarian horse archers, as he knew the Goths were unable to counter these.[15] Justinian was fighting wars on many fronts and the plague was devastating Constantinople for a second time; he was thus unable to provide even the equipment and money needed to re-equip and pay the forces already in Italy.

Totila was enjoying great success in his recent sieges.[15] Herodian, commander of a garrison, surrendered very quickly to the Goths, having seen the unfavorable treatment Justinian had given Belisarius after his recent Persian campaign. By now the Goths had acquired enough strength to move on Rome. Like Herodian, the commander of the Roman garrison, Bessas, was afraid of poor treatment or even being prosecuted after the siege was lifted. As a result, he remained idle when Belisarius ordered him to assist in the relief of the city. When Belisarius attempted to assist the city with supplies, he came up against a blockade on the Tiber. He overcame this using a siege tower with a boat on top. The boat was filled with burnable materials, so when it was thrown into one of the Gothic towers in the middle of the blockade, the entire garrison died either on impact or because of the fire. Belisarius had left a force under Isaac the Armenian to guard Portus with orders not to leave the city under any circumstances. Now Belisarius heard he had been captured and rushed back to Portus. Isaac had left the city and was captured outside its walls, and the city was safe. With surprise lost, no assistance from Bessas or John, who was blocked off in Calabria, and with little resources, Belisarius wasn't able to prevent Totila from eventually capturing the city. However, it is worth noting a letter that Belisarius wrote to Totila, according to Procopius, reportedly prevented Totila from destroying Rome:

While the creation of beauty in a city which has not been beautiful before could only proceed from men of wisdom who understand the meaning of civilization, the destruction of beauty which already exists would be naturally expected only of men who lack understanding, and who are not ashamed to leave to posterity this token of their character. Now among all the cities under the sun, Rome is agreed to be the greatest and the most noteworthy. For it has not been created by the ability of one man, nor has it attained such greatness and beauty by a power of short duration, but a multitude of monarchs, many companies of the best men, a great lapse of time, and an extraordinary abundance of wealth have availed to bring together in that city all other things that are in the whole world, and skilled workers besides. Thus, little by little, have they built the city, such as you behold it, thereby leaving to future generations memorials of the ability of them all, so that insult to these monuments would properly be considered a great crime against the men of all time; for by such action, the men of former generations are robbed of the memorials of their ability, and future generations of the sight of their works. Such then, is the facts of the case, be well assured of this, that one of two things must necessarily take place: either you will be defeated by the emperor in this struggle, or, should it so fall out, you will triumph over him. Now, in the first place, supposing you are victorious, if you should dismantle Rome, you would not have destroyed the possession of some other man, but your own city, excellent Sir, and, on the other hand, if you preserve it, you will naturally enrich yourself by a possession the fairest of all; but if in the second place, it should perchance fall to your lotto experience the worse fortune, in saving Rome you would be assured of abundant gratitude on the part of the victor, but by destroying the city you will make it certain that no plea for mercy will any longer be left to you, and in addition to this you will have reaped no benefit from the deed. Furthermore, a reputation that corresponds with your conduct will be your portion among all men, and it stands to wait for you according to you decide either way. For the quality of the acts of rulers determines, of necessity, the quality of the repute which they win from their acts.[43]

Meanwhile, Totila had also been very successful in his other efforts.[15] Famine had spread throughout much of Italy and as he did not have to fear Belisarius sending aid to besieged towns, he could take full advantage. Belisarius had spent the winter in Epidamnus and when he sailed back (before attempting to relieve Rome) to Italy, he did so with reinforcements from Justinian. He split his force in two, one part successfully campaigning in Calabria under John nephew of Vitalianus, the other part, under Belisarius' command, tried to lift the siege of Rome but failed. A force sent by Totila prevented John from leaving Calabria. After capturing Rome, Totila sought peace, sending a message to Justinian. He received the reply that Belisarius was in charge of Italy.

Belisarius decided to march on Rome himself after Totila left the area.[15] On the way, however, he marched into an ambush. Despite successfully ambushing Belisarius, the fighting eventually turned in favor of the Byzantines. Belisarius retreated, as it was obvious he wouldn't be able to surprise the city, but later marched on Rome again and took it. Totila marched on the city again but quickly abandoned the siege. Rome remained in Byzantine hands until after Belisarius left.[12]

Following this disappointing campaign, mitigated by Belisarius' success in preventing the total destruction of Rome, in 548–49, Justinian relieved him. In 551, after economic recovery (from the effects of the plague) the eunuch Narses led a large army to bring the campaign to a successful conclusion; Belisarius retired from military affairs. At the Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople (553), Belisarius was one of the Emperor's envoys to Pope Vigilius in their controversy over The Three Chapters. The Patriarch Eutychius, who presided over this council in place of Pope Vigilius, was the son of one of Belisarius' generals.

Last battle

The retirement of Belisarius came to an end in 559, when an army of Kutrigur Bulgars under Khan Zabergan crossed the Danube River to invade Roman territory and approached Constantinople.[15] Zabergan wanted to cross into Asia Minor as it was richer than the often ravaged Balkans. Justinian recalled Belisarius to command the Byzantine army. Belisarius got only 300 heavily armed veterans from the Italian campaign and a host of civilians,[12] including or entirely consisting of 1,000 conscripted refugees fleeing from the Huns,[15] to stop the 7,000 Huns. These were probably retired soldiers living in the region. Belisarius camped close to the Huns and had the civilians dig a trench for protection, and lit many torches to exaggerate their numbers. Determining the path the Hunnish advance would take, he stationed 100 veterans on each side and another 100 to block their advance. In the narrow defile the Huns wouldn't be able to maneuver,[12] exploit their greater numbers. and use their arrow fire effectively.[12]

When 2,000 Huns attacked, Belisarius had his 100 veterans who were blocking the path charge, while the civilians made a lot of noise behind him. This confused the Huns, and when he struck their rear they were pressed together so tightly that they could not draw their bows. The Huns fled in disorder, and Belisarius applied so much pressure to them during the retreat that they didn't even use the Parthian shot to harass their pursuers. After the defeat the Huns fled back over the Danube.[12] In Constantinople Belisarius was once again referred to as a hero.

Later life

In 562, Belisarius stood trial in Constantinople, having been accused of participating in a conspiracy against Justinian. His case was judged by the prefect of Constantinople, named Prokopius, and this may have been his former secretary Procopius of Caesarea. Belisarius was found guilty and imprisoned but not long after, Justinian pardoned him, ordered his release, and restored him to favor at the imperial court, contrary to a later legend that Belisarius had been blinded.[44]

In the first five chapters of his Secret History, Procopius characterizes Belisarius as a cuckolded husband, who was emotionally dependent on his debauched wife, Antonina. According to the historian, Antonina cheated on Belisarius with their adopted son, the young Theodosius. Procopius claims that the love affair was well known in the imperial court and the general was regarded as weak and ridiculous; this view is often considered biased, as Procopius nursed a longstanding hatred of Belisarius and Antonina. Empress Theodora reportedly saved Antonina when Belisarius tried to charge his wife at last.

Belisarius and Justinian, whose partnership had increased the size of the empire by 45 percent, died within a few months of each other in 565.[45] Belisarius owned the estate of Rufinianae on the Asiatic side of the Constantinople suburbs. He may have died there and been buried near one of the two churches in the area, perhaps Saints Peter and Paul.

Assessment

Tactics

During his first Persian campaign, Belisarius was on the winning side once, at Dara.[15] In his first few battles he did not hold overall command and as he was promoted soon after these defeats, his performance was probably positive. At Dara, he won a resounding victory by predicting and influencing enemy movement. When the enemy concentrated and broke through, he moved against their rear and defeated them. At the next battle, at Callinicum, he probably tried to copy his own success at Dara. However, he positioned himself at the low ground and was not able to see it when the enemy concentrated to breakthrough. He had created no reserve at all, so he was not able to plug the gap, despite superior numbers. Belisarius' failure to position himself properly, make a cohesive plan, take advantage of the terrain, and plug the created gap caused a disastrous defeat. Once the Persians had concentrated for a decisive attack, they held numerical superiority at the point of pressure, despite inferior numbers overall.

In Africa, he walked accidentally into the battle of Ad Decimum.[15] His ability to see an opportunity to gain the advantage and to take it contrasts positively with Gelimer's inactivity. As such, Hughes judges his generalship during that battle to be superior.

In Italy, he mostly relied on sieges to defeat the Goths.[15] At this he was so efficient that Totila refused to engage in them until Belisarius was unable to take the initiative due to supply shortages.

Strategies

In Italy, to deal with a changing situation, he made multiple strategies inside the span of a year.[15] Meanwhile, his opponent Vitiges had no coherent strategy after the failure of the siege of Rome.

Belisarius tried to keep his strategic rear secure, besieging, for example, Auximus so he could safely move on Ravenna. When he saw fit, he sometimes did operate with a force in his strategic rear, like at the siege of Ariminum, or when he planned to move on Rome without having taken Naples. In the east, he understood that the Persian garrison of Nisibis would be afraid to give the battle a second time after being defeated in the open earlier. Here too, Belisarius operated with a force in his strategic rear.

He wanted not to split his forces into two small contingents,[12] like Gelimer had been forced to do at Ad Decimum, so when Narses proposed a plan to operate with a secure strategic rear, Belisarius refused it with the reason that he would divide his forces too much.[15]

In Belisarius' campaigns, Brogna sees the overarching theme of the strategic offensive then tactical defense followed by offense.[12] This forced his enemy to attack strong defensive positions, like the walls of Rome, suffering horrendous losses.[12] Belisarius could then finish off the enemy with the main strength of his force, his cavalry,[15][12] which contained horse archers to which the Goths and Vandals had no effective response.[12] Helmuth von Moltke the Elder would come up with the idea to use so-called offensive-defensive campaigns to defend Germany centuries later.[46] In these he would also go on a strategic offensive, take up defensive positions on enemy supply lines, and have the larger Russian and French forces attack his strong position.[46] In both cases, the purpose of this kind of strategy was to defeat larger enemy forces effectively.[12][46] When using such tactics, the higher quality of Byzantine troops, compared to the "barbarians", was exploited to the fullest, as wave after wave of Goths, relying on brute force to win, was defeated.[12]

In his assessment of the commander, Hughes concludes that Belisarius' strategic abilities were unrivaled.[15]

Character

At both Thannuris and Callinicum, he fled before the battle was over.[15] While not improving the battlefield situation, this did prevent his own troops from being destroyed. At the battle of Dara, he refused to duel with a Persian champion, and instead sent a champion of his own.[12] At Rome, however, he fought at the frontline with his soldiers.[12] While he was not willing to take an unnecessary risk in the form of a duel, he wanted, and was able, to inspire his men in combat, and seems not to have lacked bravery.[12]

Procopius' portrayal of Belisarius being weak-willed can often also be explained with a good understanding of politics; taking action against his wife, for example, would not have been appreciated by empress Theodora at all. Just like the weak-mindedness in relation to his wife, the influence his soldiers had on him was probably not enough to convince him to move out of Rome. Instead, it was probably overconfidence on his own part. For the rest of his career, he became a cautious commander, which is in line with the notion that Belisarius knew his limits and tried to act within them.[12] He often moved out with only a small force, with which he would have no control and communication problems.[12] Another example of this is when at the battle of Tricamerum he merely advised John, not taking full command. He recognized John was competent and knew more about the situation, and as such John remained in overall command, winning a great victory.

One of the attributes of Belisarius' campaigns was his benevolence towards soldiers and civilians alike.[15] This caused the local population to support him, which was vital to winning, for example, the battle of Ad Decimum. Many enemy garrisons also changed sides, as they could expect leniency. It also put Gelimer under time constraints, and as such forced him to fight the battle of Tricamerum.

He is also noted for his calmness in danger.[12] At Rome, when a rumor spread that the Goths were already in the city, and his men begged him to flee, he instead sent men to verify whether the claim was true and made clear to the officers that it was his job and his alone to deal with such a situation.[12]

Overall performance

Belisarius is generally held in extremely high regard among historians.[15] This is mostly because of the victories at Dara, Ad Decimum and Tricamarum. Little attention has been paid to his defeats in the east and at the Battle of Rome. Brogna puts him among the best commanders in history,[12] Hughes says of him that he remains behind Alexander the Great and Caesar, but not by much.

Battle record

Legend as a blind beggar

According to a story that gained popularity during the Middle Ages, Justinian is said to have ordered Belisarius' eyes to be put out, and reduced him to the status of a homeless beggar near the Pincian Gate of Rome, condemned to asking passers-by to "give an obolus to Belisarius" (date obolum Belisario), before pardoning him.[47] Most modern scholars believe the story to be apocryphal. Philip Stanhope, a 19th-century British philologist who wrote Life of Belisarius, believed the story to be true, based on his review of the available primary sources.[48]

After the publication of Jean-François Marmontel's novel Bélisaire (1767), this account became a popular subject for progressive painters and their patrons in the later 18th century, who saw parallels between the actions of Justinian and the repression imposed by contemporary rulers. For such subtexts, Marmontel's novel received a public censure by Louis Legrand of the Sorbonne, which contemporary theologians regarded as a model exposition of theological knowledge and clear thinking.[49]

Marmontel and the painters and sculptors depicted Belisarius as a kind of secular saint, sharing the suffering of the downtrodden poor—for example, the bust of Belisarius by the French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Stouf. The most famous of these paintings, by Jacques-Louis David, combines the themes of charity (the alms giver), injustice (Belisarius), and the radical reversal of power (the soldier who recognizes his old commander). Others portray him being helped by the poor after his rejection by the powerful.

In art and popular culture

Belisarius was featured in several works of art before the 20th century. The oldest of them is the historical treatise by his secretary, Procopius. The Anecdota, commonly referred to as the Arcana Historia or Secret History, is an extended attack on Belisarius and Antonina, and on Justinian and Theodora, indicting Belisarius as a love-blind fool and his wife as unfaithful and duplicitous.

In the 20th century Belisarius became featured in a number of works of fiction, including the military science fiction Belisarius series by David Drake and Eric Flint.[50]: 280–281 A writer for Tor.com noted that "science fiction and fantasy are obsessed with retelling the story of Belisarius, when the mainstream world isn't particularly interested."[51]

Other works include:

Belisarius as a character

Sculpture

- Bust of Belisarius by the French baroque sculptor Jean-Baptiste Stouf. The sculpture at the J. Paul Getty Villa depicts the general as blind beggar in a manner that suggests a philosopher or saint.

Painting

- Belisarius: (late 1650s) by Salvator Rosa (1615–1673). Given to Lord Townshend in 1726 by King Friedrich William 1st of Prussia, and hung in the 'Belisarius Chamber' at Raynham Hall, Norfolk. Valued at 10,000 guineas in 1854 (2019 – £1.7m); sold for £273 (2019 – £33,500) in the 'Townshend Heritage Sale' at Christies in 1904 to Sir George Sitwell of Renishaw Hall, where it now hangs.

Drama

- Belasarius: a play by Jakob Bidermann (1607)

- The life and history of Belisarius, who conquered Africa and Italy, with an account of his disgrace, the ingratitude of the Romans, and a parallel between him and a modern hero: a drama by John Oldmixon (1713)

- Belisarius: a drama by William Philips (1724)

Literature

- El ejemplo mayor de la desdicha: a play by Antonio Mira de Amescua (1625)

- Bélisaire: a novel by Jean-François Marmontel (1767)

- Belisarius: A Tragedy: by Margaretta Faugères (1795). Though she wrote it as a play, Faugères "intended [this work] for the closet," i.e., to be read and not performed. Her preface voices complaints about "maledictions" and long-winded rhetoric in popular tragic drama, which she says tend to bore and even outrage a reader, and announces her intent to "substitute concise narrative and plain sense." The drama's plot and character development are secondary to moral conflicts, mainly between vengeance and mercy/pity, respectively associated with pride and humility.

- Beliar: 18th-century poem by Friedrich de la Motte Fouque

- A Struggle for Rome: a historical novel by Felix Dahn (1867)

- Belisarius, 19th-century poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Count Belisarius: a novel by Robert Graves (1938); Ostensibly written from the viewpoint of the eunuch Eugenius, servant to Belisarius' wife, but actually based on Procopius' history, the book portrays Belisarius as a solitary honorable man in a corrupt world, and paints a vivid picture of not only his startling military feats but also the colorful characters and events of his day, such as the savage Hippodrome politics of the Constantinople chariot races, which regularly escalated to open street battles between fans of opposing factions, and the intrigues of the emperor Justinian and the empress Theodora.

- Lest Darkness Fall: a 1939 alternative history novel by L. Sprague de Camp. Belisarius appears first as the Roman opponent of the time traveler Martin Padway who tries to spread modern science and inventions in Gothic Italy. Eventually, Belisarius becomes a general in Padway's army and secures Italy for him.

- The Belisarius series: six books by Eric Flint and David Drake (1998–2006). Science Fiction/Alternative History.

- The character "Bel Riose" in Foundation and Empire by Isaac Asimov is based on Belisarius (1952)

- A Flame in Byzantium: a historical horror fiction novel by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (1987)

- The Last Dying Light (2020) by William Havelock, Book 1 of The Last of the Romans. Told from the perspective of Pharas (Varus) the Herulian, and recounts the chaos of the early-6th-century Roman Empire. Under Justinian's patronage, Belisarius becomes one of the foremost generals of the Roman Army. The Last Dying Light discusses Belisarius' earliest years of generalship, while The Last of the Romans covers each of Belisarius' wars in turn.

- Belisarius: Military Master of the West: Book One: Nika: historical novel by Peter Keating Vanguard Press (2021) – written from the view point of Belisarius as he recounts his life after being discharged from the service of Justinian—it paints a different portrait of the man loyal to his emperor, but under the sway of the two most powerful women, the Empress Theodora and his wife Antonina. This work covers his rise to prominence in the service of Justinian, his initial military campaigns in the East, then dealing with the Nika riot and finally becoming the first Roman to completely defeat the Vandals in North Africa and then capture Sicily.

Opera

- Belisario: tragedia lirica by Gaetano Donizetti, libretto by Salvatore Cammarano after Luigi Marchionni's adaptation of Eduard von Schenl's Belisarius (1820), scenography by Francesco Bagnara, premiered during the Stagione di Carnevale, 4 February 1836, Venezia, Teatro La Fenice.

Music

- Let There Be Nothing: a 2020 album by Power Metal band Judicator following Belisarius' life

Films

- Belisarius was portrayed by Lang Jeffries in the 1968 German movie Kampf um Rom, directed by Robert Siodmak.

- He was portrayed by Elguja Burduli in the 1985 Soviet film Primary Russia.

Gaming

- The Archmagos Belisarius Cawl of Warhammer 40,000 also draws his namesake and inspiration from Belisarius.

- Belisarius appears as the playable main protagonist in the Last Roman campaign DLC for Total War: Attila as well as the Historical Battle of Dara, The player receives missions of historical context. Starting at the beginning of the Vandal Wars, he leads the Roman Expedition to reconquer the West (North Africa, Italy, Gaul, Spain), officially for Justinian, but there's always the option to Declare Independence and turn Belisarius himself the Emperor of the West and what he conquers.

- His name is mentioned, and his "ancient palace"/"sunken city" ruins—below a Mosque in Istanbul—are a playable level in Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb.

- Belisarius is a playable character in the Mobile/PC Game Rise of Kingdoms.

- Belisarius is a general in the game European War 7: Medieval and is in the "Rise of Byzantium" Conquest leading the "Byzantine Expedition" where you start in a war against the Vandals but there is always a chance to declare war on the Byzantines.

See also

- Anastasian War

- Asinarius

- Aspar

- Battle of Taginae

- Byzantine Empire under the Justinian dynasty

- Byzantine Empire under the Leonid dynasty

- Conon (general under Justinian I)

- Constantinianus

- Cyprian (Byzantine commander)

- Aetius (general)

- Liberius (praetorian prefect)

- Military deception

- Stilicho

- Strategikon of Maurice

- Teia

- Theodoric the Great

- Tribonian

- Uraias

- Vacis

- Widin

Notes

- ↑ Compare Lillington-Martin (2009) p. 16

- ↑ The exact date of his birth is unknown. Martindale, John R., ed. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume III, AD 527–641. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-521-20160-8.

- ↑ This is the number given by Procopius, Wars (Internet Medieval Sourcebook.)

- ↑ In The Dark Ages 476–918 A.D., Oman states that the Moors got close to Carthage during the conflict

- ↑ In The Dark Ages 476–918 A.D., Oman states the same but does not specifically mention Procopius

- ↑ Brogna states Justinian’s reluctance was due to his advisers’ pleas

- ↑ In The Dark Ages 476–918 A.D., Oman claims Gelimer was located in Numidia

- ↑ Heather claims he was in Byzacena

- ↑ Heather calls them "three hundred regular cavalries"

- ↑ Heather refers to them as Massagetae

- ↑ Heather mentions part of the fleet going on a "private pillage"

- ↑ Heather mentions these claims but doesn’t mention who spread them

- ↑ Brogna states "a few hundred Huns"

- ↑ [According to Hughes and Brogna] The fight was a Byzantine victory and the Goths were forced to withdraw from the region but the Byzantine commander, Mundus, was killed in the pursuit and his army lost heart and also retreated. [according to Hughes] The Goths then captured the city of Salona

- ↑ According to Brogna it fell on 31 December 535

- ↑ Both Hughes and Brogna agree 600 men entered the city. Brogna claims Belisarius sent men to find another entrance into the city. Hughes claims the entrance was found by an Isaurian studying the building techniques of the ancients and doesn’t mention an intentional effort being made by Belisarius.

- ↑ [The Encyclopædia Britannica claims] that Justinian was unaware of Theodora’s intrigue

References

- ↑ Mass, Michael (June 2013). "Las guerras de Justiniano en Occidente y la idea de restauración". Desperta Ferro (in Spanish). 18: 6–10. ISSN 2171-9276.

- ↑ Sometimes called Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see Cameron, Alan (1988). "Flavius: a Nicety of Protocol". Latomus. 47 (1): 26–33. JSTOR 41540754.

- ↑ Robert Graves, Count Belisarius and Procopius’s Wars, 1938

- ↑ Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A history of the Byzantine state and society. Stanford University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8047-2630-6. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ Barker, John W. (1966). Justinian and the later Roman Empire. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-299-03944-8. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ↑ History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the death of Justinian volume 2, by J. B. Bury p. 56

- ↑ Count Marcellinus and His Chronicle by Brian Croke, p. 75

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). Battles that changed history : an encyclopedia of world conflict (1st ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0.

- ↑ Carey, Brian Todd; Allfree, Joshua B.; Cairns, John (2012). Road to Manzikert: Byzantine and Islamic Warfare, 527–1071. Casemate Publishers. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-84884-916-7.

- ↑ "The Rise of Byzantium". War. Vol. 1. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited. 2009. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4053-4778-5.

- ↑ Evans, James Allan (2003). The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. University of Texas Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-292-70270-7. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 Brogna, Anthony (2015). The Generalship of Belisarius. Hauraki Publishing.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 Heather, P. J. (Peter J.) (2018). Rome resurgent : war and empire in the age of Justinian. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199362745. OCLC 1007044617.