The culture of Bengal defines the cultural heritage of the Bengali people native to eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent, mainly what is today Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal and Tripura, where they form the dominant ethnolinguistic group and the Bengali language is the official and primary language. Bengal has a recorded history of 1,400 years.[1]

The Bengalis are dominant ethnolinguistic group. The Bengal region has been a historical melting point, blending indigenous traditions with cosmopolitan influences from pan-Indian subcontinental empires. Dhaka (Dacca) became the capital of Mughal Bengal (Bengal Subah) and the commercial (financial) capital (1610-1757) of Mughal India. Dhaka is the largest and richest Bengali (Bangali) mega city in the world and also the 3rd largest and richest mega city in (Indian sub continent) after Mumbai (Bombay or MMR) and Delhi (NCR). Dhaka is a Beta (β) Global City (Moderate Economic Centre). As a part of the Bengal Presidency, Bengal also hosted the region's most advanced political and cultural centers during British rule.[1]

Fine arts

Performing arts

Music

Bengal has produced leading figures of Indian classical music, including Alauddin Khan, Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan. Common musical instruments include the sitar, tabla and sarod. The Baul tradition is a unique regional folk heritage. The most prominent practitioner was Lalon Shah. Other folk music forms include Gombhira, Bhatiali and Bhawaiya (Jhumur). Folk music in Bengal is often accompanied by the ektara, a one-stringed instrument. Other instruments include the dotara, dhol, bamboo flute, and tabla. Songs written by Rabindranath Tagore (Rabindra Sangeet) and Kazi Nazrul Islam (Nazrul geeti) are highly popular. Bangladesh is the center of Bangla rock, as well as indie, Sufi rock and fusion folk music.

.jpg.webp) A Bangladeshi rock band

A Bangladeshi rock band Bauls in a village

Bauls in a village

Theatre

Bengali theater traces its roots to Sanskrit drama under the Gupta Empire in the 4th century CE. It includes narrative forms, song and dance forms, supra-personae forms, performance with scroll paintings, puppet theatre and the processional forms like the Jatra.

Dance

Bengal has an extremely rich heritage of dancing dating back to antiquity. It includes classical, folk and martial dance traditions.[2][3] Dances in Bengal includes-

Visual arts

Painting

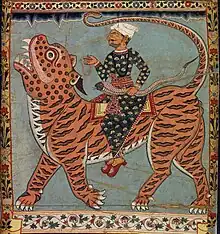

The recorded history of art in Bengal can be traced to the 3rd century BCE, when terracotta sculptures were made in the region. In antiquity, Bengal was a pioneer of painting in Asia under the Pala Empire.

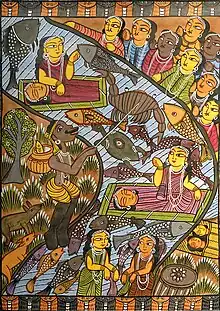

Miniature and scroll painting flourished in Mughal Bengal. Kalighat painting or Kalighat Pat originated in 19th-century Calcutta, in the vicinity of Kalighat Kali Temple of Kolkata, and from being items of souvenir taken by the visitors to the Kali temple, the paintings over a period of time developed as a distinct school of Indian painting. From the depiction of Hindu gods other mythological characters, the Kalighat paintings developed to reflect a variety of themes.

Modern painting emerged in Calcutta with the Bengal school. East Pakistan developed its own contemporary painting tradition under Zainul Abedin. Modern Bangladeshi art has produced many of South Asia's leading painters, including SM Sultan, Mohammad Kibria, Shahabuddin Ahmed, Kanak Chanpa Chakma, Kafil Ahmed, Saifuddin Ahmed, Qayyum Chowdhury, Rashid Choudhury, Quamrul Hassan, Rafiqun Nabi and Syed Jahangir among others.

Architecture

The earliest fortified cities in the region include Wari-Bateshwar, Chandraketugarh and Mahasthangarh. Bengal has a glorious legacy of terracotta architecture from the ancient and medieval periods. The architecture of the Bengal Sultanate saw a distinct style of domed mosques with complex niche pillars that had no minarets. Ivory, pottery and brass were also widely used in Bengali art. The style includes many mosques, temples, palaces, forts, monasteries and caravanserais. Mughal Dhaka was known as the City of Mosques and the Venice of the East. Indo-Saracenic architecture flourished during the British period, particularly among the landed gentry. British Calcutta was known as the City of Palaces. Modernist terracotta architecture in South Asia by architects like Muzharul Islam and Louis Kahn.

Bengali village housing is noted as the origin of the bungalow.

Sculpture

Ancient Bengal was home to the Pala-Sena school of Sculptural Art.[5] Ivory sculptural art flourished across the region under the Nawabs of Bengal. Notable modernist sculptors include Novera Ahmed and Nitun Kundu.

Lifestyle

Textiles

_LACMA_AC1994.131.1.jpg.webp)

Muslin production in Bengal dates back to the 4th century BCE. The region exported the fabric to Ancient Greece and Rome.[5]

Bengali silk was known as Ganges Silk in the 13th century Republic of Venice.[6] Mughal Bengal was a major silk exporter. The Bengali silk industry declined after the growth of Japanese silk production. Rajshahi silk continues to be produced in northern Bangladesh. Murshidabad and Malda are the centers of the silk industry in West Bengal.

After the reopening of European trade with medieval India, Mughal Bengal became the world's foremost muslin exporter in the 17th century. Mughal-era Dhaka was a center of the worldwide muslin trade.

Mughal Bengal's most celebrated artistic tradition was the weaving of Jamdani motifs on fine muslin, which is now classified by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage. Jamdani motifs were similar to Iranian textile art (buta motifs) and Western textile art (paisley). The Jamdani weavers in Dhaka received imperial patronage.[7][8]

Modern Bangladesh is one of the world's largest textile producers, with a large cotton based ready made garments industry.

Clothing

.jpg.webp)

In rural areas, older women wear the shari with hijab while the younger generation wear the selwar kamiz with hijab, both with simple designs. In urban areas, the selwar kamiz and the combination of niqab-burqa-chador is more popular, and has distinct fashionable designs. Traditionally urban Bengali men wore the jama, though costumes such as the panjabi[9] with selwar or pyjama have become more popular within the past three centuries. The popularity of the fotua, a shorter upper garment, is undeniable among Bengalis in casual environments. The lungi and gamcha are a common combination for rural Bengali men. During special occasions, Bengali women commonly wear either sharis, selwar kamizes or abayas, covering their hair with hijab or orna; and men wear a panjabi, also covering their hair with a tupi, toqi, pagri or rumal.

Jama is the long, loose fitting, stitched garment of Bengali Women. Jama was originally worn by Bengali Women in the Mughal court as a symbol of status and wealth. Over time, it has now been more widely adopted by women in other parts of Bengal, including Bangladesh. Jama may also fulfill some interpretations of Islamic rules. Jama is similar to dress.

At Jorashanko (Rabindranath Tagore's home in Kolkata) different drapes of sari were improvised on so that women could step out of the andarmahal (inner house) where they were relegated. This had Tagore's sister-in-law, Jnanadanandini Devi, bringing the Parsi way of draping the sari from Mumbai to Bengal.[10] Chitra Deb, in her book 'Thakurbarir Andarmahal', describes the entire process of how the Parsi sari was adapted into Bengali culture.[11] Before Devi's invention, Bengali women used to wear sari without a blouse underneath and stay in "Andarmahal" to follow "purdah", a concept of modesty bought by Muslims native to Bengal and was followed by both Hindus and Bengali Muslims. Dhakai is another attire of women unique to Bengal. There are several variations of Shari (Bengali Sari) such as Jamdani, Tant, Muslin, Tangail, Kantha, Rajshahi Silk, Dhakai reshom, Baluchari etc. Bengali women also wear Fotua, Bengali Kurti and Kapor which are also unique to Bangladesh. Men wear Gamucha, Panjabi, Lungi, Mujib Coat, Genji and Kaabli which are unique to the men of Bangladesh.

Bengal has produced several of South Asia's leading fashion designers, including Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Bibi Russell, Rukhsana Esrar Runi and Rina Latif.

Cuisine

.jpg.webp)

Rice is the staple food of Bengal. Bhortas (lit-"mashed") are a really common type of food used as an additive too rice. there are several types of Bhortas such as Ilish bhorta shutki bhorta, begoon bhorta and more. Fish and other seafood are also important because Bengal is a reverrine region.

Some fishes like puti (Puntius species) are fermented. Fish curry is prepared with fish alone or in combination with vegetables.Shutki maach is made using the age-old method of preservation where the food item is dried in the sun and air, thus removing the water content. This allows for preservation that can make the fish last for months, even years in Bangladesh.[12]

Bengali pickles are an integral part of Bengali cuisine, adding a burst of flavors to meals. These pickles are made by preserving various fruits, vegetables, and even fish or meat in a mixture of spices, oil, and vinegar or lemon juice, which is why pickles of Bangladesh are unique to the country.

Side Dishes or (Torkari) are commonly eaten with meals in Bengal which are cooked with special Bengali spices. The main dish is almost always served with side dishes. Some typical Bengali dishes are Shorshe Ilish, Macher Jhol, Kala bhuna, Shutki Shira, Bhorta, Chingri Malaikari, Daab Chingri, Katlar kaliya, Dal, Padar jhal, Ilish Pulao, Chingri Pulao, Rui Pulao, Haji biryani, etc. Bengali sweets like Chomchom, Rasmalai, Mishti Doi, Curd of Bogra, Muktagachhar monda, Sandesh, Roshogolla, Chhanamukhi and Pithas are even popular outside of Bangladesh. Pitha and Shemai originally came Bengali Muslim community but most of the other Bengali sweets which are made with chenna are usually invented Hindu and Jain sweets makers of Bengal.

Shutki maach is made using the age-old method of preservation where the food item is dried in the sun and air, thus removing the water content. This allows for preservation that can make the fish last for months, even years in Bangladesh.[13]

Transport

Kolkata is the only city in India to have a tram network. The trams are claimed to slow down other traffic, leading to groups who currently voice abolishing the trams, though the environment-friendliness and the old charm of the trams attract many people.

Kolkata was also the first city in South Asia to have an underground railway system that started operating from 1984. It is considered to have the status of a zonal railway. The metered-cabs are mostly of the brand "Ambassador" manufactured by Hindustan Motors (now out of production). These taxis are painted with yellow colour, symbolising the transport tradition of Kolkata.

Bangladesh has the world's largest number of cycle rickshaws. Its capital city Dhaka is known as the Rickshaw Capital of the World. The country's rickshaws display colorful rickshaw art, with each city and region have their own distinct style. Rickshaw driving provides employment for nearly a million Bangladeshis. Historically, Kolkata has been home to the hand-pulled rickshaw. Attempts to ban its use have largely failed.

There are 150 different types of boats and canoes in Bengal. The region was renowned for shipbuilding in the medieval period, when its shipyards catered to major powers in Eurasia, including the Mughals and Ottomans. The types of timber used in boat making are from local woods Jarul (dipterocarpus turbinatus), sal (shorea robusta), sundari (heritiera fomes) and Burma teak (tectons grandis).

Weddings

.jpg.webp)

Bengali weddings includes many rituals and ceremonies that can span several days. Although Muslim and Hindu marriages have their distinctive religious rituals, there are many common secular rituals.[14][15] The Gaye Holud ceremony is held in Bengali weddings of all faiths.

Cultural institutions, organisations and events

Major organisations responsible for funding and promoting Bengali culture are:

- National Art Gallery (Bangladesh)

- Shilpakala Academy

- Bangladesh Folk Arts and Crafts Foundation

- Ministry of Cultural Affairs (Republic of Bangladesh)

- Ministry of Information & Cultural Affairs (West Bengal)

- List of institutions and organisations

- Chhayanaut

- Bulbul Lalitakala Academy

- Nazrul Institute

- Samdani Art Foundation

- Bangladesh Shishu Academy

- Bangladesh Short Film Forum

- Bishwo Shahitto Kendro

- Bangladeshi Photographers

- Bangladesh National Philatelic Association

- Bangla Academy

- Moviyana Film Society

- Theatre Institute Chattagram

- Bangladesh Film Development Corporation

- Bangladesh Film Archive

- Biswa Bangla

- Paschimbanga Bangla Akademi

- Paschim Banga Natya Akademi

- Bangiya Sahitya Parishad

- Festivals

Both Bangladesh and West Bengal have many festivals and fairs throughout the year.

| Muslim | Hindu | Buddhist | Christian | Secular |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eid al-Fitr | Durga Puja | Buddha Purnima | Christmas | Nababarsha (New Year/ Summer); Wearing colour: |

| Eid al-Adha | Kali Puja | Madhu Purnima | Easter | Basanta Utsab (Spring Festival); Wearing colour: |

| Muharram | Saraswati Puja | Kathin Chibardan | Barsha Mangal (Monsoon salutation); Wearing colour: | |

| Milad un Nabi | Dolyatra (Holi) | Nabanna (Harvest Festival); Wearing colour: | ||

| Shab-e-Barat | Janmashtami | Poush Sangkranti (Winter Festival) | ||

| Laylat al-Qadr | Jagaddhatri Puja |

- Events

Shindur khela in Durga Puja at Kolkata

Shindur khela in Durga Puja at Kolkata Celebration of Pohela Boishakh in Dhaka

Celebration of Pohela Boishakh in Dhaka Bashanto Utsav festival

Bashanto Utsav festival

Pastimes

Cinema

Kolkata and Dhaka are the centers of Bengali cinema. The region's film industry is notable for the history of art films in South Asia, including the works of Academy Award winning director Satyajit Ray and the Cannes Film Festival award-winning director Tareque Masud.

Sports

Traditional Bengali sports consisted of various martial arts and various racing sports, though the British-introduced sports of cricket and football are now most popular amongst Bengalis.

Lathi khela (stick-fighting) was historically a method of duelling as a way to protect or take land and others' possessions. The Zamindars of Bengal would hire lathials (trained stick-fighters) as a form of security and a means to forcefully collect tax from tenants.[16] Nationwide lathi khela competitions used to take place annually in Kushtia up until 1989, though its practice is now diminishing and being restricted to certain festivals and celebrations.[17] Chamdi is a variant of lathi khela popular in North Bengal. Kushti (wrestling) is also another popular fighting sport and it has developed regional forms such as boli khela, which was introduced in 1889 by Zamindar Qadir Bakhsh of Chittagong. A merchant known as Abdul Jabbar Saodagar adapted the sport in 1907 with the intention of cultivating a sport that would prepare Bengalis in fighting against British colonials.[18][19] In 1972, a popular contact team sport called Kabadi was made the national sport of Bangladesh. It is a regulated version of the rural Hadudu sport which had no fixed rules. The Amateur Kabaddi Federation of Bangladesh was formed in 1973.[20] Butthan, a 20th-century Bengali martial arts invented by Grandmaster Mak Yuree, is now practiced in different parts of the world under the International Butthan Federation.[21]

_having_feet_bandaged_at_Celtic_FC%252C_1936_photograph.jpg.webp)

The Nouka Baich is a Bengali boat racing competition which takes place during and after the rainy season when much of the land goes under water. The long canoes were referred to as khel nao (meaning playing boats) and the use of cymbals to accompany the singing was common. Different types of boats are used in different parts of Bengal.[22] Horse racing was patronised most notably by the Dighapatia Rajas in Natore, and their Chalanbeel Horse Races have continued to take place annually for centuries.

.jpg.webp)

The oldest native football clubs of Bengal was Mohun Bagan A.C., which was founded in 1889, and Mohammedan SC, founded in 1891. Mohun Bagan's first major victory was in 1911, when the team defeated an English club known as the Yorkshire Regiment to win the IFA Shield. Since then, more and more clubs emerged in West Bengal, such as Mohun Bagan's main rival SC East Bengal, a team of East Bengali Hindus who had migrated to West Bengal following the 1947 Partition of India. The rivalry also portrayed the societal problems at that time as many of the Mohun Bagan fans were Ghotis who hated the East Bengali immigrants, though Hindu. Mohammed Salim of Calcutta became the first South Asian to play for a European football club in 1936.[31] In his two appearances for Celtic F.C., he played the entire matches barefoot and scored several goals.[32] In 2015, Hamza Choudhury became the first Bengali to play in the Premier League and is predicted to be the first British Asian to play for the England national football team.[33]

Bengalis are very competitive when it comes to board and home games such as Pachisi and its modern counterpart Ludo, as well as Latim, Carrom Board, Chor-Pulish, Kanamachi and Chess. Rani Hamid is one of the most successful chess players in the world, winning championships in Asia and Europe multiple times. Ramnath Biswas was a revolutionary soldier who embarked on three world tours on a bicycle in the 19th century. Shakib Al Hasan, Mushfiqur Rahim, Mashrafe Bin Mortaza, Tamim Iqbal, Soumya Sarkar, Liton Das from Bangladesh and Pankaj Roy, Sourav Ganguly, Manoj Tiwary, Wriddhiman Saha, Mohammed Shami from West Bengal are internationally known cricketers .[34] Local games include sports such as Kho Kho and Kabaddi, the latter being the national sport of Bangladesh.

Media

Bangladesh's Prothom Alo is the largest circulated Bengali newspaper in the world. It is followed by Ananda Bazar Patrika, which has the largest circulation for a single-edition, regional language newspaper in India. Other prominent Bengali newspapers include the Ittefaq, Jugantor, Samakal, Janakantha and Bartaman. Major English-language newspapers in Bangladesh include The Daily Star, New Age, and the weekly Holiday. The Statesman, published from Kolkata, is the region's oldest English-language publication.

Literature

Bengal has one of the most developed literary traditions in Asia. A descent of ancient Sanskrit and Magadhi Prakrit, the Bengali language evolved circa 1000–1200 CE under the Pala Empire and the Sena dynasty. It became an official court language of the Sultanate of Bengal and absorbed influences from Arabic and Persian. Middle Bengali developed secular literature in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was also spoken in Arakan. The Bengali Renaissance in Calcutta developed the modern standardized form of the language in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rabindranath Tagore became the first Bengali writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, and was also the first non-European Nobel laureate. Kazi Nazrul Islam became known as the Rebel Poet of British India. After the partition of Bengal, a distinct literary culture developed in East Bengal, which later became East Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Kazi Nazrul Islam (Bidrohi Kabi; 'the rebel poet')

Kazi Nazrul Islam (Bidrohi Kabi; 'the rebel poet') Rabindranath Tagore (Biswa Kabi; 'the poet of world')

Rabindranath Tagore (Biswa Kabi; 'the poet of world') Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar (Father of modern Bengali alphabets and modern Bengali Prose)

Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar (Father of modern Bengali alphabets and modern Bengali Prose) Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (Sahityo Samrat; 'the emperor of literature')

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (Sahityo Samrat; 'the emperor of literature').jpg.webp) Jasimuddin (Polli Kabi; 'the rural poet')

Jasimuddin (Polli Kabi; 'the rural poet')

Philosophy

The works of ancient philosophers from Bengal have been preserved at libraries in Tibet, China and Central Asia. These include the works of Atisa and Tilopa.[35] Medieval Hindu philosophy featured the works of Chaitanya.

Sufi philosophy was highly influential in Islamic Bengal. Prominent Sufi practitioners were disciples of Jalaluddin Rumi, Abdul-Qadir Gilani and Moinuddin Chishti. One of the most revered Sufi saints of Bengal is Shah Jalal.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Minahan, James B. (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598846607.

- ↑ Hasan, Sheikh Mehedi (2012). "Dance". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ↑ Ahmed, Wakil (2012). "Folk Dances". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ↑ "Folk Dances - Banglapedia". Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- 1 2 Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2015). World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence. Routledge. ISBN 9781317451679.

- ↑ Van Schendel, Willem (2012). "Silk". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed). Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ "In Search of Bangladeshi Islamic Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ "The panjabi story". 14 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ↑ "Have you heard of Rabindra Vastra? | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. 13 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Deba, Citrā (2006). Ṭhākurabārira andaramahala (3. paribardita o parimārjita saṃskaraṇa ed.). Kalakātā: Ānanda. ISBN 8177565966. OCLC 225391789.

- ↑ Food Product - Banglapedia https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Food_Product Archived 2 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "The shutki trade in Bangladesh". 15 February 2023. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ "Bengali Wedding Rituals – A Traditional Bengali Marriage Ceremony". about.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ↑ "Weddings In India – Wedding in Exotic Indian Locations". www.weddingsinindia.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ↑ ঈদ উৎসবের নানা রং Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine,সাইমন জাকারিয়া, দৈনিক প্রথম আলো। ঢাকা থেকে প্রকাশের তারিখ: আগস্ট ০২, ২০১৩

- ↑ "Lathi Khela to celebrate Tangail Free Day". dhakamirror.com. 13 December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Zaman, Jaki (10 May 2013). "Jabbarer Boli Khela: Better Than WWE". The Independent. Dhaka. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ "Jabbarer Boli Khela tomorrow". The Daily Star. 24 April 2013. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ Faroqi, Gofran (2012). "Kabadi". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "Seminar on Butthan Combat Sports & Co-competition system held". United News of Bangladesh. 13 October 2019. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ S M Mahfuzur Rahman (2012). "Boat Race". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ↑ "Bangladeshi Player Shakib Al Hasan named best all-rounder in all formats by ICC: Some interesting facts about the cricketer". India Today. New Delhi, India. 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "Why Shakib Al Hasan is one of cricket's greatest allrounders". ESPNcricinfo. 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "Where does Shakib rank among the greatest all-rounders?". The Business Standard. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ Cricfrenzy.com, Z. Ahmed (1 August 2020). ""I don't play to be the best all-rounder of all time": Shakib Al Hasan". cricfrenzy.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "Why Shakib Al Hasan is one of cricket's greatest allrounders". ESPN. 24 March 2020. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ Parida, Bastab K. (5 July 2019). "Greatest all-rounder of 21st century debate – where does Shakib Al Hasan stand?". SportsCafe.in. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "Best All-Rounders in Cricket History". TheTopTens. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "Is Shakib Al Hasan a greater allrounder than Garry Sobers?". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ↑ Breck, A. Alan Breck's Book of Scottish Football. Scottish Daily Express, 1937, cited in "Salim, Mohammed". All time A to Z of Celtic players. thecelticwiki.org. 29 May 2006. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013. See also, "Barefooted Indian who left Calcutta to join Celtic". The Scotsman. 12 December 2008. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Scottish Daily Express, 29 August 1936, cited in Majumdar, B. and Bandyopadhyay, K. A Social History Of Indian Football: Striving To Score Archived 18 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge, 2006, p. 68.

- ↑ Trehan, Dev (2 September 2019). "Hamza Choudhury can be first British South Asian to play for England, says Michael Chopra". Sky Sports. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ Prabhakaran, Shaji (18 January 2003). "Football in India – A Fact File". LongLiveSoccer.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ Islam, Aminul (2012). "Philosophy". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.