| Great Bengal Famine of 1770 | |

|---|---|

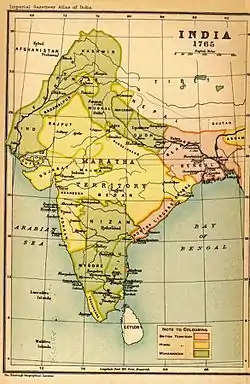

India in 1765, showing the major towns in Bengal and the years in which they had been annexed by the British | |

| Country | British India (Company Rule) |

| Location | Bengal |

| Period | 1769–1771 |

| Total deaths | Between seven and 10 million in conventional estimates |

| Causes | Policy failure and drought |

| Relief | Attempts to stop exportation and hoarding or monopolising grain; 15,000 expended in importation of grains. |

| Effect on demographics | Population of Bengal declined by around a third |

| Consequences | East India Company took over full administration of Bengal |

The Great Bengal famine of 1770 was a famine that struck Bengal and Bihar between 1769 and 1770 and affected some 30 million people.[1] It occurred during a period of dual governance in Bengal. This existed after the East India Company had been granted the diwani, or the right to collect revenue, in Bengal by the Mughal emperor in Delhi,[2][3] but before it had wrested the nizamat, or control of civil administration, which continued to lie with the Mughal governor, the Nawab of Bengal Nazm ud Daula (1765-72).[4]

Crop failure in autumn 1768 and summer 1769 and an accompanying smallpox epidemic were thought to be the manifest reasons for the famine.[5][1][6][7] The East India Company had farmed out tax collection on account of a shortage of trained administrators, and the prevailing uncertainty may have worsened the famine's impact.[8] Other factors adding to the pressure were: grain merchants ceased offering grain advances to peasants, but the market mechanism for exporting the merchants' grain to other regions remained in place; the East India Company purchased a large portion of rice for its army; and the Company's private servants and their Indian Gomasthas created local monopolies of grain.[5] By the end of 1769 rice prices had risen two-fold, and in 1770 they rose a further three-fold.[9] In Bihar, the continual passage of armies in the already drought-stricken countryside worsened the conditions.[10] The East India Company provided little mitigation through direct relief efforts;[11] nor did it reduce taxes, though its options to do so may have been limited.[12]

By the summer of 1770, people were dying everywhere. Although the monsoon immediately after did bring plentiful rains, it also brought diseases to which many among the enfeebled fell victim. For several years thereafter piracy increased on the Hooghly river delta. Deserted and overgrown villages were a common sight.[13][14] Depopulation, however, was uneven, affecting north Bengal and Bihar severely, central Bengal moderately, and eastern only slightly.[15] The recovery was also quicker in the well-watered Bengal delta in the east.[16]

Between seven and ten million people—or between a quarter and third of the presidency's population—were thought to have died.[11][17][5][1][18][19][20] The loss to cultivation was estimated to be a third of the total cultivation.[21][22] Some scholars consider these numbers to be exaggerated in large part because reliable demographic information had been lacking in 1770.[23][24] Even so, the famine devastated traditional ways of life in the affected regions.[25][26] It proved disastrous to the mulberries and cotton grown in Bengal; as a result, a large proportion of the dead were spinners and weavers who had no reserves of food.[27][28] The famine hastened the end of dual governance in Bengal, the Company becoming the sole administrator soon after.[29] Its cultural impact was felt long afterwards, becoming the subject a century later of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee's influential novel Anandamath.[11][17]

Name and geography

The Bengali name Chiẏāttôrer mônnôntôr is derived from Bengali calendar year 1176 and the Bengali word meaning famine.[lower-alpha 1]

The regions in which the famine occurred affected the modern Indian states of Bihar and West Bengal in particular, but the famine also extended into Orissa and Jharkhand as well as modern Bangladesh. Among the worst affected areas were Central and Northern Bengal, and Tirhut, Champaran and Bettiah in Bihar.[30] South-East Bengal escaped unscathed — it had an excess production in the famine years.[30]

Background

The famine occurred in Bengal, then ruled by the East India Company. Their territory included modern West Bengal, Bangladesh, and parts of Assam, Odisha, Bihar, and Jharkhand. It was earlier a province of the Mughal empire from the 16th century and was ruled by a nawab, or governor. In early 18th century, as the Mughal empire started collapsing, the nawab became effectively independent of the Mughal rule.

In the 17th century, the English East India Company was granted the town of Calcutta by the Mughal Prince Shah Shuja. During the following century, the company obtained sole trading rights for the province and became the dominant power in Bengal. In 1757, at the Battle of Plassey, the East India Company defeated the nawab Siraj Ud Daulah, annexing large portions of Bengal afterwards. In 1764 their military control was reaffirmed at Buxar. The subsequent treaty gave them taxation rights, known as dewan; the East India Company thereby became the de facto ruler of Bengal. In addition to profits from trade, the Company had been granted rights of taxation in 1764 and within a few years, had raised land revenue collections by about 30%.[31]

Pre-famine distress

The famine came in the backdrop of a multitude of subsistence crises that had affected Bengal since the early eighteenth century.[32]

A failure of monsoon in Bengal and Bihar had led to partial shortfall of produce in 1768; market prices were higher than usual in early 1769.[33][34] With usual rains in 1769, the situation eased for a while and grains were even exported to Madras Presidency.[34] By late September, the situation was again bleak with drought-like-conditions on the horizon.[33]

Famine and policies

.jpg.webp)

On 18 September 1769, Naib Nazim of Dhaka Mohammed Reza Khan informed Harry Verelst, President of the Council at Fort William about the "dryness of the season".[35] The same month, John Cartier, Esquire (and Second-in-Command) of the Council chose to inform the Court of Directors in London about impending famine-like conditions in Bengal — a century later, W. W. Hunter would note this letter to be the "only serious intimation" about the approaching famine, and find the absence of President Verelst's affirmation to be striking.[33][34] Other letters sent in the same month to the Board speculate about potential loss in revenue collection but do not discuss the famine.[34][lower-alpha 2]

On 23 October, Becher had reported to the Council about "great dearth and scarcity" of food grains at Murshidabad.[35] This prodded the council to purchase 1.2 million maunds of rice for its army, as an emergency measure.[35] Charles Grant, Betcher's agent noted that the first sign of the famine was already visible in northern districts of Bengal by November.[35] By late December, food prices had spiked sharply and the western districts of Bengal along with Bihar were also in a precarious condition.[35]

On 7 December, Reza Khan and Shitab Rai proposed to the Council that they enforce a humane grain collection scheme for the upcoming fiscal year, in proportion to the individual produce of peasants.[35] The proposal was not replied to; W. W. Hunter would later accuse that these people often had their incentives to dramatize general distress.[35] On 25 January 1770, Cartier proposed to the Board that land taxes be remitted by about seven percent in afflicted areas on grounds of widespread suffering.[33][34] Ten days later, Cartier reversed his stance noting that the revenues kept on being paid despite significant distress.[33] On 28 February, the Council proposed that husbandmen who failed to pay the taxes be treated with leniency due to overbearing conditions of a poor harvest.[34] Overall, no relief plan was yet designed by February.[35] Despite initial hopes of a reversal in fortunes, there were no rains and the spring harvest was scanty; acting upon the advice of Reza Khan, the Council chose to increase taxes by 10% to meet revenue targets.[33][34][35] Grain prices had kept rising across the year.[35]

By middle of May, the distress had exploded into a full-blown famine marked with mass-starvation, beggary, and death.[36][33][34] The prices of food would skyrocket, as the province ran out of money to pay for the scarce produces and trade effectively ceased.[33] Khan noted that lakhs of people were dying daily, fires were widespread, and the tanks had not a drop of water.[35] These conditions would continue for about three months.[33]

Mitigation

The Company provided little meaningful mitigation — there was no reduction in taxation or any significant relief effort.[33][38]

In October 1769, the Company requested that storehouses be constructed in Patna and Murshidabad; city officials were instructed to prevent monopoly of trade and have farmers raise "every sort" of dry grain, that was possible. The orders were largely unsuccessful; many Company officials along with their Indian assistants (Gomasthas) would exploit the famine to create grain-monopolies.[33]

On 13 February, Khan and Becher proposed that six rice-distribution centers be opened in Murshidabad to provide half a seer of rice a day per head.[35] The proposal was approved and the Council borne about 46% of the expenditure, the remaining sum were paid by Nawab Najabat Ali, Khan himself, Rai Durlabh, and Jagat Seth.[35] One distribution center was opened by Reza Khan at his palace of Nishat Bagh.[35] The Murshidabad model was later emulated in Calcutta and Burdwan to feed about 3000 men every day — at a daily expenditure of about 75 rupees — since early April.[35] Rice were also charitably distributed at Purnea, Bhagalpur, Birbhum, Hugli and Jesore.[35] Overall, about 4000 pounds of rice was arranged by the Company over six months.[33]

Those in the employment of Company and Nizamat were especially favored.[35] Becher obtained a total of 55,449 maunds of rice from Barisal, which was dispatched for Company troops and their dependents across Bengal.[35][lower-alpha 3]

Districts which exceeded a death-toll of twenty thousand per month were granted packages of 150 Rupees.[33] Export-import embargoes were set up to check prices but they only contributed to worsening the situation — the province had no money to pay for the scarce produces and trade effectively ceased.[33]

Death, migration, and depopulation

Contemporary estimates

In May 1770, the Court of Directors estimated that about one-third of the population (approx. ten million) had perished.[38] The estimates were then revised by Becher on 2 June to about three in every eight people.[33] On 12 July, Becher claimed that 500 people were dying in Murshidabad everyday and the condition was far worse in the rural hinterlands; cannibalism was apparently on exhibition.[35]

Malaria and cholera remained additional factors.[38] A smallpox epidemic that coincided with the start of the pandemic was particularly severe and included Nawab Najabat Ali Khan of Murshidabad among the victims.[33][38]

Modern scholarship

These figures have been uncritically reproduced by most modern scholars.[38] Rajat Dutta, in a revisionist history of the economy of Bengal Province, claimed these figures to be "inflated" and carry "little conviction"; a revised toll of 1.2 million dead (~ 4-5% of the population) was put forward.[39] Tim Dyson supports Dutta's claims of inflation, and notes the "popular" figure of ten million, indicative of at-least a 500% increase in annual death rate, to be "barely credible".[38] However, Dyson refrains from making any specific estimate.[38] Highlighted are the facts that contemporary Bengal lacked any significant demographic data outside Calcutta, the few reliable reports on effects of the famine were based on unrepresentative populations, and many cultivators were mobile settlers who simply migrated to better-off territories.[38]

Aftermath

The 1770 monsoons brought some marginal relief, and a perspective on the rampant depopulation — a letter by the Council regretted the wiping out of numerous "industrious peasants and manufacturers".[33] The following year, as the drought receded, most of the land lacked tillers.[33]

Legacy

The economic and cultural impact of the famine was felt long afterwards, becoming the subject a century later of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee's influential novel Anandamath.[11][17]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Chiāttôr' – '76'; '-er' – 'of'; 'mônnôntôr' – 'famine'.

- ↑ In December, Verelst retired from the Council without noting anything about a famine, which was already in process.[34] Cartier was handed over the charges.[34]

- ↑ A net profit of 67, 595 Rupees was incurred. This was adjusted toward net distribution costs.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Visaria & Visaria 1983, p. 528.

- ↑ Brown 1994, p. 46.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 30.

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 56.

- 1 2 3 Bhattacharya & Chaudhuri 1983, p. 299.

- ↑ Roy, Tirthankar (2019), How British Rule Changed India's Economy: The Paradox of the Raj, Springer, pp. 117–, ISBN 978-3-030-17708-9,

The 1769-1770 famine in Bengal followed two years of erratic rainfall worsened by a smallpox epidemic.

- ↑ McLane, John R. (2002), Land and Local Kingship in Eighteenth-Century Bengal, Cambridge University Press, pp. 195–, ISBN 978-0-521-52654-8,

Although the rains were lighter than normal in late 1768, the tragedy for many families in eastern Bihar, north-western and central Bengal, and the normally drier sections of far-western Bengal began when the summer rains of 1769 failed entirely through much of that area. The result was that the aman crop, which is harvested in November, December, and January, and provided roughly 70 percent of Bengal's rice, was negligible. Rains in February 1770 induced many cultivators to plough but the following dry spell withered the crops. The monsoon of June 1770 was good. However, by this time food supplies had long been exhausted and heavy mortality continued at least until the aus harvest in September.

- ↑ Roy 2021, pp. 88–: "The state mishandled the famine. No state in these times had the infrastructure or the access to information needed to deal with a natural disaster on such a scale. On top of that problem, this was not a normal state. The Company was in charge of taxation, whereas the Nawab looked after governance. The two partners did not trust one another."

- ↑ Roy 2021, pp. 87– "Towards the end of 1769, rice prices had doubled over the previous year, and in 1770, prices were on average six times what they had been in 1768."

- ↑ Roy 2021, pp. 87–: "The 1770 famine owed to a combination of harvest failures and the diversion of food for the troops. Western Bengal and drier regions suffered more. Recovery was quicker in the more water-rich eastern Bengal delta. In the winter of 1768, rains were scantier than usual in Bengal. The monsoon of 1769 started well but stopped abruptly and so thoroughly that the main autumn rice crop was scorched. The winter rains failed again. In the Bihar countryside, the repeated passage of armies through villages already short of food worsened the effects of harvest failure."

- 1 2 3 4 Peers 2006, p. 47.

- ↑ Roy 2021, pp. 88–: "The situation meant that those who had the money did not have local intelligence. The standard custom was a tax holiday for the secondary landlord, expecting the benefit would be passed on to the primary landlord and onwards to the affected peasants. However, the Company neither knew nor commanded the secondary landlords' loyalty and distrusted the Nawab's officers' information on what was going on. Consequently, there was resistance to using this option, yet no other instruments were available to the Company to deal with the famine."

- ↑ Roy 2021, pp. =87–88 "Through the summer months of 1770, death was everywhere. The rains were heavy in the monsoon of 1770, but that brought little cheer among survivors. Emaciated and without shelter from the rains, roving groups and families fell victim to the infections common during and after the rains. Large areas depopulated due to death, disease, and desertion. For several years after the famine, deserted villages, and villages engulfed in forests, were a common sight, and piracy and robbery in the Hooghly river delta became more frequent."

- ↑ Marshall, P. J. (2006), Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828, Cambridge University Press, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6,

In 1769 the rains failed over most of Bihar and Bengal. By the early months of 1770 mortality in western Bengal was very high. People died of starvation or in a debilitated state were mowed down by diseases which spread especially where the starving congregated to be fed.

- ↑ Irschick, Eugene F. (2018), A History of the New India: Past and Present, Routledge, pp. 73–, ISBN 978-1-317-43617-1,

Our evidence, however, indicates that depopulation was most severe in north Bengal and in Bihar, moderately severe in central Bengal, and slight in southwest and eastern Bengal.

- ↑ Roy 2021, pp. 87–: "Recovery was quicker in the more water-rich eastern Bengal delta."

- 1 2 3 Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 78.

- ↑ Grove, Richard; Adamson, George (2017), El Niño in World History, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 81–, ISBN 978-1-137-45740-0,

it is not until 1776 that we start to have access to long runs of instrumental data for El Niño events in South Asia. Just prior to this, in 1766–1771, India, and particularly north-eastern India, experienced droughts that led to a mortality of up to 10 million people. Partial crop failure in Bengal and Bihar was experienced in 1768, while by September 1769 'the fields of rice [became] like fields of dried straw'. In Purnia, in Bihar, the district supervisor estimated that the famine of 1770 killed half the population of the district; many of the surviving peasants migrated to Nepal (where the state was less confiscatory than the East India Company). More than a third of the entire population of Bengal died between 1769 and 1770, while the loss in cultivation was estimated as 'closer to one-half'. Charles Blair, writing in 1874, estimated that the episode affected up to 30 million people in a 130,000 square mile region of the Indo-Gangetic plain and killed up to 10 million, perhaps the most serious economic blow to any region of India since the events of 1628–1631 in Gujarat.

- ↑ Damodaran, Vinita (2014), "The East India Company, Famine and Ecological Conditions in Eighteenth-Century Bengal", in V. Damodaran; A. Winterbottom; A. Lester (eds.), The East India Company and the Natural World, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 80–101, 89, ISBN 978-1-137-42727-4,

Before the end of May 1770, one third of the population was calculated to have disappeared, in June the deaths were returned as six out of sixteen of the whole population, and it was estimated that 'one half of the cultivators and payers of revenue will perish with hunger'. During the rains (July–October) the depopulation became so evident that the government wrote to the court of directors in alarm about the number of 'industrious peasants and manufacturers destroyed by the famine'. It was not till cultivation commenced for the following year 1771 that the practical consequences began to be felt. It was then discovered that the remnant of the population would not suffice to till the land. The areas affected by the famine continued to fall and were put out of tillage. Warren Hastings' account, written in 1772, also stated the loss as one third of the inhabitants and this figure has often been cited by subsequent historians. The failure of a single crop, following a year of scarcity, had wiped out an estimated 10 million human beings according to some accounts. The monsoon was on time in the next few years but the economy of Bengal had been drastically transformed, as the records of the next thirty years attest.

- ↑ Sen, Amartya (1983), Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford University Press, pp. 39–, ISBN 978-0-19-103743-6,

Starvation is a normal feature in many parts of the world, but this phenomenon of 'regular' starvation has to be distinguished from violent outbursts of famines. It isn't just regular starvation that one sees ... in 1770 in India, when the best estimates point to ten million deaths.

- ↑ Bhattacharya & Chaudhuri 1983, pp. 299–300.

- ↑ Marshall, P. J. (2006), Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828, Cambridge University Press, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6,

The proportion of the population who perished can never be known. One-third of the inhabitants of Bengal were sometimes said to have died. Other conjectures were one-fifth.

- ↑ Dyson 2018, pp. 80–81: "However, in assessing the likely scale of the mortality ... there were no demographic data for any significant part of Bengal. Indeed, many Company administrators seldom ventured from Calcutta. The few local reports on famine deaths were for small and unrepresentative populations. Also, as we noted in Chapter 4, cultivators could be very mobile, and they often abandoned their villages at times of famine. Much of any 'depopulation' was undoubtedly caused by out-migration. In addition, birth rates tend to fall during famines, and this too would have reduced the population ... To sum up, the 1769–70 famine was certainly exceptional in terms of Bengal's experience during the eighteenth century (although crop losses from a cyclone and a shift in a river course also contributed to many famine deaths in 1787–88). It is very unlikely, however, that the 1769–70 crisis involved the deaths of 10 million people. Indeed, on Datta's assessment, even a figure of 5 million may well lie outside the plausible range. However, famine mortality and large-scale out-migration did cause significant depopulation in large parts of Bengal—from which it evidently took several years to recover. As late as 1773, Company officials regarded the revival of the province's economy as requiring substantial return-migration from adjacent territories—including the, then, independent state of Awadh."

- ↑ Irschick, Eugene F. (2018), A History of the New India: Past and Present, Routledge, pp. 73–, ISBN 978-1-317-43617-1,

In addition, deaths among the cultivating population were much lower than previous figures, which suggested a loss of one third of the population. Famine mortality in the Burdwan zamindari in central Bengal was not severe and agriculturists who left came back or were replaced.

- ↑ Roy, Tirthankar (2013), An Economic History of Early Modern India, Routledge, pp. 60–, ISBN 978-1-135-04787-0,

The devastation that this episode caused, even if we discount the exaggerated mortality figures produced by contemporaries, owed not so much to the scale of one harvest failure as repeated harvest failures over a succession of seasons. The crop failed over four consecutive harvest seasons in 1769 and 1770. As it became clear in the subsequent history of Indian famines, sustained shortages caused disproportionately large damage to life. It threw traditional modes of insurance out of gear because of depletion of stocks and seeds. It increased vulnerability to epidemic disease because of acute malnutrition.

- ↑ Marshall, P. J. (2006), Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828, Cambridge University Press, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6,

What seems to be certain is that the core areas of western and central Bengal were devastated: these included the districts of Murshidabad, Rajshahi, Birbhum, Hooghly, Nadia and parts of Burdwan.

- ↑ Datta, Rajat (2019), "Subsistence crises and economic history: A study of eighteenth-century Bengal", in Ayesha Mukherjee (ed.), A Cultural History of Famine: Food Security and the Environment in India and Britain, Routledge, pp. 48–, ISBN 978-1-315-31651-2,

One of the most harvest- and price-sensitive social groups in rural Bengal was the textile producer. Famine and dearth impacted upon them by hitting directly at their access to markets for their consumption requirements. The evidence from Malda and Purnea suggests that between half and one-third of those who died in the famine were spinners and weavers. The disruption caused by the drought to mulberries and cotton in 1769 and 1770 meant that those who reared silk-worms (chassars) and those who grew cotton (kappas) in these places were immediately affected. The cultivation of mulberries was an expensive enterprise: "under the most favourable circumstance mulberry will cost the Husbandman five or six, and often from ten to fifteen rupees per bigha", whereas the cultivation cost of rice was "not above one, two or at best three rupees a bigha" (WBSA, CCRM, vol. 6, 19 November 1771). This meant that once peasants entered this sector their survival depended on conducive precipitation and favourable food prices. The situation in 1769–70 was precisely the opposite on both counts, and therefore proved disastrous for such producers. There was an "incredible mortality" among the chassars of Rajshahi during the famine (ibid.: vol. 6, 11 November 1771). This was for two reasons. First, the high costs involved in the culture of silk-cocoons meant that the chassars had no reserves to buy food at famine-point prices. Second, the chassars belonged to "only two casts [sic] of the Gentoos [Hindus]" who followed this vocation as a specialized occupation (ibid.). (ibid.). For these reasons, they were perhaps the most harvest-sensitive of all the affected social strata and, not having enough food reserves to fall back upon, they died in large numbers.

- ↑ Marshall, P. J. (2006), Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828, Cambridge University Press, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6,

One indication of the scale of mortality in the worst areas is an estimate that one-third of those who raised silk worms in the famous silk area around Murshidabad were dead. The low-lying delta areas, even in the west, suffered rather less. Everywhere the most vulnerable seem to have been 'the workmen, manufacturers and people employed in the river, who were without the same means of laying by stores of grain as the husbandmen'.

- ↑ Grove, Richard; Adamson, George (2017), El Niño in World History, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 82–, ISBN 978-1-137-45740-0,

The 1768-1770 droughts and famines were a profound blow not only to the system of revenue but to the whole rationale of empire. As such they provided the impetus for the evolution of a famine policy. The immediate devastating circumstances formed part of the impetus for the removal of the 'dual system' of rule in Bengal, whereby the British East India Company had governed together with the Nawab of Bengal. This placed responsibility for the security, administration and economy of Bengal squarely on the Company's shoulders. In removing the dual system, the administrative overhaul of Bengal paved the way for the establishment of the British-run, district-level administration which would continue throughout British rule in India.

- 1 2 Datta, Rajat (2000). Society, economy, and the market : commercialization in rural Bengal, c. 1760-1800. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 249. ISBN 81-7304-341-8. OCLC 44927255.

- ↑ Datta, Rajat (2000). Society, economy, and the market : commercialization in rural Bengal, c. 1760-1800. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors. pp. 333–340. ISBN 81-7304-341-8. OCLC 44927255.

- ↑ Dutta 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Damodaran 2015, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hunter 1871, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Khan 1969.

- ↑ Datta, Rajat (2000). Society, economy, and the market: Commercialization in rural Bengal, c. 1760-1800. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors. pp. 257–259. ISBN 8173043418.

- ↑ Morris, Jan (2005), Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj, Oxford University Press, pp. 120–, ISBN 978-0-19-280596-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dyson 2018.

- ↑ Datta, Rajat (2000). Society, economy, and the market : commercialization in rural Bengal, c. 1760-1800. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors. pp. 262, 266. ISBN 81-7304-341-8. OCLC 44927255.

References

- Bhattacharya, S.; Chaudhuri, B. (1983), "Regional Economy (1757–1857): Eastern India", in Dharma Kumar (ed.), The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 2, C.1757-c.1970, Cambridge University Press, pp. 270–331, doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521228022.008, ISBN 978-0-521-22802-2

- Bowen, H.V (2002), Revenue and Reform: The Indian Problem in British Politics 1757–1773, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-89081-6

- Brown, Judith Margaret (1994), Modern India: the origins of an Asian democracy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-873112-2

- Kumkum Chatterjee, Merchants, Politics and Society in Early Modern India: Bihar: 1733–1820, Brill, 1996, ISBN 90-04-10303-1

- Sushil Chaudhury, From Prosperity to Decline: Eighteenth Century Bengal, Manohar Publishers and Distributors, 1999, ISBN 978-81-7304-297-3

- Hunter, William Wilson (1871). The Annals of Rural Bengal (Fourth ed.). London: Smith, Elder, and Co.

- John R. McLane, Land and Local Kingship in 18th century Bengal, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-52654-X

- Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A concise history of modern India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9

- Peers, Douglas M. (2006), India under colonial rule: 1700–1885, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3

- Visaria, Leela; Visaria, Praveen (1983), "Population (1757–1947)", in Dharma Kumar (ed.), The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 2, C.1757-c.1970, Cambridge University Press, pp. 463–522, ISBN 978-0-521-22802-2

- Damodaran, Vinita (2015), Damodaran, Vinita; Winterbottom, Anna; Lester, Alan (eds.), "The East India Company, Famine and Ecological Conditions in Eighteenth-Century Bengal", The East India Company and the Natural World, Palgrave Studies in World Environmental History, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 80–101, doi:10.1057/9781137427274_5, ISBN 978-1-137-42727-4, retrieved 30 July 2021

- Dyson, Tim (27 September 2018). "Mughal Decline to Early British Rule". A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198829058.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

- Johns, Alessa (1999). "Hunger in the Garden of Plenty: The Bengal Famine of 1770". Dreadful Visitations: Confronting Natural Catastrophe in the Age of Enlightenment. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315022789. ISBN 9781136683893.

- Khan, Abdul Majed (1969). The Transition in Bengal, 1756–75: A Study of Saiyid Muhammad Reza Khan. Cambridge South Asian Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-04982-5.

- Dutta, Rajat (2019). "Subsistence crises and economic history : A study of eighteenth-century Bengal". A Cultural History of Famine: Food Security and the Environment in India and Britain. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315316529-3. ISBN 978-1-315-31652-9. S2CID 159367089.

- Roy, Tirthankar (10 September 2021), An Economic History of India 1707–1857, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-00-043607-5

External links

- Section VII Archived 11 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine from Dharampal, India Before British Rule and the Basis for India's Resurgence, 1998.

- Chapter IX. The famine of 1770 in Bengal in John Fiske, The Unseen World, and other essays

- R.C. Dutt, The Economic History of India.