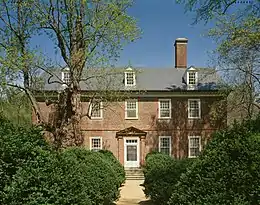

Benjamin Harrison IV (1693 – July 12, 1745[1]) was a colonial American planter, politician, and member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. He was the son of Benjamin Harrison III and the father of Benjamin Harrison V, who was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the fifth governor of Virginia.[2][3] Harrison built the homestead of Berkeley Plantation, which is believed to be the oldest three-story brick mansion in Virginia and is the ancestral home to two presidents: his grandson William Henry Harrison, and his great-great-grandson Benjamin Harrison.[4] The Harrison family and the Carter family were both powerful families in Virginia, and they were united when Harrison married Anne Carter, the daughter of Robert "King" Carter.[5] His family also forged ties to the Randolph family, as four of his children married four grandchildren of William Randolph I.[1][2]

Biography

Benjamin Harrison IV was born in a small house on the plantation named "Berkeley Hundred" or "Berkeley Plantation".[5] The immigrant of his family is thought to have come from London and earlier from Northampton.[6] He completed his studies at The College of William & Mary and became the family's first college graduate.[7] He settled on his family estate and increased his land holdings, as his ancestors had done.[3][7]

Around 1722, Harrison married Anne Carter, whom William Byrd II described as "a very agreeable girl",[1] and he managed and received profits from her father's land as part of her dowry.[8] Carter entailed this land to Harrison's son Carter Henry Harrison.[8] Harrison built a Georgian-style three-story brick mansion on a hill overlooking the James River in 1726 using bricks that were fired on the plantation.[9][nb 1] Berkeley has a distinction shared only with Peacefield in Quincy, Massachusetts, as the ancestral home of two presidents.[4] In 1729, Harrison purchased 200 acres of the Bradford plantation from Richard Bradford III.[11] From 1736 to 1742, he represented Charles City County, Virginia in the House of Burgesses.[12]

Harrison and his wife had 11 children:[1]

- Elizabeth (born ~1723)[1] married Peyton Randolph, the son of Sir John Randolph, the grandson of William Randolph I, and the first President of the Continental Congress.[2]

- Anne (born ~1724)[1] married William Randolph III, the son of William Randolph II and the grandson of William Randolph I, and had eight surviving children.[2][13] Her descendants include Captain Kidder Breese.

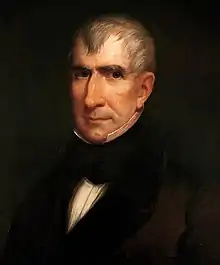

- Benjamin (born ~1726)[1] married Elizabeth Bassett.[2] His third son was President William Henry Harrison.[3] His descendants include Congressman John Scott Harrison and President Benjamin Harrison.[2]

- Lucy (born ~ca.1792–1793)[1] married Edward Randolph Jr., the son of Edward Randolph Sr. and the grandson of William Randolph I.[1]

- Hannah (born ~ – ~1745)[1]

- Carter (born ~1732)[1] married Susannah Randolph, the daughter of Isham Randolph, and they had six children.[13] His descendants include Chicago Mayors Carter Henry Harrison III and his son Carter Henry Harrison IV.[14]

- Henry (~1734 – ~1736) who died in infancy.[1]

- Henry (born ~1736–1772)[1] who served as a captain under Major General Edward Braddock in the French and Indian War and under Lieutenant Colonel George Washington. Lived at Hunting Quarter in Sussex County.

- Robert (born ~1738)[1]

- Charles (b. ~1740 – d. 1793) who was colonel of the 1st Continental Artillery Regiment.[1]

- Nathaniel (b. ~1741–d. 1792) who became Sheriff of Prince George County in 1779 and a member of the Virginia House of Delegates in 1781–1782. In 1760, he married Mary Ruffin, daughter of Edmund Ruffin and they had four children. He married Anne Gilliam in 1768 and they had six children. His descendants include J. Hartwell Harrison.[15]

Harrison in 1745 was struck by lightning and killed, with one daughter, Hannah. Some reports incorrectly say his "two youngest daughters" were killed in 1745 when lightning struck his house.[1][nb 2] Harrison's will expressed his intent to be buried near his son Henry,[1] and it broke with the British tradition of primogeniture by leaving large amounts of wealth to all of his children.[16] His oldest son Benjamin became responsible for the six plantations that comprised Berkeley, along with the manor house, equipment, stock, and slaves.[7] Eight other plantations were divided among the remaining sons, and his daughters were given cash and slaves.[7]

One source indicates that Harrison's tomb is located on the grounds of the "old Westover Church",[11] but another states that he was buried in his family's cemetery.[12]

Notes

- ↑ Meg Greene reported that the mansion was built after Harrison received "a grant of twenty-two thousand acres of land", but does not state precisely when he acquired the land.[10]

- ↑ Reports around the incident do not name the two others who died, but W.G. Stanard named them as "Lucy" and "Hannah" in 1924. The survival of Lucy is well documented, which suggests that Stanard's report is at least partially in error.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Cowden, Gerald Steffens (July 1981). "Spared by Lightning: The Story of Lucy (Harrison) Randolph Necks". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Historical Society. 89 (3): 294–307. JSTOR 4248494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cutter, William Richard, ed. (1915). "The Harrison Line". New England Families, Genealogical and Memorial: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of Commonwealths and the Founding of a Nation. 3. Vol. IV. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. pp. 2088–2089.

- 1 2 3 Abbot, Willis John (1895). "The Harrison Family". Carter Henry Harrison: A Memoir. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. pp. 1–23. ISBN 9780795020988.

- 1 2 Haas, Irvin (1991) [1976]. "William Henry Harrison". Historic homes of the American Presidents (Second ed.). New York: David McKay Company Inc. pp. 47–54. ISBN 9780486267517.

- 1 2 Roberts, Bruce (1990). Kedash, Elizabeth (ed.). Plantation Homes of the James River. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 10, 32. ISBN 978-0-8078-4278-2.

- ↑ Harrison, Francis Burton. “Commentaries upon the Ancestry of Benjamin Harrison: V. Benjamin Harrison of Aldham and Stationer Harrisons.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 54, no. 3, 1946, pp. 244–54. JSTOR website Retrieved 30 Sept. 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Moore, Anne Chieko (2006). "The Harrison Heritage". In Hale, Hester Anne (ed.). Benjamin Harrison: Centennial President. First Men, America's Presidents. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-60021-066-2.

- 1 2 Mooney, Barbara Burlison (2008). "Reason Reascends Her Throne: The Impact of Dowry". Prodigy Houses of Virginia: Architecture and the Native Elite. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-8139-2673-5.

- ↑ Renouf, Norman; Renouf, Kathy (1999). "Central Virginia: Charles City County". Romantic Weekends in Virginia, Washington DC and Maryland. Edison, New Jersey: Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-55650-835-6.

- ↑ Greene, Meg (2007). "Child of the Revolution". William H. Harrison. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8225-1511-1.

- 1 2 Bradford, David Thomas (1993). "Philemon and Mary: The Harrisons". The Bradfords of Charles City County, Virginia, and Some of their Descendants, 1653–1993. Gateway Press. p. 84.

- 1 2 O'Neill, Patrick L. (2010). "William Henry Harrison". Virginia's Presidential Homes. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-7385-8608-3.

- 1 2 Page, Richard Channing Moore (1893). "Randolph Family". Genealogy of the Page Family in Virginia (2 ed.). New York: Press of the Publishers Printing Co. pp. 249–272.

- ↑ Tyler, Lyon Gardiner, ed. (1915). "Fathers of the Revolution". Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography. Vol. II. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Hooker, Mary Harrison (1998). All Our Yesterdays. pp. 25–30.

- ↑ Kornwolf, James D.; Kornwolf, Georgiana Wallis (2002). "England in Virginia, 1585-1776". Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America. Vol. Two. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-8018-5986-1.