Benjamin Wallace | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) | |

| Born | Benjamin E. Wallace October 4, 1847 Johnstown, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 7, 1921 (aged 73) Rochester, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Burial place | Mount Hope Cemetery, Peru, Indiana, U.S. |

| Known for | |

| Spouses |

|

Benjamin E. Wallace (October 4, 1847 – April 7, 1921) was an American circus owner and Civil War veteran who founded the Hagenbeck–Wallace Circus, the second-largest circus in America.

Early life

Wallace was born on October 4, 1847, near Johnstown, Pennsylvania, to Ephraim and Rebecca Wallace.[1] His family were of Scottish lineage and his grandfather fought at the Battle of Tippecanoe under General Harrison.[2]

Wallace's father Ephraim brought his family of five daughters and five sons, first to Rochester, then to Peru, by wagon in 1863.[2] His father died of malaria in 1864 and three of his brothers and a sister died soon thereafter.[2] His sister, Alice, later married Pim Sweeney, director of Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago.[2]

Wallace enlisted in the American Civil War in the 13th Indiana Infantry Regiment in February 1865.[2] The war was over before he got into any fighting in Virginia, though he made $250.00 from trading with other soldiers before being discharged.[2]

Career

Wallace attended circus show sales including a sale of equipment of the W.C. Coup show in 1882 which had gone bankrupt.[1] Wallace purchased the Nathan and Company travelling menagerie in 1883.[3] On January 25, 1884, a fire burned the furniture warehouse where the animals were kept and killed all of them.[3]

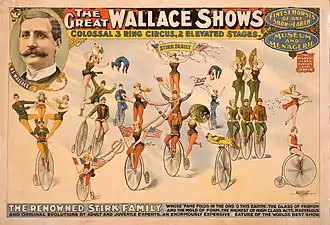

On April 26, 1884, Wallace opened his own circus show called Wallace and Co.'s Great World Menagerie, Grand International Mardi Gras, Highway Holiday Hidalgo and Alliance of Novelties.[3] The show left Peru by horse and wagon and would tour in Indiana, Kentucky and Virginia.[4] The name of the shows would later change to The Great Wallace Shows.[1] The shows featured acts such as Willie Cash and his performing dogs, A.G. Fields the singing clown and the Walton Brothers who were acrobats.[5] In 1890, Wallace bought out his partner James Anderson and became the sole owner and manager of the show.[6]

In 1892, Wallace bought 220 acres (89 ha) of land along the bank of the Mississinewa River from Gabriel Godfroy, the son of Miami war chief Francis Godfroy.[6] Wallace used the land to build barns and buildings including a cat barn, an elephant barn, a wagon shed, a carpenter shop and a foundry.[6] Wallace acquired and merged the La Pearl circus in 1899.[7]

In 1907, Wallace purchased the Carl Hagenbeck Circus and incorporated it into his own show forming the Hagenbeck–Wallace Circus.[1] Wallace bought out all of his investors in the Hagenbeck–Wallace Circus except for John C. Talbot of Denver, Colorado.[8] A contemporary Peru newspaper article reported that since Wallace owns most of the stock, his holdings were now "greater than those of any other showman in the country and probably the world."[1] Wallace merged part of the Norris & Rowe circus in 1910.[7]

In 1913, Wallace sold the circus to the American Circus Corporation.[9] He kept the winter quarters and rented it to circuses until 1921 when he sold it to the American Circus Corporation.[9]

Personal life and death

His first marriage was to Dora M. Blue until her death in 1870.[2] His second marriage was to Florence E. Fuller, daughter of Reuben Fuller, a hotel proprietor in Peru.[2]

In 1921, Wallace entered the Mayo Clinic in Rochester for routine hernia surgery.[2] Although the operation was a success he died unexpectedly on April 7, 1921.[1] He was buried in his family's plot in Mount Hope Cemetery, Peru.[2]

Legacy

Historian Kreig A. Adkins described Wallace as the "Circus King" and says he opened the door for Jeremiah Mugivan, Bert Bowers, and Edward M. Ballard, owners of the American Circus Corporation, to turn the circus business into an industry.[10]

Wallace was accused of horse thievery by a former employee.[11] The employee said that Wallace would tell someone called Peedad to hide around or lay in a wagon until a farmer climbed on the wagon and took the horses home.[11] Once the farmer was in bed, they would bring the horses back to the circus and the circus would leave town.[11]

The Ringling brothers purchased the winter quarters in 1929.[9] They owned the quarters until 1938 when the circus was moved to a warmer location.[9] The property was sold in 1941 and to minimize maintenance they burned the old circus wagons.[12] The winter quarters are now the site of the Circus Hall of Fame.[9]

See also

- Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 1903 United States Supreme Court case involving Wallace

- Hammond Circus Train Wreck, train wreck involving performers of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Newman, Nancy (July 15, 1986). "Benjamin E. Wallace". Peru Daily Tribune: Circus Edition. Peru, Indiana. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Condon 1964, pp. 3–6.

- 1 2 3 "The Great Wallace Shows". Circus Hall of Fame. June 17, 2021. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ↑ Adkins 2009, p. 10.

- ↑ Adkins 2009, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Adkins 2009, p. 13.

- 1 2 Charleton 1986, p. 592.

- ↑ Adkins 2009, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Wallace Circus & American Circus Winter Quarters". Discover Indiana. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ↑ Adkins 2009, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Hanners 1993, p. 134.

- ↑ Salaz, Susan (April 8, 2020). "Inside the 'Circus Capital of the World'". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

Sources

- Adkins, Kreig A. (May 27, 2009). Peru: Circus Capital of the World. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738560717. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- Charleton, James H. (1986). Recreation in the United States. National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- Condon, Chalmer (July–August 1964). Bandwagon – Vol. 8, No. 4 – 80 Years of Circus in Peru. Columbus, Ohio: Circus Historical Society. ASIN B002DGM2PK. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- Hanners, John (1993). "It was Play Or Starve". Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 9780879725877. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.