The Marquess of las Hormazas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1867 Pamplona, Spain |

| Died | 1937 (aged 69–70) Bilbao, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | landowner |

| Known for | politician |

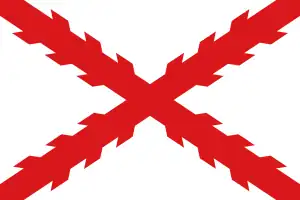

| Political party | Carlism |

Bernardo Elío y Elío, 7th Marquess of Las Hormazas (1867–1937), was a Spanish aristocrat and politician. He supported the Carlist cause. During the late Restoration period he formed part of the regional Aragon party executive, but is known mostly as the local Traditionalist leader in the province of Gipuzkoa, especially during the lifetime of the Second Spanish Republic; he briefly served also in the supreme party executive, but did not play a major role in shaping the nationwide party politics. He was a typical example of an inner-circle aristocrat ruling the local Traditionalist structures.

Family and youth

The Elíos, since the Mid-Ages related to Valle de Echauri,[1] during the Modern Period became owners of many estates, scattered across central and Northern Navarre.[2] Family representatives held various prestigious positions, for centuries served in the Cortes[3] and were briefly care-takers of Virreinato de Navarra.[4] By means of marriages they acquired Marquesado de Vesolla in the early 18th century and Marquesado de las Hormazas in the early 19th century.[5] The holder of both titles and Bernardo's grandfather, Francisco Javier Elío Jiménez-Navarro (1800–1880), passed the Vesolla title to his oldest son, while the Las Hormazas title went to the second son and Bernardo's father, Joaquín Elío Mencos (1832–1876).[6] The family was heavily related to other aristocratic Navarrese families, like Marquéses de Lealtad,[7] Marquéses de Vadillo,[8] Duqués de Bailén,[9] Condes de Guenduláin[10] and other.

Joaquín Elío married his cousin, Petra Celestina Elío Arteta (1836–1909), descendant to another Navarrese landholder family and already a widow.[11] It is not clear whether the couple settled in Pamplona[12] or at one of family estates;[13] they had at least 3 children, Bernardo, Eduardo[14] and Francisca Javiera.[15] Following premature death of Joaquín Elío, result of his engagement in the Third Carlist War, in the late 1870s the widow and children settled in Zaragoza;[16] the family Navarrese property was embargoed and possibly expropriated,[17] while her well-off relatives lived in the Aragón capital.[18] The young Bernardo was growing up in Zaragoza, though he has always cherished his Navarrese heritage.[19] He studied law at the Zaragoza University[20] and graduated probably in the late 1880s,[21] though he has never practiced.[22]

In 1895[23] Elío married Teresa Zubizarreta Olavarría (1870–1936),[24] descendant to a distinguished Gipuzkoan landowner family from Ataun in the Tolosa county.[25] The couple settled in Zaragoza, though later they moved to Zubizarreta properties in Gipuzkoa; it is not clear how many children they had. The only one known was Bernardo Elío Zubizarreta, the 8. Marqúes de las Hormazas;[26] marginally involved in Carlism in the early Francoist era,[27] he did not become a public figure. Neither did any of the Elío Lopetedi[28] grandchildren;[29] following death of Bernardo Elío Lopetedi the 9. Marqués de las Hormazas in 2016[30] the title is vacant.[31]

Numerous Elío's more distant relatives grew to prominence. Among his predecessors many from the Elío Ezpeleta, Elío y Elío and Zubizarreta branches distinguished themselves as legitimist military or officials, serving either in the First or/and Third Carlist War. His paternal uncle Alvaro Elío Mencos served as president of the Alava diputación in the late 19th century. Among his paternal cousins, Luis Elío Elío Magallón was a conservative Navarrese senator in 1907–1920;[32] Francisco Javier González de Castejón Elío held various ministerial posts in conservative cabinets of 1900–1914; Miguel González de Castejón Elío was a military and preceptor of the future king Alfonso XIII, later made Conde de Aybar.[33] His brother-in-law, Eusebio Zubizarreta, was a Carlist deputy to the Cortes in 1893–1896.[34] Many other relatives intermarried with aristocratic families, usually related to the Vasco-Navarrese area.[35]

Early public activity

Many members of the Elío family sided with the Carlists since the 1830s, and a few like Joaquín Elío Ezpeleta grew to iconic figures of the movement.[36] Bernardo's father Joaquín Elío Mencos prepared the Pamplona rising in 1869;[37] captured and sentenced to death he was eventually condemned to exile on the Mariana Islands, but escaped in Cádiz[38] and commanded a battalion during the Third Carlist War.[39] Apprehended again few years later, he perished[40] in captivity.[41] Bernardo's father-in-law was the nephew of Tomas Zumalacárregui, a half-mythical Traditionalist hero, and engaged in the legitimist coup of 1860.[42] Bernardo himself started to demonstrate his Carlist zeal already during the academic period in the mid-1880s, first signing letters protesting alleged mistreatment of the Pope[43] and then – as member of Aragonese Carlist youth – manifesting his adherence to the claimant and his son Don Jaime.[44] In 1890 he took part in Catholic Congress in Zaragoza[45] and in 1891 embarked on a journey to Venice to pay his respect to the pretender.[46]

As Elío remained among relatively few high aristocrats loyal to Carlos VII, he usually featured among first signatories of various open letters, circulated by the party activists.[47] Since the early 1890s Elío started to appear along provincial prestigious Carlist personalities, e.g. in 1892 he co-presided a Traditionalist meeting in Zaragoza.[48] During the honeymoon trip of 1895 he and his newly wed wife changed plans and detoured to Switzerland to meet the claimant and receive his best wishes.[49] The same year Las Hormazas for the first time took part in a meeting of the nationwide Carlist executive in Madrid, headed by the party political leader Marqués de Cerralbo.[50] In 1898 he was rumored to run on the Carlist ticket for the Cortes; newspapers speculated he would stand in the Navarrese[51] district of Aoiz,[52] but eventually the news was not confirmed.

In the early 20th century Elío was already a regular prestigious guest at various local Zaragoza and Aragón Carlist rallies. He was opening new círculos,[53] featured prominently during party events like Fiesta de los Mártires de la Tradición,[54] presided over rallies of the party youth,[55] donated money to Traditionalist prints,[56] co-signed various open letters[57] and appeared in first row during related religious services;[58] the claimant honored him with personal letters.[59] In 1907 he became vice-president of Juventud Carlista de Zaragoza;[60] at the same time he was also deputy chairman of Junta Tradicionalista of Zaragoza and probably also member of the Aragonese Junta Regional.[61] Following the 1905 death of the unquestioned Aragón Carlist leader Francisco Cavero the regional party leadership was contested by Duque de Solferino, Manuel Serrano Franquini, Pascual Comín and José María del Campo; Elío and Francisco Cavero Esponera formed the second row of aspiring politicians.[62]

Aragón party executive

In 1909 Elío for the first, and, as it would turn out in the future, also the last time, decided to stand in electoral competition. He represented the Carlists on a broad Right-wing ticket of Asociación Social Católica when running to the town hall[63] from the Pilár district[64] and emerged successful;[65] the victory terminated the string of earlier Carlist electoral defeats.[66] During the next few years he was recorded in local press as the ayuntamiento councilor, usually during charity events[67] and other official ceremonies,[68] e.g. meetings with local hierarchs, like civil governor of the Zaragoza province.[69] His last assignment identified was the 1912 nomination to Junta Provincial de Instrucción Pública;[70] indeed, he demonstrated particular interest in education, animating rallies against secular schools.[71]

At least in 1909 Las Hormazas entered Junta Regional de Aragón;[72] it is not clear whether at the time he was also member of the provincial Zaragoza party executive, though he held vice-presidency of Juventud Tradicionalista in the city.[73] In the early 1910s he went on with usual and rather traditional party ceremonial duties, e.g. speaking at close meetings[74] or taking part in related religious services.[75] In his early 40s, since 1910 he presided over the freshly set up Zaragoza branch of Requeté, at the time the sporting and outdoor organization for the youth.[76] In the regional executive he was also responsible for co-ordination of charity work.[77] Elío is not mentioned as engaged in nationwide Carlist politics;[78] historiographic works on Traditionalism of the early 20th century ignore him and it is not clear what – if any – was his position in numerous conflicts tormenting the party at the time, like mounting conflict between the claimant and the key theorist Vázquez de Mella, position versus growing peripheral nationalisms or the question of a broad conservative alliance.

Though resident in Zaragoza and active in the regional Aragón party structures, Las Hormazas maintained links to his native Vasco-Navarrese area; e.g. in 1909 he was noted in San Sebastián taking part in the funeral mass to the late Carlos VII.[79] In the mid-1910s Elío focused on remnants of his Navarrese estates in Valle de Baztán, as construction of Tren Txikito, the Elizondo-Irún narrow-gauge railway line, affected his property related to the former Señorio de Bertiz.[80] None of the sources consulted confirms when he left Zaragoza and settled in Gipuzkoa, most likely at the Zubizarreta property inherited by his wife in San Sebastián. In 1914 he was for the first time noted as engaged in the provincial Gipuzkoan Carlist structures, at that time led by Marqués de Valde-Espina.[81] Also the last Zaragoza-based information related to the Elío couple comes from early 1914.[82]

Gipuzkoa party executive

During the Mellista crisis of 1919 Las Hormazas sided with the claimant. As representative of Gipuzkoa[83] he was one of 4 aristocrats present[84] during a grand meeting known as Magna Junta de Biarritz, supposed to set the new course of the movement. In the early 1920s he moderately engaged in Jaimista propaganda[85] and purchased shares in Editorial Tradicionalista, a Donostía-based Carlist publishing house.[86] However, the Primo de Rivera coup of 1923 brought political life in the country to the standstill; throughout the rest of the decade Elío was recorded in the press only on the societé columns,[87] as he apparently withdrew into privacy.

Few weeks after the fall of Primo, in early 1930, the Gipuzkoan Jaimistas reconstituted their provincial executive; Las Hormazas was temporarily elected its president,[88] the choice confirmed a few months later during a grand rally in Zumarraga.[89] As provincial jefé in October he issued a manifesto which called to recognize distinct identity of the Vasco-Navarrese provinces, including the Basque language and separate legal establishments,[90] all to be incorporated within “esta hermosa Federación de Naciones”.[91] In 1931 he suggested setup of “Pro Reivindicaciones Vascas”, a junta expected to work for re-constitution of “nuestras libertades”;[92] however, he opted against "organización supraprovincial”.[93]

In 1930-1931 Elío emerged strongly in favor or re-unification of all Traditionalist branches,[94] initially on basis of a Catholic alliance.[95] When in late 1931 the process was completed with emergence of united Comunión Tradicionalista he saw his powers somewhat diminished; though he remained the provincial jefé of CT, in public it seemed that he co-presided with the former Integrist leader, Juan Olazabal,[96] as the two appeared as peers on many assemblies,[97] especially at the 1931 funeral services to the defunct Don Jaime.[98] Though he was confirmed as Gipuzkoan jefe in 1932,[99] the double-leadership pattern was maintained as both Elío and Olazabal entered the national party executive.[100]

During early stages of debates on Vasco-Navarrese autonomy Elío remained active[101] and called to abolish the government-imposed comisiones gestoras,[102] but in his 1932 addresses he was more ambiguous;[103] historiographic studies do not list him as involved.[104] Still member of the national executive in the mid-1930s,[105] in 1933 he was first noted as suffering from poor health[106] and got temporarily replaced.[107] In 1934-1935 he was noted on few rallies[108] and entertained the new party leader Manuel Fal in the province,[109] though at key gatherings he seemed in the second row.[110]

It is not known whether Elío was involved in anti-Republican conspiracy of 1936.[111] In Gipuzkoa the coup failed; Las Hormazas was detained and ended up in the Bilbao Angeles Custodios prison. Since the Basque government did not deploy autonomous police to protect the building during the unrest,[112] caused by the nationalist bombing raid over the city, the prison was entrusted to the UGT militia unit. On January 4 socialist militiamen executed around 100 prisoners;[113] some were killed by hand grenades thrown into cells, some were shot and some were reportedly slashed with machetes.[114] It is not clear how exactly Elío died.[115]

Footnotes

- ↑ señorio of Elio, acquired by the family in the Middle Ages, throughout decades remained a rather tiny estate. In the early 19th century it consisted of 66 acres and supported a population of 15 people; it was leased to 4 other landholders, John Lawrence Tone, The Fatal Knot: The Guerrilla War in Navarre and the Defeat of Napoleon in Spain, Raleigh 2018, ISBN 9781469616926, p. 218

- ↑ in the early modern times the Elíos by means of marriage took possession of estates in Subiza; also in early modern times they merged with the family of Ayanz, owners of estates in Valle de Longuida near Aoiz, and then with the Jaureguizar, related to Valle de Baztan, José María Sesé Alegre, Poder y elites an la Navarra tardomoderna. Las familias Aperregui y Elío, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 15 (1993), p. 269

- ↑ Sesé Alegre 1993, p. 269

- ↑ Sesé Alegre 1993, pp. 271–272

- ↑ Lucio R. Perez Calvo, El Marquesado de Las Hormazas, [in:] Hidalguía LXI (2014), p. 481

- ↑ Pedro Joaquín Elio Mencos, Marques De Homazas entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- ↑ in 1824 the title of Marqués de Lealtad was granted to Bernardo Elío Leizaur, a very distant paternal relative

- ↑ Bernardo Elío y Elío’s paternal aunt, Manuela Elío Mencos, married Pedro González de Castejón, Marqués de Vadillo

- ↑ Bernardo Elío y Elío’s paternal cousin, Manuel González de Castejón Elío, married duquesa de Bailén, María de la Encarnación Fernández de Córdoba y Carondelet

- ↑ Bernardo Elío y Elío’s paternal grandfather married María Micaela Mencos Manso de Zúñiga, daughter to Conde de Guenduláin; the title went to her brother, i.e. Bernardo Elío y Elío’s maternal uncle

- ↑ María Zozaya Montés, El Casino de Madrid: ocio, sociabilidad, identidad y representación social [PhD thesis Universidad Complutense], Madrid 2008, p. 257

- ↑ Bernardo Elío y Elío was born in Pamplona, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. 29, Sevilla 1960, p. 126

- ↑ it is not clear what exactly were the estates owned by the family. One of them might have been so-called señorio de Bertiz, which in the 18th century passed from the Alduncín family to the Elios. Eventually the property went to Bernardo Elío y Elío’s paternal uncle, Fausto Elío Mencos; in the 1880s he sold the señorio, Andoni Esparza Leibar, El parque natural del Señorio de Bertiz, s. l. 2001, ISBN 8495746158, p. 58. However, in the 1910s Bernardo Elío y Elío owned some property along the Elizondo-Irun railway line, which might have been some remnants of the Bertiz estate

- ↑ El Correo Español 11.03.09, available here. There is no further information about his fate except that he got married, La Epoca 28.11.96, available here

- ↑ she married Jacinto Pitarque and settled in Zaragoza. Their son Joaquín Pitarque Elío became the dean of Aragon agricultural engineers

- ↑ the widow spent the rest of her days in Zaragoza, El Correo Español 11.03.09, available here

- ↑ embargoing properties of individuals engaged in Carlist insurrection was standard procedure, applied also to Joaquín Elío, see La Correspondencia de España 02.07.75, available here. At times the embargo could have lasted for years, at times it could have led to expropriation. It is not clear what was the procedure followed in case of the Elío properties

- ↑ she was “emparentada con las principales familias de esta ciudad”, La Correspondencia de España 12.03.09, available here; the families in question were probably duques de Bailén and marqueses de Vadillo, La Epoca 14.03.09, available here

- ↑ in 1893 Bernardo Elío counted himself among “los que han nacido en Navarra, y han respirado su puro ambiente”, El Tradicionalista 21.06.93, available here

- ↑ Ferrer 1960, p. 126

- ↑ compare e.g. Memoria del Curso, Zaragoza 1883, available here. As the Zaragoza University student he signed protest letter in 1884, El Siglo Futuro 04.12.84, available here

- ↑ none of the sources consulted claims that he practiced as lawyer; he has never been referred in the press as “abogado” or similar. There is one historiographic work which mentions “abogado tradicionalista Bernardo Elío (marqués de las Hormazas)”, Carmelo Landa Montenegro, Bilbao, 4 de enero de 1937: memoria de una matanza en la Euskadi autónoma durante la Guerra Civil española, [in:] Bildebarrieta 18 (2007), p. 90. No source specifies what was the source of Elío’s income; he probably lived off the land rent

- ↑ El Correo Español 21.03.95, available here; apparently he did not seek the royal permission to marry, required in case of aristocracy; in 1915 he retractively tried to settle the issue, Revista de Historia y Genealogia Española 1915, p. 367, available here

- ↑ she died on August 21, 1936. It is not clear whether her death was anyhow related to outbreak of the civil was in general or detention of her husband in particular. On July 4, 1936 she was reported in the press as “enferma”, ABC 04.07.36, available here

- ↑ Teresa Zubizarreta Olavarria entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- ↑ Bernardo Elío Zubizarreta got his marquesado confirmed by Franco in 1949, see BOE 344 (1949), available here

- ↑ in the 1940s he was considered “falcondista antifranquista”, Manuel Santa Cruz Alberto Ruiz de Galarreta, Apuntes y documentos para la historia del Tradicionalismo español, 1939-1966, Madrid 1979, vol. 4–5, p. 109, also Manuel Martorell Pérez, Antonio Arrue, Euskaltzaindiaren suspertzean lagundu zuen karlista, [in:] Euskera 56 (2011), p. 856

- ↑ he had at least 7 grandchildren, Bernardo de Elío Zubizarreta entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- ↑ Carmen Elío Lotepedi commenced the de Ovando y de Elío line, while José Antonio Elio Lopetedi commenced the Elío Sanz de Vicuña branch

- ↑ Bernardo Elio Lopetedi got his marquesado confirmed in 1985, ABC 08.09.85, available here

- ↑ Arcadio Calvo Gómez, Profesionales del ámbito de la juventud de varios países de Europa vuelven a Almagro en el segundo curso de atención especializada a los jóvenes, [in:] Ciudad-Almagro service, available here

- ↑ Elío Magallon, Luis entry, [in:] Gran Enciclopedia de Navarra, available here

- ↑ Miguel González de Castejón y Elío entry, [in:] Real Academia de Historia service, available here

- ↑ Zubizarreta Olavarria, Eusebio entry, [in:] Aunamendi Eusko Entziklopedia, available here

- ↑ Esteban de Garibay, Ilustraciones Genalógicas de los Linajes Vascongados, Donostía 1922, pp. 63–64

- ↑ apart from Joaquín Elío Ezpeleta, also his brothers Salvador Elío Ezpeleta and Luis Elío Ezpeleta became distinguished Carlist leaders, the former as president of Real Tribunal Superior Vasco-Navarro de Justicia, and the latter as rector of the Oñate university, both operating at the territory held by the Carlists during the Third Carlist War.

- ↑ Juan Cruz Labeaga Mendiola, Memorias de exilio de un clérigo carlista (1868-1869), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 59 (1998), pp. 830, 838, 848

- ↑ from Cádiz in unclear circumstances he made it to France, and then passed to the Carlist-held Spanish territory, Elío y Mencos, Joaquín María entry, [in:] Gran Enciclopedia de Navarra, available here

- ↑ as commander of the 5. Navarrese battalion; in this role he is featured in La corte de Estella, a story by Valle-Inclan. As “meagre, tall, elderly man”, who was “stern in the exaction of discipline” he appears also in an English novel, see John Augustus O’Shea, Romantic Spain, London 1887

- ↑ always of poor health, Joaquín Elío Mencos died of tuberculosis, La Correspondencia de España 22.02.76, available here

- ↑ Esparza Leibar 2001, p. 59

- ↑ La Iberia 21.01.87, available here

- ↑ El Siglo Futuro 04.12.84, available here

- ↑ El Siglo Futuro 04.12.86, available here

- ↑ La Unión Católica 05.08.90, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 08.10.91, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 16.11.92, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 31.03.92, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 22.07.95, available here

- ↑ La Lealtad Navarra 13.03.95, available here

- ↑ El Eco de Navarra 08.03.98, available here

- ↑ Las Provincias 12.03.98, available here

- ↑ e.g. in 1905 he was behind presidential table when opening Circulo de Juventud Carlista in Zaragoza, El Correo Español 20.03.05, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 07.04.06, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 11.02.07, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 03.04.08, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 16.08.06, available here

- ↑ e.g. in 1906 he was among most prominent participants of the funeral mass to the defunct mother of the claimant, El Correo Español 11.04.06, available here

- ↑ in 1907 the claimant sent Elío his personal condolences upon news of death of his mother, a gesture reserved only for major party personalities, El Correo Español 10.08.07, available here

- ↑ El Tradicionalista 27.01.07, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 16.01.07, available here

- ↑ Elío was also active in anti-duel organizations, holding executive position in the local Zaragoza Liga Anti-Duelista, La Epoca 10.07.05, available here

- ↑ La Correspondencia de España 07.11.09, available here

- ↑ La Correspondencia de España 12.11.09, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 13.12.09, available here, also La Correspondencia de España 07.01.10, available here, El Tradicionalista 06.12.09, available here

- ↑ Enrique Bernad Royo, Catolicismo y laicismo a principios de siglo. Escuelas laicas y católicas en Zaragoza, Zaragoza 1985, ISBN 8450516099, p. 85

- ↑ La Correspondencia de España 28.06.10, available here

- ↑ La Correspondencia de España 16.04.10, available here

- ↑ La Correspondencia de España 05.03.10, available here

- ↑ Gaceta de Instrucción Pública y Bellas Artes 03.04.12, available here

- ↑ El Siglo Futuro 16.03.10, available here

- ↑ Ferrer 1960, p. 126, B. de Artagan, Politicos del carlismo, Barcelona 1913, p. 271

- ↑ the president was Antonio Cavero y Esponera, Elío’s peer, born also in 1867, and son to an iconic Aragonese Carlist Francisco Cavero, La Correspondencia de España 07.01.10, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 29.11.09, available here

- ↑ La Correspondencia de España 31.05.10, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 03.11.10, available here

- ↑ La Tradicióñ 28.06.12, available here

- ↑ in a hagiographic Carlist print dedicated to most distinguished party personalities, published in 1913, Elío did not earn a separate entry; he was only mentioned in the chapter dedicated to Salvador Elío Ezpeleta, see B. de Artagan, Politicos del carlismo, Barcelona 1913, no separate entry, only a paragraph in, p. 271

- ↑ Heraldo Alaves 29.07.09, available here

- ↑ El Eco de Navarra 01.06.13, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 21.07.14, available here

- ↑ La Epoca 17.04.14, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 03.12.19, available here

- ↑ the other 3 were marqueses of Tamarit, Vesolla and Villores

- ↑ in 1920 Elío co-signed a letter of adhesion to Don Jaime; other recognizable signatories were Conde Rodezno, Joaquín Beunza, Marqués de Vessola, Pascual Comín and Marcelino Ulibarri, La Reconquista 07.02.20, available here

- ↑ El Correo Español 04.04.21, available here

- ↑ La Atalaya 15.09.25, available here, also La Voz de Aragón 16.04.29, available here

- ↑ El Sol 25.02.30, available here

- ↑ El Cruzado Español 13.06.30, available here

- ↑ in his October 1930 manifesto Elío referred to “progreso intelectual económico” and organization which “requiere la distinta fisonomía de sus Regiones, en el pleno ejercicio de sus fueros”; he also made claims about “indiscutible uso de sus idiomas seculares y característicos, tan injusta e insensatamente perseguidos en estos últimos años”, El Cruzado Español 24.10.30, available here

- ↑ El Cruzado Español 24.10.30, available here

- ↑ Elío called for Basque-minded organisations and individuals to unite, so that they “constituyan el frente único euskaldun y la única entidad dirigente que actue de aglutinante de todos los vascos en la reconquista de nuestras libertades en los históricos momentos presentes”

- ↑ Idioia Estornés Zubizarreta, La construction de una nacionalidad Vasca. El Autonomismo de Eusko-Ikaskuntza (1918-1931), Donostia 1990, ISBN 9788487471049, p. 339

- ↑ it seems that already in September 1930 Elío in some of his public statements included veiled calls for unification, see e.g. “Paz a los muertos! Ya les ha juzgado Dios! Recordemos lo bueno que hicieron y olvidemos lo malo, hijo de las flaquezas humanas”, El Cruzado Español 12.09.30, available here

- ↑ Estornés Zubizarreta 1990, pp. 265-266

- ↑ El Siglo Futuro 08.09.31, available here

- ↑ El Cruzado Español 18.12.31, available here

- ↑ 'El Cruzado Español 16.10.31, available here; following death of Don Jaime, Elío concluded his manifesto with "El Rey ha muerto. ¡Viva la Monarquía tradicional!", El Sol 06.10.31, available here

- ↑ his adjuntos were Juan Olazabal and Candido Recondo, El Cruzado Español 05.01.32, available here

- ↑ in 1932 the Carlist command structure included a body named Junta Suprema Vasco Navarra; it consisted of 4 men, each for every province, and Gipuzkoa was represented but Juan Olazabal. However, formally jefé provincial for Gipuzkoa was Elío, Antonio M. Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República Española: Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054, p. 78

- ↑ e.g. at a grand 1931 rally he called for recognition of “nuestra personalidad histórica” and was listed first among signatories of a related document, La Epoca 01.04.31, available here

- ↑ Heraldo Alaves 07.07.31, available here

- ↑ for Azpeitia see El Siglo Futuro 11.04.32, available here; for Villafranca de Oria see El Siglo Futuro 04.07.32, available here; for Vergara see El Siglo Futuro 15.11.32, available here

- ↑ see e.g. Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521207294, Estornés Zubizarreta 1990

- ↑ in August 1933 Elío was listed as member of “Junta Delegada de la Comunión Tradicionalista”, headed by Conde Rodezno; he was representing Gipuzkoa, El Siglo Futuro 05.08.33, available here; in 1934 he was still listed as “delegado regio”, El Siglo Futuro 28.07.34, available here

- ↑ see El Siglo Futuro 11.10.33, available here

- ↑ an unclear press notice of October 1933 named Elío as the Gipuzkoan party leader, but at the same time named Agustín Tellería as “presidente” of Junta Provincial Tradicionalista, Pensamiento Alaves 06.10.33, available here

- ↑ see e.g. El Siglo Futuro 20.06.34, available here, El Siglo Futuro 03.10.34, available here, Pensamiento Alaves 19.06.34, available here, El Siglo Futuro 23.10.34, available here

- ↑ El Siglo Futuro 06.12.34, available here

- ↑ at a grand Carlist rally in San Sebastian the key speakers were José Luis Zamanillo, Luis Hernando de Larramendi and Esteban Bilbao, all unrelated to Gipuzkoa; the provincial party leader Elío was present, but barely mentioned, La Nación 23.12.35, available here

- ↑ it is difficult to imagine that Elío, the party leader in one of the few provinces where Carlism remained a tangible force, was unaware of the unfolding conspiracy. However, none of scholarly works dealing with the Carlist plot of early 1936 mentions his name, see e.g. Blinkhorn 2008, Roberto Muñoz Bolaños, “Por Dios, por la Patria y el Rey marchemos sobre Madrid", [in:] Daniel Macías Fernández (ed.), David contra Goliat: guerra y asimetría en la Edad Contemporánea, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788461705504, pp. 143–169, Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936–1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, and other. In the monographic work on the Civil War in Gipuzkoa Elío is vaguely mentioned as “la máxima autoridad de la Comunión” in the province, but is not explicitly referred as engaged in conspiracy or paramilitary buildup, Pedro Barruso, Verano y revolucion - la Guerra civil en gipuzkoa, Donostía 1996, ISBN 9788488947611

- ↑ some sources claim there were no police units available to the government, see José Manuel Azcona Pastor, Julen Lezamiz Lugarezaresti, Los asaltos a las cárceles de Bilbao el día 4 de enero de 1937, [in:] Investigaciones históricas 32 (2012), pp. 230; some sources claim that the Basque government refused to deploy police troops fearing outbreak of hostilities between UGT and PNV, see Jon Juaristi, Turbas [in:] El Imparcial 25.06.14, available here

- ↑ full list in Azcona, Lezamiz 2012, pp. 235–6

- ↑ Juaristi 2014

- ↑ detailed accounts differ; one scholar identifies the perpetrators as "incontrolados" militants of CNT and UGT, Pedro Barruso Barés, La represión en las zonas republicana y franquista del País Vasco durante la Guerra Civil, [in:] Historia Contemporánea 35 (2007), pp. 653–681

Further reading

- Lucio R. Perez Calvo, El Marquesado de Las Hormazas, [in:] Hidalguía LXI (2014), pp. 473–497

- José María Sesé Alegre, Poder y elites an la Navarra tardomoderna. Las familias Aperregui y Elío, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 15 (1993), pp. 265–272