| Bethesda Methodist Chapel, Hanley | |

|---|---|

| |

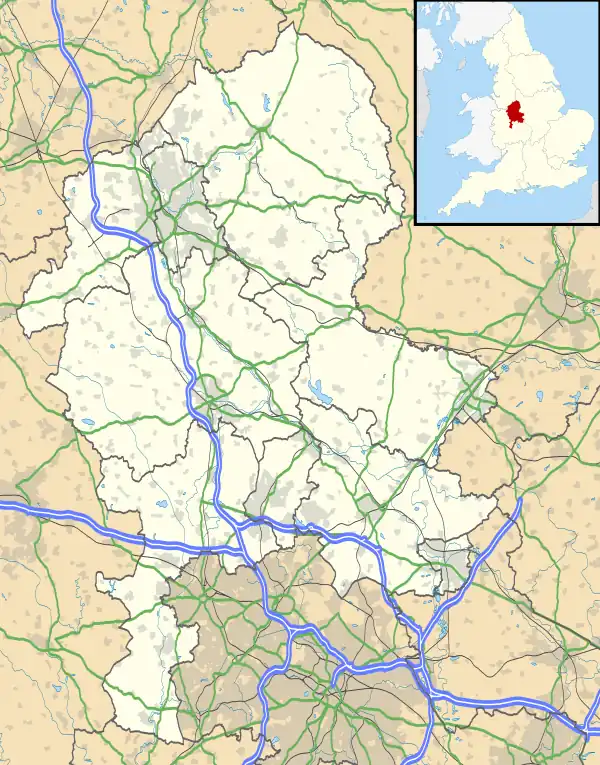

Bethesda Methodist Chapel, Hanley Location in Staffordshire | |

| 53°01′24″N 2°10′37″W / 53.0233°N 2.1769°W | |

| OS grid reference | SJ 882 473 |

| Location | Albion Street, Hanley, Staffordshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Methodist |

| Website | Bethesda Methodist Chapel |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Redundant |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 19 April 1972 |

| Architect(s) | J. H. Perkins Robert Scrivener |

| Architectural type | Chapel |

| Groundbreaking | 1819 |

| Completed | 1887 |

| Closed | 29 December 1985 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Brick with stuccoed facade and slate roof |

Bethesda Methodist Chapel is a disused Methodist chapel, in Hanley, Staffordshire, England. One of the largest Nonconformist chapels outside London, the building has been known as the "Cathedral of the Potteries", being "one of the largest and most ornate Methodist town chapels surviving in the UK".[1]

The first Methodist chapel on the site was built by the Methodist New Connexion in the late 18th century. Finding the building too small for their growing membership, the congregation replaced it with the current building in 1819, to the designs of a local amateur architect. The chapel is built over two stories and is in the Italianate style, with further work to expand the building completed in 1859 and 1887.

It became a Grade II* listed building in 1972, but this did not prevent it deteriorating. The chapel was closed for active worship in 1985, the size of the congregation having diminished. After passing through a number of owners, it was acquired by the Historic Chapels Trust in 2002 and is undergoing an extensive restoration scheme.

History

In 1779, the congregation of Hanley Wesleyan Chapel were expelled from the chapel for supporting Alexander Kilham. Kilham denounced the Methodist conference for giving too much power to church ministers, at the expensive of the laity; his disagreements led to a schism in the Methodist church and his founding of the Methodist New Connexion. In Hanley, the New Connexion congregation, foremost led by William Smith, Job Meigh and George and John Ridgway, initially met in the house of one of its prominent members, and then acquired a coach-house at the corner of Albion Street that was converted into a meeting house. During the following year the first chapel was built on the site with seating for 600 people.[2] It was formally opened by Wiliam Thom, the first president of the New Connexion, and Alexander Kilham, its secretary.[3] This chapel was the head of the Hanley Circuit, and by 1812 this Circuit was the strongest in the New Connexion. During the previous year the chapel had been expanded to seat 1,000. It was still too small for the size of the congregation and was demolished and replaced by the present chapel in 1819.[2]

Plans for the new chapel were drawn up by J. H. Perkins, a local school master, with seating for 2,500.[4] In 1859 a colonnade was added to the front of the chapel, with a window and cornice above.[2] This was designed by Staffordshire architect Robert Scrivener.[5] Further alterations were made in 1887, including the extension of the minister's vestry, replacement of the windows and renewal and restoration of the pews.[2][5]

The building is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a Grade II* listed building, having been designated in 1972.[6] However, it has been placed on the Heritage at Risk Register.

Decline

Prior to the closure of the chapel in the 1980s, the size of the congregation had declined and the fabric of the building was deteriorating. In 1978 the decorative plaster ceiling was replaced with a suspended ceiling of acoustic tiles, with further repairs carried out under the Manpower Services Commission. During the course of these repairs, discussions took place about the future of the building and its dwindling congregation.[4] None of the ideas for developing the building came to fruition, and worship in the chapel ended in December 1985. Permission to demolish the building was refused because of its listed status. It was bought by a private individual in 1987, but the plan to convert it into a nightclub was declined. The building was acquired by the Bethesda Heritage Trust in 2000. After the Bethesda Heritage Trust failed to raise sufficient finance to continue worship, in 2002 it passed into the ownership of the Historic Chapels Trust, an organisation which aims to find community uses for the buildings in its care.[4] In 2003 the chapel was a finalist in the BBC's first Restoration series, where viewers decided on which listed building, that was in immediate need of remedial works, was to win a grant from Heritage Lottery Fund; it failed to win the prize.[1]

Restoration

The Historic Chapels Trust obtained an estimate for the restoration, which amounted to £2.5m. Unable to meet the full amount, the Trust decided to undertake the restoration in phases. The first phase was completed in September 2007 at a cost of nearly £900,000, which included weatherproofing and major works to the roof.[7] Of the money raised for this, £262,500 came from the Heritage Lottery Fund, £200,000 from English Heritage, £250,000 from Stoke-on-Trent City Council, and a further £20,000 was raised locally.[1] The second phase of restoration commenced in August 2010 and was completed a year later. The Trust spent £600,000 restoring the galleries, staircases and pulpits, replacing the organ and renovating the exterior ironwork. Funds are currently being raised for the final phase of restoration, which will include installation of a new heating and lighting system.[5]

The Historic Chapels Trust has set out a plan which identifies 27 potential uses for the building. These include concerts, weddings and civil partnerships, conferences and use as an exhibition space.[5]

Architecture

The brick chapel is built in an Italianate style with a stuccoed facade and a slate roof.[5] According to Nikolaus Pevsner, the Methodists chose this style of architecture "in order not to look Anglican."[8] Its ground floor is rusticated and has a single-storey portico, extending along the full length of the chapel frontage. This consists of a heavy cornice supported on pairs of fluted Corinthian columns. Over the portico, in the centre of the upper storey, is a Venetian window, with two sash windows on each side. At the summit of the frontage is a central pedimented gable.[6] On each side of this is a massive decorated cornice.[3] The building extends back for five bays, and at the rear is a shallow curved apse.[6] The rear of the building is built in Flemish bond brickwork.[6]

Immediately inside the entrance there is a vestibule, with stairs on either side leading up to the gallery. Inside the main body of the chapel is a continuous tiered gallery carried on cast iron columns.

Organ

The three-manual organ, with its baroque case, stands on the street-facing side of the gallery. The case originally housed an instrument built in 1864 by the Manchester organ builders Jardine and Co. The recently completed instrument was favourably reviewed in the London publication The Musical World.[9] In the 1950s it was enlarged, rearranged, and converted to pneumatic action. The metal pipework was stolen after the closure of the chapel,[10] and, as part of the restoration project discussed above, it was decided to bring in a replacement instrument. The one chosen was by the same maker and had become redundant after having been used in two churches in the Manchester area (Kersal Moor and Ordsall).[11]

Pulpit

Under the organ is an octagonal pulpit approached by two flights of stairs. The stairways to the pulpit have cast iron balustrades and hardwood handrails. On each side of the pulpit is a communion rail.[6]

Windows

The chapel has a number of stained glass windows. One depicts a design taken from The Light of the World, a painting by the Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt, and is situated to the left of the east aisle.[12] A second window dedicated to one Fannie Nuttall is located next to the right aisle, depicting the Sistine Madonna by Raphael.[12]

Bethesda

The name Bethesda comes from the Aramaic בית חסד/חסדא (beth ḥesda; "House of Mercy"). It originally referred to the Pool of Bethesda, a pool of water in Jerusalem reputed to have healing powers.[13][14] Bethesda was a popular name for chapels and meeting houses among Nonconformists;[14] Bethesda Chapels were built, for example, in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire,[15] Stroud, Gloucestershire,[16] and Rillington, Yorkshire.[17]

References

- 1 2 3 Restoration — Series 1: Bethesda Chapel, BBC, archived from the original on 13 December 2011, retrieved 17 June 2014

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins, J. G., ed. (1963), "The city of Stoke-on-Trent: Protestant Nonconformity", A History of the County of Stafford, University of London & History of Parliament Trust, vol. 8, pp. 276–307, retrieved 6 July 2010

- 1 2 Bethesda Methodist Chapel: Architecture, Friends of Bethesda, retrieved 7 July 2010

- 1 2 3 Bethesda Methodist Chapel: History, Friends of Bethesda, retrieved 7 July 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bethesda Methodist Chapel, Historic Chapels Trust, retrieved 6 July 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 Historic England, "Bethesda Methodist Chapel, Stoke-on-Trent (1195821)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 3 July 2013

- ↑ Bethesda Methodist Chapel: HCT's Proposals, Friends of Bethesda, retrieved 7 July 2010

- ↑ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Staffordshire. The Buildings of England. CT, USA: Yale University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780300096460.

- ↑ "New Organ for Bethesda Chapel, Hanley, Staffordshire". The Musical World. September 1864. Retrieved 8 June 2015. (accessed via RIPM, subscription required)

- ↑ "Staffordshire, Hanley: Bethesda Methodist Chapel, (Methodist New Connexion) [C01046]". National Pipe Organ Register. British Institute of Organ Studies. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ "Staffordshire, Hanley, Bethesda Methodist Chapel, (Methodist New Connexion) [E01283]". National Pipe Organ Register. British Institute of Organ Studies. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- 1 2 Leigh, J.; Anderson, J. H.; Booth, J. S. (2010). "Bethesda Methodist Chapel, Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent: A History and Guide". London, UK: Historic Chapels Trust: 16–19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Bauscher, Glenn David (April 2008). The Original Aramaic New Testament in Plain English. North Carolina: Lulu Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 9781435712898.

- 1 2 "Definition: Bethesda". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ Historic England, "Bethesda Methodist Church, Cheltenham (1104293)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 March 2015

- ↑ Historic England, "Bethesda Chapel, Uley (1171537)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 March 2015

- ↑ Historic England, "Bethesda Chapel, Rillington (1315779)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 March 2015