In real estate, betterment is the increased value of real property from causes other than investment made by the property owner.[1] It is, therefore, usually referred to as unearned increment or windfall gain.

When, for instance, a property is rezoned for higher-value uses, or nearby public improvements raise the value of a piece of private land, a property owner is "bettered" due to the actions of others. Because of this, capturing the value of betterment for the public through taxation or other means is a common policy approach.

Betterment in terms of property rights and the residual value model

Property rights and residual value

A property rights holder has a residual claim to income generated in the space over which they have exclusionary rights (“pay to use this space or I’ll exclude you from it”). But these rights are a limited Bundle of rights. They evolve as the law evolves, including zoning and planning law.

The value of private property rights is primarily determined by how much revenue can be generated above costs (excluding property rights costs) on a site at a particular location; that value of property rights value is residual value, just like in other assets like shares in company ownership, which are a claim on residual income. Whichever use of a site generates the largest residual income is its highest and best use.

The value of private property rights is affected by market conditions, location-specific features, fixed improvements, and the nature or extent of the property right. Investing in new fixed improvements, like buildings and earthworks, can add to the value of property because they remove a cost to gaining revenue (remember, property value is revenue minus costs needed to earn that revenue at that location). Their value becomes “attached” to the property as they cannot be separated physically or legally from the property right to a location.

However, the value of private property rights can also increase due to external factors rather than due to investments made by the property rights owners. This is betterment. For example, when the law changes the nature or extent of property rights, such as rezoning to provide additional development rights to property owners, this provides value to the property owner.

Where betterment comes from

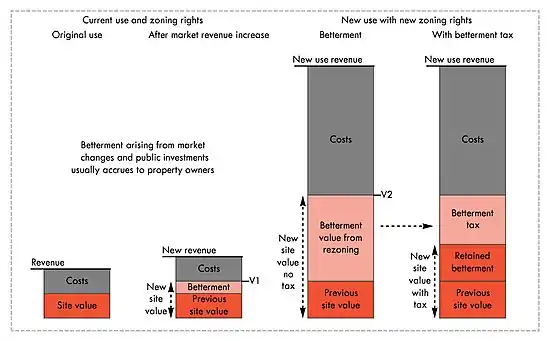

The below image shows how betterment arises conceptually, and also how a tax on betterment transfers this value that would otherwise accrue to private property owners to the public.[2]

The left column shows the value of the property rights at a site, such as agricultural or industrial land. That value is determined by the revenue that can be made from exclusively using that site, minus the costs involved in using it. The site value is the residual.

If the market value of the output being produced increases, such as the value of crops, or the value of industrial outputs, but all input costs remain the same, then the site value rises to reflect the higher residual value of production on that site.

This is shown in the second column. For example, if the rent of a residential dwelling rises, but the costs of operating that dwelling remain constant, the value of the home site increases. This change can be considered a windfall gain, and some of that gain is shared with the public where there is a land value, or property, tax system.

The third column shows what happens if there is a change in the nature or extent of the property rights through rezoning. For example, if the previous highest and best use of a site was industrial only because zoning laws prevented other higher residual uses such as residential or commercial at that location, then rezoning will change the highest and best use of the site and hence its value. The difference between the “before” site value (V1) and the new “after” site value (V2) is betterment.

The effect of a tax on betterment arising from rezoning is illustrated in the fourth column. A share of the betterment value is transferred from the private property owner to the public, reducing the private payoff from rezoning decisions, and increasing the public share of benefits.

Public capture of betterment

There are three common ways to capture betterment from rezoning for the public.

- A betterment levy or tax can divert from the owner of the property the betterment due to planning and zoning changes.

- Using a public agency to purchase unzoned and undeveloped land, then rezoning and investing in local infrastructure can ensure that all betterment from the rezoning and infrastructure investment is captured by the public.

- Auctioning or selling rights to develop to higher-value uses.

Australia

Australian Capital Territory (ACT)

The ACT has had a betterment tax in some form since 1971. Its incarnation is the Lease Variation Charge (LVC), which is payable upon an approved development application (though payment timing can be deferred for a period). In 2018-19 it raised $53 million in revenue.[3]

The ACT also captures rezoning betterment for the community by deploying a public agency to undertake all the greenfield land development. This means that the public captures 100% of the betterment from converting rural to urban uses. In 2019-20, $100 million of revenue was raised from this approach.[4]

Sydney

In 1969 a betterment levy of 30% In Sydney from 1970-74 a 30% rezoning betterment tax applied for the conversion of land from rural to urban uses. The tax payment was triggered by a sale or development approval. It raised, $17 million over its 4.5 years of operation.[1] The Sydney experience in the 1970s was short-lived only because of organised political pressure of landowners who no longer got windfall gains as the city grew.

Victoria

In its 2021 budget, the Victorian government proposed a windfall rezoning tax of 50% for the conversion of industrial to high density residential uses.[5]

England

In Housing, Town Planning Act 1909 granted local authorities the option, but not the obligation, to collect betterment and compensate "worsenment" due to planning changes. It was proposed that the entire increase in value due to the scheme be collected when the scheme was adopted, with calculation at that date, but an arbitrary 50% was adopted as a compromise, although some 1909-Act "progeny schemes" raised up to 80%.

In 1932 the percentage was increased to a permissible 75%, claimable within 12 months of the change, with payment deferrable until a change of use or disposition of the property (including a transfer or lease for 3+ years), when it was payable with interest.

Betterment provisions were removed in a 1948 change to the legislation.[6] They were again introduced in the Land Commission Act 1967 at a 40% rate, but were abolished in 1970.[7]

Colombia

In Colombia, a betterment levy (called contribución de valorización) has been applied since 1921. The model applied depends on the city. The "Bogotá model" of betterment levy reflects more a general tax to cover the cost of specific public works. In the "Medellín model", it's more a participation in the surplus value generated by public works.[8]

Brazil

Since the 1990s São Paulo had obligations for property developers to contribute a minimum of 50 percent of the incremental value created although in the UO Agua Branca, this minimum was established as 60 percent.

Issues with the practical determination of betterment values led to the implementation of Certificate of additional construction potential bonds (CEPACs), which are issued by the city and sold by auction in the São Paulo Stock Market Exchange (Bovespa).

"They give the bearer additional building rights such as a larger floor area ratio and footprint and the ability to change uses of the plot. Financially speaking, CEPACs are the economic compensation a developer gives the public administration in return for new building rights."[9]

Netherlands

Numerous other cities have variations on this "public purchase and rezone" approach. Public agencies acquiring major un- and under-developed sites prior to rezoning and master-planning for urban uses, then selling most of the up-zoned properties with new roads and infrastructure for private development. This allows public agencies to coordinated public infrastructure without acquiring private property with high value zoning rights and capture 100% of the betterment from zoning changes.[10]

References

- 1 2 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Betterment". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 831–832.

- ↑ Cameron K. Murray. "Explainer: Taxing rezoning windfalls (betterment)". Open Science Foundation. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ↑ "2018-19 Annual Report" (PDF). Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ "2019-20 Annual Report" (PDF). Suburban Land Agency, ACT Government. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ "Contributing A Fair Share For A Stronger Victoria". Premier of Victoria, The Hon Daniel Andrews. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ "Betterment & Worsenment: Balancing Public and Private Interests" (PDF). University of Queensland Law School. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ "Land Value Taxation: Betterment Taxation in England and the Potential for Change" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-20. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ↑ "Evaluación de la contribución de valorización en Colombia". Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ↑ "CEPACS: Certificates of Additional Construction Potential". Paulo Sandroni. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ Needham, Barrie (1997). "Land Policy in the Netherlands". Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie. 88 (3): 291–296. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.1997.tb01606.x. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

External links

The dictionary definition of betterment at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of betterment at Wiktionary