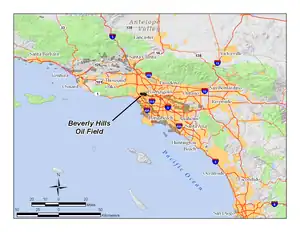

The Beverly Hills Oil Field is a large and currently active oil field underneath part of the US cities of Beverly Hills, California, and portions of the adjacent city of Los Angeles. Discovered in 1900, and with a cumulative production of over 150 million barrels of oil, it ranks 39th by size among California's oil fields, and is unusual for being a large, continuously productive field in an entirely urban setting. All drilling, pumping, and processing operations for the 97[1] currently active wells are done from within four large "drilling islands", visible on Pico and Olympic boulevards as large windowless buildings, from which wells slant diagonally into different parts of the producing formations, directly underneath the multimillion-dollar residences and commercial structures of one of the wealthiest cities in the United States. Annual production from the field was 1.09 million barrels in 2006, 966,000 barrels in 2007, and 874,000 in 2008, and the field retains approximately 11 million barrels of oil in reserve, as estimated by the California Department of Conservation.[1][2] The largest operators as of 2009 were independent oil companies Plains Exploration & Production and BreitBurn Energy.[3]

Setting

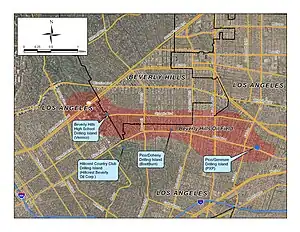

While the oil field is unusual for being entirely within the confines of a large city, it is but one of many in the Los Angeles basin which are now overbuilt by dense residential and commercial development. The field is long and narrow, about four miles (6 km) long by a half-mile to mile across. Its long axis is aligned in a generally east-west direction, extending from the vicinity of the intersection of Santa Monica Boulevard and Beverly Glen on the west, east along Pico Boulevard, past La Cienega and Fairfax Avenue, to around the intersection of Pico and Hauser. From north to south the field is much narrower, extending near the middle of the field from near Monte Mar Drive in Los Angeles to about two blocks north of Olympic Boulevard in Beverly Hills. The total productive area of the field, projected to ground surface, covers about 1,200 acres (4.9 km2).[4]

In most oil fields, wells are drilled at optimum spacing for petroleum extraction with the boreholes going straight down into the target formations. Since this method of field development is not possible in a large city with no open land, all the wells tapping into the Beverly Hills field are clustered into four drilling islands—oil production and processing facilities tightly packed into windowless, soundproofed buildings—so as to have a minimal impact on adjacent land uses. The westernmost of these buildings, containing wells and which accesses the designated West Area of the field, is on the grounds of Beverly Hills High School at the corner of Olympic Boulevard and Heath Avenue, just southeast of the baseball diamond. This facility also houses storage tanks, several oil-water separator units, a pump house, compressor house, and an office building.[5]

A facility similar to the one adjacent to Beverly Hills High School, operated by BreitBurn Energy, is north of Pico between Doheny Drive and Cardiff Ave. Yet another drilling island, the largest of the four, containing over fifty active wells and operated by Plains Exploration & Production, is north of Pico between Genesee Avenue and Spaulding Avenue. This drilling island also contains wells that angle northeast into the Salt Lake Oil Field. Within the boundary of the adjacent Cheviot Hills Oil Field, and on the grounds of the Hillcrest Country Club about 500 feet (150 m) south of the intersection of Pico Boulevard and Century Hill East, is a fourth, smaller drilling island, operated by Hillcrest Beverly Oil Corp. This small drilling island includes 12 active wells directionally drilled into the Beverly Hills Oil Field, as well as several others drilled into the Cheviot Hills Field.[6]

The operators of a fifth drilling island, located at the northern corner of Avenue of the Stars and Constellation Boulevard in Century City, finished abandoning it in 1990. Originally constructed in the 1950s on what was then an unused back lot of Twentieth Century Fox Studios, its production steadily declined in the 1970s, and by 1989 the last well was shut down. Land use changes and soaring real estate values contributed to its elimination.[7]

The city of Los Angeles handles all building permits and air permitting issues for the oil field.[8]

Geology

The field is a faulted anticlinal structure with oil trapped by a combination of structural and stratigraphic mechanisms. Bounding the field on the south is the Brentwood-Las Cienegas Fault, and the field ends on the west near the Santa Monica Fault Complex. The minimum depth to the larger deposits of profitably extractable oil varies from about 5600 to about 7,200 feet (2,200 m) below ground surface, or 5400 to 7,000 feet (2,100 m) below sea level (as the approximate elevation of this portion of the Los Angeles Basin is about 200 feet).[4]

The uppermost producing unit was the first to be discovered, and consists of oil-bearing structures called the Wolfskill Zone, within the Repetto Sands, a Pliocene-age feature principally in the western part of the field. Oil in these sands is mainly found in pinch-out structures, in which oil is trapped in more permeable sub-units within impermeable sands. Underneath this unit, separated by an unconformity, is the larger Modelo Formation, consisting of several sand units: the D/M Sands (the topmost), the Hauser Sand, around 4,500 feet (1,400 m) below sea level, and the Ogden Sand, around 7,200 feet (2,200 m) below sea level. Beneath the Ogden Sand is a nodular shale unit, also grouped with the Modelo; it contains no oil. Both the Ogden and the Hauser are richly productive, while a few oil-bearing pinch-outs are found in the D/M sand, which otherwise forms an impermeable cap to the Hauser.[4] The deepest unit in the field which is being pumped is a portion of the Ogden Sands in the East Area of the field, discovered in 1967, which is at an average depth of 10,800 feet (3,300 m).[9]

According to BreitBurn Energy, one of the two principal producers on the eastern part of the field, there were 600 million barrels of oil originally in place; since 111 million have been recovered, about 489 million remain. They do not state what percentage of that reserve is recoverable using current technologies.[10]

History, production, and operations

Oil was discovered in the northern Los Angeles basin in 1893, not far from the city center, and development of the Los Angeles City Oil Field was fast. By 1895, that field was producing over half of the oil in the state, and drillers began looking for even more new oil prospects around the basin, attempting to match the enormous finds taking place simultaneously just over the Tehachapis in Kern County.[11] In July 1900, W.W. Orcutt drilled into the Wolfskill zone of the Repetto Sands, about 2,500 feet (760 m) below ground surface, discovering the Beverly Hills Field.[4] While the oil was of reasonably good quality—it was light, with a high API gravity between 33 and 60, although with a high sulfur content—development was slow, since the Wolfskill find was relatively small, and other fields in the Los Angeles basin were growing almost as fast as operators could drill new wells.

The eastern portion of the field—known simply as the East Area—is the most productive, and is also the most recently discovered of all the major oil fields in the Los Angeles Basin, as it was not found until 1966. It reached its peak production quickly, within two years of discovery, reporting 11.8 million barrels for 1968.[9] In 1988, BreitBurn Energy bought a portion of the Beverly Hills Field, intending to apply modern mapping and secondary recovery technology to the mature oil field, as previous operators were moving out, in favor of easier prospects in less highly regulated environments.[12]

Field operators began using waterflooding in 1968 in several pools in the East Area (now operated by BreitBurn and Plains).[9] In this method, produced water is reinjected into the reservoir to increase pressure (as oil is pumped out, internal reservoir pressure naturally decreases, resulting in a reduced pumping rate; a common way to restore pumping rates is to reinject wastewater into the reservoir to restore the original reservoir pressure). Water reinjection is also a convenient means of wastewater disposal, which in an urban setting is a practical problem, as the volume of water pumped from the reservoir often exceeds that of crude oil; while oil fields in isolated areas often use large evaporation ponds for water disposal, that luxury is not available for crowded urban sites with higher environmental standards. For example, in 2008, the California Department of Conservation, Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) reported 882,953 barrels of oil produced from the field, but 8,732,941 barrels of water. Of this, 7,280,887 barrels were reinjected back into the reservoir.[13][14]

Since many of the residents of the area own the mineral rights to their properties, they are entitled to royalty payments from the oil produced from underneath their land. In 1975, there were 6,200 individuals getting such payments.[15]

Development of the field has not been without controversy. The drilling island adjacent to Beverly Hills High School occasioned a series of lawsuits in 2003, in which parents of students at the school, observing what they believed to be excess rates of certain cancers among those exposed to toxins emitted from the facility, attempted to have it shut down. Plaintiffs claimed that a "cluster" of 280 cancers—primarily Hodgkin's disease, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and thyroid cancer, recorded over a period of about 30 years—were caused by emissions of volatile organic compounds (including benzene and toluene) from the drilling island, currently hidden behind sound walls. Samples of air taken near the site by the South Coast Air Quality Management District (AQMD) showed nothing unusual, and the cases were thrown out in 2006 and 2007. The judge who dismissed the cases, Superior Court Judge Wendell Mortimer Jr. said that he was unpersuaded that the facility caused any harm, and also "found no evidence that the school district was aware of any danger."[16][17] Additionally, the University of Southern California Medical School stated that the particular cancers noted in the lawsuits are not known to be caused by exposure to petroleum and its byproducts.[18]

Notes

- 1 2 "Oil and Gas Statistics: 2007 Annual Report" (PDF). California Department of Conservation. December 31, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-12. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ↑ "2008 Preliminary Report of California Oil and Gas Production Statistics" (PDF). California Department of Conservation. January 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ↑ DOGGR database: well production sums

- 1 2 3 4 California Oil and Gas Fields. Sacramento: California Department of Conservation. 1998. pp. 46, 49. Archived from the original on 2010-01-02. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ Horowitz, p. 8.

- ↑ California Department of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources

- ↑ DOGGR 1990 Annual Report, p. 15–16.

- ↑ Mark T. Gamache and Paul L. Frost, Urban Development of Oil Fields in the Los Angeles Basin Area, 1983 to 2001. Publication No. TR52, California Department of Conservation. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 California Oil and Gas Fields. Sacramento: California Department of Conservation. 1998. p. 48. Archived from the original on 2010-01-02. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ Archived 2008-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Reinhard Suchsland, Geology and Production History of the East Beverly Hills Oil Field, Los Angeles Basin, California.

- ↑ "Oil History of California, DOGGR" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ↑ Megan Sever: "Urban Oil Drilling", GeoTimes

- ↑ DOGGR Beverly Hills Field production query.

- ↑ DOGGR Beverly Hills Field injection query.

- ↑ Erickson, R.C; Spaulding, A.O (2013). "Urban Oil Production and Subsidence Control - A Case History, Beverly Hills (East) Oilfield, California". Fall Meeting of the Society of Petroleum Engineers of AIME. doi:10.2118/5603-MS.

- ↑ "Beverly Hills schools dropped from lawsuit over campus oil well". Associated Press. March 23, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ↑ Kasindorf, Martin (April 28, 2003). "Lawyers calling Beverly Hills High a hazard". USA Today. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ↑ Jaroff, Leon (June 11, 2003). "Erin Brockovich's Junk Science". Time. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

References

- California Oil and Gas Fields, Volumes I, II and III. Vol. I (1998), Vol. II (1992), Vol. III (1982). California Department of Conservation, Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR). 1,472 pp. Beverly Hills Oil Field information pp. 46–50. PDF file available on CD from www.consrv.ca.gov. (As of August 2009, not available for download on their FTP site.)

- California Department of Conservation, Oil and Gas Statistics, Annual Report. December 31, 2006.

- California Department of Conservation, Oil and Gas Statistics, Annual Report. December 31, 2007.

- Horowitz, Joy. Parts per million: the poisoning of Beverly Hills High School. p. 8. Viking, 2007. ISBN 0-670-03798-2

External links

- Aerial photo in Google Maps showing the West Pico facility

- Chevron Corporation (then Standard Oil) brochure from the late 1960s, describing field operations and benefits to homeowners, including royalty payments

- School Fuel: Beverly Hills High's Tower Of Hope - illustrated article about the drilling island adjacent to Beverly Hills High School