| Big Rock Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: | |

Exposure of Big Rock Formation at Mesa la Jara, New Mexico | |

| Type | Formation |

| Unit of | Vadito Group |

| Underlies | Burned Mountain Formation |

| Overlies | Lower Vadito Group |

| Thickness | 70 m (230 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Metaconglomerate |

| Other | Quartzite |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 36°32′59″N 106°05′15″W / 36.5496°N 106.08744°W |

| Region | Tusas Mountains, New Mexico |

| Country | United States |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Big Rock (36°33′29″N 106°04′16″W / 36.558°N 106.071°W) |

| Named by | F. Barker |

| Year defined | 1958 |

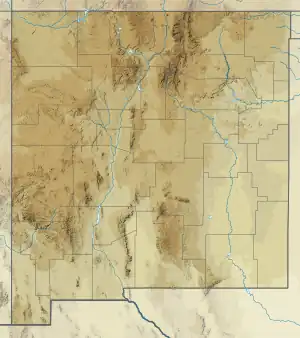

Big Rock Formation (the United States)  Big Rock Formation (New Mexico) | |

The Big Rock Formation is a formation that crops out in the Tusas Mountains of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology gives a maximum age for the formation of 1665 Mya, corresponding to the Statherian period.

Description

The Big Rock Formation consists of a lower conglomerate member with minor micaceous quartzite and an upper quartzite member. The conglomerate is a medium to dark gray quartz pebble metaconglomerate with minor quartzite beds, interpreted as braided alluvial deposits. The pebbles are mostly of light gray quartz but with some ferruginous chert. Pebble sizes are from 1 to 20 cm and the pebbles are systematically elongated. Crossbedding is pervasive.[1] Flattened felsic clasts may be metamorphosed pumice.[2] It is exposed in the central Tusas Mountains, where it is distinctive enough to be an important stratigraphic marker bed. Its thickness is typically 60 meters (200 feet).[3]

Detrital zircon geochronology yields a minimum age for the source regions of 1665 Mya, consistent with the formation being deposited in an extensional basin (the Pilar basin) opened during the transition from the Yavapai orogeny to the Mazatzal orogeny.[4]

Based on clast deformation, the formation has been compressed 55 percent during folding, while being extended 10 percent parallel to the strike and 65 percent parallel to the dip. This assumes the clasts were not imbricated in the original deposit.[5]

The Big Rock Formation lies above the undivided lower Vadito Group and below the Burned Mountain Formation. It was long thought to correlate with the Marquenas Formation,[3] but Marquenas Quartzite has been found via detrital zircon geochronology be much younger.[4]

The formation has been interpreted as a beach gravel[6] or as a high-energy fluvial deposit associated with the Pilar basin of the Yavapai orogeny.[4]

History of investigation

The unit was originally designated as the Big Rock conglomerate member of the Kiawa Mountain Formation by Fred Barker in 1958, during the mapping of the Las Tablas quadrangle.[1] It was designated as a formation within the Vadito Group by Bauer and Williams in their sweeping revision of northern New Mexico Precambrian stratigraphy in 1989.[3]

Footnotes

References

- Barker, Fred (1958). "Precambrian and Tertiary geology of Las Tablas quadrangle, New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Bulletin. 45.

- Bauer, Paul W.; Williams, Michael L. (August 1989). "Stratigraphic nomenclature ol proterozoic rocks, northern New Mexico-revisions, redefinitions, and formaliza" (PDF). New Mexico Geology. 11 (3). Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Gresens, Randall L. (1972). "Staurolite-quartzite bands in kyanite quartzite at Big Rock, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico ? A discussion". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 35 (3): 193–199. doi:10.1007/BF00371214.

- Jones, James V. III; Daniel, Christopher G.; Frei, Dirk; Thrane, Kristine (2011). "Revised regional correlations and tectonic implications of Paleoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic metasedimentary rocks in northern New Mexico, USA: New findings from detrital zircon studies of the Hondo Group, Vadito Group, and Marqueñas Formation". Geosphere. 7 (4): 974–991. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Simmons, Mary C.; Karlstrom, Karl E.; Williams, Michael W.; Larson, Toti E. (2011). "Quartz-kyanite pods in the Tusas Mountains, northern New Mexico: A sheared and metamorphosed fossil hydrothermal system in the Vadito Group metarhyolite" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 62: 359–378.