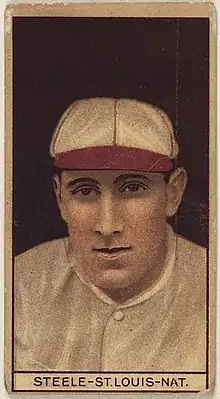

| Bill Steele | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: October 5, 1885 Milford, Pennsylvania | |

| Died: October 19, 1949 (aged 64) Overland, Missouri | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 10, 1910, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 1, 1914, for the Brooklyn Robins | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 37-43 |

| Earned run average | 4.02 |

| Strikeouts | 236 |

| Teams | |

| |

William Mitchell Steele (October 5, 1885 – October 19, 1949) was a pitcher in Major League Baseball (MLB). He pitched from 1910 to 1914 with the St. Louis Cardinals and Brooklyn Robins. Nicknamed "Big Bill", at 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m), he was one of the larger players of his era. His main pitch was a spitball.

Steele grew up in Milford, Pennsylvania. He began pitching at the professional level in 1909, and after winning 25 games for the Altoona Rams in 1910, he was signed by the Cardinals. Steele appeared in nine games with the team that year, then pitched a career-high 287+1⁄3 innings in 1911. He led the National League (NL) with 19 losses while posting a 3.73 earned run average (ERA). In 1912, Steele posted the worst ERA (4.69) among pitchers with enough innings to qualify for the MLB ERA title. He claimed in 1913 that he had purposefully not been trying as hard as he could have in 1912, and this impaired his relationship with the front office. Bothered by rheumatism the next couple of seasons, Steele found himself used mainly as a mopup reliever by 1914. Sold to the Robins later that year, he finished his MLB career with eight appearances in a Brooklyn uniform. Steele then played minor league baseball for a couple more seasons. A few years after he retired, he and his family moved to the St. Louis area, where he worked as a mechanic for Swift and Company and later as a maintenance man at an A&P warehouse. He was killed on October 19, 1949, when a streetcar ran into him.

Early life

William Mitchell Steele was born on October 5, 1885, in Milford, Pennsylvania. His parents, Maurice and Caroline ("Carrie"), were the children of Germans who had immigrated to New York. Maurice worked at an ice business, a sawmill, and a watch-case factory, also serving at times as a constable. On top of this, the Steeles owned a farm. Growing up, Bill helped tend the farm along with three of his siblings (a fourth died at birth).[1]

Steele started playing baseball in rural pastures around Milford. He played the positions of pitcher and outfielder for Milford's local team, which held games against local and semipro teams, including competition as notable as the New York Cuban Giants. A 1907 article in the Pike County Dispatch reported that Steele's pitches were "more of a puzzle than ever with his shoots, drops and the ‘spit ball’ which he has thoroughly mastered."[1]

Baseball career

Altoona (1909-10)

By 1909, Steele was pitching professionally for the Altoona Mountaineers of the Class B Tri-State League, though his career nearly came to a premature end. Early in the year, Steele was riding a streetcar and grabbed a sand lever on the vehicle. Not properly insulated, the lever ""shocked [Steele] almost to insensibility," and he "narrowly escaped being electrocuted" according to a local newspaper.[1]

Steele won his first eight starts for Altoona and completed 37 of 39 games he started for the Mountaineers. In July, he started both games of a doubleheader against the Trenton Tigers, throwing shutouts in both and driving in the winning run in the 10th inning of the second game. He finished the year tied for the league lead in losses (21), but his 19 wins were tied for fourth in the league. Steele pitched 359+1⁄3 innings.[1]

Altoona became the Rams in 1910, and Steele became the best pitcher in their league. Major League Baseball (MLB) teams began scouting him, and in August, Steele's contract was purchased for $3,000 by the St. Louis Cardinals of the National League (NL). Roger Bresnahan, the team's manager, and Stanley Robison, the team's owner, had both been impressed when they came to watch him pitch. Steele completed 29 of 30 starts for Altoona, led the league with 25 wins, and helped the Rams become league champions. The "big ranky side-armer … looks like a finished product," opined Jim Nasium, a Philadelphia reporter.[1]

St. Louis Cardinals (1910-14)

1910

After the minor league season, Steele joined the Cardinals in September. St. Louis was in the midst of a losing season; the ballclub would finish with a 63–90 record.[2] In his September 10 debut, facing the Cincinnati Reds at the Palace of the Fans, Steele allowed five runs in the first inning but settled down after that, allowing seven runs in a complete game and contributing three hits, one of which was a triple, in St. Louis's 14–7 victory. He completed all eight of his starts that year and won four of his first five games, giving Cardinal fans something to cheer about in the midst of a seventh-place season.[1] In nine games (eight starts) his rookie year, Steele had a 4–4 record, a 3.27 ERA, 25 strikeouts, 24 walks, and 71 hits allowed in 71+2⁄3 innings pitched.[3]

1911

Deciding that the Cardinals needed a change of personnel, Bresnahan got rid of five of the Cardinal pitchers from the 1910 season; Steele was one of the only ones who remained on the roster through 1911.[2] The St. Louis Post-Dispatch said "[I]f Bresnahan’s team is to climb this year, it will be because the pitching is improved over the 1910 brand..." citing Steele as an important factor in the club's 1911 fortunes.[1] Steele struggled in his first two starts of the season, then had a ball hit off of his pitching arm during batting practice and missed two weeks of the season. He had just a 3–9 record through June 7, and St. Louis reporters noted that a lack of Cardinal scoring, occasional poor innings, and late-game struggles led to his lack of wins.[1]

June 11 marked a turning point in Steele's season. After giving up four runs in the first inning to the Boston Rustlers, Steele pitched scoreless ball for the rest of the game. The Cardinals won 5–4, a victory that moved them into fourth place in the league after a rough start to the season. The victory was the first in a span of 10 decisions lasting through July 19, where Steele would lose only once. Teammate Miller Huggins thought he did "excellent work" on the mound during this time.[1] He gave up six runs but got the win in a complete game, 8–6 victory over the Rustlers on July 13 that left the Cardinals just two games out of first place in the NL.[1] After July 19, his pitching became less consistent, and he won only two of his final nine decisions. His victory over the Philadelphia Phillies on August 17 is notable for being the only shutout of his career; Steele gave up just five hits in the game.[1] Steele finished the season having appeared in 43 games, 34 of which were starts, 23 of which he completed. He posted a 3.73 ERA in a career-high 287+1⁄3 innings and had an 18–19 record, tying Earl Moore of the Phillies for the NL lead in losses.[1] With a 75–74 record, the Cardinals finished in fifth place in the NL.[1]

1912

An arm injury suffered during 1912 spring training contributed to early-season struggles by Steele. With a 3–7 record and an ERA of almost 6.00 in late June, Steele was moved to the bullpen after a June 18 start. He also served poorly in this role and was given the chance to start again on June 29.[1] Facing the Reds, he "rose heroic, like some grand old monolith by the River Nile" according to the St. Louis Star and Times as he held Cincinnati to seven hits and contributed a triple with the bases loaded in the 7–2 victory.[1][4] This instigated the best set of games Steele ever pitched, as he won six of seven decisions and posted a 1.95 ERA through August 3.[1] In the last of those, on August 3, Steele held the Phillies to five runs (three earned) in a complete-game, 7–5 victory, improving his record for the season to 9–8.[5] However, he did not win another game all season, going 0–5 the rest of the way.[6] In 40 games (25 starts), he had a 9–13 record, 67 strikeouts, 66 walks, and 245 hits allowed in 194 innings pitched, getting "hit hard" according to baseball historian Frank Russo.[3][2] Steele's 4.69 ERA, as well as his 11.4 hits allowed per nine innings pitched, were the worst totals among pitchers who threw enough innings to qualify for the MLB ERA title.[1]

1913

In late February 1913, Steele criticized Bresnahan, who had been fired as manager the previous August. Steele accused him of not treating the players fairly, going on to say that he deliberately tried not to pitch as well because of this. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat in response suggested that Bresnahan kept Steele with the team when the pitcher did not deserve it, adding "Steele is not deserving of the least bit of sympathy from anyone."[1] Unpopular with the Cardinals' front office as a result, Steele's troubles increased when he came down with rheumatism in his right hip during spring training. He left the team in the middle of March, and the Cardinals did not know where he was when the season began. They kept him officially on the roster, however, because they needed pitchers. Steele rejoined the team a week into the season and "prolonged his big-league career," according to the Post-Dispatch, by holding Pittsburgh to one run and three hits on April 23 in a 3–1 victory.[1] Despite the win, Steele was bothered by his rheumatism, as he limped on the field and had difficulty running to first base. In May, he was removed from games before the end of the third inning in half of his six starts.[1] After that, he was mainly used as a mopup reliever.[2] His last game of 1913 came on July 9, after which he did not pitch again, due either to complications with the rheumatism or a dislocated hip. He left the team (with its permission) in July to return to Milford and get married.[1][7] In 12 games (nine starts), he had a 4–4 record, a 5.00 ERA, 10 strikeouts, 18 walks, and 58 hits allowed in 54 innings.[3] The Post-Dispatch labelled his season a "complete failure."[8] He was not the only Cardinal to struggle, as last-place St. Louis had the highest team ERA in the NL.[1]

1914

At spring training in 1914, Steele said that he believed he could win at least 25 games, but he again served in a mopup role once the regular season began.[2][9] He did not get along with Huggins, who had succeeded Bresnahan as manager. On August 7, Steele's contract was sold to the Brooklyn Robins.[1] Steele had only appeared in 17 games (two starts) thus far, posting a 1–2 record, a 2.70 ERA, 16 strikeouts, seven walks, and 55 hits allowed in 53+1⁄3 innings.[3]

Brooklyn Robins (1914)

With Brooklyn, Steele made eight appearances, only one of which was a start.[3] He won one game for the Robins, giving up one run in 3+2⁄3 innings in a 9–6 triumph over Cincinnati in the first game of a doubleheader.[10][11] In his last game of the year, on October 1, he entered in the ninth inning with Brooklyn leading the Phillies 7–6 and gave up three runs, taking the loss as Philadelphia triumphed 9–7.[10][12] Those were his only decisions with Brooklyn; he had a 5.51 ERA, struck out three batters, walked seven, and gave up 17 hits in 16+1⁄3 innings. In 25 games (three starts) between both teams, he had a 2–3 record, a 3.36 ERA, 19 strikeouts, 14 walks, and 72 hits allowed in 69+2⁄3 innings.[3]

Later career

The Robins optioned Steele to the Newark Indians of the Class AA International League after the 1914 season, but he was released without having played a game for them. The Syracuse Stars of the Class B New York State League picked him up for 1915. He made six appearances for the franchise, posting a 1–3 record.[13] The team released him after two weeks because he was not in as good physical shape as they had hoped he would be.[14] Steele then played for the Gettysburg Ponies of the Class D Blue Ridge League in 1916, also playing some local and semipro baseball around Milford before retiring.[1][2] In 129 major league games (79 starts), he had a 37–43 record, a 4.02 ERA, 236 strikeouts, 235 walks, and 733 hits allowed in 676+2⁄3 innings.[2][3]

Description and pitching style

When Steele made his debut on September 10, 1910, reporter Jack Ryder called him a "large and ferocious gentleman, with baleful ire in his amps and a curveball in his capacious mitt."[1] His eyes were blue, his hair was black, and he had a very squarish jaw. High cheekbones accented how long his face was. At 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m), he was one of the bigger players at that time.[1] His nickname was "Big Bill".[2] He often weighed nearly 200 pounds (91 kg), but this could change during the summer. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, "[T]he hot weather during the middle of the season sets him back a great deal and peels off too much flesh making him go stale and weakening him."[1] He relied mainly on the spitball but also threw a fastball and curveball. According to the Altoona Tribune in 1910, Steele could "make the spitter break any old way he pleases. Some times it goes over with a slide shoot; other times it drops a foot."[15]

Personal life

Steele met Ann Farr Doyle, a St. Louis resident, in early 1912. They were married in 1913 and had one son, Bernard, who would be born six years later.[1] Bernard played three years of minor league baseball in the 1940s, interrupted by a four-year service in the military during World War II.[1] A first baseman, he batted over .300 in his career, though he never played above the Class B level.[16] The Steeles lived in Milford until several years after Bill had retired; they then moved to 8275 Albin Street in Overland, Missouri, a St. Louis suburb. Swift and Company employed him as a mechanic, and he later worked for A&P as a maintenance man at one of their warehouses. As a side business, he raised New Zealand rabbits, which he sold to local hospitals so they could use them for experiments. Ann was the owner of a confectionery store until her death in 1945.[1]

Death

On October 19, 1949, a rainy evening, Steele was hit by a streetcar in Overland, just two blocks from his house. Taken to St. Louis County Hospital, he was declared dead when the ambulance arrived.[1][2] Initially, the coroner declared that Steele's death was a homicide. Walter F. Hibler, the streetcar operator, refused to testify, and no other witnesses to the death were found. Thus, Hibler was never charged with any wrongdoing.[2] Steele was buried in St. Louis's Memorial Park Cemetery, Section 1, Lot 373.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Wolf, Gregory H. "Bill Steele". SABR. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Russo, Frank (2014). The Cooperstown Chronicles: Baseball's Colorful Characters, Unusual Lives, and Strange Demises. New York: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 229–31. ISBN 978-1-4422-3639-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Bill Steele Stats". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ↑ "St. Louis Cardinals at Cincinnati Reds Box Score, June 29, 1912". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "St. Louis Cardinals at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score, August 3, 1912". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Bill Steele 1912 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Bill Steele 1913 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Weak Battery Is Cardinal Alibi for 1913," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 2, 1913. p. 6.

- ↑ "Big Bill Steele, Weighing 196, Is Ready to Twirl," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 16, 1914. p. 10.

- 1 2 "Bill Steele 1914 Pitching Gamelogs". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Cincinnati Reds at Brooklyn Robins Box Score, September 21, 1914". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Robins at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score, October 1, 1914". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Bill Steele Minor League Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Diamond Briefs," Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), June 12, 1915. p. 18.

- ↑ "Big Bill Steele Has Made Good," Altoona Tribune, September 27, 1910. p. 10.

- ↑ "Bernard Steele Minor Leagues Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors)