A Biomolecular Gradient is established by a difference in the concentration of molecules in a biological system such as individual cells, groups of cells, or an entire organism. A biomolecular gradient can exist intracellularly (within a cell) or extracellularly (between groups of cells). The purposes of such gradients in biological systems vary, but include chemotaxis and functions in development. These types of gradients play a role in many different types of signaling as well as recently being implicated in cancer metastasis.

Development

Cells themselves can create biomolecular gradients by releasing signaling molecules that diffuse outwardly. These gradients are critical for cellular identity and cell relocation. Similarly, the gradients produced by cells may influence cellular fate by their temporal and spatial characteristics. In certain organisms, the choice of cell fate can be determined by a gradient, a binary choice, or through a relay of molecules released by a cell.[1] If cell fate is binary, the identity of the cell is influenced by the presence or absence of a signaling molecule; consequently, these signals can also induce cell fate acting in a relay.[1] The relay functions by the source cell releasing a signaling molecule into the environment. Adjacent cells possessing similar cell identities respond to these signals and can release different signaling molecules to cells in their surrounding area, promoting additional new cell fates. This process continues to all cells in the developing organism. In contrast, a signal can act in a gradient, which induces a specific cell fate as a function of the concentration of the molecule in the gradient. These types of molecules are known as morphogens.

An example of this phenomenon is observed in the neural tube with varying concentrations of the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) protein.[1] Shh is characterized as a morphogen and possesses spatial and temporal characteristics that make it well suited for study.

Cancer

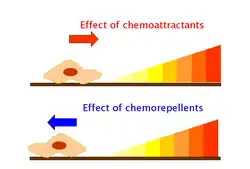

Biomolecular gradients have been shown to facilitate the invasion of cancer cells into different types of tissues in the body. Cancer metastasis is thought to be directly coupled to growth factor gradients that facilitate chemotaxis of cancer promoter factors. These chemoattractants promote tumour angiogenesis, namely increased blood flow to tissues allowing the cancer to thrive in different areas of the body.[2] Therefore, this pathway allows for the movement of tumour-promoting molecules toward healthy tissues in the body.[2][3] Further study is required to quantify pathways involved in the above response and may provide insight into more effective treatment for cancer patients.

Signaling

In a similar way, biomolecular gradients can function as signal antagonists that have the potential to drastically affect the cell's characteristics and in turn, the organism's response. This includes allowing the cell to distinguish its orientation or shift the barrier of cell differentiation in a group of cells. For instance, such mechanisms can be used to help the body defend against infection. Specifically, the afflicted area of the body acts as an attractant through ligand-receptor binding. This can occur through the polarity that is established by signal antagonists. In addition, this type of ligand-receptor interaction can lead to a signal cascade that trigger mitosis. A type of gradient molecule that accomplishes the aforementioned mechanism is Pom1.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 Harvey Lodish; Arnold Berk; S Lawrence Zipursky; Paul Matsudaira; David Baltimore; James Darnell (2008). Molecular Cell Biology. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-1-4292-0314-2.

- 1 2 Eccles SA (2005). "Targeting key steps in metastatic tumour progression". Curr Opin Genet Dev. 15 (1): 77–86. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.001. PMID 15661537.

- ↑ Keenan , Thomas M.; Albert Folch (2008). "Biomolecular gradients in cell culture systems". Lab Chip. 8 (1): 34–57. doi:10.1039/b711887b. PMC 3848882. PMID 18094760.

- ↑ Moseley, J.B.; Mayeux, A.; Paoletti, A.; Nurse, P. (2009). "A spatial gradient coordinates cell size and mitotic entry in fission yeast". Nature. 459 (7248): 857–861. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..857M. doi:10.1038/nature08074. PMID 19474789. S2CID 4330336.