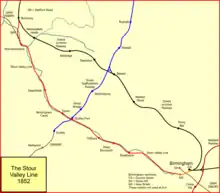

The Stour Valley Line is the present-day name given to the railway line between Birmingham and Wolverhampton, in England. It was authorised as the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Stour Valley Railway in 1836; the title was often shortened to the Stour Valley Railway.

The line opened in 1852, and the line is now the main line between those places. Associated with its construction was the building of the major passenger station that was later named New Street station, and also lines in tunnel each side of the station, connecting to the existing routes. The station was opened in 1854.

Before completion, the Company became controlled by the London and North Western Railway, which used dubious methods to harm competitor railways that were to be dependent on its completion.

The line was electrified in 1966 and now forms part of the Rugby–Birmingham–Stafford line, an important and very heavily used part of the railway network.

Origins

Birmingham's first main railway passenger terminal was Curzon Street station; it opened in 1838, although it was not given that name until 1852; at first it was simply the Birmingham station. The Grand Junction Railway opened to a temporary station at Vauxhall on 4 July 1837, approaching by curving round the north and north-west of the city[note 1] by way of Bescot and Aston.[1]

The London and Birmingham Railway opened to Curzon Street station from the south on 9 April 1838, completing its line to London on 24 June 1838. Through communication between London and Lancashire was achieved.[2]

The London and Birmingham Railway and the Grand Junction Railway were not always harmonious allies, and the L&BR courted alternative means of connecting with the industries of Lancashire. However, on 1 January 1846 they, and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway, amalgamated to form the London and North Western Railway.[3]

Birmingham was a major centre of industry and the workshops and manufactories of the district proliferated. The L&BR and the GJR had been planned as inter-city railways, and numerous locations that had gained in importance now demanded rail connection. The GJR route passed more than a mile from Wolverhampton, although there was a Wolverhampton station. So it was that the LNWR projected a direct line between Birmingham and Wolverhampton.[note 2][4]

Promoted in Parliament

In the 1846 session of Parliament, the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Stour Valley Railway was promoted. Its concept had originally included a branch towards Stourbridge; this was now omitted, but the reference to the Stour in the title remained. In fact the company was colloquially referred to as the Stour Valley Railway.

The route was to run between a new central station at Birmingham, and Wolverhampton, joining the Grand Junction Railway at Bushbury, north of Wolverhampton. The line was to start in central Birmingham and run broadly north-west, following the Birmingham Canal, which had already attracted much industry to adjacent areas. This meant avoiding the Grand Junction Railway's sweep through Aston, and instead cutting through the high ground in central Birmingham. There was to be a Dudley branch, though this was not built in the form originally authorised.[4]

There were sixteen railways proposed in the immediate area in the 1846 session, and there was much controversy over which of them should be authorised. There was a strong body of opinion that only one line between Birmingham and Wolverhampton was justified. As well as the Stour Valley Railway, two other lines between Birmingham and Wolverhampton were proposed in the same session: the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway, taking a more northerly route, and joining the (proposed) Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway at Priestfield; and the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway.

During the Parliamentary process the S&BR was induced to omit the section of its line south of Wolverhampton, taking instead a one-quarter share in the Stour Valley Railway; the LNWR had a quarter, as did the Birmingham Canal; private investors collectively took the other quarter.

Finally, despite the earlier presumption that only one connecting line was needed, both the Stour Valley Railway and the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway were authorised, on 3 August 1846.[5][6][7][8]

New Street station

The Stour Valley Railway would need a connection at the Birmingham end; this was authorised separately after considerable debate over the preferred site; opinion at first was that there would only be one main station. The station selected was what became New Street station, although that name was not used at first. It too was authorised on 3 August 1846, by the London and Birmingham Railway (Birmingham Extension) Act, which included nearly a mile of route from near Curzon Street, as well as the new station. The authorised capital was £35,000.[9][3][10]

Construction of the Stour Valley Line

So the Stour Valley Line was authorised, with the LNWR, the Birmingham Canal and the S&BR having large holdings. However an Act of 1846 gave the LNWR control of the Birmingham Canal Navigation company's system, so that the LNWR at once became the majority shareholder of the Stour Valley Railway. A further Act of 1847 permitted the LNWR to lease the (unbuilt) Stour Valley Line.[7]

The LNWR embarked on a prolonged and underhand attack on the S&BR, which it saw as a competing line for Lancashire and Cheshire traffic that the LNWR wished to have exclusively. It purposely delayed completing the line, in order to disadvantage the S&BR, which it now saw as a competitor for traffic for the north west. The S&BR had opened its line as far as Wolverhampton on 12 November 1849, but was unable to get access to Birmingham.[11]

Perkins wrote in 1952, referring to the Shrewsbury and Birmingham and the Shrewsbury and Chester companies:

[The LNWR] became the bitter enemy of both of the smaller systems, and strove to crush them by every means in its power. The story is sordid and remarkable, and it seems almost incredible that a great public institution should have descended to such paltry devices to injure or destroy its competitors.[8]

The Stour Valley line was practically complete in 1851, but the LNWR made no attempt to finalise the work or prepare it for opening. In response to an application to Parliament by the S&BR, the LNWR announced that the Stour Valley Railway was ready for opening by 1 December 1852, but the LNWR refused the S&BR access, on the grounds that the S&BR had announced its intention to amalgamate with the GWR. It had not actually done so, merely announced the intention, but this gave the LNWR the opportunity to prevaricate.

When judgment in Chancery was found against the LNWR, it refused to open the line to the S&BR, stating that it would be unsafe, as certain safety undertakings had not been formalised by the S&BR. The latter company then announced its intention of running a train anyway, on 1 December 1851. However the running powers held by the S&BR were for the Stour Valley line, which did not include entry to New Street station, which was part of a separate construction, and the LNWR physically obstructed the running of the train.[12][13][8]

The S&BR threatened a parliamentary bill to resolve the matter, and in February 1852 the LNWR opened the Stour Valley Railway to its own goods trains, and to passenger trains on 1 July 1852. Still the LNWR found reasons to exclude the running of S&BR trains, and it was only on 4 February 1854 that this usage started.[12][8]

Opening of the Birmingham station

The station was opened on 1 June 1854. The Midland Railway had been using Curzon Street and that company transferred its trains to the new station on 1 July 1854.[10]

On 14 November 1854 the Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway opened for traffic. This was a rival scheme in GWR hands, and the S&BR, now amalgamated with the GWR, transferred its trains to the friendly line, which used the GWR stations in both Wolverhampton and Birmingham.

The Birmingham station was known at first by the title Navigation Street Station.[14] Some years before this the Midland Railway and the LNWR had both given guarantees of dividend to the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway. In time the B&GR company was absorbed by the Midland Railway, and the LNWR guarantee remained as that company's obligation. On the opening of New Street station, an agreement was reached that the guarantee from the LNWR would be cancelled, and in return the Midland Railway was given access to New Street station. (It had been using Curzon Street station.)[14]

After opening

The allegiance of the two lines between Birmingham and Wolverhampton was entirely polarised, the Stour Valley Line being in the LNWR group and the BW&DR being a Great Western Railway line. Both had been formally leased or absorbed.

The Stour Valley Line became an important trunk route, but it also served numerous communities and industrial centres in its short length. As Birmingham itself grew in importance, and as the residential districts and neighbouring towns grew in prosperity, the suburban traffic using New Street station expanded considerably.

New Street Station widening

The approach to Birmingham New Street station from the east became very congested, with the LNWR's own main line traffic, supplemented by that from the Aston lines, as well as the Midland Railway's use of the station. A scheme for widening the approaches was undertaken at the end of the nineteenth century, duplicating the tunnel section and diverting the Midland lines from Derby and Gloucester (via Camp Hill). This work was completed in May 1896.[14]

The Midland Railway had their own part of New Street station from 8 February 1885, and the entire station was made joint between the LNWR and the Midland Railway from 1 April 1897.[15]

After 1923

Most of the main line railway companies of Great Britain were "grouped" following the Railways Act 1921, into one or other of four new large companies. The LNWR and the Midland Railway were constituents of the new London, Midland and Scottish Railway (the LMS), which from 1923 operated the Stour Valley Line and New Street station. In 1948 the railways were nationalised, following the Transport Act 1947 and British Railways were the new owner.

Electrification and modernisation

In the 1960s a major scheme of modernisation was undertaken on British Railways. Part of the scheme was the electrification at 25 kV overhead, 50 Hz, of the West Coast Main Line and certain branches. The main line itself came first, but electrification on the Rugby – Coventry – Birmingham – Wolverhampton – Stafford route followed. On 6 December 1966 the Birmingham – Wolverhampton section was inaugurated. The Grand Junction route via Bescot had become important for freight, and as a diversionary route for through passenger services, and it too was electrified: Bescot – Bushbury – Stafford was opened to electric trains on 24 January 1966, and Stechford - Bescot on 15 August 1966. A major modernisation of Birmingham New Street station was undertaken as part of the work.[16]

In the 1960s a number of branch lines had been closed as road-based passenger transport, and private car ownership, increased. It was considered useful to have an intermediate passenger railhead without entering the centres of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, and Oldbury station was selected for development. It was retitled Sandwell and Dudley, and opened on 14 May 1994. Selected main line trains called there.[17]

The original connection between the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway and the LNWR route at Wolverhampton had been closed in 1859, when the S&BR was given a better route over the GWR line. In 1966 it was reopened for the electrification, giving access for Shrewsbury trains to Wolverhampton High Level station, and electric train access to the important carriage sidings at Oxley, on the S&BR line.[18]

New Street station in the twenty-first century

The 1960s modernisation of Birmingham New Street station was considered by many to be unsatisfactory; the platform areas were dark and cold, and access to the platforms was congested. In 2006 Network Rail a regeneration scheme was announced, and work started in 2010. The shopping area above the station was extended and upgraded, and re-opened with the title Grand Central. It was completed in 2015. The new concourse is three times larger than the former, and is enclosed by a large atrium, allowing natural light throughout the station.[19]

The present day

Electrification in the 1960s meant concentration of all through passenger traffic on the Stour Valley route; most freight continued to use the Grand Junction Railway route via Bescot. There is a heavy passenger service on the Stour Valley line; twelve passenger trains are indicated in the Network Rail journey planner from Birmingham New Street to Wolverhampton in the hour from 11:00 to 11:59 on a weekday in June 2019.

Location list

.png.webp)

- Bushbury; station on Grand Junction Railway; opened 2 August 1852; closed 1 May 1912;

- Wolverhampton; opened 1 July 1852; sometimes called Mill Street; later called High Level; still open; divergence of line to Walsall 1872 -;

- Monmore Green; opened 1 December 1863; closed 1 January 1917;

- Ettingshall Road; opened 1 July 1852; closed 15 June 1964;

- Deepfields and Coseley; opened 1 July 1852; closed 10 March 1902;

- Coseley; opened 10 March 1902; still open;

- Spur diverged to OW≀ 1853 – 1983;

- Bloomfield Junction; diverging line to Wednesbury, South Staffordshire Railway 1863 – 1981;

- Tipton Junction; converging line from Wednesbury 1883 – 1980;

- Tipton; opened 1 July 1852; renamed Tipton Owen Street 1953 – 1968; still open;

- Dudley Port; opened 1 May 1850; renamed Dudley Port Low Level after opening of GWR line; closed 6 July 1964; converging spur from SSR line 1854 – 1964;

- Albion; opened 1 May 1853; closed 1 February 1960;

- Oldbury and Bromford Lane; opened 1 July 1852; renamed Sandwell & Dudley 1984; still open;

- Spon Lane; opened 1 July 1852; closed 15 June 1964;

- Smethwick Galton Bridge; opened September 1995 (replacing Smethwick West on Stourbridge line);

- Galton Junction; convergence of line from Stourbridge 1867 -;

- Smethwick; opened 1 July 1852; renamed Smethwick Rolfe Street 1963; still open;

- Soho; opened May 1853; relocated 1884 – 1887; closed 23 May 1949;

- Soap Works Junction; divergence of Soho connecting line;

- Winson Green Junction; convergence of Soho connecting line;

- Soho TMD: accessed between the above two junctions.

- Winson Green; opened 1 November 1876; closed 16 September 1957;

- Harborne Junction; convergence of line from Harborne 1874 – 1963;

- Monument Lane; opened July 1854; renamed Edgbaston soon after opening; renamed Monument Lane 1874; relocated 1886; closed 17 November 1958;

- Birmingham; temporary platform at western end for Stour Valley trains opened 1 July 1852; full station opened 1 June 1854; later renamed Birmingham New Street; still open;

- Proof House Junction; convergence of Curzon Street line.

Notes

References

- ↑ Rex Christiansen, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 7: the West Midlands, David & Charles Publishers, Newton Abbot, 1973, 0 7110 6093 0, page 30

- ↑ Christiansen, page 37

- 1 2 Ernest F Carter, An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles, Cassell, London, 1959, page 115

- 1 2 Christiansen, page 103

- ↑ Donald J Grant, Directory of the Railway Companies of Great Britain, Matador Publishers, Kibworth Beauchamp, 2017, ISBN 978 1785893 537, page 35, pages 48 and 49

- ↑ Carter, page 116

- 1 2 M C Reed, The London & North Western Railway: A History, Atlantic Transport Publishers, Penryn, 1996, ISBN 0 906899 66 4, page 43

- 1 2 3 4 T R Perkins, The Railways of Wolverhampton: I: The Stour Valley and the Shrewsbury Lines, in Railway Magazine, July 1952

- ↑ Grant, page 35

- 1 2 Christiansen, pages 41 to 43

- ↑ Christiansen, pages 80, 82 to 84

- 1 2 Christiansen, pages 104 to 106

- ↑ Reed, page 63

- 1 2 3 S M Philip, New Street Station, Birmingham, in the Railway Magazine, April 1900

- ↑ Michael Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England, Scotland and Wales: A Chronology, the Railway and Canal Historical Society, Richmond, Surrey, 2002

- ↑ J C Gillham, The Age of the Electric Train, Ian Allan Publishing, Shepperton, 1988, ISBN 0 7110 1392 6, page 169

- ↑ Gillham, page 170

- ↑ Rex Christiansen, Forgotten Railways: volume 10: the West Midlands, David St John Thomas, Newton Abbot, 1985, ISBN 0 946537 01 1, page 40

- ↑ Network Rail, New Street has seen significant changes in its history, at https://www.networkrail.co.uk/who-we-are/our-history/iconic-infrastructure/the-history-of-birmingham-new-street-station/