The persecution of Jews during the Black Death consisted of a series of violent mass attacks and massacres. Jewish communities were often blamed for outbreaks of the Black Death in Europe. From 1348-1351, acts of violence were committed in Toulon, Barcelona, Erfurt, Basel, Frankfurt, Strasbourg and elsewhere. The persecutions led to a large migration of Jews to Jagiellonian Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. There are very few Jewish sources on Jewish massacres during the Plague.[1]

Background

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

The official policy of the Church, which was reasoned in part because Jesus was Jewish, was to protect Jews.[2] In practice, however, Jews were frequently the targets of Christian loathing.[3] As the plague swept across Europe in the mid-14th century and annihilated nearly half the population, people had little scientific understanding of disease and were looking for an explanation.

Jews were frequently used as scapegoats and false accusations which stated that they had caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells were circulated.[4][5][6] That is likely because they were less affected than the other people[7] since many Jews chose not to use the common wells which were located in towns and cities.[3] Additionally, Jews were sometimes coerced to confess to poisoning wells through torture.[3]

Persecutions and massacres

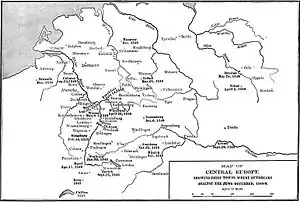

The first massacre directly related to the plague took place in April 1348 in Toulon, where the Jewish quarter was sacked, and forty Jews were murdered in their homes. Shortly afterward, violence broke out in Barcelona and other Catalan cities.[8] In 1349, massacres and persecutions spread across Europe, including the Erfurt massacre, the Zürich massacre, the Basel massacre, and massacres in Aragon and Flanders.[9][10] Around 2,000 Jews were burnt alive on 14 February 1349 in the "Valentine's Day" Strasbourg massacre, where the plague had not yet affected the city. While the ashes smouldered, Christian residents of Strasbourg sifted through and collected the valuable possessions of Jews that were not burnt by the fires.[11][12] The following September, 330 Jews were burned alive in the Kyburg Castle, east of Zürich.[13] Many hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed in this period. Within the 510 Jewish communities destroyed in this period, some members killed themselves to avoid the persecutions.[14]

In the spring of 1349, the Jewish community in Frankfurt am Main was annihilated. That was followed by the destruction of Jewish communities in Mainz and Cologne. The 3,000-strong Jewish population of Mainz initially defended themselves and managed to hold off the Christian attackers. However, the Christians managed to overwhelm the Jewish ghetto in the end and killed all of its Jews.[11]

At Speyer, Jewish corpses were disposed in wine casks and cast into the Rhine. By late 1349, the worst of the pogroms had ended in Rhineland. However, the massacres of Jews was starting to rise near the Hansa townships of the Baltic coast and in Eastern Europe. By 1351, there had been 350 incidents of anti-Jewish pogroms, and 60 major and 150 minor Jewish communities had been exterminated.

Causes

There are many possible reasons why Jews were accused to be the cause of the plague. Anti-Semitism was widespread in the 14th century, and in some locales, the plague was stated to be the work of Jews as retribution for the dying's wicked ways. Harbouring "enemies of Christ" was also given as a reason. Some commentators have argued that Jews who were not killed actually stood a better chance of surviving the plague because of greater cleanliness, sanitation and observance of the laws of kashrut. David Nirenberg, dean of the University of Chicago Divinity School and a specialist in medieval Jewish history, doubted whether there is credible evidence for that assertion.[15] Another reason to discount that theory is that the plague was spread by flea bites, which would have been unaffected by handwashing. Communities that valued the work of Jews in the city more saw less persecution, and those that did not value it saw more.[16]

Responses of governments

In many cities, the civil authorities either did little to protect the Jewish communities or they actually abetted the rioters.[17]

The attacks led to the eastward movement of Northern European Jewry to Poland and Lithuania, where they remained for the six centuries. King Casimir III of Poland enthusiastically gave refuge and protection to the Jews. That is consistent with his previous edicts toward Jews. On 9 October 1334, Casimir had confirmed the privileges granted to Jews in 1264 by Bolesław V the Chaste. Under penalty of death, he prohibited the kidnapping of Jewish children for the purpose of enforced Christian baptism, and he inflicted heavy punishment for the desecration of Jewish cemeteries. The king was therefore already well-disposed to Jews.[18] He was also interested in tapping the economic potential of the Jews.[19]

Church's view

Pope Clement VI (the French-born Benedictine, whose birth name was Pierre Roger) tried to protect the Jewish communities by issuing two papal bulls in 1348, on 6 July and 26 September. They stated that those who blamed the plague on the Jews had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil". He went on to emphasize, "It cannot be true that the Jews, by such a heinous crime, are the cause or occasion of the plague, because through many parts of the world the same plague, by the hidden judgment of God, has afflicted and afflicts the Jews themselves and many other races who have never lived alongside them".[2] He urged clergy to take action to protect Jews and offered them papal protection in the city of Avignon. Clement was aided by the research of his personal physician, Guy de Chauliac, who argued from his own treatment of the infected that the Jews were not to blame.[20]

Clement's efforts were in part undone by the newly-elected Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who made property of Jews killed in riots forfeit and gave local authorities a financial incentive to turn a blind eye.[21]

The influence of Clement VI and of the Church over much of Western Europe proved limited and so many of their attempts to protect Jews were futile. However, this was not the case in regions in which the Pope had considerably more influence; for example, in Avignon, the Pope saved many Jewish lives.[22]

Aftermath

As the plague waned in 1350, so did the violence against Jewish communities. In 1351, the plague and the heightened persecution was over, though the background level of persecution and discrimination remained. Ziegler (1998) comments that "there was nothing unique about the massacres."[23] 20 years after the Black Death, the Brussels massacre (1370) wiped out the Belgian Jewish community.[24] The Schaffhausen massacre in 1401,[25] expulsion orders against the Jews in Zürich, and their definitive expulsion from the city in 1634 were contributing factors in mass migrations to eastern Europe. The final instance came after Eiron (Aaron) of Lengnau was accused and executed for blasphemy.[26]

One of the most significant long-term consequences of the Black Death in Europe was the migration of Jews to Poland. Their migration to Poland was an attempt to escape from the persecution which they were being subjected to in Western Europe. This event is one of the major factors that contributed to the existence of a large population of Jews in Poland during the early 20th century. Approximately 3.5 million Jews lived in Poland at the time of Adolf Hitler's rise to power.[27]

Jewish tales

Jewish accounts of the Black Death were told in Jewish tales for nearly 350 years, but there were no written accounts of the Black Death in Jewish tales until 1696, when accounts by Yiftah Yosef ben Naftali Hirts Segal Manzpach ("Juspa Schammes" for short) began to be circulated in the Mayse Nissim. Yuzpa Shammes, was a scribe and gabbai (warden of a synagogue) of the Worms community for several decades. His accounts intend to show that the Jews were not idle because they took action in order to prevent themselves from inevitably becoming scapegoats. Despite Yuzpa's assertion that the Jews fought back during the massacres, there are contradictory accounts, which claim that there was no evidence of "armed resistance".[28]

See also

- Antisemitic trope

- History of antisemitism

- Timeline of antisemitism

- Expulsions and exoduses of Jews

- Persecution of Jews

- Pogrom

- Erfurt massacre (1349)

- Black Death in medieval culture

- Black Death in the Holy Roman Empire

- History of the Jews in Cologne § Medieval Pogroms in Cologne

- History of European Jews in the Middle Ages

- Medieval antisemitism

References

- ↑ Raspe, Lucia (2004). "The Black Death in Jewish Sources: A Second Look at Mayse Nissim". Jewish Quarterly Review. 94 (3): 471–489. doi:10.1353/jqr.2004.0001. ISSN 1553-0604. S2CID 162334762.

- 1 2 Simonsohn, Shlomo (1991). Apostolic See and the Jews. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, Vol. 1: Documents, 492. p. 1404. ISBN 9780888441096.

- 1 2 3 Diane Zahler (2009). The Black Death. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-8225-9076-7.

- ↑ Barzilay, Tzafrir. Poisoned Wells: Accusation, Persecution and Minorities in Medieval Europe, 1321-1422, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022.

- ↑ Anna Foa (2000). The Jews of Europe After the Black Death p. 146 "There were several reasons for this, including, it has been suggested, the observance of laws of hygiene tied to ritual practices and a lower incidence of alcoholism and venereal disease".

- ↑ Richard S. Levy (2005). Antisemitism p. 763 "Panic emerged again during the scourge of the Black Death in 1348, when widespread terror prompted a revival of the well poisoning charge. In areas where Jews appeared to die of the plague in fewer numbers than Christians, possibly because of better hygiene and greater isolation, lower mortality rates provided evidence of Jewish guilt".

- ↑ "The Black Death". www.jewishhistory.org. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ↑ Anna Foa (2003).The Jews of Europe after the black death . p. 13.

- ↑ Codex Judaica: chronological index of Jewish history; p. 203 Máttis Kantor (2005). "1349 The Black Death massacres swept across Europe.... The Jews were savagely attacked and massacred, by sometimes hysterical mobs—normal social order had...".

- ↑ John Marshall (2006). John Locke, Toleration and Early Enlightenment Culture; p. 376 "The period of the Black Death saw the massacre of Jews across Germany, and in Aragon, and Flanders",

- 1 2 Robert S. Gottfried (11 May 2010). Black Death. Simon and Schuster. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-4391-1846-7.

- ↑ See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, «La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire» ("The greatest epidemic in history"), in L'Histoire magazine, n° 310, June 2006, p. 47 (in French)

- ↑ Winkler, Albert (2007). The Approach of the Black Death in Switzerland and the Persecution of Jews, 1348–1349. Brigham Young University. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Durant, Will. "The Renaissance" Simon and Schuster (1953), pp. 730–731, ISBN 0-671-61600-5

- ↑ Freedman, Dan (31 March 2020). "Why Were Jews Blamed for the Black Death?". Moment Mag. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ↑ Jedwab, Remi (3 May 2020). "Pandemics and the persecution of minorities: Evidence from the Black Death". Centre for Economic Policy Research. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ↑ Howard N. Lupovitch Jews and Judaism in world history p. 92 (2009) "In May 1349, the city fathers of Brandenburg passed a law a priori condemning Jews of well poisoning: Should it become evident and proved by reliable men that the Jews have caused or will cause in the future the death of Christians...".

- ↑ "In Poland, a Jewish Revival Thrives – Minus Jews". The New York Times. 12 July 2007. Probably about 70 percent of the world's European Jews, or Ashkenazi, can trace their ancestry to Poland – thanks to a 14th-century king, Casimir III, the Great, who drew Jewish settlers from across Europe with his vow to protect them as "people of the king".

- ↑ Robert S. Gottfried (2010). Black Death. Simon and Schuster. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-4391-1846-7.

He had a Jewish mistress and seemed well-disposed in general to Jews. Perhaps too he was anxious to have the commercial skills which some of the immigrants could offer.

- ↑ Getz, Faye (1998). "Book review: Inventarium sive Chirurgia Magna. Vol. 1, Text". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 72 (3): 533–535. doi:10.1353/bhm.1998.0142. S2CID 71371675.

- ↑ Howard N. Lupovitch Jews and Judaism in world history p. 92 2009 "On July 6, 1349, Pope Clement tried to curb anti-Jewish violence by issuing a papal bull. Its effectiveness was limited by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, who made arrangements for the disposal of Jewish property in the event of a...".

- ↑ Winkler, A. (2005). The Medieval Holocaust: The Approach of the Plague and the Destruction of Jews in German, 1348-1349. Federation of East European Family History Societies, vol. XIII, 6-24.

- ↑ Philip Ziegler (1998). The Black Death "The persecution of the Jews waned with the Black Death itself; by 1351 all was over. Save for the horrific circumstances of the plague which provided the incentive and the background, there was nothing unique about the massacres."

- ↑ The Shengold Jewish Encyclopedia Mordecai Schreiber (2011). "In 1370, after the Black Death, the brutal Brussels Massacre wiped out the Belgian Jewish community"

- ↑ Denzel, Ralph (17 September 2018). "Wie 1401 ein Gerücht allen Juden in Schaffhausen das Leben kostete". Schaffhauser Nachrichten. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ↑ "Zurich, Switzerland". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ↑ Smith, Craig S. (2007-07-12). "In Poland, a Jewish Revival Thrives — Minus Jews". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

- ↑ Die Chronik des Mathias von Neuenburg, 1955. "While a Christian chronicler reports that during the pogrom of March 1, 1349, the beleaguered Jews of Worms set fire to their own houses, as may have happened elsewhere, there is no evidence of armed resistance".

Further reading

- Winkler, Albert (2007). "The Approach of the Black Death in Switzerland and the Persecution of Jews, 1348–1349," Swiss American Historical Society Review, vol. 43 (2007), no. 3, pp. 4–23.

- Winkler, Albert (2005). "The Medieval Holocaust: The Approach of the Plague and the Destruction of Jews in Germany, 1348–1349," Federation of East European Family History Societies, vol. 13 (2005), pp. 6–24.