Black Ladies today: a large private residence incorporating 16th and 17th century structures erected by the Giffard family after the dissolution of the priory. | |

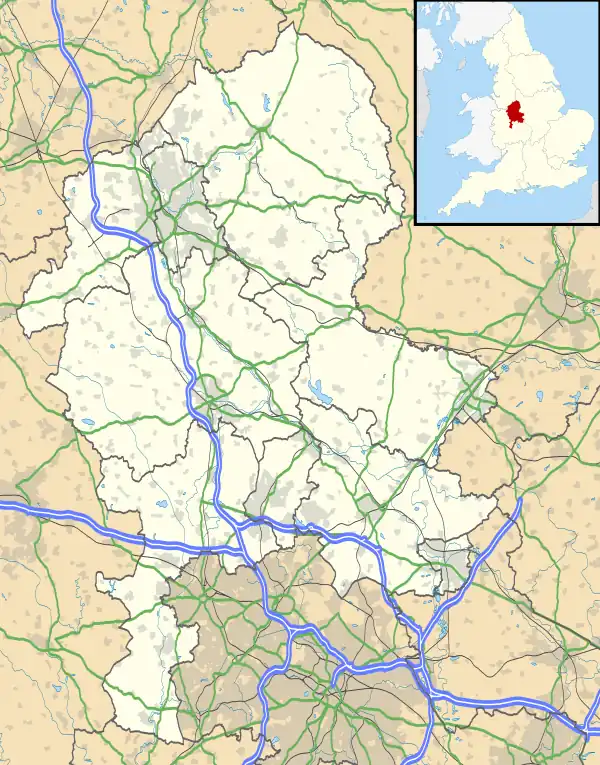

Location within Staffordshire | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Convent of St. Mary of the Black Ladies |

| Other names | Community of the Black Nuns at Brewood |

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | Mid-12th century |

| Disestablished | 1538 |

| Dedicated to | Mary, mother of Jesus |

| Diocese | Diocese of Coventry and Lichfield |

| Controlled churches | Broome, Worcestershire Possibly Rode, Somerset |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Possibly Roger de Clinton |

| Important associated figures |

|

| Site | |

| Location | Near Brewood |

| Coordinates | 52°40′53″N 2°13′38″W / 52.6815°N 2.2271°W |

| Public access | no |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Black Ladies |

| Designated | 16 May 1953 |

| Reference no. | 1039336 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Garden walls to east, north and south of Black Ladies, with gate piers |

| Designated | 16 May 1953 |

| Reference no. | 1039337 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Tudor Barn, Blackladies |

| Designated | 28 March 1985 |

| Reference no. | 1374042 |

Black Ladies Priory was a house of Benedictine nuns, located about 4 km west of Brewood in Staffordshire, on the northern edge of the hamlet of Kiddemore Green. Founded in the mid-12th century, it was a small, often struggling, house. It was dissolved in 1538, and a large house was built on the site in Tudor and Jacobean styles by the Giffard family of Chillington Hall. Much of this is incorporated in the present Black Ladies, a large, Grade II*-listed, private residence.

Name and dedication

The priory was dedicated to St. Mary but was often simply referred to as "Black Ladies;"[1] the elided form, "Blackladies," is also used. The Benedictine nuns resident in the priory wore black habits, but this was so elsewhere too. The use of the term Black Ladies for the Brewood priory is in contradistinction to another priory in the neighbourhood – an Augustinian convent dedicated to St. Leonard and known as White Ladies Priory.[2] The two priories were founded at about the same time and were of about the same size and importance. Medieval documents, particularly in the reign of Henry III frequently refer to the nuns or the priory of Brewood without indicating which community is meant. It would have made sense to distinguish the communities by the colour of their habits.

The precise formula used to refer to the convent officially evidently varied through time. The 14th century seal of the priory bore the words: sigillum conventus sancte Marie nigrarum dominarum – seal of the convent of St. Mary of the Black Ladies.[3] A partial seal surviving from 1538 shows a seated Madonna and Child in a canopied niche with the inscription: [s]igillum commune nigrarum monialium de bre[. . .][4][5] – which translates as [s]eal of the community of the Black Nuns at Bre[...].

Foundation

Black Ladies was situated within the manor of Brewood, which was held by the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, and probably on land granted by a bishop[6] This has led to the suggestion that it was founded by one of the bishops, and the one candidate seems to be Roger de Clinton, a powerful magnate who was a mainstay of King Stephen's regime during the Anarchy of the mid-12th century and who died in 1148. Clinton not only had the power and resources but is known to have founded Farewell Priory[7] – not far away in Cannock Chase and also small house dedicated to St. Mary. Although there is no positive evidence for the founder, its existence is attested mid-century in a deed by which Ralph Bassett, a local landowner, grants the nuns small areas of land at Pattingham and Hardwick.[8]

The secure existence of Black Ladies was confirmed in the next century. Pope Gregory IX (1227–1241) took the priory under his protection and confirmed it in its property holdings, both present and future.[9] He explicitly recognised the right of the sisters to elect their own prioress, although the bishop was to ordain their chaplain.

Estates, endowments and finances

The priory was never wealthy and most of its income came from small, scattered estates, close by in Staffordshire or in neighbouring counties. A deed of 1170 has the nuns of Brewood and Blithbury, at Mavesyn Ridware, giving land they held at Ridware to the lord of the manor, in return for an annual rent of two shillings and confirmation of meadowland they already had there.[10] This shows the nuns busily trying to make the most of a small holding. It also shows that there was already some sort of special relationship between Black Ladies and Blithbury. The Blithbury nuns obtained land at Gailey in Penkridge parish around 1160, but this had passed to Black Ladies by 1189,[11] when Henry II took it under royal control, leaving his son King John to compensate Black Ladies with the manor of Broome in 1200.[12] Three years later, the prioress vindicated her claim to the advowson of the church at Broome. Alexander de Bransford, the parson of Broome who died around 1205, had been presented by the previous manorial lord, Richard of Ombersley, whose father Maurice was reckoned the founder of the church.[13] Broom had been created by partitioning Clent and granted to Maurice in 1154.[14] The church was thus sometimes considered a chapelry of the church at Clent and Herbert, the vicar of Clent, claimed the right to present a successor. The prioress successfully maintained that the king had acquired the advowson when he confiscated the manor and had handed over this potentially valuable asset to Black Ladies, although it was not mentioned in the charter of 1200. The priory seems to have retained the advowson thereafter.[15]

The priory had its demesne – its own site and small areas in the manor of Brewood. These latter were exchanged in the 13th century for a small, enclosed area close to the priory. Similarly, the nuns exchanged the Pattingham lands for an assart at Chillington, paying Ralph Bassett's widow, Isabel de Pattingham, £1 for the transaction.[16] At some time in the late 12th century they acquired lands at Rudge, Shropshire.[17] In 1204, William de Rudge charged them 4 marks and an annual rent of three pence to consolidate and extend their holding, exchanging land he had given them earlier. He also handed over lands previously held by one of his tenants for a payment of a palfrey and four marks, and an annual rent of 12 pence. In every case, the nuns seem to be consolidating scattered and unremunerative holdings to try to obtain a better and more secure income. A profitable asset was a mill at Chetton, given by the lady of the manor, Sybil de Broc, in 1225. In 1272 the nuns received lands at Broomhill, just east of the priory, from the heirs of Ralph de Coven,[18] as well as a rent in Brewood and another worth 16d. at Horsebrook.[19] These were conveyed to the priory through a fine of lands levied by the prioress Amabilia or Mabel.

Kings made several small gifts and a few important concessions. In 1204 King John gave alms amounting to two marks each to a number of small communities in the Midlands, including both Brewood and Blithbury.[20] Henry III made a number of grants "to the nuns of Brewood," without specifying whether the Benedictines of Black Ladies or their Augustinian neighbours were meant. These included permission to assart three acres of woodland in Sherwood Forest in 1241;[21] three oaks from Kinver Forest in 1256;[22] and a further 10 oaks from the same forest in 1267.[23] However, a grant of 8 September 1241 was specifically to the "black nuns of Brewood:" one mark so that the sisters could redeem their chalice, which was in pledge[24] – an indicator of the poverty of the community. Probably more important was Henry's confirmation in 1267 of his father's charter of 1200 which had granted the land at Broom in exchange for Gayley.[25]

In 1275 Mabel and Alice, the prioresses respectively of Black Ladies and Blithbury, recorded a land deal with one Robert de Pipe.[26] Thereafter, definite references to the priory at Blithbury cease. Long associated with Black Ladies, it seems to have been absorbed into it in the late 13th century. Most of its lands appear in later records as assets of Blackladies. By the 16th century the Blithbury lands made a large contribution to the revenues of Black Ladies.[27][28]

In 1291[29] Pope Nicholas IV granted an indulgence to all who would travel to Black Ladies to celebrate four Marian festivals and the church's anniversary there.[30] This amounted to one year and forty days of penance – a considerable incentive to make the pilgrimage and so potentially a source of considerable income from offerings. In the Taxatio Ecclesiastica of that year the only property of Brewood recorded was the mill at Chetton, which was worth 16 shillings.[4] However, in the first decades of the 14th century the nuns were still poor enough to pursue a convoluted dispute with the vicar of Brewood over who should receive tithes on the wool of animals not owned by them but grazed on their land.[31] However, not much later their assessments for subsidies to the king were assessed at 2 shillings in 1327[32] and 3 shillings in 1333[33] – the latter one of the highest in the area.

On 16 October 1346, while campaigning in France at an important stage of the Hundred Years' War, Edward III licensed the prioress and convent of Brewood to appropriate the church of Rode in Somerset, where they already held the advowson.[34] There is no indication of which prioress and convent. However, this was at the request of Thomas Swynnerton and Alice Swynnerton is known to have been prioress of Black Ladies until 1332.[35] There is no sign that the appropriation was ever implemented. More certain is a receipt of 28 September 1394 by which Petronilla, named as prioress of the Black Nunnery of Brewood, acknowledged a gift of £100 from Thomas Gech to establish a chantry for Thomas de Brompton, formerly lord of Church Eaton, and his forebears. It is possible that Gech had married Brompton's widow, Isabella, but this is disputed.[36][37] This was the largest recorded gift to the priory.[38]

A canonical visitation was made by Bishop Norbury around 1323: the precise date is unknown and there is a lacuna in the bishop's register for this year.[39] It found the financial situation and management unsatisfactory.[40] He forbade disbursements of pensions, liveries and corrodies – that is incomes paid in cash, clothing or food and lodging – unless his express permission was first sought. However, a visitation of 1521 found that the priory had no debts and its income stood at £20 13s. 4d.[41] In 1535, a year before the Dissolution of the Monasteries began, the Valor Ecclesiasticus reported the priory drawing most of its income from its own house and demesne, with further income from lands and rents only in Horsebrook (in Brewood parish), Broom and Kidderminster.[42] A number of landowners were recorded as contributing small alms for the upkeep of the nuns – the largest donor being Sir John Giffard of Chillington Hall, who gave 2s. 6d. Others were Sir Roger Corbet, said to be of Dawley, who gave two shillings; William Woodhouse of Albrighton, who gave a shilling; a member of the Vernon family of Tong, presumably George Vernon (MP for Derby and Derbyshire), who could easily afford his two shilling donation; and one of the Blakemore family of Bradley, Staffordshire, who donated a shilling. Income from land and alms together added up to £11 1s. 6d.,[43] which must be incomplete. Other reports simply do not harmonise with this picture.[44] Documents from only a few years later add income from Blithbury, Shredicote in Bradley, Stretton, Hampton Lovett and Hunnington in Halesowen.[27][28] Apart from the demesne at Brewood, the most valuable incomes came from Broome and Blithbury, each bringing in around £3. The total net income in 1537 was £17 2s. 11d. As the visitation of 1521 had found no debts, the priory must have become more financially stable in its last decades, although this was probably the result of improved financial management as much as increased revenue. The amounts involved are still paltry – far below the threshold of £200 net set for dissolution of the lesser monasteries under the Suppression of Religious Houses Act 1535 and it was listed as such in an official schedule.[45] So the dissolution of the priory was a foregone conclusion, purely on financial grounds.

The monastic life

The community of Benedictine nuns at Black Ladies was very small. At dissolution in 1538, there were only three nuns and the prioress to receive pensions.[46] A canonical visitation in 1521 had also found only four nuns living in the priory.[41] It seems that the community never numbered more than a handful. They were, however, supported by a number of lay servants and officials. A chaplain and seven other employees had to be paid off at the dissolution.[46] As well as the financial problems associated with small and scattered endowments, the community seems to have struggled with management and governance.

The conviction of the nuns for poaching in 1286 illustrates both problems. The incident concerned seems to have happened about a decade earlier, so justice, while certain, was not swift. After a stag had escaped from the royal huntsman in Gailey Hay, part of the royal forest of Cank or Cannock Chase, it had fled the forest and drowned in the priory fishpond. John Giffard of Chillington Hall, a short distance to the south, had dragged the carcass from the pond and claimed the whole of it, although one John Whitmore had played a part in its demise by shooting at it. Giffard then took half of the animal home with him, leaving the remainder for the nuns. Under Henry III's Charter of the Forest, this was no longer a capital offence, although it remained very serious. When the matter came to trial, both Giffard and Whitmore were imprisoned and fined, Giffard 20 shillings and Whitmore a mark. Of the nuns, however, the judgement ran: "as they are poor, they are pardoned for the good of the king’s soul."[47]

The zealous Bishop Northburgh found numerous shortcomings – minor and more serious, moral and financial – when he carried out a canonical visitation around 1323. Northburgh was clearly a stickler for transparent management and that of the priory fell far short of the best 14th century practice. He demanded that the prioress and other office holders be prepared to present the accounts. The two most senior lay staff were sacked: Annabel de de Hervill, the cellaress or purveyor of food and drink, and Robert de Herst, the keeper of the temporalities or estate manager.[40] Northburgh froze admissions to the priory and forbade the prioress taking bribes from prospective members of the community – which presumably had happened to this point. Northburgh was also forced to reiterate many details of the basic monastic disciplines of poverty, chastity and obedience. One of the nuns was receiving a rental income for personal use and was ordered to share it with the whole house. The prioress was instructed to take her meals in the refectory and to sleep in the dormitory, like the others. Lay people were not to sleep in the convent, and this included the prioress's maid. The nuns were not to converse with outsiders, and nuns were not to leave the cloister without good reason: one Emma of Bromsgrove was named as falling short in this regard. A Franciscan friar was appointed as a confessor to the nuns. It is unclear whether an excess of financial zeal led to a brush with the law in 1324. At Easter of that year Prioress Alice Swynnerton was accused, with two others, of taking by force two oxen, valued at 40 shillings, the property of Clement of Wolverhampton, at Horsebrook. She was distrained and her co-accused arrested by the sheriff to secure their appearance at the next court sessions.[48] At Trinity the charge was expanded to include a total of 100 shillings' worth of goods and chattels. However, Alice and her accomplices did not respond to the summons and the 10 shillings already distrained from her was forfeit.[49]

Evidently there were problems in maintaining even a semblance of leadership. Bishops were forced to intervene three times in the 15th century – in 1442, 1452 and 1485 – to appoint a prioress because of prolonged vacancies, although the nuns were supposed to elect their own head.[50] However, the visitation of 1521 found the priory in good order, although one nun commented that young girls slept in the dormitory with the nuns.[41]

Prioresses

The following list is based on that in the Victoria County History,[51] with additions from other referenced sources.

Isabel granted land at Brewood to Roger de Meyland, bishop of Coventy and Lichfield.[52] This dates her period of office as being at least partly contemporary with his episcopate, approximately 1258–95, although it is impossible to know whether she preceded or succeeded Mabel.

Mabel or Amabilia, occurs 1272 obtaining land at Horesebrook[19] and again witnessing a land transfer in 1275.[26] (fn. 37)

Emma occurs 1301.

Alice de Swynnerton was sued for return of stolen cattle in 1324[48] and resigned in 1332.

Helewis of Leicester, formerly a nun at the priory,[53] was elected in 1332 and still living in 1373.

Parrnel or Petronilla gave a receipt for a gift of £100 in September 1394[36] and was still living in 1412.

Margaret Chilterne, formerly a nun at Chester Priory, was appointed in 1442[54] and resigned by 1452.

Elizabeth Botery, a nun of Brewood, was appointed by the bishop in 1452 after a long vacancy[55] and died in 1485.

Margaret Cawardyn, appointed 1485, was formerly sub-prioress of Brewood.[56]

Isabel Lawnder was probably from Beech, near Stone, Staffordshire, the daughter of Ralph Launder.[57] She was prioress by 1521 and held the post until the dissolution of the priory in 1538. Later she seems to have lived with her sister Agnes Beech and nephew John. One of the other nuns at Black Ladies at the dissolution was Alys Beech, possibly a relative.[58]

Dissolution and sale

Black Ladies, Brewood, was scheduled for dissolution with the rest of the lesser monasteries. The prioress at the time of dissolution was Isabel Lawnder, who had been in office at the visitation of 1521.[59] However, bidding for the site went on for at least a year before the actual dissolution. There was considerable interest in the site from local landowners – especially from Edward Littleton[60] of Pillaton Hall, near Penkridge, who built his family's fortune through a career of exploiting leases and purchases of ecclesiastical lands.[61] A letter was sent on 11 October 1538 to Thomas Legh, who was dealing with the surrender of Black Ladies for the Court of Augmentations, stating that the lease of the house and farm was granted to Thomas Giffard of Stretton (in Penkridge), a gentleman usher of the chamber and the son of Sir John Giffard of Chillington.[62]

Legh, who had earned a reputation for his high-handed treatment of monks and nuns, took over from Prioress Isabel on 16 October 1538.[63] She received a lump sum of 40 shillings[46] for her cooperation and an annual pension of £3 6s. 8d. thereafter.[58] The other three sisters each received precisely half these amounts: their names are given as Christabell Smyth, Alys Beech and Felix Baggeshaw. These pensions were confirmed by the Court of Augmentations on 1 February 1539.[64] £3 18s. 2d. was used to pay off the eight servants of the priory, including £1 10s. for William Parker, the chaplain. The goods and chattels were then auctioned off and recorded as bought by Giffard, with a total value of £7 6s. 1d – a very small sum even by the standards of the time. They included three bells in the church tower, a silver chalice, three spoons, one horse, a wain and a dung cart, together with the furnishings and fittings of the brewery, cheese loft and other buildings.[27][65] However Legh then wrote to Thomas Cromwell, enclosing the letter about Giffard's lease of the property and pointing out that Littleton too had been given a firm promise that it would be his. He sarcastically noted that the new custodian of Lilleshall Abbey, to which he had travelled immediately from Black Ladies, was concerned lest he too be supplanted in his absence.[66] He had, he said, put Littleton and Giffard jointly in charge "till they know the king’s further pleasure."

Ultimately Giffard emerged as the victor and in February 1539 he was sold the site, watermill, demesne lands, church and churchyard, steeple of Black Ladies, worth £7 9s. 1d. a year, for the sum of £134 1s. 8d.[67] The sale was confirmed by the Court of Augmentations.[68]

Later history

With Thomas Giffard's brief succession to his father's lands, from 1556 to 1560, Black Ladies became part of the Giffard patrimony. While ultimately it was to descend with Chillington itself, Thomas initially used Black Ladies to make provision for a younger son, Humphrey: after Humphrey's death it was to revert to Thomas's eldest son and heir, John Giffard. In fact, Humphrey outlived John, so the house passed to John's heir, Walter, some time after 1614. According to the Victoria County History account of Black Ladies Priory, "no part of the priory buildings has survived."[70] This echoes the earlier VCH account of the estate, which stated baldly that: "No part of the monastic buildings has survived."[71] However, the Brewood parish council website asserts: "Much of the structure pre-dates the Dissolution".[72] This is not supported by the building's English Heritage listing, which describes it as: "Country house. Late C16 or early C17 with C20 renovations."[73] The present house visibly incorporates considerable portions of the Tudor and Jacobean structures erected by the Giffards over the century and so after the Dissolution. There was also a complex of service and agricultural buildings. The stables, known as the Tudor Barn, now form a separate house, fronted by the priory pond. During the Commonwealth and the Protectorate Blackladies was temporarily lost to the Giffards, as they suffered sequestration because of their royalist activities.[74] From the early 18th century all or parts of it were leased out[75] and in 1893 it was finally sold, to Major Ernest Vaughan.[76]

The continuing religious importance of Black Ladies beyond the English Reformation derives from Thomas Giffard's commitment to Catholicism when England returned decisively to a Protestant path, early in the reign of Elizabeth I. His successors and most member of the Giffard family were to remain Catholic for more than three centuries. The Giffards became leaders of Catholic Recusancy in the region and stayed true to their faith throughout the vicissitudes of the Reformation, the English Civil War and the Penal Laws. The Giffards protected the large Catholic community in the Brewood area, many of whom were their tenants, and their chapel at Chillington was used for worship by the local Catholic community. Until about 1846 Black Ladies too included a family chapel, a requisite for Catholic gentry families.[77] When the Chillington chapel was closed, due to building work, in the 18th century, worship was transferred to the chapel at Black Ladies, and it continued there until 1844.[78] It lay to the north of the house, connected by a passageway, and a witness in 1846 considered it to pre-date the main structure, apparently built from masonry of the convent.[79] In June 1844 year the chapel had been definitively replaced by the dedication of a purpose-built Catholic church at Brewood, dedicated, like the priory, to St. Mary.[80] The church contains a Madonna and child, described by the church website as "ancient". It is thought to have sustained leg damage from a sword stroke during a search of Black Ladies' by Parliamentary soldiers during the escape of Charles II.[81] The "wound" was said to weep continually and the liquid was used to effect cures. The statue appears to be in a baroque style typical of the early to mid-17th century, making it likely it was part of the Giffards' chapel at Black Ladies, rather than of the priory: there is no record of such an image at the latter.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 1. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), footnote 1. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 46. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- 1 2 Dugdale, p. 499.

- ↑ W. de Gray Birch, p. 457.

- ↑ Midgley (ed). Brewood: Introduction, manors and agriculture: Lesser Estates, note anchor 610. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 5.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 2. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 3. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 12. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 4. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Midgley (ed). Penkridge: Introduction and manors, note anchor 332. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 5.

- ↑ Rotuli Chartarum in Turri Londinensi Asservati, p. 80.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 3, p. 127.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 2, p. 117.

- ↑ Page and Willis-Bund (eds). Parishes: Broom, note anchor 30.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 10. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 9. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 17. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- 1 2 Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 1, p. 332.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 2, p. 119. For explanation, see p. 123.

- ↑ Close Rolls of Henry III, 1237–1242, p. 273.

- ↑ Close Rolls of Henry III, 1254–1256, p. 344.

- ↑ Close Rolls of Henry III, 1264–1268, p. 331.

- ↑ Calendar of Liberate Rolls, 1240–1245, p. 71.

- ↑ Calendar of Charter Rolls, 1257–1300, p. 79.

- 1 2 Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Blithbury (Black Ladies), note anchor 8. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- 1 2 3 Dugdale, p. 501.

- 1 2 Hibbert, p. 94.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 6, p. 152, F.274.

- ↑ Regesta 46, 1291–1292, 8 Ides May. in Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland: Volume 1, 1198–1304.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 21. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 7, p. 236.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 10, p. 121.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1345–1348, p. 475.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), footnote 23. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- 1 2 Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 4, part 2, p. 15, footnote.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 20, p. 153 and footnote 4.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 23. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 1, p. 250.

- 1 2 Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 24. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- 1 2 3 Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 27. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 92.

- ↑ Dugdale, p. 500.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 93.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, volume 10, p. 515, no. 1238.

- 1 2 3 Hibbert, p. 227.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 5, part 1, p. 163.

- 1 2 Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 9, part 1, p. 101.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 9, part 1, p. 104.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchors 25 and 26 in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies): Prioresses in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Collections for a History of Staffordshire, volume 6, p. 146, F.246b.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), footnote 40. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), footnote 42. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), footnote 43. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), footnote 44. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), footnote 45. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- 1 2 Hibbert, p. 228.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 45. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 33. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Colleges: Penkridge, St Michael, note anchor 67. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, volume 13, part 2, no. 586.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, volume 13, part 2, no, 627.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, volume 14, part 1, Augmentation Book 211, no. 103b.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 22-6.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, volume 13, part 2, no, 629.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, volume 14, part 1, no. 403/30.

- ↑ Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, volume 14, part 1, Augmentation Book 211, no. 54d.

- ↑ Palmer and Crowquill, p. 48.

- ↑ Baugh et al. Houses of Benedictine nuns: The priory of Brewood (Black Ladies), note anchor 35. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 3.

- ↑ Midgley (ed). Brewood: Introduction, manors and agriculture: Lesser Estates, following note anchor 627. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 5.

- ↑ Brewood Village Web Site

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1039336)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ↑ Midgley (ed). Brewood: Introduction, manors and agriculture: Lesser Estates, note anchor 616. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 5.

- ↑ Midgley (ed). Brewood: Introduction, manors and agriculture: Lesser Estates, note anchor 633. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 5.

- ↑ Midgley (ed). Brewood: Introduction, manors and agriculture: Lesser Estates, note anchor 623. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 5.

- ↑ Midgley (ed). Brewood: Introduction, manors and agriculture: Lesser Estates, following note anchor 628. in A History of the County of Stafford, volume 5.

- ↑ Hicks Smith, p. 44.

- ↑ Palmer and Crowquill, p. 49.

- ↑ Hicks Smith, p. 90.

- ↑ History page, St Mary's church website Archived March 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

References

- G C Baugh; W L Cowie; J C Dickinson; Duggan A P; A K B Evans; R H Evans; Una C Hannam; P Heath; D A Johnston; Hilda Johnstone; Ann J Kettle; J L Kirby; R Mansfield & A Saltman (1970). Greenslade, M. W. & Pugh, R. B. (eds.). A History of the County of Stafford. Vol. 3. London: British History Online, originally Victoria County History. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Bliss, William Henry, ed. (1893). Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland, 1198–1304. Vol. 1. London: British History Online, originally HMSO. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Dugdale, William; Dodsworth, Roger. John, Caley; Henry, Ellis; Bandinel, Bulkeley (eds.). Nunnery of "the Black Ladies of Brewood". Vol. 4 (1846 ed.). London: James Bohn. pp. 499–502. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) At Hathi Trust. - Gairdner, James, ed. (1887). Letters and Papers, Domestic and Foreign, of the Reign of Henry VIII. Vol. 10. London: HMSO. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Gairdner, James, ed. (1893). Letters and Papers, Domestic and Foreign, of the Reign of Henry VIII. Vol. 13. London: British History Online, originally HMSO. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Gairdner, James, ed. (1894). Letters and Papers, Domestic and Foreign, of the Reign of Henry VIII. Vol. 14. London: British History Online, originally HMSO. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- de Gray Birch, Walter (1887). Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts of the British Museum. Vol. 1. London: Longman. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Hardy, Thomas Duffus, ed. (1837). Rotuli Chartarum in Turri Londinensi Asservati. Vol. 1. London: uk Public Record Office. Retrieved 9 November 2016. At Bayerische StaatsBibliothek digital.

- Hibbert, Francis Aidan, ed. (1910). The Dissolution of the Monasteries as Illustrated by the Suppression of the Religious Houses of Staffordshire. London: Pitman. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Hicks Smith, James (1864). Brewood: a Résumé Historical and Topographical (1874 ed.). Wolverhampton: William Parke. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1906). Calendar of the Charter Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office, 1257–1300. London: HMSO. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1930). Calendar of the Liberate Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office, 1240–1245. London: HMSO. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1903). Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office, Edward III 1345–1348. Vol. 7. London: HMSO. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1911). Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III Preserved in the Public Record Office, 1237–1242. London: HMSO. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1931). Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III Preserved in the Public Record Office, 1254–1256. London: HMSO. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1937). Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III Preserved in the Public Record Office, 1264–1268. London: HMSO. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Midgley, L. Margaret, ed. (1959). A History of the County of Stafford. Vol. 5. London: British History Online, originally Victoria County History. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Page, William Henry; Willis-Bund, John William, eds. (1924). Parishes: Broom. Vol. 4. London: British History Online, originally Victoria County History. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Palmer, Francis Paul; Crowquill, Alfred (1846). The Wanderings of a Pen and Pencil. London: Jeremiah How. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1880). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 1. London: Harrison. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1881). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 2. London: Harrison. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1882). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 3. London: Harrison. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1883). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 4. London: Harrison. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1884). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 5. London: Harrison. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1886). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 6. London: Harrison. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1886). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 7. London: Harrison. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1888). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 9. London: Harrison. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1889). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 10. London: Harrison. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1899). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 20. London: Harrison. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

External links

- Staffordshire Past Track has a selection of copyright photographs and allows comparison of the site on maps of various dates.

- Historic England. "Black Ladies (1039336)". National Heritage List for England.

- Historic England. "Tudor Barn Black Ladies (1374042)". National Heritage List for England.

- Historic England. "The garden walls at Black Ladies (1039337)". National Heritage List for England.

- British Listed Buildings Alternative source for listing details and quick links to maps, etc.

- Geograph.org.uk images of the area.