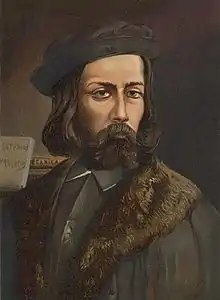

Blasco de Garay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1500 |

| Died | 1552 (aged 51–52) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Navy of Spain |

| Rank | Captain |

| Other work | Inventor |

Blasco de Garay (1500–1552) was a Spanish navy captain and inventor.

De Garay was a captain in the Spanish navy in the reign of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. He made several important inventions, including diving apparatus, and introduced the paddle wheel as a substitute for oars. In the nineteenth century, a Spanish archivist claimed to have discovered documents that showed that de Garay had tested a steam-powered ship in 1543.[1] However, these claims have been discredited by the Spanish authorities.[2]

Biography

There is no record of Blasco de Garay's birth or of his familial connections except for the mention in his memorial of an older brother, a Diego de Alarcon, who lost his life as an army captain in Italy. At the time there were several people of the Garay name who distinguished themselves in letters and in the military service who seem to have been from the minor nobility in the Castilian city of Toledo. That his brother's name was in the Castilian form "Diego" (James) supports a Castilian origin. The most plausible account is that he was an impoverished minor nobleman, educated in letters, who out of necessity went into the King's service but, as he wrote, dedicated himself to the sciences and invention.

Inventions

Garay himself sent the emperor a document setting out eight inventions which included:[3]

- A way to recover vessels underwater, even if they were submerged a hundred fathoms deep, with only the aid of two men.

- An apparatus by which anyone could be submerged under water indefinitely

- Another device to detect objects on the seabed with the naked eye.

- A way to keep a light burning underwater.

- A way to sweeten brackish water.

Steamship controversy

The attribution to Blasco de Garay of the testing of a steam engine made on a boat in the port of Barcelona was claimed in 1825 by Tomás González, director of the royal archives of Simancas, to the distinguished historian Martín Fernández Navarrete. González stated that in a file he had found, there is documentation endorsing a test conducted June 17, 1543[4] by the Naval Captain and Engineer of the navy of Charles V of a navigation system with no sails or oars containing a large copper of boiling water. Navarrete published González's account in 1826 in Baron de Zach's Astronomical Correspondence.[5] The letter from González to Martín Fernández Navarrete is as follows:

- "Blasco de Garay, a captain in the navy, proposed in 1543, to the Emperor and King, Charles the Fifth, a machine to propel large boats and ships, even in calm weather, without oars or sails. In spite of the impediments and the opposition which this project met with, the Emperor ordered a trial to be made of it in the port of Barcelona, which in fact took place on the 17th on the month of June, of the said year 1543. Garay would not explain the particulars of his discovery: it was evident however during the experiment that it consisted in a large copper of boiling water, and in moving wheels attached to either side of the ship. The experiment was tried on a ship of two hundred tons, called the Trinidad, which came from Colibre to discharge a cargo of corn at Barcelona, of which Peter de Scarza was captain. By order of Charles V, Don Henry de Toledo the governor, Don Pedro de Cordova the treasurer Ravago, and the vice chancellor, and intendant of Catalonia witnessed the experiment. In the reports made to the emperor and to the prince, this ingenious invention was generally approved, particularly on account of the promptness and facility with which the ship was made to go about.

- The treasurer Ravago, an enemy to the project, said that the vessel could be propelled two leagues in three hours that the machine was complicated and expensive and that there would be an exposure to danger in case the boiler should burst. The other commissioners affirmed that the vessel tacked with the same rapidity as a galley maneuvered in the ordinary way, and went at least a league an hour.

- "As soon as the experiment was made Garay took the whole machine with which he had furnished the vessel, leaving only the wooden part in the arsenal at Barcelona, and keeping all the rest for himself.

- "In spite of Ravago's opposition, the invention was approved, and if the expedition in which Charles the Vth was then engaged had not prevented, he would no doubt have encouraged it. Nevertheless, the emperor promoted the inventor one grade, made him a present of two hundred thousand maravedis, and ordered the expense to be paid out of the treasury, and granted him besides many other favors."[1][4][6]

- "This account is derived from the documents and original registers kept in the Royal Archives of Simancas, among the commercial papers of Catalonia, and from those of the military and naval departments for the said year, 1543." Simancas, August 27, 1825, Tomás González.[1][7]

Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont, a Spanish soldier, painter, cosmographer, musician, and above all, inventor, registered in 1606 the first patent for a steam machine, so he is credited as the inventor of all kinds of steam machines.

Steamboats were in fact not introduced to Spain until 1817.[8] Real Fernando, launched in 1817 and which plied the Guadalquivir River from Sevilla to Sanlucar, was probably the first steamboat built in Spain. She was joined by PS Hope, built at Bristol in 1813.[9]

The belated claims made on behalf of Blasco de Garay have since been discredited by the Spanish authorities.[2]

The failure to find documentation confirming that letter led to a controversy between French and Spanish scholars.[10] The issue gained such popularity that Honoré de Balzac wrote a comedy, made of five acts,[11] with the theme as an argument entitled Les Ressources de Quinola[12] which premiered in Paris on March 19, 1842 and which tended to be sympathetic to the Spanish claim.[13][14]

References

- 1 2 3 Blasco de Garay's 1543 Steamship, Rochester History Resources, University of Rochester, 1996, archived from the original on April 26, 2008, retrieved April 24, 2008

- ↑ Arnold, J. Barto; Weddle, Robert S. (1978), The Nautical Archeology of Padre Island: The Spanish Shipwrecks of 1554, Academic Press, p. 81, ISBN 0-12-063650-6

- 1 2 Lardner, Dionysius (1840), The Steam Engine Explained and Illustrated: With an Account of Its Invention, Taylor and Walton, p. 16

- ↑ Lardner, Dionysius (1851), The steam engine familiarly explained and illustrated; with numerous illustrations, Upper Gower Street, and Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row, London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly, p. 13

- ↑ Timbs, John (1860), Stories of Inventors and Discoverers in Science and the Useful Arts: A Book for Old and Young, Franklin Square, New York: Harper & Brothers, p. 275

- ↑ Jones, M.D., Thomas P., ed. (1840), Journal of the Franklin Institute of the State of Pennsylvania and Mechanics' Register. Devoted to Mechanical and Physical Science, Civil Engineering, the Arts and Manufactures, and the Recording of American and Other Patented Inventions, vol. XXV, Philadelphia: The Franklin Institute, p. 6

- ↑ M.M.del Marmol. "Idea de los Barcos de vapor", Sanlucar, 1817.

- ↑ G.E.Farr,"West Country Passenger Steamers", London, 1956, page 14.

- ↑ Lindsay, William Schaw (1876), History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce, S. Low, Marston, Low, and Searle, p. 12

- ↑ Wedmore, Frederick; Anderson, John Parker (1890), Life of Honoré de Balzac, W. Scott, p. ii

- ↑ The Resources of Quinola by Honoré de Balzac, Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Peltier, L. (March 21, 2008), 1543 – 1555. Copernic. Potosi. Nostradamus. Ambroise Paré, Un journal du monde

- ↑ Urban, Sylvanus, ed. (July–December 1884), The Gentleman's Magazine, vol. CCLVII, London: Chatto & Windus, Piccadilly, p. 308

Further reading

- H. P. Spratt,The Birth of the Steamboat, London, 1958

- H. P. Spratt, The Prenatal History of the Steamboat, Newcomen Transactions, Vol.30, 1955–7, page 13.