Blois-Vienne | |

|---|---|

._(10652807333).jpg.webp) Blois-Vienne Church, dedicated to St Saturnin of Toulouse | |

| Coordinates: 47°20′44″N 1°12′06″E / 47.3455°N 1.2016°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | |

| Department | |

| Arrondissement | Blois |

| Canton | Blois-3 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.5 sq mi (6 km2) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 10,000 |

| • Density | 4,000/sq mi (1,500/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Viennese French: Viennois(e) |

| INSEE | 41018 |

| Postal code | 41000 |

Blois-Vienne (French pronunciation: [blwavjɛn]), or merely Vienne for locals, is the common name given to the southern part of Blois, central France, separated from the rest of the city by the natural border of the Loire river. It corresponds to the subdistricts of St Saturnin, La Creusille, Les Métairies (college and cemetery) and La Vaquerie, but also include the hamlets of Bas-Rivière and Béjun, although these ones are now administratively attached to the neighboring commune of Chailles. In other words, it is now the left bank of the Loire in Blois.

Nowadays this borough (or district) of around 10,000 inhabitants is the physical heritage of the former village of Vienne-lez-Blois, which remained independent of the royal domain until the beginning of the 17th century, when it was attached to the city, first as a suburb, then as a district.

History

Ancient times

No written documentation about the area during the ancient times was found. However, in 2013, French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP in French) conducted excavations in Vienne and found out evidence of Gaulish presence as early as the 4th century BCE (more precisely, they were from Carnutes tribe).[1] Also, all the surroundings were different compared to what they are nowadays: at that era, Vienne have been built on sort of a river island that was likely to be surrounded by water in the event of heavy rains or floods.[2] However, historians do not agree about the nature of the site. On the one hand, it would have been built on a presque-isle, surrounded by marshy spaces, becoming a real island only when the river floods.[3] On the other hand, other historians believe that Vienne was rather a proper river island, even during the Middle Ages.[4]

The Gaulish settlement was named Vienna (where Vienna would mean "river" in an ancient local dialect), and the island was known as Insula Evenna (literally "Vienna island").[5]

When the Romans conquered Gaul during the 1st century BCE, they built a first wooden bridge (so-called Ancient bridge), the foundations of which can be seen nowadays when the Loire river experiments drought flow.[6] Before that, the locals likely used the submersible dike still visible in Blois at the level of St-Nicolas church, on the right bank, to cross the river.[7][8]

Nonetheless when Romans started wanting romanize Celtic tribes during the 1st century AD it seems that Gaulish individuals who were against romanization built their own community on Evenna island, whereas the right bank's inhabitants wanted to integrate the Empire.[9]

Middle Ages

The independent village

Since the beginning of the Middle Ages, Vienne was being a distinct manor but vassal to the count of Blois, having adopted the name of Vienne-lez-Blois. There was administered by the parish of St-Saturnin, established opposite the present-day city center, on Vienna island. Nevertheless, the presence of diked bridges over the river as well as archaeological excavations demonstrate that both banks have always coexisted with each other. The development of trade on the river and of La Creusille Harbor allowed the village to prosper constantly. Innkeepers, leather-tanners, boatmen and fishermen prospered there at that time. Pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostela (Galicia, Spain) from Paris through Tours stopped here regularly. At the beginning of the 16th century, the construction of a new Blois-Vienne Church began under the orders of Queen Anne of Brittany, but remained unfinished at her death in 1514.

The town of Vienne was mainly built around two axes starting from the Ancient bridge, probably built under Count Odo II of Blois: one running alongside the Loire to the port, before joining the Chartrains bridges driving to Vineuil; the other joining the church then the Treen Cross (Croix Boissée in French) and Les Métairies district to join the St-Michel bridges leading to St-Gervais. These axes still exist through -respectively- the quai Amédée Contant – rue des Ponts Chartrains, and quai Villebois-Mareuil – rue Croix-Boissée – rue de la Croix Rouge – rue des Métairies. The hamlets of Béjun and Bas-Rivière ("Low-River"), located downstream, were populated with a few tenant farms.

Incorporation to Blois main city

The village was integrated into Blois in 1606, under the reign of King Henry IV, when Philip of Béthune, the last manor of Vienne, exchanged it with the royal domain for some land in Sologne. The hamlets of Bas-Rivière and Béjun, on the west of the island, came under the jurisdiction of the commune of Chailles.

By 1657 Gaston, Duke of Orléans, settled on the banks of the Loire river near the church. After his death in 1660 his residence was converted into a hospital.

A new link between Blois and Vienne

During the winter of 1716, the medieval bridge collapsed under the pressure of a violent ice jam break-up on the river. Jacques Gabriel, the architect of King Louis XIV, was commissioned to build a new infrastructure, that would be completed in 1724, and bear his name. He took the opportunity to consolidate the existing levees around the suburb. In 1717, La Bouillie channel was also drained by a dike, thus definitively linking Vienna island to the left bank. In its place, a spillway was created that could be flooded in case of flooding to protect the inhabited areas. The St-Michel and Chartrains bridges were progressively abandoned in favor of the development of practicable roads in the drained marshes.

The construction of a bridge 70 meters upstream from the previous one led Vienne to reconsider its main axes. The road to St-Gervais, renamed President Wilson Avenue (Avenue du Président Wilson in French) in the 20th century, was thus built (at the expense of Rue Croix Boissée) right in the axis of the Jacques-Gabriel Bridge. The avenue was opened in 1776.[10]

After the French Revolution

In the 19th century Vienne had strong difficulty struggling with the successive 100-year floods of the Loire river: first in 1846, then in 1856 (which is the worst of all the floods recorded in Blois since the French Revolution, as nearly 90% of Vienne was under water[11]), and again in 1866.

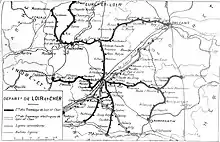

The railroad came to Blois in 1847, so La Creusille Harbor started losing in stake since as people as commodities now would travel faster. From 1886 to 1934, Vienne was served by several steam and electric tramway lines. Even today, one station remains almost as it was in rue Dupré, but the one in rue Ronceraie has been rehabilitated into housing since that time.[12]

In the 1860s, Bloisian painter Ulysse Besnard left his position as director of the municipal museum to devote himself to ceramics in a workshop in Vienne.[13] He was followed by his disciples, basically including: Émile Balon, Alexandre Bigot, Gaston Bruneau, Josaphat Tortat, Adrien Thibault.

During the Franco-Prussian War, the city was occupied, but the suburb was the scene of the assault by Generals Pourcet and Chabron (who left an odonym) from Cheverny.[14] Their victory on 28 January 1871, just a few days before the armistice came into force, allowed the liberation of Blois, despite the bridge being cut and the temporary footbridge being impassable.

During World War II only the western approaches to the bridge were hit by bombing. In 1944, the suburb was used as a refuge for German soldiers after the uprising of Resistance fighters on the right bank on 16 August; Vienne was liberated two weeks later, on 1 September (also odonym).

Modern era

During the 1930s members of the Amar Circus settled in Les Métairies area and left an odonym there.[15] A housing estate, still present today, was built in rue Sourderie.[16] A Bloisian School of Circus (École Blésoise du Cirque in French) still operates in this sector.[17]

In 1970 a second bridge was built over the Loire river to connect Vienne to the right bank in the East, the Charles-de-Gaulle Bridge, then in the West by 1994 with the François-Mitterrand Bridge, both named after the French presidents in office at the time of their inauguration.

In the 1980s construction began in La Bouillie sector. An exhibition center, a racetrack, soccer fields, community gardens and housing were built there. The townhall won its case against the new owners or occupants of these dwellings, who were asked not to invest in this flooding zone since that was a overflow channel. Since then, other facilities have been built within the levees, such as the Aggl'eau swimming pool or the municipal tennis courts.

In 1995 sand mining, then practiced by sifters since the Middle Ages, was banned for being harmful to the river.[18]

Since 2016 Vienne has benefitted from the City Hall's Aménagement Cœur de Ville-Loire (ACVL) development program to redevelop the entire Wilson Avenue. The district is also served by one of the two free shuttle lines set up by the transport company Azalys.

Other projects are currently underway, including the rehabilitation of the former Duke Gaston of Orléans' residence and La Bouillie area.

Geography

Sites of interests

Nowadays the Wilson Avenue is the main shopping axis of the district, crossing it from north-west to south-east, in the continuity of the Jacques-Gabriel Bridge. Blois-Vienne Church is located on a parallel axis, accessible from Rue Croix Boissée. Nearby, the eponymous churchyard is among of the four last ones in whole France,[19] and the former residence of Duke Gaston of Orléans overlooks the Loire river with a remarkable panorama on Blois.

On the Viennese bank the built-up fronts (fronts bâtis in French) bring together all the characteristics of this typical architectural element of the Loire Valley: open onto the river and marked by a bridge, levees, quays, grouped housing, along with a church, and a port.[20] Moreover, those on the Quai Villebois-Mareuil were designed by the Bloisian architect Paul Robert-Houdin,[21] grandson of the magician Jean-Eugène, as part of the post-war reconstructions.

The former La Creusille Harbor was turnt into an urban park along the river and, since 2000, has been listed as a World Heritage site by UNESCO.[22] As part of the heritage of the Loire river more than any other part of Blois, Vienne is naturally part of the programme of La Loire à vélo and the European Rivers Route (EV6).[23] The banks of the Loire are therefore accessible by bike, except in the event of flooding.[24]

For walkers the town hall has installed bronze nails which trace the history of the district through the traditional Viennese streets.[25] Markers of the 1856 and 1866 floods are also present throughout the district (e.g.: around schools, in La Creusille park...).[26]

Many traces of history are visible in Vienne. For example, various timber framing houses are still visible since the Renaissance,[27] or pieces of earthenware on façades.

Wayside crosses and octroi

During the Middle Ages, entrances of Vienne town were often physically indicated by the presence of wayside crosses, as a sign of entry into a parish territory.

In Vienne, there were 4 of these crosses:

- the Fishermen's Cross (La Croix des Pêcheurs in French), at the north-eastern end of Vienne, properly at the exit of La Creusille Park, erected to protect boatmen and fishermen from the river's dangers;

- the Treen Cross (La Croix Boissée in French), which marked the southern entrance to the parish, but the original wooden cross was destroyed during the French Revolution, so a new stoned cross was erected further in the same street;

- the Red Cross (La Croix Rouge in French), indicating the crossroads to go to Bas-Rivière (downstream on Vienna island), or to Saint-Gervais-la-Forêt through the St-Michel bridges; and,

- the Calvary of Low-River's Cross (La Croix du Calvaire de Bas-Rivière in French), indicating the entrance to the hamlet of Bas-Rivière, further in the West of Vienne.

When the parish became proper part of the town of Blois in 1606, an octroi was built at the southern entrance of Wilson Avenue to mark the entrance to the town (and therefore the payment of toll fees).[28]

References

- ↑ Thomas Guillemard; David Josset; Didier Josset (2014). Sanctuaire et quartier antique de Vienne à Blois (PDF) (in French).

- ↑ Hofmann J. Lexicon universale (1698). Blesense Castrum et Pagus Blesensis in Celtica Blesensum (in Latin).

- ↑ Louis Catherine-Bergevin (dir.); Alexandre Dupré (2010). Histoire de Blois V1 – Partie 2 (in French).

- ↑ Georges Touchard-Lafosse (2011). Histoire de Blois et de son territoire, depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours (in French).

- ↑ Pierre Leveel (1981). "Les dénominations «Loire» et «Vienne». Linguistique et histoire »". Société française d'histoire des outre-mers (in French).

- ↑ Barruol G.; Fiches J.-L.; Garmy P. (2008). "Les ponts routiers en Gaule romaine". Suppl. à la Revue archéologique de Narbonnaise (in French). 41: 335–338.

- ↑ Emmanuelle Miejac (1999). "La Loire aménagée: du Moyen Âge à l'époque Moderne entre Cosne-sur-Loire et Chaumont-sur-Loire". Archéologie médiévale (in French). 29: 169–190. doi:10.3406/arcme.1999.937.

- ↑ Stéphane Grivel; Fouzi Nabet; Emmanuèle Gautier; Saïda Temam; Gary Gruwé; Julien Gardaix; Matthieu Lee (2018). "Héritages et influences contemporaines des anciens ouvrages de navigation de la Loire moyenne (France)". Vertigo (in French). 18.

- ↑ Louis de la Saussaye (1833). Essai sur l'origine de la ville de Blois et sur ses accroissements jusqu'au Xe siècle (in French). Hachette Livre. ISBN 978-2-01-450888-8.

- ↑ Archives de la Ville de Blois et d'Agglopolys (2022). "Exposition : Se déplacer en Vienne – Percement de l'avenue Wilson" (in French).

- ↑ "Le jour où Blois-Vienne faillit être englouti par la Loire". La Nouvelle République (in French). 2015.

- ↑ Archives de la Ville de Blois et d'Agglopolys (2022). "Exposition : Se déplacer en Vienne – Les tramways" (in French).

- ↑ "La faïence de Blois : toute une histoire !". La Nouvelle République (in French). 2017.

- ↑ "Janvier 1871, le dernier combat en Loir-et-Cher". La Nouvelle République (in French). 2020.

- ↑ Archives de la Ville de Blois et d'Agglopolys (2022). "Exposition : Particularités viennoises – Cirque Amar" (in French).

- ↑ "Les logements Amar avaient un temps d'avance". La Nouvelle République (in French). 2016.

- ↑ "École Blésoise du Cirque" (in French). Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Noëlle Lizé; Emmanuelle Plumet; Johanne Quéméré (2017). Focus sur Blois : quartier Vienne (in French).

- ↑ Noëlle Lizé; Emmanuelle Plumet; Johanne Quéméré (2017). Focus sur Blois : quartier Vienne (in French).

- ↑ the Val de Loire Official Website (2017). "Les fronts bâtis de Loire". blois.fr (in French).

- ↑ "Sous les tilleuls du quai Villebois-Mareuil". La Nouvelle République (in French). 2017.

- ↑ the Blois City Official Website (2022). "La Creusille Harbour". blois.fr.

- ↑ the Blois City Official Website (2022). "La Creusille Harbour". blois.fr.

- ↑ the Blois City Official Website (2022). "The Loire in Blois". blois.fr.

- ↑ "Sillonner Blois en restant dans les clous". La Nouvelle République (in French). 2015.

- ↑ Matthieu Renard (2021). "L'histoire de la Loire inscrite sur les murs à Bloiss". La Nouvelle République (in French).

- ↑ Clément Alix; Julien Noblet (2013). "Les maisons en pan de bois de Blois : réévaluation du corpus d'une ville ligérienne XVe-XVIe siècle". Presses universitaires François-Rabelais (in French).

- ↑ Noëlle Lizé; Emmanuelle Plumet; Johanne Quéméré (2017). Focus sur Blois : quartier Vienne (in French).