| Bloody New Year | |

|---|---|

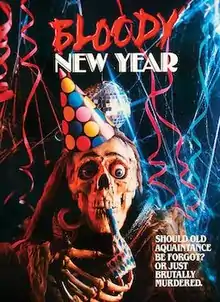

US video cover | |

| Directed by | Norman J. Warren |

| Screenplay by | Frazer Pearce |

| Produced by | Hayden Pearce |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John Shann |

| Edited by | Carl Thomson |

| Music by | Cry No More Nick Magnus |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Bloody New Year (also known as Time Warp Terror and Horror Hotel)[1] is a 1987 British supernatural horror film directed by Norman J. Warren and starring Suzy Aitchison, Nikki Brooks, Colin Heywood, Mark Powley, Catherine Roman and Julian Ronnie. The plot concerns a group of teenagers who are trapped in a haunted hotel on a remote island.

Shot in Wales, the film features an electronic score composed by Nick Magnus as well as seven songs by Magnus and Chas Cronk's band Cry No More. It was released direct-to-video in September 1987 in the United Kingdom and October 1987 in the United States.

Plot

In 1959, a group of partygoers celebrate New Year's Eve at the Grand Island Hotel before mysteriously vanishing.

Decades later, a group of teenagers – couples Lesley and Tom and Janet and Rick, with their friend Spud – are spending the day at a seaside funfair when they see a trio of hooligans – Dad, Ace and The Bear – terrorising an American tourist named Carol. They rescue Carol and escape the thugs by taking a boat out to sea, only to run aground and end up stranded on Grand Island. They stumble across the hotel, which appears deserted; the lobby is adorned with Christmas decorations, despite the fact that it is July.

Spud looks for a towel for Carol, who is damp and shivering. While he is gone, the apparition of a maid enters and gives Carol a towel. Meanwhile, Spud hears music coming from the ballroom. He sees a duo performing on stage only for them to vanish before his eyes. In one of the guestrooms, Janet and Rick swap their ruined clothes for 1950s attire. Janet is horrified by the sudden appearance of a disfigured woman in a mirror. While searching for the building's circuit breakers, Lesley and Tom are startled by fireworks that inexplicably ignite. The teens regroup and find the hotel's empty theatre, which is screening the film Fiend Without a Face. Rick, convinced that someone is staging an elaborate prank, tries to turn off the projector but inadvertently plays a promotional reel for the hotel showing partygoers in front of the entrance. One of the figures bursts through the screen, kills Spud, and vanishes.

Desperately trying to find a way off the island, the survivors separate and are each plagued by supernatural happenings: Lesley and Tom find a cottage near the shore, where Lesley is attacked by a monstrous figure that disappears after Tom spears it; Janet and Rick hear disembodied voices in the woods and see a plane crash into a nearby building; and Carol is suddenly caught in a snowstorm inside the hotel. Lesley summons the group to the cottage to find Tom. There, they are attacked by the three hooligans, who have followed the group to the island in another boat. Dad kills Lesley by impaling her through the abdomen, upon which she transforms into a zombie. She kills Dad by throwing him out of a window, then The Bear by twisting his head around and breaking his neck. Meanwhile, Janet is attacked by a banister carving that comes to life. Rick takes an old shotgun and shoots Lesley, seemingly killing her.

An injured Tom returns to the hotel and is cared for by Janet. Rick and Carol search for the hooligans' boat and discover the site of another plane crash. Tom transforms into a zombie and attacks Janet, who runs to the hotel's lift with Tom in pursuit. Tom is killed when the rising lift traps and severs his arm, while a featureless figure envelops Janet and absorbs her into the walls of the lift. Elsewhere, Carol and Rick witness more apparitions and poltergeist activity, and Ace is killed in the kitchen after falling into a large vat.

Carol and Rick flee to the ballroom, where they are greeted by a woman resembling the zombified Lesley. She tells them that they are trapped in a time warp created when an aircraft carrying an experimental cloaking device crashed on the island on New Year's Eve, 1959. Carol and Rick flee the hotel, pursued by their friends and the hooligans – all now resurrected as zombies. They make it to the shore and Carol manages to board the hooligans' boat, but Rick is trapped in quicksand and killed by the zombified Dad, who slices his head with an outboard motor propeller. Carol is pulled through the floor of the boat and into the water by an unseen force. She emerges behind a mirror in the ballroom, where her friends and the hooligans, now restored to their original appearances, are happily joining in the New Year celebrations. As the picture fades to black, a woman's scream is heard.

Cast

- Suzy Aitchison as Lesley

- Nikki Brooks as Janet

- Colin Heywood as Spud

- Mark Powley as Rick

- Catherine Roman as Carol

- Julian Ronnie as Tom

- Steve Emerson as "Dad"

- Steve Wilsher as "Ace"

- Jon Glentoran as "The Bear"

- David Lyn as TV Interviewer

- Val Graham as Housemaid

- Jenny Bayliss as Madame Zelda

- Steve Edison as Film Invader

- Rory Maclean as 1st Expert

- Nick Dowsett as 2nd Expert

- Roy Hill as Flying Cadillacs

Rock musicians Chas Cronk and Tony Fernandez (representing Cronk's band Cry No More) appear as the ghostly singers seen by Spud. Emerson also served as the film's stunt coordinator.[2]

Production

Development

Warren was approached by Maxine Julius to make a horror film for her and developed the plot over seven days with line producer Hayden Pearce.[3] Bloody New Year was meant as a homage to 1950s B movies, the film being set on an island trapped in a time warp where it is always New Year's Eve, 1959.[3] Originally the entire film was to have been set in the 1950s, but this idea was abandoned due to budget constraints.[1] According to Warren, the premise was inspired by the real-life contamination of a Scottish island as the result of a failed disease control experiment.[1]

Filming

Bloody New Year was filmed in June.[2] It was shot mostly in and around the seaside resort of Barry Island in South Wales, with Friars Point House serving as the filming location for the Grand Island Hotel.[3] The fairground scenes were filmed at Barry Island's long-running funfair with minimal supervision from the owners, who gave the crew full use of the site and its attractions at a cost of £300 (equivalent to £935 in 2021) for a week's shooting.[4] To secure extras for these scenes, the crew offered free rides to members of the public. The ballroom scenes were filmed at The Paget Rooms theatre in Penarth and the scenes of Janet's death in a disused tower block.[2]

The film's opening credits play over black-and-white footage presenting the 1959 Grand Island Hotel New Year's Eve party. The extras playing the dancing hotel guests were members of a local rock 'n' roll preservation society and worked unpaid.[2] The extracts from Fiend Without a Face were supplied free by its producer, Richard Gordon, a friend of Warren who had produced his earlier film Inseminoid.[2] A stunt scene in which the character Rick opens the back door of a cottage only to find himself dangling over a cliff edge was performed by actor Mark Powley without safety equipment.[2]

Music

The electronic musical score for Bloody New Year was composed by Nick Magnus. The film features seven songs by Magnus and Chas Cronk's band Cry No More: "Recipe for Romance" (which accompanies both the opening and closing credits), "Boys Don't Cry", "Caveman Rock", "Jenny", "You're Not Fooling Me", "Every Single Time" and "When Love Is Not Enough".

Release

Bloody New Year was released on video in September 1987 in the UK and on 22 October 1987 in the US.[5][6][7]

Censorship

Warren had envisaged a particularly bloody scene for the film's climax, where the zombified "Dad" (Steve Emerson) kills Rick by slicing his head with an outboard motor propeller. Ultimately the violence was toned down to ensure that the British Board of Film Classification would award the film a 15 certificate instead of a more restrictive 18.[2]

Critical response

Kim Newman describes the film as a "feeble dump-bin video quickie".[8] Dennis Schwartz, in his review for Ozus' World Movie Reviews, calls it a "goofy film" with "brutal" dialogue, "cheesy" direction and "not much plot".[9] According to Jake Dee of JoBlo.com, the film's "cheap and silly" practical effects are reminiscent of a "fun early Herschell Gordon Lewis movie". Dee adds that the film "plays like a haunted house flick in the interiors and a traditional zombie flick in the exteriors, with the middle ground a breeding place for the genuinely odd and unsettling amalgamation of both."[10]

AllMovie gives Bloody New Year one star out of five. Commentator Cavett Binion writes that the film employs a "wacky but interesting supernatural theme" with "silly special effects". He considers it "derivative of Sam Raimi's The Evil Dead and Lucio Fulci's The Beyond, minus those films' extreme approach to horror".[11] Writing for Video Watchdog magazine, Richard Harland Smith describes the film as a "barrel-scraping rehash of horror tropes from Shock Waves (creepy island hotel), Dawn of the Dead (bickering TV commentators), The Evil Dead (girl-next-door turned cackling, whey-faced ghoul) and even Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo." He adds that while the premise is reasonable, the film fails to "[particularise] the horror beyond a few double exposure ghosties and some haunted hardware."[12]

Preston Barta of the Denton Record-Chronicle remarks that Bloody New Year "could perhaps be best described as an episode of Scooby-Doo that is sent through the filter of The Shining and The Evil Dead", adding that in some places "it's got early Sam Raimi written all over it." He criticises various aspects of the film: "The drama is no good, the characters are all jerks (so it's OK that they kick the bucket) and the dialogue is elementary."[13] Writing for Sight & Sound magazine, Anne Billson compares the film to the Japanese horror comedy House (1977) and its production values to those of "early Doctor Who".[14]

Aftermath

Warren commented negatively on the film. In one interview, he described Bloody New Year as "a very terrible experience for me; in fact it turned out to be a bloody nightmare. We had the wrong producers on that film and they didn't know anything about horror. So the film lacks in every department and by the end of it, my heart just wasn't in it." He added that the producers "wanted to make the film cheaply and terribly quick" and that this was to the detriment of the music and sound effects.[15] In another interview, Warren criticised the music, stating that it "just doesn't work". He added: "On the second day of dubbing, I must confess I gave up on the film. I'd run out of fight, and just sat there and let them go through the motions."[16] Warren said that his experiences on Bloody New Year put him off making any more films.[17]

References

- 1 2 3 Duvoli, John (December 1987). "King of the Video Nasties". Fangoria. Vol. 7, no. 69. New York City, New York: O'Quinn Studios. pp. 14–15. ISSN 0164-2111. OCLC 46637019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Warren, Norman J. (2019). "Bloody New Year" DVD audio commentary. Vinegar Syndrome. 814456021911 (EAN); VS-258.

- 1 2 3 Fischer, Dennis (2011). Science Fiction Film Directors, 1895-1998. McFarland & Company. pp. 650–651. ISBN 978-0786460915.

- ↑ Warren, Norman J. (5 April 2018). "Interview No. 721". historyproject.org.uk (Transcript). Interviewed by Martin Sheffield. British Entertainment History Project. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ↑ Botting, Josephine. "Warren, Norman J. (1942–)". Screenonline. London, UK: British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ↑ Hayward, Anthony (1988). "Video Releases". Film Review 1988-9. Columbus Books. p. 158. ISBN 0-86287-939-6.

- ↑ "Horror". The Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach, Florida. 16 October 1987. p. 22 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Newman, Kim (2011) [1988]. Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s (revised ed.). London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4088-0503-9.

- ↑ Dennis Schwartz (28 March 2016). "Bloody New Year (Time Warp Terror)". Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ↑ Dee, Jake (3 January 2020). "The F*cking Black Sheep: Bloody New Year (1987)". JoBlo.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ Binion, Cavett. "Bloody New Year (1987)". AllMovie. San Francisco, California: All Media Network. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ↑ Harland Smith, Richard (April 2005). "Dog Bytes". Video Watchdog. No. 118. Cincinnati, Ohio: Lucas, Tim and Lucas, Donna. p. 5. ISSN 1070-9991. OCLC 646838004.

- ↑ Barta, Preston (8 February 2019). "Reviews: Scream Factory Releases Valentine in Conjunction with Lovers' Holiday". Denton Record-Chronicle. Denton, Texas: Patterson, Bill. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ↑ Billson, Anne (September 2019). James, Nick (ed.). "Ham, Hammer, Hammest". Sight & Sound. Vol. 29, no. 9. London, UK: British Film Institute. p. 86. ISSN 0037-4806. OCLC 733079608.

- ↑ "Interview: Director Norman J. Warren on Inseminoid, Prey ... and Bloody New Year!". buzzexpress.co.uk. 31 December 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017.

- ↑ Locks, Adam (April 2009). "Satan Chic: An Interview with Cult British Horror Director Norman J. Warren". Senses of Cinema. Melbourne, Australia. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ↑ Bayley, Bruno. "Norman J. Warren". vice.com. New York City, New York: Vice Media. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2019.