Boğdan Sarayi (Turkish for "Palace of Bogdania (Moldavia)") was an Eastern Orthodox church in Turkey's largest city, Istanbul. Erected in the Byzantine era, its original dedication is unknown. In the Ottoman era the small edifice, being dedicated to St. Nicholas of Myra, was known as Agios Nikólaos tou Bogdansarághi (Greek: Ἅγιος Νικόλαος τοῦ Βογδανσαράγι).[1][2] and was part of the Istanbul residence of the Moldavian hospodar′s legation to the Ottoman Porte.[1][2] The building – whose parts above ground have almost completely disappeared – is a minor example of Byzantine architecture in Constantinople.

Location

The remains of the church lie in Istanbul, in the district of Fatih, in the neighborhood (Turkish: Mahalle) of Salmatomruk, not far from Edirnekapı (the ancient Gate of Charisius), 250 m. east of the museum of Chora and 100 m north of the Kefeli Mosque, both former Byzantine religious buildings.[1] The ruins of the edifice are hardly accessible, as of 2012, as they are enclosed in a tire shop at Draman Caddesi 32.[3]

History

Byzantine Age

The building was erected on the slope of the sixth hill of Constantinople which overlooks the Golden Horn. Nothing is known about the edifice in the Byzantine Age, but due to its position it was likely an annex of the monastery of St. John the Baptist in the Rock (Greek: Ἅγιος Ιωάννης Πρόδρομος ἐν τῇ Πὲτρα, pr. "Hagios Ioannis Prodromos en ti Petra"), one of the largest monasteries of Constantinople, where, among other relics, the instruments of the Passion of Christ were kept.[4] Nevertheless, due to its small dimensions it is not likely that the building was the katholikon (main church) of the monastery.[4] According to some sources it was erected in twelfth century, during the Komnenian age,[1][5] while for others it is a Palaiologan foundation of the fourteenth century.[2] Its north–south orientation shows that it was originally erected not as a church, but rather as a funerary chapel.[1][2]

Ottoman Age

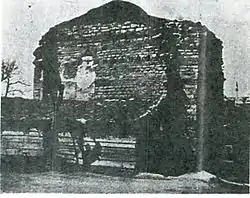

After the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, in sixteenth century the chapel became part of the large land estate bought by the voivode/hospodar of Moldavia to host his envoys in Istanbul, and named accordingly Boğdan Sarayi ("Moldavian Palace").[6][1][5] In this respect, its usage as private chapel of a patrician house represents a rarity in the Ottoman city. At the beginning of the eighteenth century the complex – a coveted property because the high border wall protected it from fires – was leased by the Sultan as residence for several foreign envoys, among them the Swedish ambassadors to the Ottoman Porte P. Strasburg and C. Rolomb, who sojourned in Istanbul in 1634 and 1657/58 respectively.[2] In June 1760 the Phanariote John Callimaches endowed it to the Russian monastery of St. Pantaleon on Mount Athos.[4] The complex burned down in the fire of 1784, and afterward the land was only used as a market garden.[2] The possession of the church by the Athos monastery was confirmed again by relatives of Callimaches in January 1795 and August 1814, but the Russian monks showed little interest in the church's restoration, possibly because of the state of war between the Russian Empire and the Sublime Porte.[4] In the nineteenth century the edifice steadily decayed and after the 1894 Istanbul earthquake fell into ruin. In 1918 a German archaeologist pursued clandestine excavations and found in the crypt three unnamed tombs.[4] In the second half of the 20th century the remains of the building were enclosed in a shanty (Turkish: Gecekondu), and today—lying inside a tire shop—they are hardly accessible.[7] As of 2012 the parts above ground have almost disappeared, and only the crypt still exists.[4]

Description

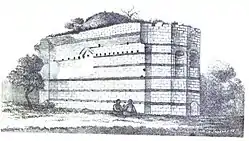

The edifice had a rectangular plan, with sides of 6.20 m and 3.50 m,[1] and was originally composed of two storeys, consisting of an above ground chapel and a subterranean crypt.[2] The chapel was surmounted by a dome with pendentives insisting on two transverse arches across the walls, and ended towards North with a Bema and a polygonal apse adorned externally with niches, while the crypt was surmounted by a barrel vault and had also a simple apse.[2] The edifice's brickwork consisted of courses of three or four rows of white stones alternating with a row of red bricks, obtaining a chromatic effect typical of the late Byzantine period. Its north–south orientation suggests the building's use as a funerary chapel, rather than as a church, since churches in Constantinople were almost always oriented in east–west direction.[2] The attested past existence of remains of walls perpendicular to the structure indicates the possibility that this was part of a larger complex, most likely the monastery of St. John of Petra, one of the largest monasteries of Constantinople.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Janin (1953), p. 384

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 108.

- ↑ "Archaeological Destructıon in Turkey, preliminary report" (PDF), Marmara Region – Byzantine, TAY Project, p. 45, retrieved April 3, 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Janin (1953), p. 385

- 1 2 Mamboury (1953), p. 255

- ↑ G. Balş, Buletinul Comisiunii Monumentelor Istorice, București, 1916, p.10.

- ↑ King (1999), p. 17

Sources

- Mamboury, Ernest (1953). The Tourists' Istanbul. Istanbul: Çituri Biraderler Basımevi.

- Janin, Raymond (1953). La Géographie Ecclésiastique de l'Empire Byzantin. 1. Part: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique. 3rd Vol. : Les Églises et les Monastères (in French). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 9783803010223.

- King, Charles (1999). The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 978-0817997922.