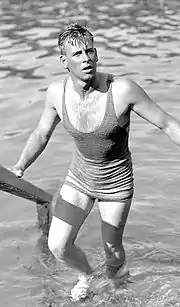

Charlton c. 1930 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Andrew Murray Charlton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | "Boy" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National team | Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 12 August 1907 Crows Nest, Sydney | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 December 1975 (aged 68) Avalon, Sydney | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.83 m (6 ft 0 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Swimming | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strokes | Freestyle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Club | Manly Swimming Club | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Andrew Murray "Boy" Charlton (12 August 1907 – 10 December 1975) was an Australian freestyle swimmer of the 1920s and 1930s who won a gold medal in the 1500 m freestyle at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris. He set five world records and also won a further three silver and one bronze medal in his Olympic career.[1]

Early life

.jpg.webp)

Charlton was born in Crows Nest, Sydney, as the only son of Oswald and Ada Charlton. The accounts of his early life vary: the Australian Dictionary of Biography states that his father was a bank manager, while other sources suggest that he was raised in low socio-economic conditions and relied on benefactors to support his career. He was raised in the northern seaside suburb of Manly and was educated at Manly Village Public School and later Sydney Grammar School. Charlton was a member of North Steyne Surf Life Saving club in his teens, before transferring to Manly Life Saving Club in the mid 1920s[2]

Swimming

Charlton first came to public attention in 1921 when he won a 440 yd freestyle race in the open division at a New South Wales Swimming Association competition in 5 min 45 s. It was his youth that led to his nickname "Boy". In 1922 Bill Harris, the bronze medallist in the 100m freestyle at the 1920 Summer Olympics, came to Australia from Honolulu to compete against the likes of Frank Beaurepaire and Moss Christie. Charlton defeated Harris at the New South Wales Championships, winning the 440 yd in 5 min 22.4 s. He then set a world record of 11m 5.4s in the 880yd event, as well as winning the one mile race in 23 min 43.2 s. Charlton used a trudgen stroke which embodied characteristics of the modern crawl stroke, which was at the time in its infancy.[3]

In 1923, the 15-year-old Charlton swam for the first time against Beaurepaire, who had won 35 Australian championships and had set 15 world records in his career. The Manly Baths was filled to capacity for the 440 yd race, with Charlton winning the race by two yards in a time of 5m 20.4s, which led to Beaurepaire predicting that fitness permitting, Charlton would break world records in 1924.

The start of 1924 in Australia was highlighted by the arrival of Swedish swimmer Arne Borg, at the time the holder of four world records, to compete against the 16-year-old Charlton in the 440yd freestyle at the New South Wales Championships. The Domain Baths were filled to capacity with between 5000 and 8000 spectators, 400m queues forming outside the venue. Borg held the lead for the first half of the race until Charlton drew level, taking the lead at the 320yd mark. Charlton eventually won by 20yds to equal Borg's world record of 5 min 11.8 s. Charlton was given a lap of honour as Borg rowed him around the pool in a small boat.[4] They again met in the 880yd and 220yd events, with Charlton winning the former in a world record time of 10 min 51.8 s and the latter in an Australian record of 2 min 23.8 s.

Three Olympics

Charlton was selected for the Australian team for the 1924 Summer Olympics and travelled to Paris by sea with his coach, Tom Adriann, who was also appointed the team coach. On the way, Adriann suffered a nervous breakdown, and threw himself overboard. Even though Adriann was rescued, he was left in London while the team travelled to Paris without a coach.

Then, while in Paris, Charlton competed in his first event, the 1500 m freestyle. He won both his heat and his semi-final, qualifying for the final, where he lined up against Borg and Beaurepaire. In the final, Borg immediately claimed the lead and maintained it until the 300 m mark, when Charlton moved alongside him. Charlton forged ahead to lead by 5 metres at the 600 m, before proceeding to defeat Borg by 40 m, while lapping the remainder of the field to win gold in a new world record time of 20m 6.6s. In the 400 m freestyle, Charlton again lined up against Borg and Johnny Weissmuller of the United States. Charlton progressed to the final, finishing second to Weissmuller in both his heat and semi-final. In the final, Charlton, the distance specialist, trailed far behind as Borg and Weissmuller contested the lead. Charlton was eight metres behind at the 150 m mark, before making his move. However, he left it too late and finished a metre behind the leaders, finishing with the bronze medal. Charlton then combined with Ernest Henry, Moss Christie and Beaurepaire to claim silver in the 4 × 200 m freestyle relay behind the United States. Although Charlton had claimed the lead from the Americans in the second leg, the two following Australians were overwhelmed, losing by nine seconds, with the Americans setting another world record.

Physiologists had become involved in sport at the time of the Paris Olympics and Charlton's lung capacity was tested with a machine, which blew mercury through a set of bent tubes. They could not believe his lung capacity. It was the highest lung capacity of anyone they had rated at that time – only 16 years of age.

After the games, Charlton declared that swimming would take a back seat to his study and work career, and declined offers to tour the US and Europe. However, he still won the 200 m, 400 m and 800 m events at the Tailteann Games. He resumed studies at Hawkesbury Agricultural College, but did not graduate and subsequently became a station-hand at Kurrumbede station in Gunnedah, in western New South Wales. Charlton limited his training to irregular visits to Sydney, when he consulted his coach, former Olympic medallist Henry Hay.

After a two-year absence from competition, he returned to the New South Wales championships in 1927, setting a world record of 10m 32s in the 880 yd (800 m) on his return. He was again victorious in the 440 yd (400 m) in an Australian record time of 4 min 59.8 s. Charlton again returned to his inland job in Gunnedah before returning to Sydney the following year to secure qualification for the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam by winning the 440 yd (400 m) New South Wales championships.

In Amsterdam, in the 1500 m, Charlton finished second behind Borg in his heat, before trailing Buster Crabbe home in the semi-final. Borg went on to set a new Olympic record to defeat Charlton by 15 m. In the 400 m, Charlton again finished second in both his heat and semi-final. He again claimed the silver medal, finishing behind Argentina's Alberto Zorrilla.

In total, Charlton won five Olympic medals, which was a record until 1960.

After shelving his swimming career on his return to Australia for four years, Charlton again broke the Australian record in both the 440 and 880 yd (800 m) freestyle events at the 1932 New South Wales championships to gain selection for the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, the oldest member of the team at 25 years of age. He contracted influenza a fortnight before the Games after arriving in the United States. Charlton raised hopes that he had recovered when he won his heat, but then only won third place in the semi-final, although he still progressed to the final of the 400 m freestyle. Charlton finished in a distant sixth, some ten seconds behind the winner. In the 1500 metres, Charlton finished second in his heat, before coming fifth in his semi-final, resulting in his elimination.

While in Los Angeles, Charlton was offered the chance to audition in Hollywood. Weissmuller had done 12 "Tarzan" movies and was now Jungle Jim. But he turned down the offer because he didn't fancy swimming around, with his head out of the water, looking for baboons and alligators and things chasing him.

After swimming

Charlton retired from swimming upon his arrival in Australia, and in 1934 he opened a pharmacy business in Canberra. In 1936 he returned to the land, raising sheep near Tarago, New South Wales. He married on 20 March 1937[5] and settled on a 12,000-acre (49 km2) property near Goulburn, where he had a son and daughter. He was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame as an "Honour Swimmer" in 1972.[6] There are two swimming pools in Sydney that have been named after Charlton; Sydney Domain Baths were renamed in his honour and the swim centre in Manly was also renamed the Andrew "Boy" Charlton Pool.[3][7]

Death

Charlton died in Sydney of a heart attack at the age of 68. His son, Murray Charlton, said on ABC's Australian Story, he "probably smoked up until the last five years of his death, but he had emphysema, so really, once he got emphysema, he couldn't even smoke. Er, that was the irony of it. And he yeah, it was certainly what killed him in the end. I mean, yeah. Which was, I thought, was very sad, coming from a world champion, to die of cigarettes. It was very sad, I thought. It's like the gods… I mean, if you're a wonderful artist, they usually take your sight away. And I think that's probably what they did with him, in that they took these wonderful lungs away with cigarettes."[8]

See also

References

- ↑ "Boy Charlton". Olympedia. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ↑ North Steyne SLSC Annual Report 1924

- 1 2 Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Boy Charlton". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020.

- ↑ "SWIMMING". The Argus. Melbourne. 14 January 1924. p. 12. Retrieved 7 July 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Andrew 'Boy' Charlton marries at St Marks in Sydney, 20 March 1937. gettyimages.co.uk

- ↑ "Andrew M. "Boy" Charlton (AUS)". ISHOF.org. International Swimming Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Swim Centre. manly.nsw.gov.au

- ↑ A Man Called Boy, Australian Story, ABC Television, 5 June 2006

Bibliography

- Andrews, Malcolm (2000). Australia at the Olympic Games. Sydney, NSW: ABC Books. pp. 85–88. ISBN 0-7333-0884-8.

- Howell, Max (1986). Aussie Gold. Albion, Queensland: Brooks Waterloo. pp. 39–44. ISBN 0-86440-680-0.

External links

- Australian Dictionary of Biography

- Andrew Charlton at the Australian Olympic Committee (archive)

- Andrew Charlton at Olympics.com

- Andrew Charlton at Olympic.org (archived)

_Charlton_Pool.jpg.webp)