| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

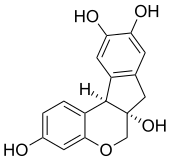

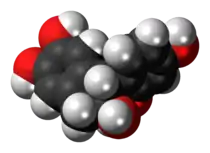

| Preferred IUPAC name

(6aS,11bR)-7,11b-Dihydroindeno[2,1-c][1]benzopyran-3,6a,9,10(6H)-tetrol | |

| Other names

Brasilin; Natural Red 24; CI 75280 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 4198570 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.799 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H14O5 | |

| Molar mass | 286.283 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Brazilin is a naturally occurring, a homoisoflavonoid, red dye obtained from the wood of Paubrasilia echinata, Biancaea sappan, Caesalpinia violacea, and Haematoxylum brasiletto (also known as Natural Red 24 and CI 75280).[1] Brazilin has been used since at least the Middle Ages to dye fabric, and has been used to make paints and inks as well. The specific color produced by the pigment depends on its manner of preparation: in an acidic solution brazilin will appear yellow, but in an alkaline preparation it will appear red. Brazilin is closely related to the blue-black dye precursor hematoxylin, having one fewer hydroxyl group. Brazilein, the active dye agent, is an oxidized form of brazilin.[2][1]

Sources of brazilin

Brazilin is obtained from the wood of Paubrasilia echinata, Biancaea sappan (Sappanwood), Caesalpinia violacea, and Haematoxylum brasiletto.[1] The sappanwood is found in India, Malaysia, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, the latter being a major supplier of the wood to Europe during the early Middle Ages. Later, discovery of brazilwood (Paubrasilia echinata) in the new world led to its rise in popularity with the dye industry and eventually its over-exploitation. Brazilwood is now classified as an endangered species.[3]

Extraction and preparation

There are many ways to extract and prepare brazilin. A common recipe, developed in the Middle Ages, is to first powder the brazilwood, turning it into sawdust. Then, the powder can be soaked in lye (which produces a deep, purplish red) or a hot solution of alum (which produces an orange-red color), either of which extracts the color better than plain water alone. To the lye extract, alum is added (or to the alum extract, lye) in order to fix the color, which will precipitate from the solution. The precipitate can be dried and powdered, and is a type of lake pigment.

Like many lake pigments, the exact colors produced depends on the pH of the mixture and the fixative used. Aluminium mordants used with brazilin produce the standard red colors, while the use of a tin mordant, in the form of SnCl

2 or SnCl

4 added to the extract is capable of yielding a pink color.

An alternative preparation which produces a transparent red color involves soaking the brazilwood powder in glair or a solution of gum arabic. Alum is added to help develop and fix the color, which can then be used as a transparent ink or paint.

As with hematein, brazilin can be used for staining cell nuclei in histological preparations when combined with aluminium. The nuclei are then colored red instead of blue.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Dapson RW, Bain CL (2015). "Brazilwood, sappanwood, brazilin and the red dye brazilein: from textile dyeing and folk medicine to biological staining and musical instruments". Biotech Histochem. 90 (6): 401–23. doi:10.3109/10520295.2015.1021381. PMID 25893688.

- ↑ De Oliveira, Luiz F.C.; Edwards, Howell G.M.; Velozo, Eudes S.; Nesbitt, M. (2002). "Vibrational spectroscopic study of brazilin and brazilein, the main constituents of brazilwood from Brazil". Vibrational Spectroscopy. 28 (2): 243. doi:10.1016/S0924-2031(01)00138-2.

- ↑ Varty, N. (1998). "Caesalpinia echinata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998: e.T33974A9818224. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T33974A9818224.en.

References

- The Merck Index, 12th Edition. 1392

- Armstrong, Wayne P. (1994). "Natural Dyes". HerbalGram. 32: 30.

- Thompson, Daniel V. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting, Dover Publications, Inc. New York, NY. 1956.