A breakout is a military operation to end a situation of investment (being surrounded) by offensive operations that achieve a breakthrough—escape from offensive confinement. It is used in contexts such as this: "The British breakout attempt from Normandy".[1] It is one of four possible outcomes of investment, the others being relief, surrender, or reduction.

Overview

A breakout is achieved when an invested force launches an attack on the confining enemy forces and achieves a breakthrough, meaning that they successfully occupy positions beyond the original enemy front line and can advance from that position toward an objective or to reunite with friendly forces from which they were separated.

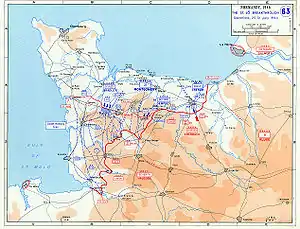

To be categorized a breakout, an invested force is not necessarily required to be completely encircled by an enemy force. Rather, they may have their movement partially restricted by a terrain feature or potentially the use of an area denial weapon such as the VX nerve agent.[2] That was the case in 1944 in the Saint Lo Breakout in which a large portion of the force's movement was restricted by water and not in fact by enemy positions.[3]

While that may be true of a beachhead, it is not necessarily true of a bridgehead.[2] If the bridge is sufficient in capacity compared to the size of the force and does not significantly restrict its movement, it does not represent a sufficient barrier for the force to be considered encircled. Similarly, open water may not be a barrier in the same right.

Consider a small detachment of marines with more than sufficient amphibious transports and a significant military presence at sea, such as the beginning stages of the Gallipoli Campaign of the First World War. Had they evacuated to sea, they would retain a significant military presence, as they were principally a naval military force. Conversely, consider the military evacuation of British troops at Dunkirk during the Second World War. The force clearly was pressed by the enemy, and it broke out but lost their effective strength as a fighting force. It was, at the base of it, a land force escaping, not an amphibious force maneuvering.[4]

The key feature is the loss of freedom of maneuver. If a force can easily overcome a terrain feature and maintain its fighting strength, it is not breaking out but maneuvering in the same way that any force would over nonrestrictive terrain.

A breakout attempt need not result in a breakthrough, such as the 4th Panzer Army suffered during Operation Winter Storm or the British 1st Armored Division suffered at Campoleone.[5] That is referred to as a failed breakout. A breakout may be attempted in conjunction with relief, which may be essential especially if the invested force has already experienced failed breakout attempts (again, as in Winter Storm).

First World War

As the situation on the Western Front during the First World War has been widely regarded as a single continent-long siege, rather than a series of distinct battles, it is possible to consider offensive action from the Allies as a type of breakout. [6][7] In that sense, the Allied armies may be considered encircled, albeit on a hitherto-unheard of scale, with the German army to their east, the Alps and the Pyrenees to their south, and the sea to their west and north. Indeed, as the Dunkirk evacuation illustrated, despite having by far the largest navy in the world, those armies' amphibious movements were nearly impossible logistically. [8] [9] Similarly, as is seen at the Battle of Sarikamish, mountainous terrain remained a significant obstacle to military movement and could inflict numerous casualties.[10]

Strategy and tactics

The classic breakout strategy involves the concentration of force at one weak point of the encircling force.[11] In the case of the Battle for North Africa, a variation of the tactic was used by German Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, who secured both his flanks before quickly penetrating into the enemy's rear.[11] During the Second World War, British General Bernard Montgomery also adopted the strategy by attacking the enemy's narrow front.[12]

Breakout maneuvers, despite their own myriad risks, may become necessary by a number of disadvantages encircled forces suffer:[13]

- They are vulnerable to concentrated artillery fire.

- They are vulnerable to use of weapons of mass destruction.

- They, at some point, exhaust their supplies if resupply is not possible by air.

- They cannot evacuate the dead and the wounded.

- They are vulnerable to loss of morale and discipline.

The invested force suffers from the disadvantages resulting from occupying a confined space and also from those resulting from a lack of resupply. Therefore, the encircling force has a significant tactical advantage and the advantage of time. It may, in fact, choose to not engage their enemy at all and simply wait it out, leading to eventual exhaustion of ammunition if the invested force gives battle or to the eventual exhaustion of food and water otherwise.[14][15][16]

The US Army lists four conditions, one of which normally exists when a force attempts a breakout maneuver:

- The commander directs the breakout or the breakout falls within the intent of a higher commander.

- The encircled force does not have sufficient relative combat power to defend itself against enemy forces attempting to reduce the encirclement.

- The encircled force does not have adequate terrain available to conduct its defense.

- The encircled force cannot sustain long enough to be relieved by forces outside the encirclement. [17]

Of necessity, the broad concept is subject to interpretation. In The Blitzkrieg Myth, John Mosier questions whether the concept as applied to tank and other warfare in the Second World War was more misleading than helpful to planning, on account of the numerous exceptional conditions faced in war and also whether evaluation based largely on how well breakout or breakthrough potential was realized is appropriate[18]

Examples

An example is the battle of Hube's Pocket on the Eastern Front in the Second World War in which the German First Panzer Army was encircled by Soviet forces but broke out by attacking westward and linking with the II SS Panzer Corps, which was breaking into the encirclement from outside. The breakout effort focused on the west because it was thinly held by the 4th Tank Army.[19] The maneuver was an improvisation after Soviet General Georgy Zhukov concentrated his blocking forces southwards, where the German breakout had been anticipated.[19] The German forces escaped relatively intact.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ Badsey, Stephen (1990). Normandy 1944: Allied Landings and Breakout. Osprey Campaign Series 1. Botley, Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-85045-921-0.

- 1 2 Army Field Manual FM 3-90 (Tactics) p. D-0

- ↑ Blumenson, Martin (2012) Breakout and pursuit. Whitman Pub Llc

- ↑ Thompson, Julian (2013)Dunkirk: Retreat to victory. Skyhorse Publishing Incorporated.

- ↑ "ANZIO 1944". Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "The National Archives - Education - The Great War - Lions led by donkeys? - Gallipoli - Background". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Heuser, Beatrice (2010) The evolution of strategy: Thinking war from antiquity to the present. Cambridge University Press. p. 82

- ↑ Friedman, Norman (2011) Naval weapons of world war one. Seaforth Publishing. p. 8

- ↑ Lord, Dunkan (2012) The miracle of Dunkirk. Open Road Media

- ↑ Levene, Mark (2013). Devastation: Volume I: The European Rimlands 1912-1938. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-19-968303-1.

- 1 2 Piehler, G. Kurt (2013). Encyclopedia of Military Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. p. 1393. ISBN 978-1-4129-6933-8.

- ↑ Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. New York: Random House Publishing Group. p. 367. ISBN 978-1-4000-6693-3.

- ↑ Army Field Manual FM 3-90 (Tactics) p. D-9

- ↑ Wykes, Alan (1972), The Siege of Leningrad, Ballantines Illustrated History of WWII

- ↑ "The Mighty Roman Legions: Starving a City Into Submission With Siege Tactics". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "The History Reader - A History Blog from St. Martins Press". The History Reader. 18 May 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Army Field Manual FM 3-90 (Tactics) p. D-10

- ↑ Mosier, John (2003). The Blitzkrieg Myth. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-000977-2 (pbk.)

- 1 2 3 Forczyk, Robert (2012). Georgy Zhukov. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-78096-044-9.