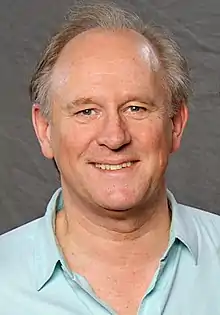

Brian Sinclair | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Brian Sinclair — circa 1985 | |

| Born | Wallace Brian Vaughan Sinclair 27 September 1915 Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 13 December 1988 (aged 73) Leeds, West Yorkshire, England |

| Resting place | Stonefall Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Royal School of Veterinary Studies, Edinburgh (1943: MRCVS) |

| Spouse |

Sheila Rose Seaton (m. 1944) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Donald Sinclair (brother) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | Veterinary Investigation Centre, Leeds |

| War service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Service years | 1944–46 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Corps | Royal Army Veterinary Corps |

| Conflict | World War II |

Wallace Brian Vaughan Sinclair MRCVS (27 September 1915 – 13 December 1988) was a British veterinary surgeon who worked for a time with his older brother Donald, and Donald's business partner, Alf Wight. Wight wrote a series of semi-autobiographical novels under the pen name James Herriot, with Sinclair and Donald appearing in fictional form as brothers Tristan and Siegfried Farnon. The novels were adapted in two films and television series under the name All Creatures Great and Small. Tristan was portrayed as a charming rogue who was still studying veterinary medicine in the early books, constantly having to re-take examinations because of his lack of application, often found in the pub, and provoking tirades from his bombastic elder brother Siegfried.

Sinclair studied veterinary medicine at the Royal Veterinary College in Edinburgh. He graduated in 1943 and returned to his brother's practice at 23 Kirkgate in Thirsk, Yorkshire. In the following year, he enlisted in the Royal Army Veterinary Corps and married Sheila Rose, the only daughter of Douglas Seaton, a general practitioner based in Leeds. Shortly after his marriage, he was posted to Haryana in India, and on demobilisation, he joined the Ministry of Agriculture's Sterility Advisory unit in Inverness, Scotland. In 1950, the ministry offered him a transfer to the Veterinary Investigation Centre in Weetwood Lane, Leeds, a diagnostic laboratory for veterinarians in Yorkshire.

Sinclair retired in 1977 after he had risen to become head of the investigation centre. In retirement, he gave talks on Herriot and Yorkshire, and spoke at veterinary schools in the United Kingdom and the United States. When Wight's first book was published, he was delighted to be captured as Tristan and remained enthusiastic about all Wight's books. He seemed to enjoy being a celebrity and would host informal evenings for tourist groups visiting "Herriot country". He was due to appear as the lead speaker at the annual meeting of the New York State Veterinary Medical Society but he died at Leeds General Infirmary before the meeting could take place.

Early life and education

Sinclair was born at Harrogate on 27 September 1915.[1] His father, James,[2] was the son of a crofter who had moved from the Isle of Sanday in the late 19th century.[3] James was said to have been a leather manufacturer but died when Sinclair was just two years old.[4]: 109 [3] Sinclair's elder sister, Elsa Vaughan,[5]: 297 married Cyril Walter Russell on 5 June 1934 at St Robert's Catholic Church, Harrogate, where he gave her away.[6] In the 1920s, his elder brother, Donald, was a veterinary student at the Royal School of Veterinary Studies in the University of Edinburgh.[3]

In his youth, Sinclair had considered a career in dentistry, but his interest turned to veterinary medicine after assisting his cousin, then a local veterinarian,[3] with bovine tuberculosis testing.[7] In 1932, he entered the veterinary school at Edinburgh but failed his undergraduate examinations. His brother transferred him to Glasgow Veterinary College but he was expelled after laughing in Professor John William Emslie's pathology class.[7][8][lower-alpha 1] He finally passed his professional examinations at Edinburgh in December 1943,[9] and in the same month, he was admitted a member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.[10] He worked for his brother while studying veterinary medicine, and after he graduated, he returned to his brother's practice at 23 Kirkgate in Thirsk, Yorkshire.[4]: 213

Veterinary career

After years of studying cattle, pigs, sheep and horses at Edinburgh University, I found myself in India in charge of 420 camels.

Sinclair, interview with Norman Harper, at Harrogate in October 1981.[11]

On 23 March 1944, Sinclair enlisted in the Royal Army Veterinary Corps (RAVC) and was given the rank of lieutenant.[12] He had been a member of the Edinburgh college Officers' Training Corps (OTC).[13]: 22 A month later, on 20 April 1944, he married Sheila Rose Seaton, the only daughter of Douglas Seaton, a general practitioner based in Leeds,[14]: 956 at St Robert's in Harrogate.[2] Four months after the wedding,[7] he was deployed to the Ambala district in the state of Haryana, India.[15]

Sinclair was put in charge of the mules and camels used by troops in Burma. At the end of the war, he joined India's dairy programme,[11] supervising the care of seventy thousand water buffalo on military farms, and teaching pregnancy testing to local veterinarians. The closest he got to military action was when a local tribe fired shots into the camp using home-made rifles.[7] Alf Wight would write long letters to Sinclair, often twenty pages,[7] that would give news from home and would finish with a description of the Yorkshire countryside. Sinclair would later say that "Reading the [Herriot] books I find that the descriptions of the countryside are just the same as in those old letters."[16]

Making the rank of captain, Sinclair was demobilised in 1946.[17] On his return to England, he visited the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) headquarters in Surrey in search of a job. He was offered a post at the ministry's Sterility Advisory unit at Church Street, Inverness, in the Scottish Highlands. He and his wife lived at 109 Culduthel Road, Inverness, and he travelled around Scotland advising farmers and crofters on livestock fertility. In 1950, the ministry offered him a transfer to the MAFF Veterinary Investigation Centre in Weetwood Lane, Leeds,[11] a diagnostic laboratory for veterinarians in Yorkshire.[7] He had enjoyed working and living in the Highlands, but decided to accept the transfer to his native Yorkshire, saying later, "I would never have accepted any transfer other than one to Yorkshire ... I loved the North and North-east that much."[11]

In 1953, Sinclair and Ken Sellers, a veterinary colleague at the centre,[18][lower-alpha 2] reported a cross-species infection of Salmonella typhimurium in shorthorn cows on a farm in Northumberland. The herd was milked in a shed that opened onto a duck house and a pigsty. The pigs, hens, and ducks were all found to be carrying Salmonella typhimurium, although none showed signs of infection. Sinclair and Sellers concluded that the poultry had caused the infection as they had only recently been introduced to the farm.[19]: 185–186 In 1959, he joined the joint MAFF Veterinary Laboratory Services and Public Health Laboratory Services committee on salmonellosis.[20]: 223–224 From 1965 until his retirement in 1977, he was the lead veterinary investigation officer for the centre.[7][lower-alpha 3]

From 1970 to 1974, Sinclair was the advisor to a veterinary clinical trial that attempted to eliminate scrapie from sheep by breeding out susceptibility to it. Scrapie can kill up to twenty-five percent of sheep in an infected flock and there is no known cure.[22] Six sheep farms, located in Yorkshire and Cumberland, were included in the trial. The farmers recorded the offspring of ewes and rams, and if they displayed symptoms of scrapie, then all affected sheep, including their relatives, would be culled from the flock.[23] The detailed recording and culling did have some success as at least one farm was able to declare itself free of scrapie by 1974.[22] Sinclair co-authored a number of papers on infections in cattle and sheep, such as Brucellosis and ringworm, but in general, he was not interested in academia. He considered that "having a sense of responsibility to the animal" is the most important value a veterinarian must have.[7]

Literary and dramatic portrayals

When Wight's first book was published, Sinclair was delighted to be captured as Tristan and remained enthusiastic about all Wight's books.[24] He had stated that the Herriot books and television shows were faithful to the truth, although occasionally, the truth was adapted for the purposes of the plot.[16] For example, in It Shouldn't Happen To a Vet there is an account of Sinclair letting a car run away and demolishing the local golf club hut. He read this and the next time he met Wight he said "'I don't remember doing that', and he said, 'You didn't it was me.' You see, it didn't fit James Herriot's image in the book, so he put it on to Tristan."[16]

In 2017, Alf Wight's son, Jim Wight, was interviewed and he discussed the James Herriot franchise. He made these comments about Sinclair:[25]

Brian [Sinclair] was accurately portrayed. A young man who was a delightful young fellow, but his whole aim in life was to work as little as possible and have as good a time as possible ... every time [Brian] failed his exams, which he did often when he was at veterinary school, Donald [Sinclair] had to pay and Donald didn't have money in those days ... So there was always that love-hate relationship between the two [brothers], very well portrayed in that first book.

The 1975 film All Creatures Great and Small was the first adaptation of Wight's semi-autobiographical novels of James Herriot. It was directed by Claude Whatham,[26]: 615 and starred Simon Ward and Anthony Hopkins as James Herriot and Siegfried Farnon, with Brian Stirner taking the part of Tristan.[5]: 294 At the time of filming, Stirner had played the lead role in Overlord, Stuart Cooper's 1975 film about the D-Day landings.[26]: 615 From the first film onwards, Wight gave a percentage of his income from film and television rights to Sinclair and his brother.[4]: 175 The sequel, It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet, premiered in 1976, but did not feature a Tristan character.[5]: 299

Encouraged by the cinematic success of the films, the BBC commissioned a television adaption of All Creatures Great and Small. Christopher Timothy starred as Herriot, Robert Hardy as Siegfried, and Peter Davison as Tristan.[27] After the first rehearsal, Davison met Sinclair, and stated that meeting him "was useful because I'd worried about how to make my Tristan endearing even though he behaved appallingly."[28]: 136 In return, Sinclair has said that he was "flattered that someone as tall and handsome as Peter Davison would play him on screen."[29][lower-alpha 4] The series premiered in 1978, and ended in 1980, when Herriot and Tristan were shown to leave Darrowby to join the war effort. A new series was commissioned in 1988, but Davison had other acting commitments, and was only able to make a few appearances as Tristan in that series.[27]

All Creatures Great and Small has been adapted for the stage by Simon Stallworthy. The play was first staged in 2010 at the Gala Theatre, Durham, with Jack Wharrier playing Tristan.[31] In 2014, a provincial tour of the play was produced by Bill Kenwright,[32] with Tristan being played by Lee Latchford-Evans.[33] Since 2020, a new television adaptation of All Creatures Great and Small has been produced by Playground Entertainment for Channel 5 in the United Kingdom, and PBS in the United States.[34] Callum Woodhouse played Tristan Farnon in the first three series, however, he is not expected to appear in series four as the Tristan character was called up to serve in the Royal Army Veterinary Corps in the series three Christmas special.[35]

Later life and death

In retirement, Sinclair joined an after-dinner speaking agency,[16][11] and was often invited to give speeches at farmers' functions in the north of England.[36] In 1979, he toured the United Kingdom giving talks to the Ladies' Circle and the Women's Institute,[37] on the subjects of Herriot and being a veterinary surgeon.[38] He was later paid to go on a cruise to speak on the same themes.[28]: 151 In addition to these talks, he would host informal evenings for American tourist groups visiting "Herriot country",[39] on tours organised by Earl Peel. The tours would include lunch at the Kings Arms Hotel, Askrigg, where much of the television series of All Creatures Great and Small was filmed.[40]

Later in 1979, Sinclair embarked on a lecture tour of veterinary schools in the United States.[41] On 7 November 1979, he spoke to the student chapter of the Iowa American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) at the C. Y. Stephens Auditorium. The audience numbered over a thousand and he was presented with a replica statue of "The Gentle Doctor" for his contribution to veterinary medicine.[7][lower-alpha 5] Later in the same month, he spoke at the twelfth conference of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners. To mark the occasion, the governor of Texas signed a proclamation declaring him an honorary citizen of the state. The mayor of San Antonio also issued a proclamation naming him honorary alcalde (mayor) of the city.[43]

Sinclair was interviewed on 21 October 1980 by Sue MacGregor when Woman's Hour broadcast from Harrogate.[44] However, he had begun to lose weight, and was admitted to St James's University Hospital, Leeds, for tests. His condition worsened until a new consultant was appointed to aid with a diagnosis. It was thought he was suffering from a rare pituitary gland disorder, and consequently, a range of drugs were prescribed. His condition improved but he had to remain on steroids for the rest of his life.[5]: 329–330 He had been suffering from circulatory problems for some time and a visit to Australia had to be cancelled.[16][5]: 344 He was also due to appear as the lead speaker at the centennial annual meeting of the New York State Veterinary Medical Society,[45] but he had a heart attack on 13 December 1988, and died at Leeds General Infirmary,[5]: 344 aged 73 years.[46]

A requiem was held on 19 December 1988 at St Robert's, Harrogate,[46] attended by Sinclair's brother and Wight.[5]: 344 Interment followed at Stonefall cemetery in Harrogate.[46] He and Wight had been life-long friends and had met almost every week in a bookshop at Harrogate.[5][lower-alpha 6] His death was an emotional blow to Wight and he would later say that "Brian [Sinclair] may have been a practical joker for most of his life ... but, beneath that hilarious veneer, was a sound and dependable man. A true friend in every sense of the word."[5]: 344 His wife remained friends with the Wights, meeting them at Harrogate each week for tea.[4]: 237 She died at Harrogate on 10 March 2001, aged 84 years, with her funeral also taking place at St Robert's on 16 March 2001.[48] They were survived by their three daughters, Anthea, Christine, and Diana.[46]

Selected publications

Academic papers

As author

- Sellers, Kenneth Charles; Sinclair, Wallace Brian Vaughan (1953). British Veterinary Association. "A case of Salmonella typhimurium infection in cattle and its isolation from other sources". Veterinary Record. London: John Wiley & Sons. 65: 233–234. ISSN 0042-4900. OCLC 803781252.

- Sellers, Kenneth Charles; Sinclair, Wallace Brian Vaughan; La Touche, Charles John (1956). British Veterinary Association. "Preliminary observations on natural and experimental ringworm in cattle". Veterinary Record. London: John Wiley & Sons. 68: 729–732. ISSN 0042-4900. OCLC 803781252.

- Hunter, D.; Sinclair, Wallace Brian Vaughan; Williams, David Rhys (March 1969). British Veterinary Association. "Infection of sheep in Yorkshire with Salmonella abortusovis". Veterinary Record. London: John Wiley & Sons. 84 (13): 350. ISSN 0042-4900. OCLC 803781252. PMID 5815883.

As experimental collaborator

- Crowley, James Patrick (October 1964). "Abortion and perinatal mortality in sheep associated with toxoplasmosis". Irish Journal of Agricultural Research. Castleknock: Teagasc. 3 (2): 159–164. ISSN 0578-7483. JSTOR 25555336.

Sinclair provided unpublished data on Brucella abortus.

- Wright, J. A.; Rook, John Allan Fynes; Panes, John Joseph (October 1969). "The winter decline in the solids‑not‑fat content of herd bulk‑milk supplies" (PDF). Journal of Dairy Research. Cambridge University Press. 36 (3): 399–407. doi:10.1017/S0022029900012917. ISSN 0022-0299. OCLC 1016374002. S2CID 86696150. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Pathology was taught in the fourth year of the course.[8]

- ↑ Kenneth Charles Sellers was later professor of veterinary pathology at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria.[18]

- ↑ In 1969, Sinclair's annual salary was around three thousand pounds (equivalent to thirty-eight thousand pounds in 2021).[21]

- ↑ Sinclair was a guest on Peter Davison's This Is Your Life episode that was broadcast on 25 March 1982 by ITV.[30]: 7

- ↑ The original statue by Christian Petersen stands at the entrance to the Hixson-Lied Small Animal Hospital, Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine.[42]

- ↑ Sinclair and Wight shared a common interest in Monty Python and the Marx Brothers.[47]: 513

References

- ↑ "Life and Times". www.jamesherriot.org. Brea. 9 March 2010. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- 1 2 "Marriages". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds. 22 April 1944. p. 4. ISSN 0963-1496. OCLC 18793101. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 "Obituary of Donald Sinclair". The Daily Telegraph. London. 17 July 1995. p. 21. ISSN 0841-7180. OCLC 1081089956. ProQuest 317497075.

- 1 2 3 4 Lord, Graham (1997). "14. The Rich Man in His Castle". James Herriot: The Life of a Country Vet (1st ed.). New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 1–276. ISBN 978-0-7867-0460-6. OCLC 1097594427. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wight, Jim (2000) [1999]. The Real James Herriot: A Memoir of My Father (1st American ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 1–371. ISBN 978-0-345-42151-7. OCLC 978715772. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ "Mr C. W. Russell and E. V. Sinclair". Yorkshire Evening Post. Leeds. 5 June 1934. p. 7. ISSN 0963-2255. OCLC 863719803. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Erdman, Lynn (January 1980). "Student-Faculty. Tristan Visits Iowa State College of Veterinary Medicine". Iowa State University Veterinarian. Ames: Iowa State University. 42 (1): 45–46. hdl:20.500.12876/47074. ISSN 0099-5851. OCLC 6267055. Article 13.

- 1 2 Lewis-Stempel, John (2012). "Part 2. The Art and the Science". Young Herriot: The Early Life and Times of James Herriot (Large print ed.). Bath: AudioGO. pp. 129, 138. ISBN 978-1-4458-8782-1. OCLC 1245991254. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ "Agriculture. New Veterinary Surgeons". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 23 December 1943. p. 8. ISSN 0307-5850. OCLC 624981792. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Register of Members". Register and Directory. London: Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons: 268. 1967. OCLC 220211397.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harper, Norman (14 October 1981). "Down North memory lane with 'Tristan Farnon'". Aberdeen Press and Journal. p. 12. ISSN 2632-1165. OCLC 271459455. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Royal Army Veterinary Corps". The London Gazette. No. 27797. 18 April 1944. p. 36478. OCLC 1013393168. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ Matthews, Peter K.; Macdonald, Alastair A.; Warwick, Colin M. (2015). "The Royal (Dick) Veterinary College Contingent of the Officers Training Corps (OTC)". Veterinary History. Staffordshire: Veterinary History Society. 18 (1): 5–27. hdl:1842/14176. ISSN 0301-6943. OCLC 642580690.

- ↑ Horner, Norman Gerald, ed. (6 May 1939). "Obituary". British Medical Journal. London: British Medical Association. 1 (4087): 953–956. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4087.953. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2209493. S2CID 220003954. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ "Royal Army Veterinary Corps. Lieutenants". Indian Army List. Part 2. New Delhi: Indian Defence Department: 2267A. September 1944. OCLC 46784577. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Derriman, Philip (4 July 1987). "The Real Tristan Farnon". The Sydney Morning Herald. pp. 180–182. ISSN 0312-6315. OCLC 226369741. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Ministry of Defence (August 1946). "Royal Army Veterinary Corps. Regular Army Emergency Commissions. Lieutenants". The Quarterly Army List. 2. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 2: 277. OCLC 1039944671. 2024e. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- 1 2 Boden, Edward (20 January 1993). "Obituary: Professor K. C. Sellers". The Independent. London. ISSN 0951-9467. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ↑ Hardy, Anne (2015) [2014]. "Part III Sites of Infection. Field and Farm". Salmonella Infections, Networks of Knowledge, and Public Health in Britain, 1880–1975. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 179–198. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198704973.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-870497-3. LCCN 2014940798. OCLC 903162166. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ↑

Public Health Laboratory Services; Veterinary Laboratory Services of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (June 1965). Fry, Rowdon Marrian (ed.). "Salmonellae in cattle and their feedingstuffs, and the relation to human infection". Journal of Hygiene. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 63 (2): 223–241. doi:10.1017/S0022172400045125. ISSN 0022-1724. PMC 2134652. PMID 14308353.

A report of the joint working party.

- ↑ Tatham, Francis Hugh Currer, ed. (1970). "Government and Public Offices. Veterinary Investigation Officers". Whitaker's Almanack. Vol. 102. London: J Whitaker & Sons. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-85021-029-3. OCLC 655394653. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- 1 2 "On‑farm Advice — The System in Action. Scrapie Problem Solved by Joint Effort". Veterinary Practice. Ewell: A. E. Morgan Publications. 7 (23): 2. December 1975. ISSN 0042-4897. OCLC 499792714. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ↑ "Breeding Out Scrapie". New Zealand Journal of Agriculture. Wellington: Department of Agriculture, Industries, and Commerce. 125 (2): 87. August 1972. ISSN 0028-8241. OCLC 220211397.

- ↑ "Who is James Herriot and How 'True' is All Creatures Great and Small?". www.thirteen.org. New York: Thirteen Media. 10 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ Van Maren, Jonathon (13 June 2017). "Remembering a bygone era: A conversation with James Herriot's son". thebridgehead.ca. Ontario: The Bridgehead. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- 1 2 Murphy, Robert, ed. (2006). Directors in British and Irish cinema: A Reference Companion (1st ed.). London: British Film Institute. pp. 570, 615. ISBN 978-1-84457-125-3. OCLC 69486111. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- 1 2 Evans, Jeff (2003) [2001]. "All Creatures Great and Small". The Penguin TV Companion (2nd ed.). London: Penguin. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-14-101221-6. OCLC 936505601. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- 1 2 Davison, Peter (2016). "7. My Arm Up a Cow". Is There Life Outside The Box?: An Actor Despairs. London: Kings Road Publishing. pp. 127–152. ISBN 978-1-78606-327-4. OCLC 1238058983. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ↑ Cabell, Craig (2013) [2011]. "6. Peter Davison". The Doctors Who's Who: Celebrating Its 50th Year. London: John Blake Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-78219-471-2. OCLC 1238058983. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy (January 1996). Brown, Anthony (ed.). "Peter Davison This is Your Life". In Vision. Doctor Who Season 19 Overview. The Making of a Television Drama Series. No. 62. Sandon: Jeremy Bentham. pp. 5–8. ISSN 0953-3303. OCLC 499409175. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ↑ Waugh, Ed (2 October 2010). "All Creatures Great and Small, Gala, Durham". The Northern Echo. Darlington. ISSN 2043-0442. OCLC 751105922. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ↑ "All Creatures Great and Small". www.uktw.co.uk. Boscastle: UK Theatre Web. 2022. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ↑ Owens, David (6 June 2014). "Box Office. Creature comforts". Western Mail. Cardiff. p. 2. OCLC 723659863. ProQuest 1532876277. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via WalesOnline.

- ↑ "Coming to MASTERPIECE: All Creatures Great and Small". www.pbs.org. Crystal City: PBS. 27 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ↑ Cormack, Morgan; Robinson, Abby (5 October 2023). "All Creatures Great and Small star explains impact of Tristan's absence". www.radiotimes.com. London: Immediate Media Company. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Amos, William (1987) [1985]. "Dramatis personae. Characters and their Counterparts, A to Z". The Originals : Who's Really Who in Fiction. London: Sphere Books. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7221-1069-0. OCLC 898833967. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ↑ "Circlers rally round Herriot's man". Rugeley Times. 17 March 1979. p. 6. OCLC 751640698. Retrieved 29 November 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Buckton, Janet (27 March 1979). "The real Tristan Farnon stands up". Coventry Evening Telegraph. p. 38. OCLC 232330580. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Andreae, Christopher (24 November 1981). "Herriot's Yorkshire". The Christian Science Monitor. Boston. ISSN 0882-7729. OCLC 137342671. ProQuest 1038831151. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via Christian Science Publishing Society.

- ↑ "For all tourists, great and small". The Orange County Register. Santa Ana. 3 March 1985. p. 284. ISSN 0886-4934. OCLC 12199155. Retrieved 28 November 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ↑ Porter, Becky (27 November 1979). "Sinclair discusses position in author's popular works". Daily O'Collegian. Vol. 85, no. 61. Stillwater. p. 1. OCLC 32593145. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via Oklahoma State University Library Electronic Publishing Center.

- ↑ "College Art". vetmed.iastate.edu. Ames: Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine. 2021. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑

Williams, Eric Idwal, ed. (April 1980). "Tristan Farnon Reflects" (PDF). Proceedings of the Annual Convention. Stillwater: American Association of Bovine Practitioners. 12: 11. ISSN 0524-1685. OCLC 263599151. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

San Antonio. 28 November to 1 December 1979.

- ↑ "Woman's Hour". Radio Times. Vol. 229, no. 2971. London: BBC. 18 April 1980. p. 55. ISSN 0961-8872. OCLC 265408915. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ↑ Lawton, Julie Anne, ed. (May 1989). "Letters". Veterinary News. New York: New York State Veterinary Medical Society. 53 (5): 191–202. hdl:2027/coo.31924056900289. ISSN 1045-3903. OCLC 15504793.

- 1 2 3 4 "Announcements and Personal". The Times. No. 63256. London. 15 December 1988. p. 19. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale IF0501752935.

- ↑

Chubb, David (March 1980). Ottinger, Ray (ed.). "Alias Tristan Farnon. An Interview with the Other Brother: Brian Sinclair". Veterinary Medicine & Small Animal Clinician. Bonner Springs: Veterinary Medicine Publishing Company. 75 (3): 512–514. ISSN 0042-4889. OCLC 1769070.

Otherwise known as VM/SAC. Article reprinted from the December 1979 issue of Intervet, the journal of the Student American Veterinary Medical Association.

- ↑ "Personal Column". The Times. No. 67085. London. 13 March 2001. p. 24. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale IF0502412703.

Further reading

- Herriot, James (2006) [First published in 1973]. "Chapter 8". It Shouldn't Happen To a Vet. London: Pan Books. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-0-3304-4346-3. OCLC 993228351. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Williams, Eric Idwal, ed. (January 1999). "12th World Association for Buiatrics Congress. Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 7 to 12 September 1982" (PDF). History of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners (AABP) 1964–1998. Stillwater: American Association of Bovine Practitioners. 1: 71–74. doi:10.21423/bovine-vol0no0p71-74. ISSN 0524-1685. OCLC 263599151. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

Includes photographs of the pre-convention tour to the Yorkshire Dales and Thirsk.

External links

- Official website of The World of James Herriot museum.