| Part of a series on |

| Anabaptism |

|---|

|

|

|

Anabaptists did not originate in England, but came from continental Europe to escape persecution from Switzerland. English Anabaptism did not touch the country as quickly as other countries since Henry VIII wanted to eradicate heresy quickly and wanted to push a unified religion in England.[1] In fact, during his rule in 1535, Henry VIII had them deported out of England officially with a proclamation that, "Ordered Anabaptists to leave the realm within twelve days after parliament adjourned or suffer the penalty of death."[2] In 1539 he pardoned Anabaptists with a similar proclamation to restore them to the Roman Catholic church. He wanted unity above all. While Henry VIII himself had broken away from the Catholic Church himself, Anabaptists did not face a welcoming country from the beginning of their coming to England. Both Henry and his Tudor successors have charged dissidents on the basis of Anabaptism, some of whom had not such convictions. Looking at primary sources, this means that just because they were charged as an Anabaptist does not mean they were one.

Definition

An Anabaptist believed that one should be baptized when a conscious decision had been made to become a follower and believer in Jesus Christ.[3] While the popular view that Anabaptism is an offshoot of Protestantism is not inherently false, it fared a very different treatment from the Protestant states at the time since their followers had dissenting beliefs from mainstream reformers.

Although many people tend to only think of Anabaptism as separatist and political, English Anabaptism was not separatist and did not baptize believers again, "Non-Separatist anabaptism in England took place not because of weakness in numbers or leadership, or because it was pietist in character, but because it was the most consistent and effective expression for that particular time and place."[4] They did not act out of radical beliefs since they were fewer in numbers and wanted to make a statement, but they wanted to be effective in their context.

During the late Tudor period (1530–1603) many English dissenting sects were lumped together under the term Anabaptism (even William Tyndale, the Bible translator, was charged with Anabaptist heresy), so it is hard to know about the groups of Anabaptists present in the British realms.[5]

English separatist congregations in exile on the Continent during 1580–90s probably provide a conduit for early English Anabaptist traditions. Separatist congregations such as Francis Johnson (1562–1618), and John Smyth (ca. 1554–1612) in Holland from 1593–1614 have often been cited as possible sources of Anabaptist influences into England. Thomas Helwys' congregation which had been associated with John Smyths' congregations in Holland returned to London about 1612. Helwys has been cited as the first English Baptist congregation on English soil.[6]

Background in England

The origins of anabaptism were Swiss, under Zwingli. Known for their rejection of infant baptism, they ended up being persecuted by both Protestants and Catholics alike.

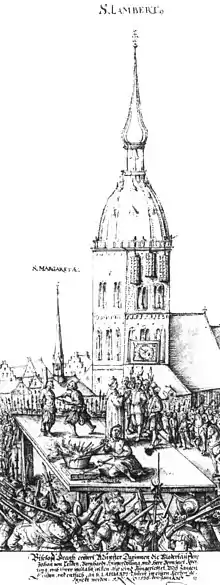

In the past, there have been two strains of Anabaptists movements that were propped up. The first was one involved a separation of the government. The government which was responsible for executions and war, went contrary to anabaptist beliefs. The second strain is what made the Anabaptists infamous in the public eye: the institution of an absolute Anabaptist theocracy via an uprooting of the government in power. One tragic example of the latter was the uprising at Münster. There were multiple people that were believed by the masses to be apostles. One of them Bockelson, who along with his father in law in law[7] would help instigate a takeover of the city hall, establishing their legal authority on the town that they believed to be the new Jerusalem. In establishing this religious government, private property was confiscated and authorized at will by the state, and had become a form of totalitarian proto-communism.

Those who belonged to the former strain of Anabaptism were persecuted because of this act of extremism. In an attempt to find a place free of religious persecution, Dutch and Flemish Anabaptists fled to England. However, they would be persecuted in England as well, as early as 1534.

Under the Tudors

Under the rule of Henry VIII, Anabaptists were persecuted as dissidents of the state. Since certain Anabaptists had been involved with Munster uprising, the word Anabaptist had become associated with violence and public disturbances. This combined with the Anabaptist beliefs on baptism (a radical belief at the time) caused Henry, under Cranmer's guidance chose to persecute them.[8] To Henry, it appeared to be in his best interest because he believed that such extremists were in a threat to the state. In response he enacted a few laws concerning anabaptists and "Between 1535-1546 large numbers of foreign Anabaptists were executed or burned at the stake for heresy. In 1535, some 25 Dutch Anabaptists who had fled the Amsterdam Uprisings were quickly rounded up. They were arrested, condemned for heresy and burned at the stake within the month."[9] In 1590 Anabaptists were ordered to leave England or join the Anglican Church (or the Strangers Church). The exile increased contact with Continental Anabaptists.

With Henry's death, Edward VI took charge of the English crown and religious policy. Having a more Protestant king did not quite ease the situation at all. Under Cranmer's guidance, Joan Bocher was executed for her Anabaptists beliefs. Even so, some of these concerns of preserving religious order were not unfounded. Thomas Putto, an Anabaptist, would disrupt religious services, causing concern for those above. Edward VI did grant a concession to the Anabaptists: he had the Stranger's church formed in 1550. Because the Stranger's Church was not placed directly under the Church of England, this move placed the Anabaptists outside the eye of the bishops. This not only reduced the executions but also helped support the English economy as there were anabaptists who were artisans.[10]

However, with Mary I in power, Anabaptists, along with other nonconformists were persecuted for their faith. Like their Protestant brethren, Anabaptists were judged for what people deemed as radical beliefs.[11] Given that Anabaptism had been used by people to describe Church radicals, it was not uncommon for mainstream Protestant victims to be tagged as Anabaptists as well. As a result, it is hard to distinguish during this time period who actually held Anabaptist convictions.

Upon Elizabeth's ascension to the throne, her primary concern was the preservation of order and the restoration of Protestantism within the state. The Anabaptists, who chose to object to her compromises and institutions were a threat to this. While the Anabaptists did return with the end of the Catholic regime, their hopes for better life were quickly dashed: the exile of anabaptists was put into effect in 1590. With the two other options being to submit to the Church of England or join the reestablished Stranger's church, most of the Anabaptists chose to leave.[12] When placing the Anabaptists under judgement of the law, such trials were done with the intent to challenge the anabaptist conscience.[13] Interrogation on the Anabaptist beliefs such as those on infant baptism and the divinity of Christ (in conjunction with Mary) were not out of question.

Following the death of Elizabeth, James I became the new ruler of England. He continued the policies of his predecessor that valued conformity under the state.[14] As Holland and England continued to maintain trade relations, it was of no surprise that Anabaptist ideas still made their way into England. Under his rule, the last public burning of heretics took place. Edward Wightman was the last to be burned publicly for heresy in England, and he was an Anabaptist. Although James I valued conformity for political reasons, this still shows the value he placed on making a public statement about religious minorities as well.

Location and geography

Due to persecution in Switzerland, many Anabaptists fled to England for safety. Anabaptists were scattered throughout England, even though they were only a minority.[15] "For I am afraid that Anabaptism is very ripe in England, though no perhaps in one entire body, but scattered in pieces".[16] Many settled in port cities and in London where they could maintain their religious beliefs to an extent.[17] Even though they were a minority religion, there were widespread Anabaptists beliefs throughout all of England since they had people to preach their teachings around London and let them spread. The Anabaptists were people of many types of classes. For instance, there were many cases like that such of Elizabeth Gaunt who was killed for her beliefs while only being a mere shopkeeper in London.

Persecution

Since Anabaptism did not ever had the advantage of being a state religion, it was a minority religion with a small following. Most people persecuted Anabaptists. John Foxe wrote about the persecution that Anabaptists faced such as "they are fined and imprisoned for refusing to take an oath; for not paying their tithes; for disturbing the public assemblies, and meeting in the streets, and places of public resort; some of them have been whipped for vagabonds, and for their plain speeches to the magistrate."[18] There was massive persecution during the 16th century against Anabaptists and other minority religious sects, and this continued on in to the 17th century until the present (albeit not as extreme). John Foxe did not necessarily agree with their theology but he did not want there to be extreme persecution for one's beliefs. For in 1660, Foxe's Book of Martyrs mentions a government proclamation that forbid the, "Anabaptists, Quakers, and Fifth Monarchy Men, to assemble or meet together under pretence of worshipping God, except it be in some parochial church, chapel, or in private houses, by consent of the persons there inhabiting, all meetings in other places being declared to be unlawful and riotous"[19] The monarchy viewed these groups in context of making public disruption not being legitimation places of worship. They did not validate the radical groups as legitimate but wanted them eradicated for less disruption in the public sphere. There were enactments to discourage Anabaptism, but the movement kept growing despite this persecution.

Prominent martyrs

Christopher Vitell

The first Anabaptist preacher in England was Christopher Vitell. He was an immigrant from the Netherlands who proclaimed Anabaptist teachings until he recanted under Queen Elizabeth.[20] He was known for sowing "religious revolt all over southern England".[21] He was also associated with the Family of Love, another radical religious minority that was often closely associated with Anabaptism. Many of his works were published between 1570 and 1575 and were widely circulated.[22] Elizabeth took care of the Familist sect quickly and burned their books and wanted people to recant. Even though he recanted his beliefs to avoid persecution, he was still a vital figure in proclaiming doctrine and teaching to the masses his beliefs.

Thomas Putto

One famous Anabaptist was Thomas Putto who would loudly proclaim Anabaptist sermons and promoter their literature and interrupt other religious services to do so. He was arrested and killed since he was an example of religious radicalism and insurrection. He was a tanner from Colechester, who on 5 May 1549, was executed "at St. Paul's Cross for denying that Christ descended into Hell".[23] Even though he had only dissented non-violently but it still caused apprehension among the officials. So, even when he was not explicitly causing violent actions, the officials still feared the Anabaptists because of his religion and reported lewd preaching.

Joan Bocher

A more well-known Anabaptist martyr is Joan Bocher of Kent. She was burnt at the stake in 1550 during the reign of King Edward VI Even though John Foxe tried to get the other famous Marian martyr John Rogers to save her from death, he agreed that burning was a crime "sufficiently mild for a crime as grave as heresy. For Joan, she lived in Steeple Bumpstead, which was known for its Lollard beliefs and had a long history of unorthodox belief and trouble with authorities resulting from those differences.[24] She had been accused of distributing the Tyndale New Testament and supposedly carried them under her skirts to sneak them into the royal court.[25] Even if this was a rumour, it shows the extent she was willing to get the Word of God out. Others perceptions of her were very negative, like Edumund Becke calling her, "the devil's eldest doughter" and "the wayward Virago," calling up negative stereotypes of womanhood to blacken her reputation.[26] She had interesting views about the incarnation and her Anabaptist beliefs were denied by both Protestants and Catholics.

Bartholomew Legate

While there were a number of Anabaptists executed after Joan Bocher, the next notable one is Bartholomew Legate. The Legate family were a well-known family in Essex. The Legate brothers were Walter, Thomas and Bartholomew and were known for their separatist opinions and Anabaptist beliefs, like arguing that Christ was not really God and rejecting the Church structure and doctrines such as the sacraments.[27] Bartholomew Legate is a famous martyr since he was one of the last heretics to be burned at the stake for religious heresy in England on 18 March 1611.[28] They were one of the last public executions since it scared commoners and they were ordered to death because of the problems they caused in the government. This execution was more of a casualty than merely being burned for their theological differences. The Anabaptists got in the way of the government more than getting in the way of the church, therefore James I dealt with people like Bartholomew Legate in this manner.

Edward Wightman

Edward Wightman was famously the last person to be burned publicly for heresy in England. He was not alone as a heretic, but was an Anabaptist who went against what James I wanted for his monarchy in terms of the religious vision he had. He wanted unity in religious belief and saw the Anabaptists as radical. The court pronounced a sentence against the "wicked heresies of the...Anabaptists".[29] When he was being burnt he recanted but then recanted his recantation and blasphemed audaciously. He was a central figure in his community and wanted to bring godly order and reformed orthodoxy to the countryside, he was not just a radical loner who wanted to stir up trouble with the government. Wightman shows a different side to the Anabaptists, so while they clearly had differing theological stances, they were not all just stirring up trouble.

Perception

The uprising by a radical strain of Anabaptists at Münster had left Europeans with a very negative view on Anabaptists. Their beliefs on baptism, private property, and the government made them an easy target for persecution.

During the English Reformation, and during the London Rebellions of 1548–1549, there was legislation against Anabaptists. While the Book of Common Prayer satisfied the general public, "authorities continued to be troubled by the more extreme Anabaptists. Although the Anabaptists were primarily a thorn in the side of the bishops, their role in urban disturbances at Deventer, Leyden, Amsterdam, and especially Munster made them highly suspect to the Mayor and Aldermen of London."[30] In response to impressions such as these, the Anabaptists were heavily persecuted both during and after the traditional period of the English Reformation. Public perception of them was mainly negative. Even under Zwingli from the Swiss, the Protestants persecuted the Anabaptists. They were persecuted for their theological differences because they were different from the dominant religions of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Bloody News from Dover

The pamphlet "Bloody Newes from Dover," from 1647, shows an Anabaptist woman holding the severed head of a child. The text says, "For, this bloody woman watching her opportunity, murdered the Boy, but was afterward apprehended, and suffered death."[31] Anti-Anabaptist propaganda shows how extreme people felt against this religious minority, and how there were pamphlets being sent around to make others afraid of how seemingly dangerous the Anabaptists were in their time.

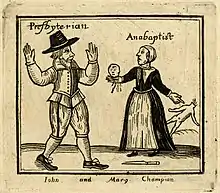

The Lecherous Anabaptist

Most times, people described Anabaptists in negative terms. For instance, this pamphlet is describing the "Lecherous Anabaptist".[32] This describes an account of an Anabaptist making inappropriate advances on a young Maid and exchanging a Bible for sexual favors, repeating the line, "For Frank twelve Geneva good Bibles did proffer, to lie with his Maid, but she slighted his offer." Stories like this were common, people took to a negative view of Anabaptists and tarnished their reputation with scathing literature and art work to bring down their reputations.

Relevance

The Anabaptists influenced other minority groups who sprung out of their movement, such as the Puritans or the Amish. Their beliefs in Baptism have become a main part of mainstream Baptism today. Even throughout the hundreds of years since their starting point, they are still in various cultural references today and a small religious movement across the world. Like in Voltaire's Candide, or as stock characters in Shakespeare's plays, they still play a part in English history and religious history.

It is generally assumed that the Baptist and other dissenting groups absorbed the British Anabaptists. The relations between Baptists and Anabaptists were early strained. In 1624 the then five existing Baptist churches of London issued an anathema against the Anabaptists.[33] Today there is little dialogue between Anabaptist organizations (such as the Mennonite World Conference) and the Baptist bodies. A student centre opened in 1953 has led to the establishment of nearly 20 congregations linked to an Anabaptist Network.[34]

Notes

- ↑ Joel Martin Gillaspie, Henry VIII: Supremacy, Religion, And The Anabaptists. (Utah State University, 2008)

- ↑ RUDOLPH WILLIAM HEINZE, TUDOR ROYAL PROCLAMATIONS: 1485-1553. The University of Iowa, 1965, 125.

- ↑ Gillaspie, Henry VIII.

- ↑ Walter Klaassen, "The Anabaptist Understanding of the Separation of the Church." Church History (1977), 421–36.

- ↑ "English Dissenters: Anabaptists". Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Wright, Stephen (2004), "Helwys, Thomas", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Rothbard, Murray N. "Messianic Communism in the Protestant Reformation." Messianic Communism in the Protestant Reformation, Mises Institute, 30 October 2017, mises.org/library/messianic-communism-protestant-reformation.

- ↑ Gillaspie, Henry VIII.

- ↑ QuelleNet. "ExLIBRIS: Home Page." Wayback Machine, ExLIBRIS

- ↑ QuelleNet, "ExLIBRIS"

- ↑ QuelleNet, "ExLIBRIS"

- ↑ QuelleNet, "ExLIBRIS"

- ↑ Alastair Duke, "MARTYRS WITH A DIFFERENCE: DUTCH ANABAPTIST VICTIMS OF ELIZABETHAN PERSECUTION." Nederlands Archief Voor Kerkgeschiedenis / Dutch Review of Church History 2000), 263-81.

- ↑ QuelleNet, "ExLIBRIS"

- ↑ EEBO, A short history of the Anabaptists of high and low Germany. 1647.

- ↑ EEBO, A short history of the Anabaptists of high and low Germany. 1647. 54

- ↑ "England - GAMEO."

- ↑ Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Accessed 18 February 2018.

- ↑ Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Accessed 18 February 2018.

- ↑ "Christopher Vitell." Wikipedia, 23 January 2018.

- ↑ Werner Stark, The Sociology of Religion: a Study of Christendom. Part 2: Sectarian Religion. (Routledge, 1998).

- ↑ Roger E. Moore, "The Spirit and the Letter: Marlowe's "Tamburlaine" and Elizabethan Religious Radicalism." Studies in Philology (2002), 123-51.

- ↑ B. L. Beer, "London and the Rebellions of 1548-1549." Journal of British Studies 12 (1972), 18.

- ↑ Mary E. Fissell, "The Politics of Reproduction in the English Reformation." Representations 87, no. 1 (2004), 61.

- ↑ Fissell, "Politics of Reproduction", 62.

- ↑ Fissell, "Politics of Reproduction", 62.

- ↑ Ian Atherton, The Burning of Edward Wightman: Puritanism, Prelacy and the Politics of Heresy in Early Modern England, (2005).

- ↑ Atherton, Burning of Edward Wightman.

- ↑ Atherton, Burning of Edward Wightman

- ↑ Beer, "London and the Rebellions of 1548-1549."

- ↑ Bloody newes from Dover. 1647. Thomason

- ↑ The Leacherous anabaptist, or, The dipper dipt Date:. Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery. (1681).

- ↑ Melton, J.G. Baptists in "Encyclopedia of American Religions". 1994

- ↑ "The Anabaptist Network". The Mennonite Trust. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

References

- Atherton, Ian. The Burning of Edward Wightman: Puritanism, Prelacy and the Politics of Heresy in Early Modern England, (2005).

- Beer, B. L. "London and the Rebellions of 1548-1549." Journal of British Studies 12, no. 1 (1972): 18.

- Bloody newes from Dover. 1647. Thomason

- Duke, Alastair. "MARTYRS WITH A DIFFERENCE: DUTCH ANABAPTIST VICTIMS OF ELIZABETHAN PERSECUTION." Nederlands Archief Voor Kerkgeschiedenis / Dutch Review of Church History 80, no. 3 (2000): 263–81.

- Fissell, Mary E. "The Politics of Reproduction in the English Reformation." Representations 87, no. 1 (2004): 61.

- Heinze, Rudolph William. 1965. "TUDOR ROYAL PROCLAMATIONS: 1485-1553." Order No. 6506689, The University of Iowa.

- Henry VIII: Supremacy, Religion, And The Anabaptists. Joel Martin Gillaspie Utah State University. 2008

- Klaassen, Walter. "The Anabaptist Understanding of the Separation of the Church." Church History 46, no. 4 (1977): 421–36.

- Moore, Roger E. "The Spirit and the Letter: Marlowe's "Tamburlaine" and Elizabethan Religious Radicalism." Studies in Philology 99, no. 2 (2002): 123-51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4174724.

- QuelleNet. “ExLIBRIS: Home Page.” Wayback Machine, ExLIBRIS

- Stark, Werner. The Sociology of Religion: a Study of Christendom. Part 2: Sectarian Religion. Routledge, 1998.

- “The Last Heretic, Twenty Minutes - BBC Radio 3.” BBC. Accessed February 27, 2018.

- The Leacherous anabaptist, or, The dipper dipt Date: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, (1681)