| History of Singapore |

|---|

|

|

|

Singapore in the Straits Settlements refers to a period in the history of Singapore between 1826 and 1942, during which Singapore was part of the Straits Settlements together with Penang and Malacca. Singapore was the capital and the seat of government of the Straits Settlement after it was moved from George Town in 1832.[1]

From 1830 to 1867, the Straits Settlements was a residency, or subdivision, of the Presidency of Bengal, in British India. In 1867, the Straits Settlements became a separate Crown colony, directly overseen by the Colonial Office in Whitehall in London. The period saw Singapore establish itself as an important trading port and developed into a major city with a rapid increase in population. The city remained as the capital and seat of government until British rule was suspended in February 1942, when the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Singapore during World War II.

Beginning of British rule in Singapore

In 1819, the British official, Stamford Raffles, landed in Singapore to establish a trading port. The island's status as a British outpost was initially in doubt, as the Dutch government soon issued bitter protests to the British government, arguing that their sphere of influence had been violated. The British government and the East India Company were initially worried about the potential liability of this new outpost, but that was soon overshadowed by Singapore's rapid growth as an important trading post. By 1822, it was made clear to the Dutch that the British had no intention of giving up the island.

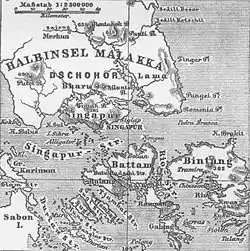

The status of Singapore as a British possession was cemented by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, which carved up the Malay archipelago between the two colonial powers. The area north of the Straits of Malacca, including Penang, Malacca and Singapore, was designated as the British sphere of influence, while the area south of the Straits was assigned to the Dutch.

This division had far-reaching consequences for the region: modern-day Malaysia and Singapore correspond to the British area established in the treaty, and modern-day Indonesia to the Dutch. In 1826, Singapore was grouped together with Penang and Malacca into a single administrative unit, the Straits Settlements, under the administration of the East India Company.

Residency of Bengal Presidency (1830–1867)

In 1830, the Straits Settlements became a residency, or subdivision, of the Presidency of Bengal, in British India.[2] This status continued until 1867.

Trade and economy

During the subsequent decades, Singapore grew to become one of the most important ports in the world. Several events during this period contributed to its success. British intervention in the Malay peninsula from the 1820s onwards culminated, during the 1870s, in the formation of British Malaya. During this period, Malaya became an increasingly important producer of natural rubber and tin, much of which was shipped out through Singapore.[3] Singapore also served as the administrative centre for Malaya until the 1880s, when the capital was shifted to Kuala Lumpur.

In 1834, the British government ended the East India Company's monopoly on the China trade, allowing other British companies to enter the market and leading to a surge in shipping traffic. The trade with China was opened with the signing of the Unequal Treaties, beginning in 1842. The advent of ocean-going steamships, which were faster and had a larger capacity than sailing ships, reduced transportation costs and led to a boom in trade. Singapore also benefited by acting as a coaling station for the Royal Navy and merchant ships. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 dramatically reduced the travel time from Europe to East Asia, again providing a boost for trade.

By 1880, over 1.5 million tons of goods were passing through Singapore each year, with around 80% of it transported by steamships and trading ships.[4] The main commercial activity was entrepôt trade which flourished under no taxation and little restriction. Many merchant houses were set up in Singapore mainly by European trading firms, but also by Jewish, Chinese, Arab, Armenian, American and Indian merchants. There were also many Chinese middlemen who handled most of the trade between the European and Asian merchants.[2]

Civil service

Despite Singapore's growing importance, the administration set up to govern the island was generally understaffed, poorly funded, weak, and ineffectual. Administrators were usually posted from India with little or no knowledge of the region, and were unfamiliar with local languages and customs of the people. As long as British trade was not affected, the administration was unconcerned with the welfare of the populace.

While Singapore's population had quadrupled between 1830 and 1867, the size of the civil service in Singapore had remained unchanged. In 1850 there were only twelve police officers to keep order in a city of nearly 60,000. Most people had no access to public health services, and diseases such as cholera and smallpox caused severe health problems, especially in overcrowded working-class areas. Malnutrition and opium-smoking were major social woes during this period.

Society

As early as 1827, the Chinese had become the largest ethnic group in Singapore. During the earliest years of the settlement, most of the Chinese in Singapore had been Peranakans, the descendants of Chinese who had settled in the archipelago centuries ago, who were usually well-to-do merchants. As the port developed, much larger numbers of Chinese coolies flocked to Singapore looking for work. These migrant workers were generally male, poor and uneducated, and had left China (mostly from southern China) to escape the political and economic disasters in their country.

They aspired to make their fortune in Southeast Asia and return home to China, but most were doomed to a life of low-paying unskilled labour. Until the 20th century, few Chinese ended up settling permanently, primarily because wives were in short supply. The sex ratio in Singapore's Chinese community was around hundred to one, mainly due to restrictions that the Chinese government imposed, up until the 1860s, on the migration of women.

Malays in Singapore were the second largest ethnic group in Singapore until the 1860s. Although many of the Malays continued to live in kampungs, or the traditional Malay villages, most worked as wage earners and craftsmen. This was in contrast to most Malays in Malaya, who remained farmers.

By 1860, Indians became the second largest ethnic group. They consisted of unskilled labourers like the Chinese coolies, traders, soldiers garrisoned at Singapore by the government in Calcutta,[2] as well as a number of Indian convicts who were sent to Singapore to carry out public works projects, such as clearing jungles and swampy marshes and laying out roads. They also helped construct many buildings, including St. Andrew's Cathedral, and many Hindu temples. After serving their sentences, many convicts chose to stay in Singapore.

As a result of the administration's hands-off attitude and the predominantly male, transient, and uneducated nature of the population, the society of Singapore was rather lawless and chaotic. Prostitution, gambling, and drug abuse (particularly of opium) were widespread. Chinese criminal secret societies (analogous to modern-day triads) were extremely powerful; some had tens of thousands of members, and turf wars between rival societies occasionally led to death tolls numbering in the hundreds. Attempts to suppress these secret societies had limited success, and they continued to be a problem well into the 20th century.[5]

The colonial division of the architecture of Singapore developed in this period, recognisable elements which remain today in the form of shophouses, such as those found in Little India or Chinatown.

Crown colony (1867–1942)

.jpg.webp)

As Singapore continued to grow, the deficiencies in the Straits Settlements administration became increasingly apparent. Apart from the indifference of British India's administrators to local conditions, there was immense bureaucracy and red tape which made it difficult to pass new laws. Singapore's merchant community began agitating against British Indian rule, in favour of establishing Singapore as a separate colony of Britain. The British government finally agreed to make the Straits Settlements a Crown colony on 1 April 1867, receiving orders directly from the Colonial Office rather than from India.

As a Crown Colony, the Straits Settlements was ruled by a governor, based in Singapore, with the assistance of executive and legislative councils. Although the councils were not elected, more representatives for the local population were gradually included over the years.

Chinese protectorate

The colonial government embarked on several measures to address the serious social problems facing Singapore. For example, a Chinese Protectorate under Pickering was established in 1877 to address the needs of the Chinese community, including controlling the worst abuses of the coolie trade and protecting Chinese women from forced prostitution. In 1889 Governor Sir Cecil Clementi Smith banned secret societies in colonial Singapore, driving them underground. Nevertheless, many social problems persisted up through the post-war era, including an acute housing shortage and generally poor health and living standards.

Tongmenghui

In 1906, the Tongmenghui, a revolutionary Chinese organisation dedicated to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty led by Sun Yat-Sen, founded its Nanyang branch in Singapore, which was to serve as the organisation's headquarters in Southeast Asia. The Tongmenghui would eventually be part of several groups that took part in the Xinhai Revolution and established the Republic of China. Overseas Chinese like the immigrant Chinese population in Singapore donated generously to groups like the Tongmenghui, which would eventually evolve into the Kuomintang. Today, this founding is commemorated in the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall - previously known as Sun Yat Sen Villa or Wang Qing Yuan (meaning "House of the Heavens above" in Chinese) - in Singapore where the branch operated from. According to George Yeo, the Foreign Minister of Singapore, in those days the Kuomintang party flag, which later became the flag of the Republic of China, was sewn in the Sun Yat Sen Villa by Teo Eng Hock and his wife.[6][7]

1915 Singapore Mutiny

Singapore was not directly affected by the First World War (1914–18), as the conflict did not spread to Southeast Asia. The most significant event during the war was a mutiny in 1915 by sepoys of the 5th Light Infantry from British India who were garrisoned in Singapore. On the day before the regiment was due to depart for Hong Kong, and hearing rumours that they were to be sent to fight the Ottoman Empire,[8] about half of the Indian soldiers mutinied. They killed several of their officers and some civilians before the mutiny was suppressed by British Empire and allied forces plus local troops from Johore.[9]

Singapore in the 1920s and 1930s

This is how Lee Kuan Yew, its Prime Minister for 32 years, described Singapore:

- I grew up in a Singapore of the 1920s and 1930s. The population was less than a million and most of Singapore was covered by mangrove swamps, rubber plantations, and secondary forest because rubber had failed, and forests around Mandai/Bukit Timah took its place.[10]

In these early decades, the island was riddled with opium houses and prostitution, and came to be widely monikered as "Sin-galore"[11]

Naval base

After the First World War, the British government devoted significant resources to building a naval base in Singapore, as a deterrent to the increasingly ambitious Japanese Empire. Originally announced in 1923, the construction of the base proceeded slowly until the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

When completed in 1939, at the very large cost of $500 million, the base boasted what was then the largest dry dock in the world, the third-largest floating dock, and having enough fuel tanks to support the entire British navy for six months. It was defended by heavy 15-inch naval guns stationed at Fort Siloso, Fort Canning and Labrador, as well as a Royal Air Force airfield at Tengah Air Base. Winston Churchill touted it as the "Gibraltar of the East" and military discussions often referred to the base as simply "East of Suez"

The base did not have a fleet. The British Home Fleet was stationed in Europe, and the British could not afford to build a second fleet to protect its interests in Asia. The so-called Singapore strategy called for the Home Fleet to sail quickly to Singapore in the event of an emergency. However, after World War II broke out in 1939, the fleet was fully occupied with defending Britain, and only the small Force Z was sent to defend the colony.

People in Singapore who held German identify papers, including Jews fleeing the Nazis such as Karl Duldig, Slawa Duldig, and Eva Duldig, were arrested and deported from Singapore.[12][13] The British colonial government classified them as "citizens of an enemy country".[14][15][13][16]

See also

References

| Library resources about Singapore in the Straits Settlements |

- ↑ Turnbull, C. M. (1972) The Straits Settlements, 1826–1867: Indian Presidency to Crown Colony, Athlone Press, London. P3

- 1 2 3 "Singapore - A Flourishing Free Ports". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ↑ "The Straits Settlements". Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ↑ George P. Landow. "Singapore Harbor from Its Founding to the Present: A Brief Chronology". Archived from the original on 12 August 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ↑ Lim, Irene. (1999) Secret societies in Singapore, National Heritage Board, Singapore History Museum, Singapore ISBN 981-3018-79-8

- ↑ The Straits Times (printed edition), July 17, 2010, page A17, 'This is common ancestry' by Rachel Chang

- ↑ Dr Sun & 1911 Revolution: Teo Eng Hock (1871 - 1957) Archived 26 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Philip Mason, pages 426–427 "A Matter of Honour", ISBN 0-333-41837-9

- ↑ Harper, R.W.E.; Miller, Harry (1984). Singapore Mutiny. Oxford University Press. pp. 175–179. ISBN 978-0-19-582549-7.

- ↑ Sunday Times (printed edition), 25 July 2010, page 9, "Living with Nature" (an email interview with Lee Kuan Yew) by Lim Yann Ling

- ↑ IT Figures S4 - Toggle, 28 December 2015

- ↑ Elder, John (20 August 2011). "Faces from the past return to their rightful home at last". The Age.

- 1 2 "To the other side of the world," National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism.

- ↑ Phil Mercer (29 April 2022). "Australian Musical Charts Family's Escape from Nazis in Europe". Voice of America.

- ↑ Henry Benjamin (4 March 2013). "Times at Tatura". J-Wire.

- ↑ Yeo Mang Thong (2019). Migration, Transmission, Localisation; Visual Art in Singapore (1866-1945), National Gallery Singapore.

Further reading

- Firaci, Biagio (10 June 2014). "Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles and the British Colonization of Singapore among Penang, Melaka and Bencoonen".