| Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sudden acute respiratory syndrome[1] |

| |

| Electron micrograph of SARS coronavirus virion | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, persistent dry cough, headache, muscle pains, difficulty breathing |

| Complications | Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with other comorbidities that eventually leads to death |

| Duration | 2002–2004 |

| Causes | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) |

| Prevention | Hand washing, cough etiquette, avoiding close contact with infected persons, avoiding travel to affected areas[2] |

| Prognosis | 9.5% chance of death (all countries) |

| Frequency | 8,096 cases total |

| Deaths | 783 known |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1, the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus.[3] The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the syndrome caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak. In the 2010s, Chinese scientists traced the virus through the intermediary of Asian palm civets to cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township, Yunnan.[4]

SARS was a relatively rare disease; at the end of the epidemic in June 2003, the incidence was 8,469 cases with a case fatality rate (CFR) of 11%.[5] No cases of SARS-CoV-1 have been reported worldwide since 2004.[6]

In December 2019, another strain of SARS-CoV was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).[7] This strain, which is related to SARS-CoV-1, caused coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a disease that brought about the COVID-19 pandemic.[8]

Signs and symptoms

SARS produces flu-like symptoms which may include fever, muscle pain, lethargy, cough, sore throat, and other nonspecific symptoms. The only symptom common to all patients appears to be a fever above 38 °C (100 °F). SARS often leads to shortness of breath and pneumonia, which may be direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia.[9]

The average incubation period for SARS is 4–6 days, although it is rarely as short as 1 day or as long as 14 days.[10]

Transmission

The primary route of transmission for SARS-CoV is contact of the mucous membranes with respiratory droplets or fomites. While diarrhea is common in people with SARS, the fecal–oral route does not appear to be a common mode of transmission.[10] The basic reproduction number of SARS-CoV, R0, ranges from 2 to 4 depending on different analyses. Control measures introduced in April 2003 reduced the R to 0.4.[10]

Diagnosis

SARS-CoV may be suspected in a patient who has:

- Any of the symptoms, including a fever of 38 °C (100 °F) or higher, and

- Either a history of:

- Contact (sexual or casual) with someone with a diagnosis of SARS within the last 10 days or

- Travel to any of the regions identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as areas with recent local transmission of SARS.

- Clinical criteria of Sars-CoV diagnosis[11]

- Early illness: equal to or more than 2 of the following: chills, rigors, myalgia, diarrhea, sore throat (self-reported or observed)

- Mild-to-moderate illness: temperature of >38 °C (100 °F) plus indications of lower respiratory tract infection (cough, dyspnea)

- Severe illness: ≥1 of radiographic evidence, presence of ARDS, autopsy findings in late patients.

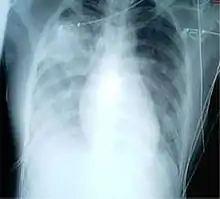

For a case to be considered probable, a chest X-ray must be indicative for atypical pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The WHO has added the category of "laboratory confirmed SARS" which means patients who would otherwise be considered "probable" and have tested positive for SARS based on one of the approved tests (ELISA, immunofluorescence or PCR) but whose chest X-ray findings do not show SARS-CoV infection (e.g. ground glass opacities, patchy consolidations unilateral).[11][12]

The appearance of SARS-CoV in chest X-rays is not always uniform but generally appears as an abnormality with patchy infiltrates.[13]

Prevention

There is a vaccine for SARS, although in March 2020 immunologist Anthony Fauci said the CDC developed one and placed it in the Strategic National Stockpile.[14] That vaccine, is a final product and field-ready as of March 2022.[15] Clinical isolation and vaccination remain the most effective means to prevent the spread of SARS. Other preventive measures include:

- Hand-washing with soap and water, or use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer[16]

- Disinfection of surfaces of fomites to remove viruses

- Avoiding contact with bodily fluids

- Washing the personal items of someone with SARS in hot, soapy water (eating utensils, dishes, bedding, etc.)[17]

- Avoiding travel to affected areas

- Wearing masks and gloves[18]

- Keeping people with symptoms home from school

- Simple hygiene measures

- Distancing oneself at least 6 feet if possible to minimize the chances of transmission of the virus

Many public health interventions were made to try to control the spread of the disease, which is mainly spread through respiratory droplets in the air, either inhaled or deposited on surfaces and subsequently transferred to a body's mucous membranes. These interventions included earlier detection of the disease; isolation of people who are infected; droplet and contact precautions; and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), including masks and isolation gowns.[5] A 2017 meta-analysis found that for medical professionals wearing N-95 masks could reduce the chances of getting sick up to 80% compared to no mask.[19] A screening process was also put in place at airports to monitor air travel to and from affected countries.[20]

SARS-CoV is most infectious in severely ill patients, which usually occurs during the second week of illness. This delayed infectious period meant that quarantine was highly effective; people who were isolated before day five of their illness rarely transmitted the disease to others.[10]

As of 2017, the CDC was still working to make federal and local rapid-response guidelines and recommendations in the event of a reappearance of the virus.[21]

Treatment

As SARS is a viral disease, antibiotics do not have direct effect but may be used against bacterial secondary infection. Treatment of SARS is mainly supportive with antipyretics, supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation as needed. While ribavirin is commonly used to treat SARS, there seems to have little to no effect on SARS-CoV, and no impact on patient's outcomes.[22] There is currently no proven antiviral therapy. Tested substances, include ribavirin, lopinavir, ritonavir, type I interferon, that have thus far shown no conclusive contribution to the disease's course.[23] Administration of corticosteroids, is recommended by the British Thoracic Society/British Infection Society/Health Protection Agency in patients with severe disease and O2 saturation of <90%.[24]

People with SARS-CoV must be isolated, preferably in negative-pressure rooms, with complete barrier nursing precautions taken for any necessary contact with these patients, to limit the chances of medical personnel becoming infected.[11] In certain cases, natural ventilation by opening doors and windows is documented to help decreasing indoor concentration of virus particles.[25]

Some of the more serious damage caused by SARS may be due to the body's own immune system reacting in what is known as cytokine storm.[26]

Vaccine

Vaccines can help immune system to create enough antibodies and also it can help to decrease a risk of side effects like arm pain, fever, headache etc.[27][28] According to research papers published in 2005 and 2006, the identification and development of novel vaccines and medicines to treat SARS was a priority for governments and public health agencies around the world.[29][30][31] In early 2004, an early clinical trial on volunteers was planned.[32] A major researcher's 2016 request, however, demonstrated that no field-ready SARS vaccine had been completed because likely market-driven priorities had ended funding.[15]

Prognosis

Several consequent reports from China on some recovered SARS patients showed severe long-time sequelae. The most typical diseases include, among other things, pulmonary fibrosis, osteoporosis, and femoral necrosis, which have led in some cases to the complete loss of working ability or even self-care ability of people who have recovered from SARS. As a result of quarantine procedures, some of the post-SARS patients have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder.[33][34]

Epidemiology

SARS was a relatively rare disease; at the end of the epidemic in June 2003, the incidence was 8,422 cases with a case fatality rate (CFR) of 11%.[5]

The case fatality rate (CFR) ranges from 0% to 50% depending on the age group of the patient.[10] Patients under 24 were least likely to die (less than 1%); those 65 and older were most likely to die (over 55%).[35]

As with MERS and COVID-19, SARS resulted in significantly more deaths of males than females.

| Country or region | Cases | Deaths | Fatality (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,327 | 349 | 6.6 | ||

| 1,755 | 299 | 17.0 | ||

| 346 | 81 | 23.4[37] | ||

| 251 | 43 | 17.1 | ||

| 238 | 33 | 13.9 | ||

| 63 | 5 | 7.9 | ||

| 27 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 14 | 2 | 14.3 | ||

| 9 | 2 | 22.2 | ||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7 | 1 | 14.3 | ||

| 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 40.0 | ||

| 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 100.0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total excluding China[lower-alpha 1] | 2,769 | 454 | 16.4 | |

| Total (29 territories) | 8,096 | 782 | 9.6 | |

Outbreak in South China

The SARS epidemic began in the Guangdong province of China in November 2002. The earliest case developed symptoms on 16 November 2002.[38] The index patient, a farmer from Shunde, Foshan, Guangdong, was treated in the First People's Hospital of Foshan. The patient died soon after, and no definite diagnosis was made on his cause of death. Despite taking some action to control it, Chinese government officials did not inform the World Health Organization of the outbreak until February 2003. This lack of openness caused delays in efforts to control the epidemic, resulting in criticism of the People's Republic of China from the international community. China officially apologized for early slowness in dealing with the SARS epidemic.[39]

The viral outbreak was subsequently genetically traced to a colony of cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township, Yunnan.[4]

The outbreak first came to the attention of the international medical community on 27 November 2002, when Canada's Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), an electronic warning system that is part of the World Health Organization's Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), picked up reports of a "flu outbreak" in China through Internet media monitoring and analysis and sent them to the WHO. While GPHIN's capability had recently been upgraded to enable Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish translation, the system was limited to English or French in presenting this information. Thus, while the first reports of an unusual outbreak were in Chinese, an English report was not generated until 21 January 2003.[40][41] The first super-spreader was admitted to the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital in Guangzhou on 31 January, which soon spread the disease to nearby hospitals.[42]

In early April 2003, after a prominent physician, Jiang Yanyong, pushed to report the danger to China,[43][44] there appeared to be a change in official policy when SARS began to receive a much greater prominence in the official media. Some have directly attributed this to the death of an American teacher, James Earl Salisbury, in Hong Kong.[45] It was around this same time that Jiang Yanyong made accusations regarding the undercounting of cases in Beijing military hospitals.[43][44] After intense pressure, Chinese officials allowed international officials to investigate the situation there. This revealed problems plaguing the aging mainland Chinese healthcare system, including increasing decentralization, red tape, and inadequate communication.[46]

Many healthcare workers in the affected nations risked their lives and died by treating patients, and trying to contain the infection before ways to prevent infection were known.[47]

Spread to other regions

The epidemic reached the public spotlight in February 2003, when an American businessman traveling from China, Johnny Chen, became affected by pneumonia-like symptoms while on a flight to Singapore. The plane stopped in Hanoi, Vietnam, where the patient died in Hanoi French Hospital. Several of the medical staff who treated him soon developed the same disease despite basic hospital procedures. Italian doctor Carlo Urbani identified the threat and communicated it to WHO and the Vietnamese government; he later died from the disease.[48]

The severity of the symptoms and the infection among hospital staff alarmed global health authorities, who were fearful of another emergent pneumonia epidemic. On 12 March 2003, the WHO issued a global alert, followed by a health alert by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Local transmission of SARS took place in Toronto, Ottawa, San Francisco, Ulaanbaatar, Manila, Singapore, Taiwan, Hanoi and Hong Kong whereas within China it spread to Guangdong, Jilin, Hebei, Hubei, Shaanxi, Jiangsu, Shanxi, Tianjin, and Inner Mongolia.

Hong Kong

The disease spread in Hong Kong from Liu Jianlun, a Guangdong doctor who was treating patients at Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital.[49] He arrived in February and stayed on the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel in Kowloon, infecting 16 of the hotel visitors. Those visitors traveled to Canada, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam, spreading SARS to those locations.[50]

Another larger cluster of cases in Hong Kong centred on the Amoy Gardens housing estate. Its spread is suspected to have been facilitated by defects in its bathroom drainage system that allowed sewer gases including virus particles to vent into the room. Bathroom fans exhausted the gases and wind carried the contagion to adjacent downwind complexes. Concerned citizens in Hong Kong worried that information was not reaching people quickly enough and created a website called sosick.org, which eventually forced the Hong Kong government to provide information related to SARS in a timely manner.[51] The first cohort of affected people were discharged from hospital on 29 March 2003.[52]

Canada

The first case of SARS in Toronto was identified on 23 February 2003.[53] Beginning with an elderly woman, Kwan Sui-Chu, who had returned from a trip to Hong Kong and died on 5 March, the virus eventually infected 257 individuals in the province of Ontario. The trajectory of this outbreak is typically divided into two phases, the first centring around her son Tse Chi Kwai, who infected other patients at the Scarborough Grace Hospital and died on 13 March. The second major wave of cases was clustered around accidental exposure among patients, visitors, and staff within the North York General Hospital. The WHO officially removed Toronto from its list of infected areas by the end of June 2003.[54]

The official response by the Ontario provincial government and Canadian federal government has been widely criticized in the years following the outbreak. Brian Schwartz, vice-chair of Ontario's SARS Scientific Advisory Committee, described public health officials' preparedness and emergency response at the time of the outbreak as "very, very basic and minimal at best".[55] Critics of the response often cite poorly outlined and enforced protocol for protecting healthcare workers and identifying infected patients as a major contributing factor to the continued spread of the virus. The atmosphere of fear and uncertainty surrounding the outbreak resulted in staffing issues in area hospitals when healthcare workers elected to resign rather than risk exposure to SARS.

Identification of virus

In late February 2003, Italian doctor Carlo Urbani was called into The French Hospital of Hanoi to look at Johnny Chen, an American businessman who had fallen ill with what doctors thought was a bad case of influenza. Urbani realized that Chen's ailment was probably a new and highly contagious disease. He immediately notified the WHO. He also persuaded the Vietnamese Health Ministry to begin isolating patients and screening travelers, thus slowing the early pace of the epidemic.[56] He subsequently contracted the disease himself, and died in March 2003.[57][58]

Malik Peiris and his colleagues became the first to isolate the virus that causes SARS,[59] a novel coronavirus now known as SARS-CoV-1.[60][61] By June 2003, Peiris, together with his long-time collaborators Leo Poon and Guan Yi, has developed a rapid diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-1 using real-time polymerase chain reaction.[62] The CDC and Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory identified the SARS genome in April 2003.[63][64] Scientists at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands demonstrated that the SARS coronavirus fulfilled Koch's postulates thereby suggesting it as the causative agent. In the experiments, macaques infected with the virus developed the same symptoms as human SARS patients.[65]

Origin and animal vectors

In late May 2003, a study was conducted using samples of wild animals sold as food in the local market in Guangdong, China.[66] The study found that "SARS-like" coronaviruses could be isolated from masked palm civets (Paguma sp.). Genomic sequencing determined that these animal viruses were very similar to human SARS viruses, however they were phylogenetically distinct, and so the study concluded that it was unclear whether they were the natural reservoir in the wild. Still, more than 10,000 masked palm civets were killed in Guangdong Province since they were a "potential infectious source."[67] The virus was also later found in raccoon dogs (Nyctereuteus sp.), ferret badgers (Melogale spp.), and domestic cats.

In 2005, two studies identified a number of SARS-like coronaviruses in Chinese bats.[68][69] Phylogenetic analysis of these viruses indicated a high probability that SARS coronavirus originated in bats and spread to humans either directly or through animals held in Chinese markets. The bats did not show any visible signs of disease, but are the likely natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. In late 2006, scientists from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention of Hong Kong University and the Guangzhou Centre for Disease Control and Prevention established a genetic link between the SARS coronavirus appearing in civets and in the second, 2004 human outbreak, bearing out claims that the disease had jumped across species.[70]

It took 14 years to find the original bat population likely responsible for the SARS pandemic.[71] In December 2017, "after years of searching across China, where the disease first emerged, researchers reported ... that they had found a remote cave in Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township, Yunnan province, which is home to horseshoe bats that carry a strain of a particular virus known as a coronavirus. This strain has all the genetic building blocks of the type that triggered the global outbreak of SARS in 2002."[4] The research was performed by Shi Zhengli, Cui Jie, and co-workers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, China, and published in PLOS Pathogens. The authors are quoted as stating that "another deadly outbreak of SARS could emerge at any time. The cave where they discovered their strain is only a kilometre from the nearest village."[4][72] The virus was ephemeral and seasonal in bats.[73] In 2019, a similar virus to SARS caused a cluster of infections in Wuhan, eventually leading to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A small number of cats and dogs tested positive for the virus during the outbreak. However, these animals did not transmit the virus to other animals of the same species or to humans.[74][75]

Containment

The World Health Organization declared severe acute respiratory syndrome contained on 5 July 2003. The containment was achieved through successful public health measures.[76] In the following months, four SARS cases were reported in China between December 2003 and January 2004.[77][78]

While SARS-CoV-1 probably persists as a potential zoonotic threat in its original animal reservoir, human-to-human transmission of this virus may be considered eradicated because no human case has been documented since four minor, brief, subsequent outbreaks in 2004.[76]

Laboratory accidents

After containment, there were four laboratory accidents that resulted in infections.

- One postdoctoral student at the National University of Singapore in Singapore in August 2003[79]

- A 44-year-old senior scientist at the National Defense University in Taipei in December 2003. He was confirmed to have the SARS virus after working on a SARS study in Taiwan's only BSL-4 lab. The Taiwan CDC later stated the infection occurred due to laboratory misconduct.[80][81]

- Two researchers at the Chinese Institute of Virology in Beijing, China around April 2004, who spread it to around six other people. The two researchers contracted it 2 weeks apart.[82]

Study of live SARS specimens requires a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) facility; some studies of inactivated SARS specimens can be done at biosafety level 2 facilities.[83]

Society and culture

Fear of contracting the virus from consuming infected wild animals resulted in public bans and reduced business for meat markets in southern China and Hong Kong.[84]

See also

- 2009 swine flu pandemic

- Aerosol

- Avian influenza

- Bat-borne virus

- Coronavirus disease 2019 – a disease caused by Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- Health crisis

- Health in China

- Healthy building

- Indoor air quality

- List of medical professionals who died during the SARS outbreak

- Middle East respiratory syndrome – a coronavirus discovered in June 2012 in Saudi Arabia

- SARS conspiracy theory

- Sick building syndrome

- Zhong Nanshan

References

- ↑ Likhacheva A (April 2006). "SARS Revisited". The Virtual Mentor. 8 (4): 219–22. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.4.jdsc1-0604. PMID 23241619. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

SARS—the acronym for sudden acute respiratory syndrome

- ↑ "SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) – NHS". National Health Service. 24 October 2019. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ↑ Al-Juhaishi, Atheer Majid Rashid; Aziz, Noor D. (12 September 2022). "Safety and Efficacy of antiviral drugs against covid-19 infection: an updated systemic review". Medical and Pharmaceutical Journal. 1 (2): 45–55. doi:10.55940/medphar20226. ISSN 2957-6067. S2CID 252960321. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 The locality was referred to be "a cave in Kunming" in earlier sources because the Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township is administratively part of Kunming, though 70 km apart. Xiyang was identified on Wang N, Li SY, Yang XL, Huang HM, Zhang YJ, Guo H, et al. (February 2018). "Serological Evidence of Bat SARS-Related Coronavirus Infection in Humans, China" (PDF). Virologica Sinica. 33 (1): 104–107. doi:10.1007/s12250-018-0012-7. PMC 6178078. PMID 29500691. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- For an earlier interview of the researchers about the locality of the caves, see: 吴跃伟 (8 December 2017). "专访"病毒猎人":在昆明一蝙蝠洞发现SARS病毒所有基因". 澎湃新闻. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 Chan-Yeung M, Xu RH (November 2003). "SARS: epidemiology". Respirology. 8 (s1): S9-14. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00518.x. PMC 7169193. PMID 15018127.

- ↑ "SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)". NHS Choices. UK National Health Service. 3 October 2014. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

Since 2004, there haven't been any known cases of SARS reported anywhere in the world.

- ↑ "New coronavirus stable for hours on surfaces". National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH.gov. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Myth busters". WHO.int. World Health Organization. 2019. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ Peiris JS, Chu CM, Cheng VC, Chan KS, Hung IF, Poon LL, et al. (May 2003). "Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study". Lancet. 361 (9371): 1767–1772. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13412-5. PMC 7112410. PMID 12781535.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). World Health Organization. 2003. hdl:10665/70863.

- 1 2 3 "SARS | Home | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome | SARS-CoV Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 October 2019. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ↑ Chan PK, To WK, Ng KC, Lam RK, Ng TK, Chan RC, et al. (May 2004). "Laboratory diagnosis of SARS". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (5): 825–31. doi:10.3201/eid1005.030682. PMC 3323215. PMID 15200815.

- ↑ Lu P, Zhou B, Chen X, Yuan M, Gong X, Yang G, et al. (July 2003). "Chest X-ray imaging of patients with SARS". Chinese Medical Journal. 116 (7): 972–5. PMID 12890364.

- ↑ "Pandemic Preparedness in the Next Administration: Keynote Address by Anthony S. Fauci". YouTube video- see 27 min. 14 February 2017. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Scientists were close to a coronavirus vaccine years ago. Then the money dried up". NBC News. 8 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ↑ National Center for Biotechnology Information (2009). WHO-recommended handrub formulations. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ↑ "SARS: Prevention". MayoClinic.com. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ "SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome)". 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Offeddu V, Yung CF, Low MS, Tam CC (November 2017). "Effectiveness of Masks and Respirators Against Respiratory Infections in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 65 (11): 1934–1942. doi:10.1093/cid/cix681. PMC 7108111. PMID 29140516.

- ↑ "SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)". nhs.uk. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ "SARS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Harrison's Internal Medicine, 17th ed. Parisianou Publications. pp. 1129–1130.

- ↑ Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner P (September 2006). "SARS: systematic review of treatment effects". PLOS Medicine. 3 (9): e343. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. PMC 1564166. PMID 16968120.

- ↑ Lim WS, Anderson SR, Read RC (July 2004). "Hospital management of adults with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) if SARS re-emerges—updated 10 February 2004". The Journal of Infection. 49 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2004.04.001. PMC 7133703. PMID 15194240.

- ↑ Nakashima E (5 May 2003). "Vietnam Took Lead In Containing SARS". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ↑ Perlman S, Dandekar AA (December 2005). "Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus infections: implications for SARS". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 5 (12): 917–27. doi:10.1038/nri1732. PMC 7097326. PMID 16322745.

- ↑ Jiang S, Lu L, Du L (January 2013). "Development of SARS vaccines and therapeutics is still needed". Future Virology. 8 (1): 1–2. doi:10.2217/fvl.12.126. PMC 7079997. PMID 32201503.

- ↑ "SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)". nhs.uk. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ Greenough TC, Babcock GJ, Roberts A, Hernandez HJ, Thomas WD, Coccia JA, et al. (February 2005). "Development and characterization of a severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody that provides effective immunoprophylaxis in mice". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 191 (4): 507–14. doi:10.1086/427242. PMC 7110081. PMID 15655773. S2CID 10552382.

- ↑ Tripp RA, Haynes LM, Moore D, Anderson B, Tamin A, Harcourt BH, et al. (September 2005). "Monoclonal antibodies to SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV): identification of neutralizing and antibodies reactive to S, N, M and E viral proteins". Journal of Virological Methods. 128 (1–2): 21–8. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.03.021. PMC 7112802. PMID 15885812.

- ↑ Roberts A, Thomas WD, Guarner J, Lamirande EW, Babcock GJ, Greenough TC, et al. (March 2006). "Therapy with a severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody reduces disease severity and viral burden in golden Syrian hamsters". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 193 (5): 685–92. doi:10.1086/500143. PMC 7109703. PMID 16453264.

- ↑ Miller JD (20 January 2004). "China in SARS vaccine trial". The Scientist Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R (July 2004). "SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (7): 1206–12. doi:10.3201/eid1007.030703. PMC 3323345. PMID 15324539.

- ↑ Jinyu M (15 July 2009). "(Silence of the Post-SARS Patients)" (in Chinese). Southern People Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ Monaghan KJ (2004). SARS: Down But Still a Threat. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ↑ "Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003". World Health Organization. 21 April 2004. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ "衛生署針對報載SARS死亡人數有極大差異乙事提出說明". www.cdc.gov.tw (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ↑ Feng D, de Vlas SJ, Fang LQ, Han XN, Zhao WJ, Sheng S, et al. (November 2009). "The SARS epidemic in mainland China: bringing together all epidemiological data". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 14 (s1): 4–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02145.x. PMC 7169858. PMID 19508441.

- ↑ "WHO targets SARS 'super spreaders'". CNN. 6 April 2003. Archived from the original on 7 March 2006. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- ↑ Mawudeku A, Blench M (2005). "Global Public Health Intelligence Network" (PDF). Public Health Agency of Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ↑ Heymann DL, Rodier G (February 2004). "Global surveillance, national surveillance, and SARS". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (2): 173–5. doi:10.3201/eid1002.031038. PMC 3322938. PMID 15040346.

- ↑ Abraham T (2004). Twenty-first Century Plague: The Story of SARS. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801881244. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- 1 2 Kahn J (12 July 2007). "China bars U.S. trip for doctor who exposed SARS cover-up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- 1 2 "The 2004 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee for Public Service". Ramon Magsaysay Foundation. 31 August 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ "SARS death leads to China dispute". CNN. 10 April 2003. Archived from the original on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ↑ Huang, Yanzhong (2004), "THE SARS EPIDEMIC AND ITS AFTERMATH IN CHINA: A POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE", Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak: Workshop Summary, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 19 May 2023

- ↑ Fong K (16 August 2013). "They risked their lives to stop Sars". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ "WHO | Dr. Carlo Urbani of the World Health Organization dies of SARS". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ↑ "Inside the hospital where Patient Zero was infected". South China Morning Post. 27 March 2003. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Griffiths S. "SARS in Hong Kong". Oxford Medical School Gazette. 54 (1). Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ↑ "Hong Kong Residents Share SARS Information Online". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) overview". News Medical Life Sciences. AZO network. 24 April 2004. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016.

- ↑ "Update: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome – Toronto, Canada, 2003". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ Low D (2004). Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak: Workshop Summary.

- ↑ "Is Canada ready for MERS? 3 lessons learned from SARS". www.cbc.ca. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003". World Health Organization (WHO). 31 December 2003. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ↑ Coates S, Anushka A. "Dr Carlo Urbani Health expert who identified the Sars outbreak as an epidemic, and was killed by the virus". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2020.(subscription required)

- ↑ "Dr. Carlo Urbani of the World Health Organization dies of SARS". WHO. 29 March 2003. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ↑ Peiris, JSM; Lai, ST; Poon, LLM; Guan, Y; Yam, LYC; Lim, W; Nicholls, J; Yee, WKS; Yan, WW; Cheung, MT; Cheng, VCC; Chan, KH; Tsang, DNC; Yung, RWH; Ng, TK; Yuen, KY; SARS study group (2003). "Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome". The Lancet. 361 (9366): 1319–1325. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. PMC 7112372. PMID 12711465.

- ↑ Lau, Yu Lung; Peiris, JS Malik (2005). "Pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome". Current Opinion in Immunology. 17 (4): 404–410. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.009. PMC 7127490. PMID 15950449.

- ↑ Normile, Dennis (2003). "Up Close and Personal With SARS". Science. 300 (5621): 886–887. doi:10.1126/science.300.5621.886. PMID 12738826. S2CID 58433622. Archived from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ↑ Poon, Leo LM; Wong, On Kei; Luk, Winsie; Yuen, Kwok Yung; Peiris, Joseph SM; Guan, Yi (2003). "Rapid Diagnosis of a Coronavirus Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)". Clinical Chemistry. 49 (6): 953–955. doi:10.1373/49.6.953. PMC 7108127. PMID 12765993.

- ↑ "Remembering SARS: A Deadly Puzzle and the Efforts to Solve It". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 April 2013. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ "Coronavirus never before seen in humans is the cause of SARS". United Nations World Health Organization. 16 April 2006. Archived from the original on 12 August 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- ↑ Fouchier RA, Kuiken T, Schutten M, van Amerongen G, van Doornum GJ, van den Hoogen BG, et al. (May 2003). "Aetiology: Koch's postulates fulfilled for SARS virus". Nature. 423 (6937): 240. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..240F. doi:10.1038/423240a. PMC 7095368. PMID 12748632.

- ↑ Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ, Liu XL, Zhuang ZX, Cheung CL, Luo SW, Li PH, Zhang LJ, Guan YJ, Butt KM, Wong KL, Chan KW, Lim W, Shortridge KF, Yuen KY, Peiris JS, Poon LL (October 2003). "Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China". Science. 302 (5643): 276–8. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..276G. doi:10.1126/science.1087139. PMID 12958366. S2CID 10608627. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ↑ Kan B, Wang M, Jing H, Xu H, Jiang X, Yan M, Liang W, Zheng H, Wan K, Liu Q, Cui B, Xu Y, Zhang E, Wang H, Ye J, Li G, Li M, Cui Z, Qi X, Chen K, Du L, Gao K, Zhao YT, Zou XZ, Feng YJ, Gao YF, Hai R, Yu D, Guan Y, Xu J (September 2005). "Molecular evolution analysis and geographic investigation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in palm civets at an animal market and on farms". J Virol. 79 (18): 11892–900. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.18.11892-11900.2005. PMC 1212604. PMID 16140765.

- ↑ Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, Ren W, Smith C, Epstein JH, et al. (October 2005). "Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses". Science. 310 (5748): 676–9. Bibcode:2005Sci...310..676L. doi:10.1126/science.1118391. PMID 16195424. S2CID 2971923. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS, Huang Y, Tsoi HW, Wong BH, et al. (September 2005). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (39): 14040–5. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214040L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506735102. PMC 1236580. PMID 16169905.

- ↑ "Scientists prove SARS-civet cat link". China Daily. 23 November 2006. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "The 'Occam's Razor Argument' Has Not Shifted in Favor of a Lab Leak". Snopes.com. Snopes. 16 July 2021. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ Cyranoski D (1 December 2017). "Bat cave solves mystery of deadly SARS virus — and suggests new outbreak could occur". Nature. 552 (7683): 15–16. Bibcode:2017Natur.552...15C. doi:10.1038/d41586-017-07766-9. PMID 29219990.

- ↑ Qiu J. "How China's 'Bat Woman' Hunted Down Viruses from SARS to the New Coronavirus". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Italy and Iran close schools and universities – BBC News". Bbc.co.uk. 4 March 2020. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ↑ "Expert reaction to reports that the (Previously reported) pet dog in Hong Kong has repeatedly tested 'weak positive' for COVID-19 virus | Science Media Centre". Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- 1 2 Morens DM, Fauci AS (September 2020). "Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19". Cell. 182 (5): 1077–1092. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.021. PMC 7428724. PMID 32846157.

- ↑ "SARS 2013: 10 Years Ago SARS Went Around the World, Where is It Now?". 11 March 2013. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "WHO | SARS outbreak contained worldwide". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ Senior K (November 2003). "Recent Singapore SARS case a laboratory accident". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 3 (11): 679. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00815-6. PMC 7128757. PMID 14603886.

- ↑ "Taiwanese SARS researcher infected". 17 December 2003. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ "SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome)". Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ "SARS escaped Beijing lab twice". The Scientist Magazine®. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ "SARS | Guidance | Lab Biosafety for Handling and Processing Specimens | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ↑ Zhan M (March 2005). "Civet Cats, Fried Grasshoppers, and David Beckham's Pajamas: Unruly Bodies after SARS". American Anthropologist. 107 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1525/aa.2005.107.1.031. JSTOR 3567670. PMC 7159593. PMID 32313270. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

Further reading

- Sihoe AD, Wong RH, Lee AT, Lau LS, Leung NY, Law KI, Yim AP (June 2004). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome complicated by spontaneous pneumothorax". Chest. 125 (6): 2345–51. doi:10.1378/chest.125.6.2345. PMC 7094543. PMID 15189961.

- Enserink M (March 2013). "War stories". Science. 339 (6125): 1264–8. doi:10.1126/science.339.6125.1264. PMID 23493690.

- Enserink M (March 2013). "SARS: chronology of the epidemic". Science. 339 (6125): 1266–71. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1266E. doi:10.1126/science.339.6125.1266. PMID 23493691.

- Normile D (March 2013). "Understanding the enemy". Science. 339 (6125): 1269–73. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1269N. doi:10.1126/science.339.6125.1269. PMID 23493692.

External links

| Library resources about SARS |

- MedlinePlus: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome News, links and information from The United States National Library of Medicine

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Symptoms and treatment guidelines, travel advisory, and daily outbreak updates, from the World Health Organization (WHO)

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS): information on the international outbreak of the illness known as a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), provided by the US Centers for Disease Control