| Brucella canis | |

|---|---|

| |

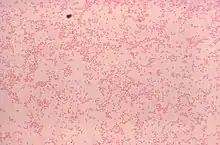

| Gram-stained photomicrograph depicting numerous gram-negative Brucella canis bacteria | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Hyphomicrobiales |

| Family: | Brucellaceae |

| Genus: | Brucella |

| Species: | B. canis |

| Binomial name | |

| Brucella canis Carmichael & Bruner, 1968 | |

Brucella canis is a Gram-negative bacterium in the family Brucellaceae that causes brucellosis in dogs and other canids. It is a non-motile short-rod or coccus-shaped organism, and is oxidase, catalase, and urease positive.[1] B. canis causes infertility in both male and female dogs. It can also cause inflammation in the eyes. The hosts of B. canis ranges from domestic animals to foxes and coyotes.[2] It is passed from species to species via genital fluids. Treatments such as spaying, neutering, and long-term antibiotics have been used to combat B. canis. The species was first described in the United States in 1966 where mass abortions of beagles were documented.[3] Brucella canis can be found in both pets and wild animals and lasts the lifespan of the animal it has affected.[2] B. canis has two distinct circular chromosomes that can attribute to horizontal gene transfer.[4]

Morphology

Brucella are non-motile meaning that they cannot move themselves and they must have assistance. This is because B. canis does not have flagella. Brucella are also non-encapsulated, non-spore forming bacteria that replicate in the ER of their host cells.[5] They are Gram-negative and have a coccobacilli (short rod) shape. They have slightly rounded ends, with slightly outward curving sides.[6] The bacteria form non-hemolytic, non-pigmented convex colonies on blood agar culture media. The optimal growth temperature for B. canis is 37 °C, but growth is still possible within the range from 20 °C to 40 °C. Additionally, the pH range in which B. canis grows most effectively is from pH 6.6 - 7.4, making this organism neutrophilic in nature.[6]

Brucella have an unusual composition of fatty acids that make up their outer cell membrane. Myristic, palmitic, and stearic acids are all found in large quantities within the outer cell membrane. Cis-vaccenic and arachidonic acids are found in medium amounts, while C17 and C19 cyclopropane fatty acids are found in very limited amounts. Additionally, there are no hydroxy fatty acids present in Brucella outer cell membranes. This particular composition of fatty acids is believed to be the reason behind hydrophobic interactions that occur within the outer cell membrane and lead to greater cell stability.[6]

B. canis is also unique from other Brucella species in that the lipids that make up its phospholipid portion are mainly cis-vaccenic cyclopropane with small amounts of lactobaccilic acid. This differs from other Brucella species, as they demonstrate the opposite composition, with lactobacillic acid making up the majority of the phospholipid fraction. Brucella is unusual in this composition because lactobacillic acid is typically within Gram-positive organisms but not common within Gram-negative organisms such as Brucella.[6]

Identification

B. canis is a zoonotic organism. The bacteria are oxidase, catalase and urease positive and non-motile. Unlike haemophilus, which they resemble, they have no requirements for added X (hemin) and V (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) factors in cultures. Full identification is established by serology and PCR. B. canis is not acid-fast, but they tend to maintain their color when exposed to weak acids. This results in their red color when stained using Macchiavello's stain.[6] When isolated, B. canis is always in a non-smooth or mucoid form. This non smooth form has highly hydrophobic LPS imbedded in its outer membrane, which is known to be soluble in phenol-hexane-chlorophorm, rather than phenol-water like smooth forms of Brucella are known to be.[6]

Colonies of Brucella can typically start to be seen after 48 hours. These colonies tend to be 0.5-1.0 mm in diameter, with a convex shape and are typically circular. Mucoid variants such as B. canis have a sticky, glue-like texture, and have a variety of colors. B. canis can present with white, yellowish white, and even brown coloring. This is typical for both mucoid and rough Brucella variants.[6]

Metabolism

B. canis functions as a chemoorganotroph, meaning it obtains its energy from oxidation-reduction reactions, and utilizes organic electron sources. B. canis utilizes oxygen as well as nitrate as its terminal electron acceptor within its electron transport chain. This electron transport system is known to function using cytochromes, and B. canis has the ability to utilize nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor due to the organism's ability to produce nitrate reductase.[6]

While some Brucella species require supplemental CO2 for growth, B. canis does not. B. canis has demonstrated growth on media containing thionine, but no growth on media containing basic fuchsin.[6]

Genome

B. canis has two distinct circular chromosomes. These two circular chromosomes contain shared portions that can be attributed to horizontal gene transfer. The first of the two chromosomes is larger than the second, with an average of 2243 genes on chromosome 1, and 1229 on chromosome 2.[4] Chromosome 2 is much smaller than chromosome 1. Chromosome 2 was derived from a plasmid, but both chromosomes contain genetic information necessary for survival, with these essential genes being split evenly between the two.[7]

B. canis is thought to be a variant of B. suis Biovar 1, based on the genomic similarities between the two. The genomic structure of both B. canis and B. suis Biovar 1, cannot be distinguished from each other as they both demonstrate similar sizes within the two circular chromosomes present. Based on this similarity B. canis is thought to be a stable R mutant of B. suis Biovar 1.[6]

Pathogenicity

The disease is characterized by epididymitis and orchitis in male dogs, endometritis, placentitis, and abortions in females, and often presents as infertility in both sexes. Other symptoms such as inflammation in the eyes and axial and appendicular skeleton; lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, are less common.[8] Although there has been an increase in the international movement of dogs, Brucella canis is still very uncommon.[9] Signs of this disease are different in both genders of dogs; females that have B. canis infections face an abortion of their developed fetuses. Males face the chance of infertility, because they develop an antibody against their spermatozoa. This may be followed by inflammation of the testes which generally settles down a while after. Another symptom is the infection of the spinal plates or vertebrae, which is called diskospondylitis.[10] It is generally spotted in the animal's reproductive organs. This infection usually causes the animal to spontaneously abort a fetus and can also cause an animal to become sterile.[11]

Host range

The host range of the bacterium is mainly domestic dogs but evidence of infections in foxes and coyotes has been reported.[9] B. canis is a zoonotic organism[10] and although rare, humans can contract the infection. It is unlikely, but most common in dog breeders, those in laboratories dealing with the bacteria, or people who are immunocompromised.[12]

Transmission

B. canis is passed through contact with fluids from the mucous membranes of the genitals (semen and vaginal discharge), eyes, and oronasal cavities. This contact can occur during sexual activity as well as other daily grooming and social interactions.

High levels of B. canis exist in these secretions in the six weeks following abortion in females, and around six to eight weeks following infection in males. Lower levels of B. canis still remain in the semen of infected males for two years following infection, which can serve as a large source of transmission to other dogs.[9]

Urine can also serve as a route of transmission in males, as the bladder resides in close proximity to the prostate and epididymus. This leads to contamination of the urine making it another vehicle for B. canis transmission.[13]

Treatment

Treatment for B. canis is very difficult to find and often very expensive. The combination of minocycline and streptomycin is thought to be useful, but it is often unaffordable. Tetracycline can be a less expensive substitute for minocycline, but it also lowers the effect of the treatment.[14]

Long term antibiotics can be given but usually results in a relapse. Spaying and neutering can be effective, and frequent blood tests are recommended to monitor progress. Dogs in kennels that are affected by B. canis are usually euthanized for the protection of other dogs and the humans caring for them.[15]

B. canis is relatively easy to prevent in dogs. There is a simple blood test that can be done by a veterinarian. Any dog that will be used for breeding or has the capability to breed should be tested.

Ecology

Under natural conditions Brucella spp, including B. canis are obligate parasites and do not grow outside the host except in laboratory cultures but at specific temperatures and moisture levels Brucella can persist in soil and surface water up to 80 days and in frozen conditions they can survive for months.[16]

History

B. canis was discovered by Leland Carmichael in 1966, when the bacterium was identified in canine vaginal discharge and the tissues from mass abortions in beagles.[9][17] B. canis was said to be a biovar of B. suis. With recent research, PCR assay data was able to contradict B. canis and B. suis. PCR data showed a complete difference between the two strains along with B. suis biovars unattained from B. canis DNA. PCR assays have been proven beneficial when differentiating between Brucella strains and vaccine strains.[18]

References

- ↑ Mantur BG, Amarnath SK, Shinde RS (July 2007). "Review of clinical and laboratory features of human brucellosis". Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 25 (3): 188–202. doi:10.1016/S0255-0857(21)02105-8. hdl:1807/53456. PMID 17901634.

- 1 2 Kurmanov B, Zincke D, Su W, Hadfield TL, Aikimbayev A, Karibayev T, Berdikulov M, Orynbayev M, Nikolich MP, Blackburn JK (August 2022). "Assays for Identification and Differentiation of Brucella Species: A Review". Microorganisms. 10 (8): 1584. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10081584. PMC 9416531. PMID 36014002.

- ↑ Morisset R, Spink WW (November 1969). "Epidemic canine brucellosis due to a new species, brucella canis". The Lancet. 2 (7628): 1000–1002. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90551-0. PMC 2441019. PMID 4186949.

- 1 2 Wattam, Alice R.; Williams, Kelly P.; Snyder, Eric E.; Almeida, Nalvo F.; Shukla, Maulik; Dickerman, A. W.; Crasta, O. R.; Kenyon, R.; Lu, J.; Shallom, J. M.; Yoo, H.; Ficht, T. A.; Tsolis, R. M.; Munk, C.; Tapia, R. (June 2009). "Analysis of Ten Brucella Genomes Reveals Evidence for Horizontal Gene Transfer Despite a Preferred Intracellular Lifestyle". Journal of Bacteriology. 191 (11): 3569–3579. doi:10.1128/JB.01767-08. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 2681906. PMID 19346311.

- ↑ González-Espinoza, Gabriela; Arce-Gorvel, Vilma; Mémet, Sylvie; Gorvel, Jean-Pierre (2021-02-09). "Brucella: Reservoirs and Niches in Animals and Humans". Pathogens. 10 (2): 186. doi:10.3390/pathogens10020186. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 7915599. PMID 33572264.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bergey, David Hendricks (2001). Bergey's Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-24145-6.

- ↑ Ficht, Thomas (June 2010). "Brucella taxonomy and evolution". Future Microbiology. 5 (6): 859–866. doi:10.2217/fmb.10.52. ISSN 1746-0913. PMC 2923638. PMID 20521932.

- ↑ Brower A, Okwumabua O, Massengill C, Muenks Q, Vanderloo P, Duster M, Homb K, Kurth K (September 2007). "Investigation of the spread of Brucella canis via the U.S. interstate dog trade". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 11 (5): 454–458. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2006.12.009. PMID 17331783.

- 1 2 3 4 Cosford, Kevin L. (2018). "Brucella canis: An update on research and clinical management". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 59 (1): 74–81. PMC 5731389. PMID 29302106.

- 1 2 Forbes JN, Frederick SW, Savage MY, Cross AR (December 2019). "Brucella canis sacroiliitis and discospondylitis in a dog". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 60 (12): 1301–1304. PMC 6855227. PMID 31814636.

- ↑ Canine Brucellosis: Facts for Dog Owners

- ↑ Brucellosis FAQs for Dog Owners. Georgia Division of Public Health in Partnership with the Georgia Department of Agriculture Office of the State Veterinarian, and the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, 13 June 2006, https://agr.georgia.gov/Data/Sites/1/media/ag_animalindustry/animal_health/files/caninebrucellosiskennelanowner.pdf.

- ↑ Hollett, R. Bruce (2006-08-01). "Canine brucellosis: Outbreaks and compliance". Theriogenology. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Society for Theriogenology 2006. 66 (3): 575–587. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.04.011. ISSN 0093-691X. PMID 16716382. S2CID 9154500.

- ↑ Wanke, M. M (2004-07-01). "Canine brucellosis". Animal Reproduction Science. 82–83: 195–207. doi:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.05.005. ISSN 0378-4320. PMID 15271453.

- ↑ Canine Brucellosis and Foster-Based Dog Rescue Programs. Minnesota Department of Health, Jan. 2016, https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/brucellosis/canine.pdf.

- ↑ Xue S, Biondi EG (July 2019). "Coordination of symbiosis and cell cycle functions in Sinorhizobium meliloti" (PDF). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 1862 (7): 691–696. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.05.003. PMID 29783033. S2CID 29166156.

- ↑ Makloski, Chelsea L. (2011-11-01). "Canine Brucellosis Management". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. Companion Animal Medicine: Evolving Infectious, Toxicological, and Parasitic Diseases. 41 (6): 1209–1219. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.08.001. ISSN 0195-5616. PMID 22041212.

- ↑ López-Goñi, Ignacio; García-Yoldi, David; Marín, Clara M.; de Miguel, María J.; Barquero-Calvo, Elías; Guzmán-Verri, Caterina; Albert, David; Garin-Bastuji, Bruno (December 2011). "New Bruce-ladder multiplex PCR assay for the biovar typing of Brucella suis and the discrimination of Brucella suis and Brucella canis". Veterinary Microbiology. 154 (1–2): 152–155. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.06.035. hdl:11056/22276. PMID 21782356.

External links

- Brucella canis genomes and related information at patricbrc.org, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID