| Buckton Castle | |

|---|---|

_(28563211972).jpg.webp) The view across the entrance causeway across the ditch, with the site of the castle behind | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Enclosure castle |

| Town or city | Carrbrook, Stalybridge, Greater Manchester |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53°30′40″N 2°01′04″W / 53.5112°N 2.0178°W |

| Completed | 12th century |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Sandstone |

| Size | 730 square metres (7,900 sq ft) |

Buckton Castle was a medieval enclosure castle near Carrbrook in Stalybridge, Greater Manchester, England. It was surrounded by a 2.8-metre-wide (9 ft) stone curtain wall and a ditch 10 metres (33 ft) wide by 6 metres (20 ft) deep. Buckton is one of the earliest stone castles in North West England and only survives as buried remains overgrown with heather and peat. It was most likely built and demolished in the 12th century. The earliest surviving record of the site dates from 1360, by which time it was lying derelict. The few finds retrieved during archaeological investigations indicate that Buckton Castle may not have been completed.

In the 16th century, the site may have been used as a beacon for the Pilgrimage of Grace. During the 18th century, the castle was of interest to treasure hunters following rumours that gold and silver had been discovered at Buckton. The site was used as an anti-aircraft decoy site during the Second World War. Between 1996 and 2010, Buckton Castle was investigated by archaeologists as part of the Tameside Archaeology Survey, first by the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit then the University of Salford's Centre for Applied Archaeology. The project involved community archaeology, and more than 60 volunteers took part. The castle, close to the Buckton Vale Quarry, is a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Location

Buckton Castle lies 335 metres (1,099 ft) above sea level on Buckton Hill, a steep sandstone ridge (grid reference SD98920162). To the south and west are the valleys of the Carr Brook and River Tame respectively. Buckton Vale Quarry is close to the east of the castle, while the town of Stalybridge is about four kilometres (2 mi) south-west of the site.[1] To the north and north-east of the castle are areas of moorland with heather and peat.[2] The site may have been chosen to allow the castle's garrison to guard the Tame Valley.[3]

During the Middle Ages, Buckton Castle was at the eastern end of Cheshire. The county shares its western border with Wales.[4] Both the castle and valley were in the medieval manor of Tintwistle.[5] A manor was a division of land administered by a Lord of the Manor or his representative;[6] in Tintwistle's case, it was part of the larger lordship of Longdendale.[7][8]

Compared to Herefordshire and Shropshire, which were also on the Anglo-Welsh border, Cheshire has far fewer castles per square kilometre. Most of the county's castles are close to the western border where the historically richer parts of Cheshire are concentrated. The county is mostly lowland, and Beeston is the only other castle in the area that rises as prominently above the surrounding landscape.[4] According to the archaeologist Rachel Swallow, hilltop castles in the area, which include Buckton, Beeston, Halton and Mold, are "predominantly a symbol of significant offensive and elite personal power in these landscapes".[9]

A late 16th-century map of Cheshire; Buckton Castle lies in the north-east of the county.

A late 16th-century map of Cheshire; Buckton Castle lies in the north-east of the county._(28053449473).jpg.webp) The view north-west from Buckton Castle. The castle is on a hill 335 metres (1,099 ft) above sea level.

The view north-west from Buckton Castle. The castle is on a hill 335 metres (1,099 ft) above sea level.

History

Construction and use

The earliest castles in England typically were constructed from timber, at least when they were first built, as building in stone was more expensive. Paleoenvironmental evidence shows that between the 9th and 11th centuries, the area where Buckton Castle would later be built was cleared of woodland. This left little timber, and may partly explain why stone was used as a building material. It became more common to use stone in 12th-century castles, and Buckton is amongst the earliest masonry castles in North West England.[11]

Buckton Castle was probably built in the 12th century and there are three identifiable periods of medieval activity at the site: the initial construction phase, in which the ditch was dug and the curtain wall and gatehouse built; the re-cutting of the ditch and further building work behind the curtain wall; and finally deliberate demolition (slighting). Little datable material has been recovered from the site – four sherds of Pennine Gritty Ware broadly date to the late 12th century.[12]

As is the case with many castles – especially of the 12th century – there is no record of how much it cost to build Buckton Castle. Based on comparison to Peveril Castle in Derbyshire, where construction of the great tower in 1175–1177 cost £184 according to the Pipe Rolls, it is estimated that the work at Buckton would have cost around £100. This was close to the median annual income for a baron in 1200.[13]

Partly because of the cost and partly because Cheshire was a palatine county in which the earl had authority over who was permitted to build castles, it is likely that the castle was built by one of the earls of Chester. Compared to other English counties along the Anglo-Welsh border, Cheshire has fewer castles per square kilometre, indicating that the earl may have limited castle building. The construction of the castle may have been prompted by the earls' involvement in the Anarchy, a civil war during King Stephen's reign in the middle of the 12th century, or the Revolt of 1173–74 against Henry II.[14]

During the Anarchy, David I of Scotland gained control of most of northern England, including the parts of Lancashire, prompting the construction of Buckton Castle to serve as a safeguard for Cheshire.[14] After the Anarchy, many castles were slighted to restore England to its state before the conflict, which may explain why Buckton was demolished. Alternatively, it could have been slighted after the Revolt of 1173–74 to punish the earl of Chester for taking part in a war against the king.[15] While it is likely the earls of Chester built the castle, it is possible it could have been built by William de Neville when he held the lordship of Longdendale under the earl between 1181 and 1186, though he may not have had the financial means to do so.[16]

The dearth of artefacts recovered from Buckton Castle and the lack of finely finished stonework indicate that the site was never finished, but the re-cutting of the ditch suggests either an extended period of occupancy or abandonment followed by repairs to the fortifications.[17]

Later history and investigation

An estate survey from 1360 recorded that "there is one ruined castle called Buckeden and of no value"; this is the earliest surviving reference to the castle.[18] At the time, the lordship of Longdendale was the property of Edward, the Black Prince, and the castle was derelict.[19] The site of the castle may have been used as a beacon in the 16th century, first during the Pilgrimage of Grace of 1536–37, and later in the 1580s when the country was under threat of invasion from Spain, particularly with the Spanish Armada in 1588. This usage may have been reprised in 1803 when a beacon hut is recorded near Mossley, a settlement less than a mile west of the castle.[20]

In the 18th century, people began treasure hunting at Buckton Castle. While the hunting was largely unsuccessful, in 1767 one such venture discovered a gold necklace and a silver vessel, though these artefacts have since been lost.[21] This prompted the interest of local antiquarians, several of whom visited in the 18th and 19th centuries, often drawing plans of the castle.[22] Since 1924, the castle has been designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument,[23] which is intended to protect important archaeological sites from change;[24] this was probably to protect the castle from Buckton Vale Quarry as it expanded.[25] During the Second World War Starfish sites were built as decoys for bombing raids. Nine were built around Manchester, including one close to Buckton Castle. At this time a brick hut was built over part of the castle ditch. The Starfish site went out of use in 1943.[26]

In the 20th century it was suggested that Buckton Castle may have been an Iron Age hillfort, but a study of hillforts in Cheshire and Lancashire found that Buckton was topographically different from these sites and therefore unlikely to have been built in the Iron Age.[27] Excavation in 1998 demonstrated that the site was medieval, with no sign of earlier activity.[2] The archaeologists D. J. Cathcart King and Leslie Alcock suggested that the castle was a ringwork – a type of fortification where earthworks formed an integral part of the defence.[5] This was before excavation established that the first phase of the castle was a curtain wall and the earthworks seen today are the result of the collapse of the structure and accumulation of soil on top. Buckton is now understood to be an enclosure castle, with stone walls forming the key defence.[28]

The Tameside Archaeology Survey began in 1990, carried out by the University of Manchester Archaeology Unit with more than £500,000 of funding from Tameside Council; £300,000 of this was directed towards the excavations at Buckton Castle.[29] A topographical survey and trial excavations were carried out in 1996 and 1998 to record the castle earthworks and examine a possible outer bailey. The latter was revealed to be a 20th-century feature, probably related to nearby mining activity. Illegal digging by unknown parties in 1999 and 2002 necessitated remedial work and test pitting. In 2007, full-scale excavations at Buckton Castle began with the aim of establishing the date and history of the site. Across three seasons – 2007, 2008, and 2010 – trenches were opened across the ditch, the northern entrance, the gap in the circuit of earthworks on the south side, the interior, and the curtain wall.[30]

The University of Manchester Archaeological Unit closed in July 2009, and the Tameside Archaeology Survey, along with the work at Buckton Castle, was transferred to the new Centre for Applied Archaeology at the University of Salford.[31] Brian Grimsditch directed the excavations throughout. More than 60 volunteers were involved in the excavations between 2007 and 2010, including people from the Tameside Archaeological Society, the South Trafford Archaeological Group, the South Manchester Archaeological Research Team, and students from several universities.[32]

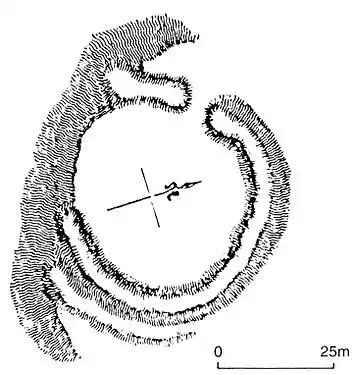

Layout

Buckton was a small highland enclosure castle with a 2.8-metre-thick (9 ft) sandstone curtain wall; nothing survives above ground.[33] It is roughly oval and measures 35.6 by 26.2 metres (117 by 86 ft), covering an area of 730 square metres (0.18 acres). The castle is surrounded by a 10-metre-wide (33 ft) ditch apart from the south-west part where the steep slope of the hill makes the ditch unnecessary. When the ditch was dug some of the material was used to raise the interior of the castle by 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in).[34]

Buckton is similar in size to Clitheroe Castle's inner enclosure, which is also oval (31.8 by 26 metres (104 by 85 ft)) and has a 2.6-metre-thick (9 ft) curtain wall. Clitheroe was also built on a rocky peak and the small size of its great tower may be due to its naturally defensible position and location in an economically deprived area.[35][36]

Buckton Castle was entered through a gatehouse in the north-west measuring 9.3 by 7.5 metres (31 by 25 ft). The east side was occupied by the gate passage and the west by a chamber. Though the structure no longer survives above ground, it was probably at least two storeys tall.[37] Constructed in the 12th century, Buckton's gatehouse was the earliest in North West England, and was one of six stone gatehouses in the region that were built in the 12th or 13th century: Buckton, Egremont, Brough, Clitheroe, Carlisle's inner gatehouse, and the Agricola Tower at Chester. They are broadly similar in size, and take the form of a gate passage piercing a single tower with rooms in the floors above. Buckton's gatehouse differs slightly in having the passage offset to one side.[38]

In the 1770s, the antiquarian Thomas Percival recorded a well within the castle, close to the south curtain, and walls of buildings inside the castle still standing to a height of 2 metres (7 ft). A plan created by the Saddleworth Geological Society in 1842 recorded a ruined structure within the castle's south-east area in addition to the well Percival noted.[22] Trenches in the castle's interior did not reveal the structures on the plans from the 18th and 19th centuries, although the discovery of a posthole indicates there was activity in this area.[39] The gap in the southern part of the curtain wall – not evident in the 1842 plan by the Saddleworth Geological Society – was probably created in the 19th century.[40] There is a feature resembling a spoil heap, consisting of pieces of sandstone. This may have been a by-product from the construction of the castle. Nothing remains of Buckton Castle above ground today, and until the late 20th century, vegetation obscured the existence of a stone structure.[41]

A plan drawn by George Ormerod in 1817

A plan drawn by George Ormerod in 1817 An aerial Lidar plan of the area west of the castle which is far right centre

An aerial Lidar plan of the area west of the castle which is far right centre Part of the ditch surrounding the castle

Part of the ditch surrounding the castle

See also

Notes

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Redhead (2007), p. 5

- 1 2 Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), p. 60

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Redhead (2007), p. 7

- 1 2 Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 41–43

- 1 2 King & Alcock (1969), p. 117

- ↑ Friar (2003), pp. 185–186

- ↑ Nevell & Walker (1998), pp. 48–51

- ↑ Booth (1981), p. 92

- ↑ Swallow (2016), p. 321

- ↑ Eales (2006), p. 23

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 41–44, 85

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 79–80

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 44–47

- 1 2 Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 82–85

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 83–84

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), p. 83

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 81–82

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), p. 87

- ↑ Nevell, Redhead & Grimsditch (2008), p. 32

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 87, 93

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 87–90

- 1 2 Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 90–94

- ↑ Historic England, "Buckton Castle: a ringwork and site of 17th century beacon 350m north east of Castle Farm (1015131)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 25 October 2016

- ↑ Scheduled Monuments, Historic England, retrieved 26 October 2016

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), p. 85

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 95–96

- ↑ Forde-Johnston (1962), pp. 11–12

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), p. 53

- ↑ Lost castle solves riddle of Buckton Moor, University of Manchester, 21 July 2008, retrieved 23 October 2016

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 57–59

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Mitchell (2010), p. 1

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), p. 135

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 47, 55

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), p. 47

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 46–47, 51–52

- ↑ Hartley & Newman (2006), p. 15

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 48, 70–71

- ↑ Nevell (2012–2013), pp. 258, 261, 278

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 76–79

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 70, 93

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 57, 82

Bibliography

- Booth, Paul Howson William (1981), The Financial Administration of the Lordship and County of Chester, 1272–1377, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-71901337-9

- Eales, Richard (2006), Peveril Castle, London: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-982-0

- Forde-Johnston, James (1962), "The Iron Age Hillforts of Lancashire and Cheshire", Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, 72: 9–46

- Friar, Stephen (2003), A Sutton Companion to Castles, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2

- Grimsditch, Brian; Nevell, Michael; Redhead, Norman (September 2007), Buckton Castle: An Archaeological Evaluation of a Medieval Ringwork – an Interim Report, University of Manchester Archaeological Unit

- Grimsditch, Brian; Nevell, Michael; Nevell, Richard (2012), Buckton Castle and the Castles of North West England, University of Salford Archaeological Monographs volume 2 and the Archaeology of Tameside volume 9, Centre for Applied Archaeology, School of the Built Environment, University of Salford, ISBN 978-0-9565947-2-3

- Grimsditch, Brian; Nevell, Michael; Mitchell, Sue (2010), Tameside Archaeological Survey. Annual Report for 2009–10 (PDF), Centre for Applied Archaeology, University of Salford

- Hartley, S; Newman, R (2006), Lancashire Historic Towns Survey Programme: Clitheroe Historic Town Assessment Report, Lancashire County Council

- King, D. J. Cathcart; Alcock, Leslie (1969), "Ringworks of England and Wales", Château Gaillard: Études de castellologie médiévale, 3: 90–127

- Nevell, Michael; Redhead, Norman; Grimsditch, Brian (November 2008), "Buckton Castle", Current Archaeology, Current Publishing, XIX (225): 32–37

- Nevell, Michael; Walker, John (1998), Lands and Lordships in Tameside, Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council with the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 1-871324-18-1

- Nevell, Richard (2012–2013), "Castle gatehouses in North West England" (PDF), The Castle Studies Group Journal, 26: 257–281

- Swallow, Rachel (2016), "Cheshire Castles of the Irish Sea Cultural Zone", The Archaeological Journal, 173 (2): 288–341, doi:10.1080/00665983.2016.1191279, S2CID 163766715

Further reading

- Swallow, Rachel (2018). "Hilltop castles in a medieval landscape: Beeston and Buckton, Cheshire, England". Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. 28: 271–282.

- Walker, John; Nevell, Michael (1999). Tameside in Transition. Tameside Metropolitan Borough with University of Manchester Archaeological Unit. ISBN 1-871324-24-6.