| Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Buffalo Hunters' War | |||||

Caprock Escarpment north of Muchaque Peak | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

| Comanche | ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Nicolas Merritt Nolan | |||||

| Units involved | |||||

| 10th Cavalry | |||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| 4 Soldiers dead + 1 Buffalo hunter deceased | |||||

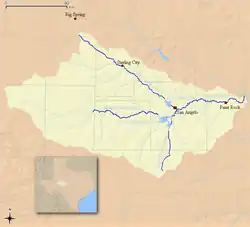

Nolan Expedition vicinity Location within Texas | |||||

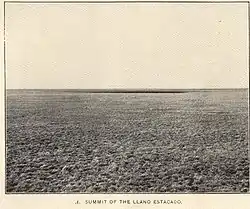

The Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877, also known as the Staked Plains Horror, occurred when a combined force of Buffalo Soldier troops of the United States Army 10th Cavalry and local buffalo hunters wandered for five days in the Llano Estacado region of northwest Texas and eastern New Mexico during July of a drought year, where four soldiers and one buffalo hunter died.

News of the ongoing event and speculation reached East Coast newspapers via telegraphy, where it was erroneously reported that the expedition had been massacred. Later, after the remainder of the group returned from the Llano, the same papers declared them "back from the dead."

Buffalo Hunters' War

A large band of Comanche warriors and their families, about 170, left their reservation in Indian Territory in December 1876, for the Llano Estacado of Texas. In February 1877, they attacked a group of buffalo hunters and stole their stock, while wounding several hunters, one fatally. On March 18, the buffalo hunters struck back and then retreated while the Comanche did the same. The Comanche would continue sporadic raiding over the next several months. This event would be called the Buffalo Hunters' War or Staked Plains War.[1]

Background

In May 1877, a group of buffalo hunters led by James Harvey, a Civil War veteran and long-time buffalo hunter, was looking for a buffalo herd. After a series of Comanche raids led by Red Young Man, where much stock was taken and a few hunters killed, the hunters started looking on the Llano Estacado region of north-west Texas and eastern New Mexico for revenge against the Comanche who had gone far beyond their legal hunting grounds. The men were a mix of former Union and Confederate soldiers, former trappers, and mixed breeds.[2]

Captain Nicolas Merritt Nolan, an Irish native, was one of the 10th Cavalry's favorite officers. He was described as "very fine and soldier-like" with a large, black "overhanging moustache."[3] Nolan had joined the American Army in 1852 as a young 17-year-old rising through the enlisted ranks when he found a niche riding horses. During the Civil War he fought well, received honors and became an officer. After the war he would volunteer for duty with "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 10th Cavalry and command "A" Company (later Troop) for almost a decade and a half.[4]

Nolan had left Fort Concho on July 10, 1877, with a force of 63 officers and men for a scout on the Staked Plains. They were looking for Mescalero Apache and Comanche who were out raiding. Nolan's route took him past the Llano's eastern rugged cap rock northwest toward Bull Creek. Nolan was following a route he had followed northwest in 1875. During that scout, he had followed an Indian trail into the Llano Estacado region until the trail grew cold and he turned back. He had been threatened with court-martial because he was not aggressive enough on that scout. Nolan was deeply shamed by the event. His future patrolling was considered aggressive.[3]

Another event that may have been a factor was the death of Nolan's first wife on February 13, 1877, on the eve of Saint Valentine's Day. This event staggered him, and he was described as "bewildered and forlorn." His daughter Kate attended the Ursuline Academy in San Antonio, and his seven-year-old son Ned was being cared for by a servant. Nolan "bore his cross ... awkwardly" and tried to cope under the loss.[3]

Nolan took command on July 6 of Fort Concho. Grierson had to go east to attend urgent family duties. Almost immediately came orders for the command to go after the Indian raiders. Nolan had already sent C Troop out, so he then went out with A Troop, leaving only one officer and 16 men at Fort Concho. Now en route northeastward along the caprock, Nolan encountered a former scout who reported over 100 Comanche on the Llano Estacado near the head of the North Concho River with a large herd of horses and other stock.[3]

About noon on July 17, Nolan met the buffalo hunters led by James Harvey. One of the key players was the hunters' main guide Jose Piedad Tafoya, a former Comanchero. He knew the Llano well, but was weak in English. With other hunters helping, Tafoya talked to Nolan under the shade of a huge old pecan tree on Bull Creek, which was 7 mi (11 km) east of Muchaque Peak in Borden County, Texas. Nolan showed his orders to the hunters, and despite an initial level of mistrust, they were willing to combine forces.[3]

The bison hunters had had an armed conflict with the Comanche earlier and were looking to recover stock and self-pride. The hunters would guide and supply heavy hitting power while Nolan's soldier would do the fighting and provide medicine and supplies. The hunters wanted their livestock and revenge. Nolan wanted to reprove himself and prove worthy of command that would restore his good reputation. The goal was to find water every 24 hours.[2][3] Nolan set up a supply base at Bull Creek in compliance with his orders. It was across the creek from the buffalo hunter supply base.[3]

The events to follow over the next two weeks resulted in a series of mistakes in command and control combined with civilian distrust. Together with new recruits, the sapping heat, wool uniforms, and alcohol provided by the buffalo hunters to the soldiers, it provided a deadly combination and a test of Nolan and his men. Not all would be seen as heroes. Nolan had prepared for a 20-day scout from his Bull Creek supply base. He used the mules from the wagons as pack animals. He sent the empty wagons back to Fort Concho for more supplies to await his return at the supply base.[3]

On July 18 in the evening, some of the buffalo hunter's supplies, including alcohol, were shared with some of the soldiers for a small price. Some of the sergeants not staying in the supply camp apparently partook. Later the next day, when 40 of the 60 men of A Company set out for Cedar Lake, the sergeants failed to check that every soldier had filled his canteen. In the heat of the day, those who had been drinking the evening before were terribly parched and did not ration their water. Their example led many recruits to drain their canteens. The buffalo hunters carried more water than the soldiers, knowing that the heat and weather would impact finding water. They also were conditioned to the heat and maintained a high level of water discipline.[3]

The Nolan and Harvey combined commands made a dry camp on the evening of July 19. This was where Nolan discovered the lack of water rationing by his men. The hunters were amused; maybe they thought it was a good lesson for the soldiers. The next day led them up Sulphur Draw (Tobacco Creek, Nolan called it) and made the difficult climb up the caprock up onto the "Yarner" of the Llano Estacado. They headed for a large playa the hunters reported was nearby, which they reached on July 21. A playa, or shallow depression, is a basin that fills only when it rains. Cooper estimated this one at about 5 acres (20,000 m2) in size with a maximum depth of 33 inches (840 mm). There, all relished in the water and played. Cooper described the rare event of men of different cultures and races, horses, mules, birds, and other animals enjoying the water as one of the greatest "aggregations of the animal kingdom ever witnessed" "outside a circus tent" in one small place.[3]

Divergent goals

July 18, at about 4:00 in the afternoon in the 100 °F-plus heat, Quanah Parker, a Kwahada leader, rode into camp from the north with two older Comanche couples. They were equipped with Army horses, rifles, supplies, and a large official envelope that contained a pass to leave the reservation for 40 days. It was dated July 12, and signed by the Indian Agent J. M. Haworth at Fort Sill, and more importantly, by Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie of the 4th Cavalry. This pass authorized them to seek out, find, and bring back the large band of Comanche under Red Young Man. The pass also warned anyone against molesting them on their mission.[3][4]

Nolan accepted the pass as real, but his writings show his frustration that Parker was competing for his own mission. Cooper wrote that Nolan swore and let loose a long series of invective-filled frustrations at everyone who seemed to be against 'his' mission. It took him a while to calm down. He then asked Parker questions where the Comanche raiders were and where they were headed. Parker glanced toward one direction and pointed off in a different direction while Tafoya translated. Parker never used English with Nolan, though he spoke it well.[3]

In a three-way conversation, Tafoya talked and translated between Parker and Nolan. The goals of all parties were different. Tafoya and Parker's goal were the most important to them, and despite a history of hostility between them, Tafoya apparently agreed to mislead the soldiers for the return of his stock plus interest. He deliberately translated parts of the conversation wrong to Nolan. Somehow through the three-way conversation and translations, Nolan quickly realized that some type of deal was made between Parker and the interpreter/guide Tafoya. At that point, Nolan began to lose critical trust in his primary trail guide. Later his trust in the hunters also faltered, and maybe, the men who witnessed Nolan's tirade faltered in their own trust of their commander.[3]

After Parker left southward, he was true to his mission and got the Comanche raiders to return to the reservation. Tafoya was true to his word and took the soldiers off the main trail following a false one placed by the Comanche raiders. Tafoya eventually recovered his lost stock and many others. Tafoya later was called "the honest, loyal and gallant company guide" until the truth came out.[3]

After a night march, Nolan, his troopers, and the buffalo hunters reached Cedar Lake about 8:00 AM on July 22. The large 4 by 6 mi (6.4 by 9.7 km) lake in 1875 was now a dry lake. The men dug with cups and slowly obtained water in deep holes dug during the day. The next day Tafoya, Harvey, and Johnny Cook set out on a scout south and west of Cedar Lake. While they were gone, Parker arrived to visit and stayed about six hours. When Tafoya, Harvey, and Cook returned, they reported fresh signs of Indians heading toward Double Lakes. About noon on July 25, they arrived at Double Lakes and found them dry. They dug for water.[3]

Nolan was becoming frustrated because he realized that something was wrong. Many of the buffalo hunters were getting impatient because they believed the Comanche raiders were in the sand hills. They sent out a scout in that direction without the soldiers. Several other hunters called it quits. They were concerned about the "droughty" conditions and perceived that was what was wrong. They pointed out to the soldiers that most of the bison and pronghorn had left the area. This was a sign of a serious drought and "if the rest had good sense, they wouldn't (go further) either."[3]

First Sergeant William L. Umbles was demoted on that day. The exact reasons are uncertain. Some said Nolan was displeased with him. It might have been that Umbles tried to convince Nolan to turn back. It may have been the last straw in Nolan's trust in the first sergeant after the alcohol incident. The two men were silent on the exact reason later, but many agreed Umbles was angry and his behavior showed it during the "thirsting time" to come. The buffalo hunters came back to camp excited at finding a large trail of sign, and Tafoya estimated 40 Comanche in the band near Rich Lake. Boots and saddles were called and the men made haste to get under way. Nolan had not immediately appointed another acting first sergeant, and in his excitement to be underway failed to make sure that all canteens were full. Normally, this is the first sergeant's duty, but it always is the responsibility of the commander to make sure things like this are done.[3]

The "thirsting time"

Day one

July 26, between 2:00 and 3:00 pm, Captain Nolan led his buffalo soldiers with Jim Harvey's bison hunters westward away from Double Lakes. The goal was the trail of 40 Comanche Indians near Rich Lake, 17 miles away. When Nolan's command reached Rich Lake, it had no water. The Indian sign reported by Tafoya was not confirmed by the other scouts. At best, the trail was made by eight horses. Tafoya's goal had started well. Most of the soldiers were out of water, and despite digging in the dry soil, nothing was found. The hunters shared their water sparingly. Tafoya declared that water was available 15 or 20 mi (24 or 32 km) to the northwest in the direction the Indian trail went. Nolan stated they would follow the trail in the morning.[3]

Day two

July 27, just after sunrise the men continued to follow the trail with Sulphur Draw to the left and dry, short-grass stubs here and there. As the miles went on, the reddish soil became "more sandy" and much more effort was needed to move forward. By 9:00 am, the Indians they were following started west, deeper into the void and away from any source of water. Between 2:00 and 3:00 pm after some 25 miles of hard travel, the Indians scattered in eight directions, with criss-crossing trails. The bison hunters' horses were exhausted and the older army horses were worse off. Men were becoming stuporous in the heat. One of the hunters, Johnny Cook, wrote that the Indians "were giving us a dry trail; they would finish us off with thirst." Nolan, aware of the need for water, had scouts checking for possible sources of water for his animals and men. Tafoya and some other scouts found where the Indian trails merged once again. Nolan set off after them. The men suffered in the unrelenting heat. A soldier fainted off his horse from sunstroke, and had to be dealt with. Nolan sent a trooper forward to have the scouts wait for them.[3]

Tafoya stated that the Comanche they were following were headed for Lost Lake (now near Dora, New Mexico) to the northwest, and he loudly declared that the hunters and soldiers would catch them there and have the water, too. The hunters were game, as was Nolan, but a curious change in description of the events was later declared. Johnny Cook's version stated that Nolan was crying and dramatic with the hunters; the hunters felt sympathy for him and agreed to press on. Nolan's version was different, and he wrote that he believed water was to be had some 6 or 7 mi (9.7 or 11.3 km) ahead as reported by Tafoya. Nolan gave Tafoya the best horse to seek out the water. Nolan's claimed crying and weeping does not match his character. He had a goal to follow the Indians and to seek water and that is what he did. Nolan watched as Tafoya left northwestward, then turn suddenly to the west for several miles then toward the northeast. Nolan followed at the pace of the slowest in his command.[3]

Lt. Charles Cooper wrote that he thought the expedition was now lost. He believed that Tafoya was lost, not knowing Tafoya's mission, so under the "broiling sun" and through the "barren sandy plain" the men marched and suffered, and some fell. Nolan then assigned the strongest man to help the weakest. The plan, while noble, was not practical, and the 64 men were soon stretched over 2 mi (3.2 km) of the trail. Near dark and some 9 mi (14 km) of arduous going, Nolan stopped the march.[3]

Nolan now decided on plan B, one that was made earlier by Jim Harvey. Eight men were to move forward following Tafoya's trail to Silver Lake and return with water. Unknown to Nolan, he would not see these men until August 9, and he would never see Tafoya or his horse again. After dark, Nolan pressed the men another 9 mi (14 km) before stopping for the night near a mound called "Nigger Hill." It is located in what is now Roosevelt County, New Mexico, about a mile west of the Texas border. Nolan could hear men down the trail and thinking they were lost, fired shots into the air for them to find camp. Some straggled into camp. Sergeant Umbles, the former first sergeant, was still out in the dark with two sick men. Captain Nolan then had the bugler, also named Nolan, to take a horse and to find and return the men to camp. Those four men never returned. Nolan charged them with desertion upon his return.[3]

Umbles and the others later declared that Captain Nolan had men looking for water, and that was what they were doing. They claimed they found a mule with mud on its legs. Later, they joined with a bison hunter who had chased his runaway horses. They headed for Silver Lake and water. The main body of men after some 55 miles of trail could not eat because of the dryness of their mouths. The bison hunters settled separate from the soldiers. In the dark, they bemoaned their fate with the soldiers. The night without clouds allowed the heat to dissipate and a breeze helped cool the men. Some of the mules, smelling the breeze, took off. The hunters shouted at the soldiers to get their mules, but no one stirred in their exhaustion, and the hunters settled down.[3]

Day three

Just after midnight on July 28, shots being fired woke the men. They did a head count and found one of the hunters missing. Unknown to them, he had joined the four soldiers headed for water. After the alert, the men had a hard time settling down. At daybreak, Nolan came to the conclusion that Tafoya was lost, as were the bison hunters. He may have discussed this with Cooper, but that is not documented. Because of the exhausted men, Nolan himself repacked the remaining mules, deciding what was needed and what could be left. They made some 15 mi (24 km) before Nolan called a halt.[3]

Nolan figured they had missed Silver Lake, so they had no choice but to set a compass course back to Double Lakes. No sign was found of the men sent out for water. Nolan figured his position some 55 mi (89 km) northwest of Double Lakes. He knew for a fact that water was there. Now, the Comanche were forgotten and the primary struggle was for survival. The hunters disagreed, and the expedition began to break up. Nolan argued the best course was to stay together. The hunters strode off then went their different ways focusing on their own goals for survival. The hunters still had two quart bottles of "high-proof brandy", which they divided among themselves and went their ways.[3]

Not all the soldiers agreed to stay together. They began grumbling and thinking that it was going to be every man for himself, as the bison hunters described it. Two men fell behind and were lost to Nolan. Through the pounding heat and endless march, men began to fall. Nolan continued to assign the strongest with the weakest. The desire for water stood above all else, as Nolan headed southeast toward where he knew water was.[3]

Troopers now collected their own urine and that of their horses to drink. Nolan issued sugar for the combination. While urine is generally sterile, it has a high content of electrolytes, which only increased their dehydration and thirst. Just before sunset, Nolan called a halt. He wrote that his men were "completely exhausted". Cooper later wrote, "their tongues and throats were swollen, and they were unable to even swallow their saliva – in fact they had no saliva to swallow." Even sugar poured into their mouths failed to dissolve.[3]

Unknown to Nolan, the men he sent off to find water found some. Several of the soldiers filled the canteens and searched for the command. They found the bison hunters first and gave them water. Then, without finding Nolan, they returned to the waterhole. Unknown to them, Nolan was heading back to Double Lakes. That night, clouds covered the sky and many looked for sign of rain; few found any. Umbles left a note at Silver Lake instructing any soldiers to head east, and those soldiers (sent out for water) returning from the search for the command later did so. Sergeant Umbles was with Jim Harvey at Casas Amarillas that evening. Harvey asked Umbles to let the hunters use the horses, but Umbles refused. The hunters had interpreted that decision as a refusal "to go back to the relief of his officers and comrades." Eventually, 12 soldiers gathered there and headed for safety with two more being found on the way.[3]

Day four

At 2:00 am on July 29, to take advantage of the cool of night, Nolan resumed his heartless track southeast by compass. Nolan had wanted to start earlier, but a horse went down and was unable to move. The men cut its throat and drank its blood. Nolan again repacked what he thought was most important and abandoned the rest. They rode then walked the horses and repeated the process over and over. As the day progressed, the walks got longer because of the condition of the animals. The clouds helped, but no rain fell on Nolan's command on the "Staked Plains". They lost another horse and watched rain appear to fall from whence they had come. After some 25 mi (40 km), they rested from their back-breaking labor through the heat. In their dehydrated exhaustion, several animals walked away and no one noticed. The men were becoming a bit crazed due to the lack of water and the heat. The men were thirsty, but could not drink; they were starving, but could not eat what they had; and now vertigo with dimness of vision began to set in. The men appeared deaf and stuporous, as their bodies began to shut down. Men began to fight over the thick blood cut from the remaining horses. Nolan and Cooper struggled to keep their remaining men alive, and were as harsh as they needed to be. Buffalo hunter Bill Benson also walked away from the command and finally found water about 3:00 pm the next day at Punta del Agua (present day Lubbock Lake) or some 96 hours without water.[3]

Later that day, Nolan and Cooper came to the conclusion that their only hope was to send the strongest men with the remaining horses ahead to Double Lakes. They would remain with the men for better or worse. Nolan ordered now-First Sergeant Jim Thompson to ride ahead with six men and obtain water. Thompson did so, and in the process, five of the seven horses died when he got lost. In the evening, the remaining supplies were abandoned.[3]

Day five

July 30, just after 3:00 am, the men stumbled over an old wagon trail. After stumbling a way along the easier trail, Cooper stopped. Cooper then turned to Nolan and declared that this was Col. William R. Shafter's 1875 wagon trail. It was a route that was between Double Lakes and Punta del Agua. The men rejoiced with harsh shouts and they fired their weapons like it was the Fourth of July. Between 5:00 and 6:00 am, the half-dead soldiers staggered into Double Lakes to the water holes they had dug a week before. The men sent out for water came in last, they had gone over the trail without notice, and turned around when they heard the firing of the other men on the trail. The "thirsting time" was over for them. These 14 men had gone for over 86 hours without any water in the High Plains heat; amazingly, they had survived. Nolan was not finished. He was missing men. After a rest, he sent out men with water to look for stragglers. They found some wandering horses that had been with the bison hunters. They made a diligent hunt for survivors, and recovered what supplies they could. Nolan was still missing men, and he feared many were dead. The men began to recover from their ordeal.[3]

On July 31 at about 11:00 am, Captain Phillip Lee, from Fort Griffin with Troop G, arrived at Double Lakes. He had heard on the 29th that Nolan had been at Double Lakes and he proceeded there. For many of the men, it was a reunion, and Nolan's men told of their ordeal. With Lee's assistance, patrols were sent out looking for the missing men. Other than recovering one man and several horses, nothing else was found.[3]

Most of the buffalo hunters proceeded to the site of present-day Lubbock, Texas, where they found much of their stolen stock. They learned that the Comanche Indians were returning to the reservation with Parker. Tafoya had already claimed his stock and a few others. The hunters later declared this was the last Comanche raid in Texas. The first of them would send out word about Nolan's lost command with the speculation that the Comanche had wiped them out. The story was sent east by telegraph, where it made headline news.[2][3]

Quanah Parker had been true to his word, and had convinced the tired Comanche to go back to the reservation. In the early part of August, they returned to Fort Sill after dropping off their stolen stock. Later, news came out that Parker and Tafoya had misled the buffalo soldiers and bison hunters away from the Comanche raiders. Nolan later was shocked to learn that Parker spoke English fairly well.[2][3]

Sergeant William L. Umbles first headed toward Double Lakes, but changed his course and reached the supply camp at Bull Creek on August 1 with 14 men. Many of the men with him wanted to go to Double Lakes and search for their officers and companions, but Umbles ordered them not to. Despite strong objections, the men followed his commands reluctantly. The Bull Creek supply camp was headed by First Sergeant Thomas H. Allsup. Umbles argued that he was now in command, despite knowing he had been demoted by Nolan. He suggested that Nolan and the other men were dead. Allsup refused to believe it, and wanted to head to Double Lakes with supplies. The men argued, and the two sergeants went their separate ways.[3]

Allsup loaded a wagon with supplies and barrels of water. With 15 men, he proceeded and climbed the caprock and went straight to Doubles Lakes, and on August 4, he had a happy reunion with Nolan and his men. Allsup reported that Umbles had arrived at Bull Creek, and related what he had said. Several other soldiers who had been with Umbles told what had happened over the last few days. Nolan and Cooper began to realize that their problems were not over. Men had deserted and would have to be dealt with. Nolan wrote a message and sent it toward Fort Concho with two riders. The message was a general condition of his command and a warning to distrust anything Umbles and the men with him had to say.[3]

Return

In the evening of August 3, Sergeant Umbles and a few others made it back to Fort Concho. They reported to the sole officer, Lieutenant Robert G. Smithers, that Nolan's command was lost and dead or dying on the Staked Plains. Umbles implied they may have been wiped out. This report caused gloom and doom to spread around the camp. Some people thought the fort would be attacked next. The chaplain went to Mrs. Cooper to break the news that her husband was missing. Then, he went to Nolan's children, who were at Mrs. Constable's home, and comforted them. Smithers then began to send telegrams up the chain of command to other forts. He requested assistance to guard Fort Concho while he sent a relief column out. Smithers gathered men from the band and hospital, and sent 16 effectives and a wagon of supplies for relief of the lost command. They made the 140 mi (230 km) to Bull Creek in 41 hours. He returned between 8:00 and 9:00 AM on August 14 with Nolan and his command.[3][5] On August 7, couriers reached Fort Concho with the good news. The telegraph sent out word that Nolan was returning with his command. The word went east that Nolan and his lost command were "back from the dead." The officer in charge of the relief force now guarding the fort had Umbles and his three companions placed under guard.[3]

For all the men involved, it had been a test of character, which some failed. The cost was high with four soldiers and one civilian dead, about 30 horses and six mules had died during the expedition, and the rest were rendered virtually useless. Nolan's fears for his lost men eventually turned to anger when men came slowly back to Fort Concho and the stories were told. Nolan, as commander of the fort, became very busy ordering new horses and supplies, and preparing for a court-martial for four deserters led by former First Sergeant Umbles. These men were later found guilty and dishonorably discharged, and spent time at Fort Leavenworth Military Prison in Kansas.[3][4]

Nolan wrote his formal report regarding the loss of military equipment, and the deaths and suffering of his men. Many of the events described by Nolan were later found in the letters written home by Lieutenant Cooper, but the documentation left to historians by the buffalo hunters, the soldiers court-martialed, Nolan and Cooper's material led to divergence and more questions. While Nolan's mission was a failure, the press was positive, and he was commended by his superiors in the press, but not officially for the record.[3]

Nolan remained in command of A Troop for another five years. Nolan and his second in command, Lieutenant Cooper, lost their ability to work together over a long series of minor incidents. In late 1879, Nolan placed Cooper on report "for failure to forward personal reports." Cooper went on serving in the military, and retired just after the turn of century as a lieutenant colonel.[3]

On December 19, 1882, Nolan was promoted to major in the Regular Army, and transferred to the 3rd U.S. Cavalry Regiment. On October 24, 1883, he died unexpectedly in Holbrook, Navajo County, Arizona, due to a stroke. His body was shipped to the San Antonio National Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas, where he lies at rest in section A site 53 near the flagpole that flies the flag of his adopted country.[6]

1978 reenactment

In 1978, eight African Americans dressed in cavalry uniforms mounted a horse patrol to retrace the route of Nolan and the Buffalo Soldiers of A Troop. They were led by Eric Strong of the Lubbock-based Roots Historical Committee. They made every effort to camp where the soldiers had stopped 101 years prior.[3]

Author Elmer Kelton traveled with this group for a short time. He was gathering material for a Western fiction book he was writing. This 1986 work, The Wolf and the Buffalo, has two chapters that fairly accurately portray the real-life "Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877."

Historical marker

Remembering the dead soldiers of Troop A, 10th U.S. Cavalry, Captain Nicholas M. Nolan commanding.

- Trooper John H. Bonds, 24, a day laborer from Virginia, enlisted in the Army in Washington, DC, in early 1877.

- Trooper John T. Gordon, 28, joined the Army in Baltimore, Maryland, in December 1876.

- Trooper John Isaacs, 25, a waiter from Baltimore, joined the Army in January 1877.

- Trooper Isaac Derwin, 25, a laborer from South Carolina, joined the Army in Tennessee in November 1876.

The Nolan Expedition route received a historic marker in 1972.[7]

On July 1, 2008, Texas placed a new historical marker to honor the men of the "Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877." Markers were placed for the four fallen soldiers of Company A, 10th Cavalry at Morton Memorial Cemetery. The cemetery is not their burial site, though. The Cochran County Historical Commission had applied for the marker and headstones of the fallen, and money was collected from the community. No mention was made of the death of the white bison hunter.[8] Four additional cenotaph memorials to the 4 Buffalo soldiers are in the San Antonio National Cemetery.

See also

- The Army and Navy Journal dated September 15, 1877 has an article called, "A Fearful march on the Staked Plains" taken from a report of Nicholas M. Nolan. This is cited in Peter Cozzens' volume 3 of his Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890 series with another related report on the subject following. Both reports are stark and clear of the suffering endured.[9]

References

- ↑ Several references for the Buffalo Hunters War. See:

- Dictionary of American History by James Truslow Adams, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940

- The Border and the Buffalo by John R. Cook, 1907, Citadel Press (1967)

- Black Horse from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Battle of Yellow House Canyon from the Handbook of Texas Online

- In 1877, Mackenzie Park was site of a deadly battle Archived 2011-11-03 at the Wayback Machine. Lubbock Online, Nov. 27, 2007

- 1 2 3 4 Nunn, W. C. (1940). "Eighty-Six Hours without Water on the Texas Plains". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. University of North Texas, Austin, Texas: Texas State Historical Association. 43. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

The Handbook of Texas online

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Carlson, Paul H. (2003). The Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-253-4. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Bigelow, John Jr, Lieutenant, U.S.A., R.Q.M. Tenth Cavalry (c. 1890). ""The Tenth Regiment of Cavalry" from "The Army of the United States Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief"". United States Army. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Warfield, H. B., Colonel, USAF retired. (1965). 10th Cavalry & Border fights. El Cajon, CA. LCCN 65-25731.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ San Antonio National Cemetery (2006). "Nicholas M. Nolan, Major US Army". San Antonio National Cemetery. San Antonio National Cemetery web site. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Route of Nolan Expedition - Marker Number: 4370". Texas Historic Sites Atlas. Texas Historical Commission. 1972.

- ↑ Henri Brickey (2009). "New state historical marker honors four Buffalo Soldiers who never made it home". AVALANCHE-JOURNAL. lubbockonline.com. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ↑ Cozzens, Peter (2001). Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890: Conquering the Southern Plains. Vol. 3 of Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865–1890. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0019-1. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

Further reading

- Brady, Cyrus Townsend (1971) [1904]. Indian Fights and Fighters. Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-5743-6.

- Carroll, H. Bailey (1940). "Nolan's 'Lost Nigger' Expedition of 1877". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. University of North Texas, Austin, Texas: Texas State Historical Association. 44. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

The Handbook of Texas online

- Carroll, John M. (1973). The Black Military Experience in the American West (Shorter ed.). New York: Liveright Publishing. pp. 193–198. ISBN 0-87140-090-1.

- Cozzens, Peter (2001). Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890: Conquering the Southern Plains. Vol. 3 of Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865–1890. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0019-1. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- Grierson, Alice (1989). The Colonel's Lady on the Western Frontier - The Correspondence of Alice Kirk Grierson. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska. ISBN 0-8032-7929-9.

- Heitman, Francis B. (1994) [1903]. Historical Register and Dictionary of US Army, 1789–1903, Volume 1 & 2. US Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-8063-1401-3.

- Kinevan, Marcos E., Brigadier General, USAF, retired (1998). Frontier Cavalryman, Lieutenant John Bigelow with the Buffalo Soldiers in Texas. Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso. ISBN 0-87404-243-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leckie, William H. (1967). The Buffalo Soldiers - A Narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma. ISBN 0-8061-1244-1.

- Nunn, W. C. (1940). "Eighty-Six Hours without Water on the Texas Plains". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. University of North Texas, Austin, Texas: Texas State Historical Association. 43. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

The Handbook of Texas online

- Sandoz, Mari (1954). The Buffalo Hunters. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 291–312. ISBN 0-8032-5883-6.

_troops_return_colors_to_Union_League_Club._Men_draw_._._._-_NARA_-_533590.jpg.webp)