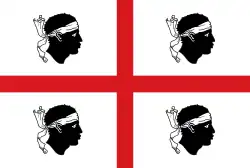

Sardigna | |

|---|---|

| 534 | |

| Capital | Caralis |

| Common languages | Sardinian |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Historical era | Early Middle Ages |

• Established | 534 |

|

| History of Sardinia |

The Byzantine age in Sardinian history conventionally begins with the island's reconquest by Justinian I in 534. This ended the Vandal dominion of the island after about 80 years. There was still a substantial continuity with the Roman phase at this time.

The invasion of the Italian peninsula by the Longobards in 568, which changed the face of Italy, only resulted in a few coastal raids on Sardinia, even if there are traces of their presence on the island, documented by the discovery of various objects, including numerous coins.[1][2]

Administration

The Byzantine Empire was an autocratic state, with its administration centralised around the Emperor. In addition to being the chief of the army he also had authority in the Church, often appointing the Ecumenical Patriarch. Following the Byzantine reconquest, Sardinia was part of the Praetorian prefecture of Africa.[3] The province of Sardinia was ruled by a praeses provinciae, also known as the iudex provinciae, based in Cagliari. A dux was responsible for military matters and was based at Fordongianus (Forum Traiani), which since Roman times had been a fortified bastion against the inhabitants of the Barbagia. These two most important offices, iudex and dux, were unified in the 7th century. To allow for control of the routes that crossed the Tyrrhenian Sea, the island was also home to a squadron of the Byzantine fleet.

_-_Museo_Archeologico%252C_Cagliari_-_Photo_by_Giovanni_Dall'Orto%252C_November_11_2016.jpg.webp)

Units of the Byzantine field army, the comitatenses, were based at Fordongianus. Along the border with the Barbagia region were fortresses such as those at Austis, Samugheo, Nuragus and Armungia. Soldiers of different origins (Germanic peoples, Balkan peoples, Longobards and Avars among others[5]), called limitanei (border troops), were garrisoned here. Some of the island's garrison soldiers were caballarii (horsemen) and received in compensation for their military services land parcels to farm.[6]

In the countryside there continued to be the great estates, but also smaller properties and common lands. The rural population consisted of both free people (the possessors) and slaves, mostly living in villages (vici). They worked the private and community lands with hoes and nail plows, grazed livestock and fished. Extensive vineyards were cultivated but there seemed to have been few orchards.

End of Byzantine rule

Sardinia was initially constituted as a ducatus (duchy) within the Exarchate of Africa. After the fall of the African Exarchate in the 7th century, caused by the Arab conquest of Carthage, the ducatus was directly dependent on Constantinople.

It became then an archontate; that is, a region with the same characteristics of a theme but smaller and less rich. The governors of the island originally held the rank of hypatos and later that of protospatharios, before receiving the title of patrikios from the middle of the ninth century.[7] At this time the relations with Byzantium, if not completely interrupted, had become intermittent, however.[8] Due to Saracen attacks, in the 9th century Tharros was abandoned in favor of Oristano, after more than 1,800 years of human occupation while Caralis was abandoned in favor of Santa Igia. Numerous other coastal centres suffered the same fate (Nora, Sulci, Bithia, Cornus, Bosa, and Olbia among others). Contacts between Sardinia and the Byzantine empire didn't cease, however, as suggested by the mention of Sardinian imperial guards in Constantine VII's work De Caereimoniis (956–959 AD).[9]

The Sardinian archon had both military and civil functions. During the period of direct Byzantine rule, these were delegated to two different officers, the dux and the praeses. The office of archon became the prerogative of a specific family who transmitted the title in succession from father to a son. At the beginning of the 11th century there was a single archon for the whole island. This situation changed over the following decades. The first unequivocal attestation of four separate kingdoms in Sardinia is the letter sent on October 14, 1073 by Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085) to Orzocco of Cagliari, Orzocco d'Arborea, Marianus of Torres, and Constantine of Gallura.[8]

During the early Giudicati era, the Judicate of Cagliari was a direct descendant of the former Archontate of Sardinia. It helped many Byzantine institutions, including the Byzantine Greek language, to survive.[10] By the end of the century Greek had been supplanted by Medieval Latin and Sardinian.

Religion

.JPG.webp)

The Sardinian Church followed the Eastern Rite, in which baptism and confirmation were imparted together. Baptism was carried out by submersion in tanks where water came to the knees of the catechumens. Similar baptismal tanks are found in Tharros, Dolianova, Nurachi, Cornus and Fordongianus. Alongside the secular clergy operated the Basilian monks, who spread Christianity in Barbagia.

In the Byzantine period several cross-in-square churches were erected, with the four arms around a domed roof over their junction.

Chronology

- 534 Conquest of Sardinia by Justinian

- 551-552 Very short occupation of Sardinia by the Ostrogoths of Totila during the Gothic War.

- 565–578 Justin II succeeds Justinian I. Better tax policy.

- 590–604 Pontificate of Pope Gregory I. Letter to the dux Barbaricinorum Hospito for the conversion of the Barbagians.

- 594 Peace between the Byzantines and the Barbagians.

- 599 A Longobard attack on the coast of Cagliari is defeated.

- 603 The papal envoy Vitale is commissioned by the Sardinians to go to Emperor Phocas to demand a reduction in the tax burden.

- 642 Beginning of the Muslim conquest of North Africa.

- 674–678 First Arab Siege of Constantinople

- 698 The conquest of Carthage is a decisive date for the occupation of North-West Africa by the Umayyads; start of the Islamization of that region.

- 705–753 Arab raids

- 827 The Arabs begin the conquest of Sicily; this event is probably relevant in marking a stage in the de facto separation of Sardinia from the Byzantine empire.

References

- ↑ La Sardegna nel Mediterraneo di VII-VIII secolo attraverso il dato archeologico, numismatico e sfragistico (in Italian), retrieved 27 December 2023

- ↑ Monili, ceramiche e monete (bizantine e longobarde) dal mausoleo di Cerredis (Villaputzu-Sardegna) (in Italian), retrieved 27 December 2023

- ↑ Casula 1994, p. 137.

- ↑ "Inscription by Gaudiosus". Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ↑ "Neil Christie, Byzantines, Goths and Lombards in Italy: Jewellery, Dress and Cultural Interactions." (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ↑ Pier Giorgio Spanu, La Sardegna Bizantina fra VI e VII secolo (1998) pg.126-127-128

- ↑ Storia della marineria bizantina, pp. 85–86

- 1 2 Ortu, Gian Giacomo (2005) La Sardegna dei Giudici p.45-46

- ↑ Strinna, Giovanni; Zichi, Giuseppe (30 November 2017). S. Elia di Monte Santo: il primo cenobio benedettino della Sardegna tra storia, arte e devozione popolare. p. 38. ISBN 9788878148208. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ Le iscrizioni greco-bizantine SardegnaCultura.itArchived 2017-10-01 at the Wayback Machine(in Italian)

Bibliography

English

- Consentino, Salvatore. "Byzantine Sardinia between West and East". Millennium: Jahrbuch zu Kultur und Geschichte des ersten Jahrtausends n. Chr. 1 (2004): 329–67.

- Contu, Giuseppe. "Sardinia in Arabic Sources". AnnalSS 3 (2003): 287–97.

- Dyson, Stephen L., and Rowland, Robert J. Archaeology and History in Sardinia from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages: Shepherds, Sailors, and Conquerors. Philadelphia: University of Pennsyolvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2007.

- Galoppini, Laura. "Overview of Sardinia History (500–1500)", pp. 85–114. In Michalle Hobart (ed.), A Companion to Sardinian History, 500–1500. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil. "Gightis and Olbia in the Pseudo-Methodius Apocalypse and Their Significance". Byzantinische Forschungen 26 (2000): 161–67.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil. "Byzantine Sardinia and Africa Face the Muslims: Seventh-Century Evidence". Bizantinistica 3 (2001): 1–25.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil. "Byzantine Sardinia Threatened: Its Changing Situation in the Seventh Century", pp. 43–56. In Paola Corrias (ed.), Forme e Caratteri della presenza bizantina: la Sardegna (secoli VI–XI). Condaghes, 2012.

- Rowland, Robert J. The Periphery in the Center: Sardinia in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2001.

Italian

- Casula, Francesco Cesare (1994). La Storia di Sardegna. Sassari: Delfino.

- Paola Corrias (ed.), Forme e Caratteri della presenza bizantina: la Sardegna (secoli VI–XI), Condaghes, 2012.

- Giorgio Ravegnani, I Bizantini in Italia, Bologna, il Mulino, 2004.

- Storia della marineria bizantina, a cura di Antonio Carile, Salvatore Cosentino, Editrice Lo Scarabeo, Bologna, 2004, ISBN 88-8478-064-0

- Pier Giorgio Spanu, La Sardegna bizantina tra VI e VII secolo, S'Alvure, Oristano, 1998.

- Letizia Pani Ermini, La Sardegna nel periodo vandalico, in AA. VV. Storia dei Sardi e della Sardegna, a cura di Massimo Guidetti, vol. I Dalle origini alla fine dell'età bizantina, Jaca Book, Milano, 1987, pagg. 297–327

- André Guillou, La lunga età bizantina: politica ed economia e La diffusione della cultura bizantina, in AA. VV. Storia dei Sardi e della Sardegna cit., pag. 329–423

- Giuseppe Meloni, Il Condaghe di San Gavino: un documento unico sulla nascita dei giudicati, Cagliari, CUEC, 2005. ISBN 8884672805.

- Giulio Paulis, Lingua e cultura nella Sardegna Bizantina, Sassari, 1983;

- Alberto Boscolo, La Sardegna bizantina e alto-giudicale, Sassari, Chiarella 1978;

- Victor Leontovitsch, Elementi di collegamento fra le istituzioni di diritto pubblico della Sardegna medioevale ed il diritto pubblico dell'Impero bizantino, in "Medioevo. Saggi e rassegne", 3, Cagliari, 1977, pagg. 9–26

- Piras P.G., Aspetti della Sardegna bizantina, Cagliari, 1966.