| CFAP95 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | CFAP95, chromosome 9 open reading frame 135, C9orf135, cilia and flagella associated protein 95 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | MGI: 1914733 HomoloGene: 49850 GeneCards: CFAP95 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

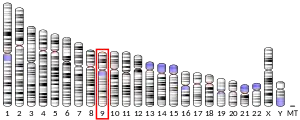

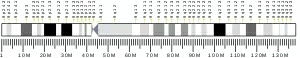

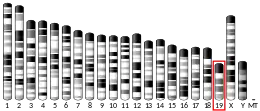

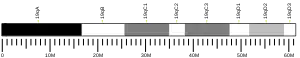

C9orf135 is a gene that encodes a 229 amino acid protein. It is located on Chromosome 9 of the Homo sapiens genome at 9q12.21.[5] The protein has a transmembrane domain from amino acids 124-140 and a glycosylation site at amino acid 75. C9orf135 is part of the GRCh37 gene on Chromosome 9 and is contained within the domain of unknown function superfamily 4572.[6] Also, c9orf135 is known by the name of LOC138255 which is a description of the gene location on Chromosome 9.1.[7]

There is some evidence associating the c9orf135 gene with premature ovarian failure.[8] In affected women, an autosomal recessive microduplication occurs which may be linked to premature ovarian failure. A Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) the c9orf135 gene has been linked to Parkinson’s disease; a statistically significant mutation has been seen on a Manhattan plot.[9] Further research is required to establish whether c9orf135 relates to Parkinson’s disease.[9]

mRNA

The mRNA of c9orf135 is 906 nucleotides in length.[10] The 5' and 3' Untranslated regions (UTR) contain hairpin loops.[11] The 3' UTR comprises 123 nucleotides and the 5' UTR comprises 18 nucleotides. The mRNA encodes a protein with a secondary structure composed of both beta-sheets and alpha-helices.[12]

Secondary structure of c9orf135

Secondary structure of c9orf135 5' UTR loop structure of c9orf135 of mRNA

5' UTR loop structure of c9orf135 of mRNA 3' UTR loop structure of c9orf135 mRNA

3' UTR loop structure of c9orf135 mRNA

Protein

Properties of c9orf135

It is likely that c9orf135 is a nuclear protein because it has properties that match attributes of nuclear proteins rather than secretory pathways.[13][14] Furthermore, there is a nuclear localization signal (PEKVKKL) from amino acid 67 to 73 on c9orf135.[15] C9orf135 is soluble with an average hydrophobicity of -0.772. The negative hydrophobicity value is due to its slightly acidic properties.[16]

Post-translational modifications

Serine phosphorylation sites were seen at amino acid positions 7, 50, 86, 98, and 194. Threonine phosphorylation occurs at 34, 129, 155, and 201. Tyrosine phosphorylation sites occur at 78, 160, 177, and 209. Also, a N-terminal acetylation site is present at amino acid 3. A Signal cleavage site is present between amino acids 11 and 12.[17]

Protein Interaction

PB2 interacts with c9orf135 which was found from a two-hybrid yeast assay. The information provided about PB2 (Polymerase Basic Protein 2) is that it is a viral protein that is involved with the influenza A virus. It is primarily involved in Cap stealing in which it binds the pre-mRNA cap an ultimately cleaves 10-13 nucleotides off. PB2 is also important for starting the replication of viral genomes. PB2 is also known to inhibit type 1 interferon by inhibiting the mitochondrial antiviral signalling protein MAVS.[18]

Mutations

Eleven different common DNA genome variants of the human c9orf135 gene have been identified. All of the mutations within those genome variants have been compiled into the following table.[19] Mutations that were present at levels of 0.01 frequency or higher have been incorporated into the table; synonymous mutations were excluded.

| Location | Amino Acid Position | Mutation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5' UTR | 57 | N/A | 0.386 |

| 5' UTR | 93 | N/A | 0.047 |

| 5' UTR | 138 | N/A | 0.018 |

| Exon | 169 | Missense K30T | 0.018 |

| Exon | 237 | Missense R53K | 0.047 |

| Exon | 456 | Missense E126K | 0.01 |

Gene Expression

c9orf135 is expressed in connective tissue and testicular tissue at high levels.[20] It is likely that the expression of c9orf135 is expressed at low levels throughout human cells. It was also found that c9orf135 is found at significantly higher levels in the adult human umbilical cord versus the foetal human umbilical cord.[21] Furthermore, in women with ovarian adenocarcinoma the expression of c9orf135 is much higher in the epithelial cells within the ovaries.[22] Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome have a lower expression of c9orf135 than those people who do not have the condition.[23]

Fetal and Adult Umbilical cord expression

Fetal and Adult Umbilical cord expression Ovarian normal surface epithelia and ovarian cancer epithelial cells

Ovarian normal surface epithelia and ovarian cancer epithelial cells Polycystic ovarian syndrome versus obese women regarding c9orf135.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome versus obese women regarding c9orf135.

Amino Acid Quantity

A comparison between the c9orf135 from Mus musculus (House Mouse) and Pteropus alecto (Black Flying Fox) is described here. There were no significant amino acids that differed in c9orf135 from the rest of the mouse body. However, in the Black Flying Fox, it was valine poor and tryptophan rich. As seen from the human results, the Black Flying fox only shared the tryptophan surplus results. The House Mouse and Black Flying Fox were both used because they shared 64% and 79% similarity in the c9orf135 genome respectively. Analysis demonstrates that alanine and tyrosine could predict points of interest because they both contained results differing from the rest of the human gene averages.[16]

| Amino Acid of Interest | Compositional Percentage |

Compared to normal protein amounts in H. sapiens |

|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 3.1% | Less than Average |

| Tyrosine | 5.2% | More than Average |

| Trytophan | 3.1% | More than average |

Homology

c9orf135 is conserved through eukaryotes, ranging from mammals, reptiles and Annelida.

Orthologs

The orthologs of c9orf135 were sequenced in BLAST and 20 orthologs were picked. The orthologs were all multicellular organisms and were limited to aquatic animals, reptiles, amphibians, and warm-blooded animals. Also, protists, bacteria, archea, and fungi did not have orthologs. However, no paralogs were found when c9orf135 was sequenced in BLAST. Please refer to the spreadsheet for the complete list of orthologs to c9orf135. Time tree was a program that was used to find the evolutionary branching shown in MYA[24] There were no paralogs found for c9orf135.

| Genus/Species | Common name | Divergence from Humans (MYA) | Accession number | Amino Acid Length | Sequence identity | Sequence similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | Human | -- | Q5VTT2 | 229 | -- | -- |

| Pongo abelii | Sumatran Orangutan | 15.8 | XP_002819904 | 206 | 86% | 87% |

| Rhinopithecus roxellana | Golden Snub-Nosed Monkey | 29.1 | XP_010361250 | 229 | 93% | 95% |

| Mus musculus | House Mouse | 90.9 | EDL41604 | 228 | 64% | 73% |

| Pteropus alecto | Black Flying Fox | 97.5 | XP_785964 | 230 | 79% | 86% |

| Equus przewalskii | Przewalski's horse | 97.5 | XP_008504806 | 183 | 77% | 86% |

| Panthera tigris altaica | Siberian Tiger | 97.5 | XP_007077537 | 187 | 73% | 83% |

| Ovis aries | Sheep | 97.5 | XP_014948670 | 207 | 69% | 77% |

| Elephantulus edwardii | Cape Elephant Shrew | 105 | XP_006894485 | 254 | 72% | 82% |

| Pelodiscus sinensis | Chinese Softshell Turtle | 320.5 | XP_006137902 | 217 | 55% | 68% |

| Gekko japonicus | Gekko | 320.5 | XP_015275999 | 221 | 52% | 64% |

| Alligator mississippiensis | American Alligator | 320.5 | XP_014464144 | 212 | 51% | 64% |

| Ophiophagus hannah | King Cobra | 320.5 | ETE61720 | 215 | 43% | 59% |

| Salmo salar | Atlantic Salmon | 429.6 | XP_013998840 | 99 | 34% | 55% |

| Esox lucius | Northern Pike | 429.6 | XP_010901691 | 154 | 30% | 47% |

| Branchiostoma floridae | Lancelet | 733 | XP_002591786 | 221 | 45% | 59% |

| Strongylocentrotus purpuratus | Sea Urchin | 747.8 | XP_785964 | 241 | 47% | 62% |

| Saccoglossus kowalevskii | Acorn Worm | 747.8 | XP_002733410 | 153 | 38% | 58% |

| Lingula anatina | Ocean Clam | 847 | XP_013398605 | 220 | 43% | 59% |

| Crassostrea gigas | Pacific Oyster | 847 | XP_011426944 | 215 | 40% | 57% |

| Helobdella robusta | Leech | 847 | XP_009019861 | 256 | 29% | 44% |

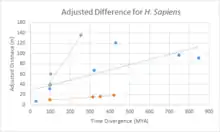

Divergence of c9orf135

A divergence comparison of c9orf135 with fast diverging cytochrome C, and slow diverging fibrinogen is shown in the chart. Overall, c9orf135 has diverged significantly quicker than fibrinogen and slightly slower than cytochrome C.

References

- 1 2 3 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000204711 - Ensembl, May 2017

- 1 2 3 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000033053 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ "Q5VTT2.1". NCBI, Protein.

- ↑ "BLAST protein sequence, c9orf135".

- ↑ Result Filters. (n.d.). Retrieved February 07, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/Q5VTT2.1 Archived 2018-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ McGuire MM, Bowden W, Engel NJ, Ahn HW, Kovanci E, Rajkovic A (April 2011). "Genomic analysis using high-resolution single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays reveals novel microdeletions associated with premature ovarian failure". Fertility and Sterility. 95 (5): 1595–600. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.052. PMC 3062633. PMID 21256485.

- 1 2 Chung SJ, Armasu SM, Biernacka JM, Anderson KJ, Lesnick TG, Rider DN, Cunningham JM, Eric Ahlskog J, Frigerio R, Maraganore DM (August 2012). "Genomic determinants of motor and cognitive outcomes in Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 18 (7): 881–6. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.04.025. PMC 3606821. PMID 22658654.

- ↑ NCBI, Nucleotide, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/809279636?report=fasta Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Sfold, Srna, http://sfold.wadsworth.org/cgi-bin/showcentroid.pl Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ I-Tasser, http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/ Archived 2020-02-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ YLoc http://abi.inf.uni-tuebingen.de/Services/YLoc/webloc.cgi?id=86ac5008fd25bd20a065f49a970fd19c Archived 2016-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ SOSUI Classification and Secondary Structure Prediction of Membrane Proteins, http://harrier.nagahama-i-bio.ac.jp/sosui/ Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ PSORT II, PSORT II Prediction, http://psort.hgc.jp/cgi-bin/runpsort.pl%5B%5D

- 1 2 SDSC Biology Workbench, SAPS, http://seqtool.sdsc.edu/CGI/BW.cgi#%5B%5D!

- ↑ ExPasy, Sibs bioinformatics analysis, http://www.expasy.org/ Archived 2018-01-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "1 binary interaction found for search term C9orf135". IntAct Molecular Interaction Database. EMBL-EBI. Archived from the original on 2018-08-25. Retrieved 2018-08-25.

- ↑ NCBI SNP Geneview https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?geneId=138255&ctg=NT_008470.20&mrna=XM_011518232.1&prot=XP_011516534.1&orien=forward Archived 2018-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ EST profile, NCBI, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NM_001308086.1 Archived 2016-09-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Geo Profile, NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles/78193260 Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Geo Profile, Ovarian normal surface epithelia and the ovarian cancer epithelial cells, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/tools/profileGraph.cgi?ID=GDS3592:236519_at Archived 2018-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Geo Profile, Obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and obese, healthy women: skeletal muscle, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/tools/profileGraph.cgi?ID=GDS4133:243610_at Archived 2018-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hedges SB, Marin J, Suleski M, Paymer M, Kumar S (April 2015). "Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (4): 835–45. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv037. PMC 4379413. PMID 25739733.