Cairook | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mohave leader | |

| Preceded by | Unknown |

| Succeeded by | Irataba |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Unknown Alta California, New Spain |

| Died | June 21, 1859 Fort Yuma, California |

| Cause of death | Killed by US soldiers while trying to escape imprisonment |

| Known for | navigational prowess, leadership of Mohave people |

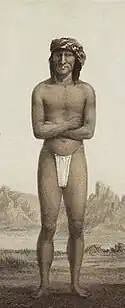

Cairook, also known as Avi Havasuts ("Blue Rock") was a Mohave leader born sometime before 1814.[1]

In 1854, Cairook accompanied the Whipple expedition from the Colorado River to Afton Canyon on the Mojave Road, guiding them successfully through the area now known as the Mojave National Preserve. Amiel Weeks Whipple appreciated Cairook's help, and found Cairook to be a willing and fair trader with his party. [2]

Other American explorers and surveyors spoke highly of Cairook, including Charles Ives, who wrote in his journal entry on March 23, 1858 that "Cairook came to bid us farewell. I was never before so struck with his noble appearance. When he shook hands his head was almost level with mine as he stood beside the mule on which I was riding. He indicated his wishes that we might have a successful trip, and remained watching the train until it was out of sight, waving his hand and smiling his adieus. We all felt regret at parting with him, for he had proved himself a staunch friend."[3] According to Fulsom Charles Scrivner, author of Mohave People (1970), Cairook grew to a height of nearly 6 feet 6 inches (198 cm).[4]

In 1858, an attack on the Rose-Baley Party began the series of events that led to Cairook's death at the hands of American Army officials. The party arrived in late August 1858, arriving along the Colorado River. L.R. Rose, one of the leaders, reported that the Mojaves were very friendly, aiding the tired travelers throughout the evening. [5] The travelers camped along the Colorado River, and on August 29, Mojave leaders Cairook and Sickahot went to inquire after the travelers, asking if they intended to settle on their Mojave territory or travel onward. On August 30, the traveling party was attacked by Hualapais and seven Mohaves after felling many of the Mojave cottonwood trees along the Colorado River and grazing their cattle on Mojave territory.[6] The remaining Rose-Baley Party members fled.

After the attack on the Rose-Baley Party, General N.S. Clarke, the commander of the Military Department of California (headquartered in San Francisco) was convinced that a military post should be constructed at Fort Mojave in order to prevent a general Indian uprising, which he believed was spurred by the encouragement of Mormon emigrants.[7] Clarke sent Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman and 50 men of the First Mohave Expedition sent to Beale's Crossing to build a post for ensuring military power along the Colorado River.

Although initial contact with the Mojaves was friendly,[8] the continued presence of soldiers worried the Mojaves that soldiers were encroaching on their territory in the fertile Mojave Valley over a period of several days in January, 1859. After the initial friendly meetings, Hoffman warned Mojaves to stay away from their camp at night, or risk being shot. He moved his camp to the Colorado River. One night, Hoffman reported that sentinels shot at several Mojaves and Paiutes (most likely Chemehuevis). He reflected "The hostile attitude taken by the Indians left little room to doubt that we could not remain another twenty-four hours in the valley without a collision with the Mohave Nation."[9]

Hoffman decided to attack the Mojaves the following day, killing at least ten Mojaves. Hoffman and his group left for Fort Yuma in order to prepare to bring a show of military force back to Mojave territory. Hoffman demanded that the tribe surrender to US forces, naming the following conditions that he later wrote in a letter to General Clarke on April 24, 1859: "1st. The must offer no opposition to the establishment of posts and roads in and through their country, when and where the government chooses; and the property and lives of whites travelling through their country must be secured. 2nd. As security for their future good conduct they must place in my hands one hostage for each of the six bands. 3rd. They must place in my hands the chief who commanded at the threatened attack on my camp in January last. 4th. They must place in my hands three of those who were engaged in the attack on the emigrant part at this spot last summer".[10]

Cairook was one of the Mojaves who agreed to be taken hostage by the U.S. Government at Fort Yuma. By late June, the imprisoned Mojaves were sick of being held hostage. After Mojave leader Irataba visited to petition for Cairook's release and was refused, Cairook and the other hostages planned their escape.[11] Cairook's role in the escape was to hold the sentry, and he was subsequently bayoneted while the others escaped. [12] According to Mojave elder Frances Stillman, Cairook had told the other men imprisoned "You're all young. I'm years ahead of you. I've had a lot of years already that I've spent of my life. When its lunch time, all the guards go to their lunch except that one up there. I'll go up and hold him while you men dive into the water."[13]

References

- ↑ Scrivner 1970, p. 127–32.

- ↑ Sherer 1994, pp. 54–63.

- ↑ Quoted in Sherer 1994, pp. 100–101

- ↑ Scrivner 1970, pp. 127–28.

- ↑ Cleland 1951, pp. 266–267.

- ↑ Sherer 1994, pp. 85, 95.

- ↑ Sherer 1994, p. 87.

- ↑ Hoffman quoted in Sherer 1994, p. 89

- ↑ Hoffman quoted in Sherer 1994, p. 91

- ↑ Hoffman quoted in Sherer 1994, p. 95

- ↑ Ives quoted in Sherer 1994, p. 101

- ↑ Scrivner 1970, pp. 133–34.

- ↑ Stillman quoted in Sherer 1994, p. 102fn6

Bibliography

- Scrivner, Fulsom Charles (1970). Mohave People. The Naylor Company. ISBN 978-0-8111-0335-0.

- Sherer, Loraine M. (1994). Bitterness Road. Ballena Press. ISBN 0-87919-128-7.

- Cleland, Robert Glass (1951). The Cattle on a Thousand Hills: Southern California, 1850-1880. Huntington Library.