Callan

Callainn | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Green Street, Callan, at sunset | |

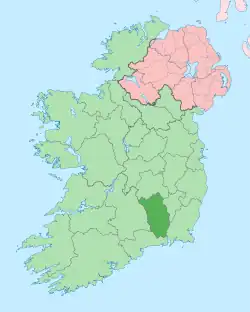

Callan Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 52°33′00″N 7°23′00″W / 52.55°N 7.383333°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | County Kilkenny |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5 km2 (2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 65 m (213 ft) |

| Population | 2,475 |

| Irish Grid Reference | S410440 |

Callan (Irish: Callainn)[2] is a town and civil parish in County Kilkenny in Ireland. Situated 16 km (10 mi) south of Kilkenny on the N76 road to Clonmel, it is near the border with County Tipperary. It is the second largest town in the county, and had a population of 2,475 at the 2016 census.[1] Callan is the chief town of the barony of the same name.

History and name

Callan was founded by William the Marshal in 1207 and reputedly gets its name from the High King of Ireland, Niall Caille. It is reported that while at war with the Norsemen the High King arrived in Callan to find that its river was in flood. The King witnessed his servant trying to cross the river and being swept away by the fast-flowing current. The King, recorded in history as a man of action, seeing the impending disaster, impetuously urged his horse into the fast flowing river in a vain bid to save his servant, only to be also overcome and drowned by the torrent. The river in question is now named the "Kings River". The town received its first charter in 1217 and was entitled to choose two elected members of Parliament.[3]

In 1650, Oliver Cromwell and his New Model Army laid siege to Callan.[4] Although Sir Richard Talbot, the commander of the main defence had secretly organised to surrender, some of the other defenders refused to do so, leading to a battle for the town. All of the defenders and many of the townspeople who sought safety in the stone castle and parish church were killed. In the late 19th century, a large number of human bones and cannon balls were discovered during excavations of the ruins of the old parish church.[5]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 3,111 | — |

| 1851 | 2,368 | −23.9% |

| 1861 | 2,331 | −1.6% |

| 1871 | 2,387 | +2.4% |

| 1881 | 2,340 | −2.0% |

| 1891 | 1,973 | −15.7% |

| 1901 | 1,840 | −6.7% |

| 1911 | 1,987 | +8.0% |

| 1926 | 1,500 | −24.5% |

| 1936 | 1,516 | +1.1% |

| 1946 | 1,545 | +1.9% |

| 1951 | 1,506 | −2.5% |

| 1956 | 1,461 | −3.0% |

| 1961 | 1,346 | −7.9% |

| 1966 | 1,263 | −6.2% |

| 1971 | 1,283 | +1.6% |

| 1981 | 1,431 | +11.5% |

| 1986 | 1,266 | −11.5% |

| 1991 | 1,246 | −1.6% |

| 1996 | 1,224 | −1.8% |

| 2002 | 1,325 | +8.3% |

| 2006 | 1,771 | +33.7% |

| 2011 | 2,330 | +31.6% |

| 2016 | 2,475 | +6.2% |

| [6][7][8][9][10][1] | ||

In order to commemorate those who died in the Callan area during World War One, a statue was erected outside the Church of the Assumption on Green Street.

In 2007, Callan celebrated its 800th year. President Mary McAleese launched the 800th celebrations of the town being granted a charter.

Places of interest

Callan Motte (also known locally as simply "The Moat") is located at the top of Moat Lane just off Bridge Street. It is one of Ireland's best-preserved Motte-and-bailey's.

Callan Augustinian Friary, known locally as the "Abbey Meadow", is at the North-East end of Callan and can also be accessed via Bridge Street.

St. Mary's Church is a medieval church located on Green Street. A historic workhouse is located in Prologue.

Education

Callan had two primary schools, Scoil Mhuire and Scoil Iognáid Rís. The two schools amalgamated in 2007 to form Bunscoil McAuley Rice. Callan also has two secondary schools; the boys' school, Coláiste Éamann Rís, and the girls', St. Brigid's College.

Callan local electoral area

The Callan–Thomastown local electoral area of County Kilkenny includes the electoral divisions of Aghaviller, Ballyhale, Ballyvool, Bennettsbridge, Boolyglass, Bramblestown, Brownsford, Burnchurch, Callan Rural, Callan Urban, Castlebanny, Coolaghmore, Coolhill, Danesfort, Dunbell, Dunnamaggan, Dysartmoon, Earlstown, Ennisnag, Famma, Freaghana, Graiguenamanagh, Grange, Inistioge, Jerpoint Church, Kells, Kilfane, Killamery, Kilmaganny, Kiltorcan, Knocktopher, Mallardstown, Outrath, Pleberstown, Powerstown, Rosbercon Rural, Scotsborough, Stonyford, The Rower, Thomastown, Tullaghanbrogue, Tullaherin, Tullahought, Ullard and Woolengrange.[11]

In popular culture

Neil Jordan's film Breakfast on Pluto with Cillian Murphy and Liam Neeson was filmed in Callan during August–September 2005. During the two weeks of filming in Callan, the main streets of the town were transformed for use in the film.

Callan was the set and stage for The Big Chapel X, a large-scale theatre production and community engagement project that drew on the history of the Callan schism, in August 2019, created by Asylum Productions in partnership with the Kilkenny Arts Festival supported by the Abbey Theatre and the Arts Council. Callan boasts many arts organisations including KCAT Arts Centre, Workhouse Union, Monkeyshine, Trasna Productions and Fennelly's Cafe.

People

Callan is the birthplace of a number of famous people, including:

- Edmund or Edward Butler (died 1584), a member of the Butler dynasty, Attorney General for Ireland and a justice of the Court of King's Bench (Ireland), lived in Callan for most of his life.

- Gerald Comerford (died 1604), the principal landowner in Callan in the late sixteenth century and also an influential politician and judge; his tomb can still be seen at St Mary's Church

- Patrick Cudahy (1849–1919), American industrialist and philanthropist

- James Hoban who designed The White House and Leinster House among others was born in Desart, near Callan.

- Linda Hogan (born 1964), Professor of Ecumenics at Trinity College Dublin, and its former vice-provost

- Edmund Ignatius Rice, founder of the Irish Christian Brothers and the Presentation Brothers

- Thomas Kilroy Irish playwright and novelist. Author of the historical novel The Big Chapel.

- John Locke, Ireland's Poet in Exile, was born here in 1847.[12]

- Seamus Moore (singer), Irish singer/songwriter

- Thomas Nash (Newfoundland) Irish fisherman, settled in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Founder of Branch, Newfoundland and Labrador[13]

- Tony O'Malley, Irish painter

- Amhlaoibh Ó Súilleabháin (1780–1838), was a schoolmaster and linen-draper in the town, and kept a diary in the Irish language between 1827 and 1835. This recorded in great detail the life of the town. Amhlaoibh's diary is considered one of the most detailed contemporary accounts of life in Ireland at the time.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Sapmap Area - Settlements - Callan". Census 2016. Central Statistics Office Ireland. April 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ↑ "Callainn/Callan". Placenames Database of Ireland (logainm.ie). Government of Ireland. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ↑ Walsh, Dr. F.R. "Callan 'Olde' Parish Church" (PDF). Kilkenny Archaeological Society. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ McQuillan, Peter (7 April 2018). "Cromwell in Callan". Kilkenny Archaeological Society. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ Walsh, Dr. F.R. "Callan 'Olde' Parish Church" (PDF). Kilkenny Archaeological Society. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ Census for post 1821 figures.

- ↑ "Histpop - The Online Historical Population Reports Website". www.histpop.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency - Census Home Page". Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ↑ Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J.M.; Clarkson, L.A. (eds.). Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700-1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. hdl:10197/1406. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- ↑ County of Kilkenny Local Electoral Areas and Municipal Districts Order 2018 (S.I. No. 621 of 2018). Signed on 19 December 2018. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book.

- ↑ Local History of Callan Archived 2007-11-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "The Hearth Municipal Heritage Site". Canada's Historic Places. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

Further reading

- Walsh, F. R. (1952). "Callan". Old Kilkenny Review: 16–22.

- Walsh, F. R. (1963). "Callan Olde Parish Church". Old Kilkenny Review: 14–18.

- O'Brien, Seamus (1979). "Callan Electricity Board". Old Kilkenny Review: 48–49.

- Phelan, Margaret (1980). "Fr Thomas O'Shea and the Callan Tenant Protection Society". Old Kilkenny Review: 49–58.

- Phelan, Margaret (1982). "Callan Doctors". Old Kilkenny Review: 364–368.

- O'Doherty, Sean (1981). "Repeal in Callan Workhouse". Old Kilkenny Review: 226–230.

- Kennedy, Joe (1984). "Cromwell in Callan". Old Kilkenny Review: 47–51.

- Kennedy, Joseph (1988). "Thomas Shelly of Callan (1823-1905) His Life and Times". Old Kilkenny Review: 492–502.

- Kennedy, Joseph (1991). "Coca-Cola (The Callan Connection)". Old Kilkenny Review: 885–894.

- Kealy, Carmel (1986). "Callan in the early 20th century". Old Kilkenny Review: 299–301.

- Kealy, Carmel (1987). "Callan Memories". Old Kilkenny Review: 379–383.

- Hogan, Patrick (1987). "The Callan Schism 1869-1879". Old Kilkenny Review: 339–357.

- Clutterbuck, Richard, Ian Elliot & Brian Shanahan (2006). "The Motte and Manor of Callan, County Kilkenny". Old Kilkenny Review: 7–28.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grace, Pierce A. (2011). "'Much Like Yesterday' - Callan Folklore in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries". Old Kilkenny Review: 58–63.