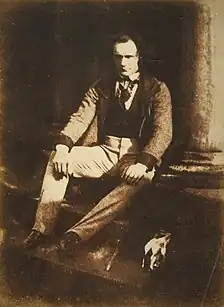

Calotype or talbotype is an early photographic process introduced in 1841 by William Henry Fox Talbot,[1] using paper[2] coated with silver iodide. Paper texture effects in calotype photography limit the ability of this early process to record low contrast details and textures. The term calotype comes from the Ancient Greek καλός (kalos), "beautiful", and τύπος (tupos), "impression".

The process

Talbot made his first successful camera photographs in 1835 using paper sensitised with silver chloride, which darkened in proportion to its exposure to light. This early "photogenic drawing" process was a printing-out process, i.e., the paper had to be exposed in the camera until the image was fully visible. A very long exposure—typically an hour or more—was required to produce an acceptable negative.

In late 1840, Talbot worked out a very different developing-out process (a concept pioneered by the daguerreotype process introduced in 1839), in which only an extremely faint or completely invisible latent image had to be produced in the camera, which could be done in a minute or two if the subject was in bright sunlight. The paper, shielded from further exposure to daylight, was then removed from the camera and the latent image was chemically developed into a fully visible image. This major improvement was introduced to the public as the calotype or talbotype process in 1841.[3]

The light-sensitive silver halide in calotype paper was silver iodide, created by the reaction of silver nitrate with potassium iodide. First, "iodised paper" was made by brushing one side of a sheet of high-quality writing paper with a solution of silver nitrate, drying it, dipping it in a solution of potassium iodide, then drying it again. At this stage, the balance of the chemicals was such that the paper was practically insensitive to light and could be stored indefinitely. When wanted for use, the side initially brushed with silver nitrate was now brushed with a "gallo-nitrate of silver" solution consisting of silver nitrate, acetic acid and gallic acid, then lightly blotted and exposed in the camera. Development was effected by brushing on more of the "gallo-nitrate of silver" solution while gently warming the paper. When development was complete, the calotype was rinsed, blotted, then either stabilized by washing it in a solution of potassium bromide, which converted the remaining silver iodide into silver bromide in a condition such that it would only slightly discolour when exposed to light, or "fixed" in a hot solution of sodium thiosulphate, then known as hyposulphite of soda and commonly called "hypo", which dissolved the silver iodide and allowed it to be entirely washed out, leaving only the silver particles of the developed image and making the calotype completely insensitive to light.

The calotype process produced a translucent original negative image from which multiple positives could be made by simple contact printing. This gave it an important advantage over the daguerreotype process, which produced an opaque original positive that could be duplicated only by copying it with a camera.

Although calotype paper could be used to make positive prints from calotype negatives, Talbot's earlier silver chloride paper, commonly called salted paper, was normally used for that purpose. It was simpler and less expensive, and Talbot himself considered the appearance of salted paper prints to be more attractive. The longer exposure required to make a salted print was at worst a minor inconvenience when making a contact print by sunlight. Calotype negatives were often impregnated with wax to improve their transparency and make the grain of the paper less conspicuous in the prints.

Talbot is sometimes erroneously credited with introducing the principle of latent image development. The bitumen process used in private experiments by Nicéphore Niépce during the 1820s involved the chemical development of a latent image, as did the widely used daguerreotype process introduced to the public by Niépce's partner and successor Louis Daguerre in 1839. Talbot was, however, the first to apply it to a paper-based process and to a negative-positive process, thereby pioneering the various developed-out negative-positive processes which have dominated non-electronic photography up to the present.

Popularity

Despite their flexibility and the ease with which they could be made, calotypes did not displace the daguerreotype.[4] In part, this was the result of Talbot having patented his processes in England and beyond. Unlike Talbot, Daguerre who had been granted a stipend by the French state in exchange for making his process publicly available, did not patent his invention.[4] In Scotland, where the English patent law was not applicable at the time, members of the Edinburgh Calotype Club and other Scottish early photographers successfully adopted the paper-negative photo technology.[5] In England, the Calotype Society was organized in London around 1847 attracting a dozen enthusiasts.[6] In 1853, twelve years after the introduction of paper-negative photography to the public, Talbot's patent restriction was lifted.[7]

In addition, the calotype produced a less clear image than the daguerreotype. The use of paper as a negative meant that the texture and fibers of the paper were visible in prints made from it, leading to an image that was slightly grainy or fuzzy compared to daguerreotypes, which were usually sharp and clear.[4][8] Nevertheless, calotypes—and the salted paper prints that were made from them—remained popular in the United Kingdom and on the European continent outside France in the 1850s, especially among the amateur calotypists, who prized the aesthetics of calotypes and also wanted to differentiate from commercial photographers,[9] until the collodion process enabled both to make glass negatives combining the sharpness of a daguerreotype with the replicability of a calotype later in the nineteenth century. British photographers also brought the calotype to India, where, for example, in 1848, John McCosh, a surgeon in the East India Company, took the first image of the Maharajah Duleep Singh.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "Daguerreotypes – Time Line of the Daguerreian Era – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Hutchins, Laura A.; May, Robert E. (2011). "The Preservation of Finger Ridges". The Finger print Sourcebook (PDF). NIJ and International Association for Identification.

- ↑ US Patent 5171, Henry Fox Talbot: "Improvement in Photographic Pictures" filing date Jun 26, 1847

- 1 2 3 Carlebach, Michael L. (1992). The Origins of Photojournalism in America. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-159-8.

- ↑ Roger Taylor, Guest curator of Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives, 1840–1860, Transcript of the opening speech, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science by Jennifer Tucker, p. 20.

- ↑ Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives, 1840–1860: Exhibition Overview, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ "Photographic Processes: Calotypes (Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. 2011-08-30. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Taylor, Roger, with Larry J. Schaaf. Impressed by light: British photographs from paper negatives, 1840–1860. Accompanies the exhibition 'Impressed by light – British photographs from paper negatives, 1840–1860' held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 24 – December 30, 2007; at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., February 3 – May 4, 2008; and at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, May 26 – September 7, 2008. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.

- ↑ Bance, Peter (2004). The Duleep Singhs: The Photograph Album of Queen Victoria's Maharajah. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 0750934883.

Further reading

- Aronold, H. J. P. William Henry Fox Talbot pioneer of photography and man of science. London: Hutchinson Benham, 1977.

- Baxter, W. R. The Calotype familiarly explained, Photography: including the Daguerreotype, Calotype & Chrysotype. London: H. Renshaw, 1842, 2nd edition.

- Buckland, G. Fox Talbot & the invention of photography. Boston: Gootine, London Scholar Press, 1980.

- Eder, Josef Maria. History of Photography. New York: Dover Publications, 1978. Translated by Edward Epstean.

- Greene, A. Primitive Photography: A Guide to Making Cameras, Lenses, and Calotypes. Focal Press, 2002.

- Lassam, and Seabourne. W H Fox Talbot: Scientist, photographer, classical scholar 1800 – 1877: A further assessment. Lacock, 1977.

- Marshall, F. A. S. Photography: The importance of its applications in preserving pictorial records. Containing a practical description of the Talbotype process. London: Hering & Remington; Peterborough, T. Chadwell & J. Clarke, 1855.

- Meier, Alf B. Basic Photography — a manual for the training of fashion photographers. Frankfurt/M.: Jentzen oHG, 1992.

- Taylor, Roger, with Larry J. Schaaf. Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives, 1840–1860.. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007. Available online, including a biographical dictionary of 500 calotypists.

External links

- The Calotype Society (flickr group)

- All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852–1860, exhibition catalog fully online as PDF from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which contains material on calotype.

- Research database Photographic Exhibitions in Britain, 1839–1865 which contains 1705 records for calotype