Campaspe is an Elizabethan era stage play, a prose comedy by John Lyly based on the story of the love triangle between Campaspe, a Theban captive, the artist Apelles, and Alexander the Great, who commissioned him to paint her portrait. Widely considered Lyly's earliest drama, Campaspe was an influence and a precedent for much that followed in English Renaissance drama, and was, according to F. S. Boas, "the first of the comedies with which John Lyly inaugurated the golden period of the Elizabethan theatre".[1]

Performance and publication

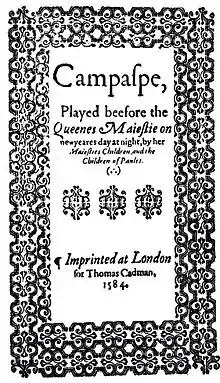

Campaspe was initially acted in the autumn of 1583 at the first Blackfriars Theatre, before being performed at Court at Whitehall Palace before Queen Elizabeth I, most likely on 1 January 1584 (new style). The play was performed, as the first quarto states on its title page, by the Children of the Chapel ("her Maiesties Children") and the Children of Paul's, a combined company also known as Oxford's Boys after its patron the Earl of Oxford, and the name used in Court records. Lyly was in Oxford's service at the time, and was paid £20 for this and for the subsequent Shrove Tuesday Court performance of his Sapho and Phao by a warrant issued on 12 March, although he would have to wait until 25 November to actually receive his money.[2]

Campaspe was first published in quarto in 1584 in three separate editions, printed by Thomas Dawson for the bookseller Thomas Cadman, without any previous entry appearing in the Stationers' Register.[3] Their publication made Lyly the first English writer to see his plays reprinted in a single year.[4] A fourth quarto edition appeared in 1591, printed by Thomas Orwin for William Brome. (Rather than using the terms Q1, Q2, Q3, & Q4 to describe these four quarto editions, some scholars have preferred Q1a, Q1b, Q1c, and Q2.) None of the four name Lyly on their title page. Q1 titles the play A moste excellent Comedie of Alexander, Campaspe, and Diogenes. The three subsequent quartos shorten the title to Campaspe, although in all four the running title (printed along the tops of the text's pages) is given as A tragicall Comedie of Alexander and Campaspe. Editors and scholars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries generally referred to the play as Alexander and Campaspe while their modern counterparts tend to prefer the shorter title. Q1 erroneously states on its title page that it was performed on "twelfe day at night", which Q2 corrects to "newyeares day at night" (a fact confirmed by Court records) and Q3 follows. However Q4, using Q1 as its copy text, reverts to the mistaken day.

.png.webp)

So too does the next edition of the play, printed with its own individual title page in Edward Blount's 1632 collection of Lyly's plays Six Court Comedies, which uses Q4 as its copy text. Blount had entered it into the Stationers' Register on 9 January 1628, naming each play individually under a group entry.[5] This edition not only modernised some of the spelling, but also printed the lyrics of three of the play's four songs for the first time (the last, in Act 5 scene 3, remains missing). Amongst them is the often reprinted Cupid and my Campaspe, sung by the love-struck Apelles at the end of Act 3, in which he describes Cupid gambling away parts of himself:

Cupid and my Campaspe played

At cards for kisses. Cupid paid:

He stakes his quiver, bow and arrows,

His mother's doves and team of sparrows,

Loses them too; then down he throws

The coral of his lips, the rose

Growing on's cheek (but none knows how),

With these the crystal of his brow,

And then the dimple of his chin;

All these did my Campaspe win.

At last he set her both his eyes;

She won, and Cupid blind did rise.

O Love, has she done this to thee?

What shall (alas) become of me?

Some scholars have questioned whether these songs are authentically Lylian in authorship, although according to the play's most recent editor, G. K.Hunter, this "is a hypothesis impossible to disprove; but the evidence that has been adduced to support it is equally without force."[6]

Sources

For his narrative source, Lyly depended on the Natural History of Pliny the Elder for the tale of Alexander the Great and Campaspe. He also drew upon the work of Diogenes Laërtius (the historical biographer) and upon Thomas North's 1580 translation of the Parallel Lives of Plutarch for information about the philosophers of ancient Greece. (The play must therefore have been written between 1580 and 1583.) Lyly derived most of his material for his portrayal of the character of Diogenes (the Cynic philospher) from the translation of Plutarch's Apopththegamata by Erasmus of Rotterdam.[7]

Other individual verbal sources include Plato's Republic, Terence's Eunuchus, Cicero's De natura deorum and In Catilinam, Publilius Syrus's Sententiae, Horace's Ars poetica, Ovid's Ars amatoria, Seneca's De brevitate, Tertullian's Apology, Aelian's Varia historia, and A Short Introduction of Grammar by Lyly's own grandfather, William Lily.[8]

Synopsis

While in Athens, Alexander falls in love with the beautiful Theban captive, Campaspe. He grants the young woman her freedom, and has her portrait painted by the artist Apelles. Apelles quickly falls in love with her too; when the portrait is finished, he deliberately mars it to have more time with his sitter. Campaspe in turn falls in love with Apelles. When Apelles eventually presents the completed portrait to Alexander, the painter's behaviour reveals that he is in love with Campaspe. Alexander magnanimously resigns his interest in Campaspe so that the true love between her and Apelles can flower; he turns his attention to the invasion of Persia and further conquests.

Alexander also spends his time in Athens with his close friend and advisor Hephestion (who disapproves of his infatuation with Campaspe), and in conversing and consorting with the philosophers of the era – most notably with Diogenes the Cynic, whose famous tub is prominently featured onstage. Diogenes is little impressed with the conqueror, although Alexander is with him ("Hephestion, were I not Alexander I would wish to be Diogenes").[9] Plato and Aristotle share a conversation, and four other philosophers from various classical Greek schools, Cleanthes, Crates, Chrysippus, and Anaxarchus (anachronistically drawn from several different centuries) appear as well,[10] all invited into Alexander's presence by his messenger Melippus for debate. An eighth philosopher, Chrysus, another Cynic, begs Alexander for money, but is given short shrift.

The play also features the witty pages that are a hallmark of Lyly's drama, here called Psyllus, Manes, and Granichus, servants to Apelles, Diogenes, and Plato respectively. Additionally, one scene brings on Sylvius and his three performing sons, Perim, Milo, and Trico, who take turns to tumble, dance, and sing. Two Macedonian officers, Clitus and Permenio, both begin the play in bringing on Campaspe and her fellow captive Timoclea, and also appear later to express their concern as Alexander's distracted state leads to a breakdown in military discipline, personified in a further scene where the courtesan Laïs sings (the lyrics remain missing) to entertain two unruly soldiers, Milectus and Phyrgius, as they forget their martial calling ("Down with arms, and up with legs!").[11]

Style

Campaspe's prose style is heavily "euphuistic," sharing significant commonalities with Lyly's famous novel Euphues (1578) in using antitheses, alliterations, repetitions, balanced clauses, and matching parts of speech. Like his Anatomy of Wit, the play is presented mainly as a series of dialogues, soliloquies, and alternating orations.[12] Notably, Apelles is a crucial figure in both works. Lyly expanded his use of dialogue for the play, using short, sharp exchanges for innovative comic and dramatic effect, as shown by this extract from Act 3 Scene 1, where Alexander the Great visits Apelles' studio to check on his progress in painting Campaspe's portrait, and begins to question him about the art of painting:

- Alexander:

Where do you first begin, when you draw any picture?

Apelles:The proportion of the face, in just compass as I can.

Alexander:I would begin with the eye as a light to all the rest.

Apelles:If you will paint as you are, a king, your Majesty may begin where you please; but as you would be a painter, you must begin with the face.

Alexander:Aurelius would in one hour colour four faces.

Apelles:I marvel in half an hour he did not four.

Alexander:Why, is it so easy?

Apelles:No, but he doth it so homely.

Alexander:When will you finish Campaspe?

Apelles:Never finish; for always in absolute beauty there is somewhat above art.

Later on, Alexander borrows Apelles charcoal to try his own hand at drawing:

- Alexander:

Lend me thy pencil, Apelles; I will paint and thou shalt judge.

Apelles:Here.

Alexander:The coal breaks.

Apelles:You lean too hard.

Alexander:Now it blacks not.

Apelles:You lean too soft.

Alexander:This is awry.

Apelles:Your eye goeth not with your hand.

Alexander:Now it is worse.

Apelles:Your hand goeth not with your mind.

- Alexander:

Nay, if all be too hard or soft, so many rules and regards that one’s hand, one’s eye, one’s mind must all draw together, I had rather be setting of a battle than blotting of a board. But how have I done here?

Apelles:Like a king.

Alexander:I think so; but nothing more unlike a painter.

Influence

Campaspe marked a significant turning point in English drama. According to Frederick Kiefer, Lyly's prose style "created a form of dramatic speech unprecedented in the theater",[13] and, as J. F MacDonald observed, is the moment when the "real movement towards prose in the drama begins."[14] With Campaspe, according to Jonas Barish, “Lyly invented, virtually single-handed, a viable comic prose for the English stage”[15]

Lyly provides no moral or ethical lesson in his Campaspe — thereby breaking away from the morality play tradition of earlier drama. And unlike most of his subsequent plays, Campaspe eschews allegory as well. Instead, Campaspe delivers a romantic historical tale purely for its entertainment value. His departure from the Medieval mindset provided a model for later writers to follow. The play has been called "the first romantic drama" of its era.[16]

Thomas Nashe quotes from Campaspe in his play Summer's Last Will and Testament (1592).

Modern publication and performance history

The play was printed in R. W. Bond's The Complete Works of John Lyly (Oxford, 1902; vol ii, pp. 302-60; reprinted 1967), still the only complete collected works of Lyly ever published. Joseph Quincy Adams printed the play as part of his Chief Pre-Shakespearean Dramas in 1924 (London; pp. 609-35.) The Malone Society published their reprint of the play, overseen by W.W. Greg (No. 75; Oxford, 1934 for 1933). Daniel A. Carter published the play as part of his collected Plays of John Lyly in 1988 (Lewisburg, London, and Toronto). The most recent modern edition remains the 1991 Revels Plays edition (Manchester University Press), edited by G. K. Hunter (published in a single volume along with Sapho and Phao, edited by David Bevington).

The play seems to have been revived in an adapted and cut down version retitled The Cynic or the Force of Virtue, performed twice, 22-3 February 1732, at Odell's Theatre in Aycliffe Street in Goodman's Fields. Henry Giffard, the theatre's manager, played Apelles, his wife played Campaspe, and his brother played Alexander, with the veteran actor Philip Huddy taking on the role of Diogenes.[17]

In 1908, students from Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford performed in an all-female, Elizabethan dress production in the city's New Masonic Hall, on 7, 8, and 9 December, directed by Miss Hadow, in aid of the college library.[18]

The first modern performance by professional actors of the uncut play took place on 27 October 2000 at The Bear Gardens theatre, London, for Shakespeare's Globe's Read Not Dead project, with Eve Best and Will Keen as Campaspe and Apelles, Tom Espiner as Alexander, and Dominic Rowan as Diogenes. Angus Wright played Clitus and Nicholas Rowe played Parmenio. Duncan Wisbey composed original music for the four songs, and also played Psyllus, alongside Roddy McDevitt as Granichus and Alan Cox as Manes. The performance was directed by James Wallace, and was recorded on digital audio for the Globe's archives.[19]

References

- ↑ Frederick S. Boas An Introduction to Tudor Drama, Oxford University Press, 1933; p. 83.

- ↑ Martin Wiggins British Drama 1533-1642: A Catalogue, Oxford University Press, 2012; Volume II: 1567-1589, pp. 322-4.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; pp. 1-2.

- ↑ Andy Kesson John Lyly and early modern authorship, The Revels Plays Companion Library, Manchester University Press, 2014; p. 145.

- ↑ Martin Wiggins British Drama 1533-1642: A Catalogue, Oxford University Press, 2012; Volume II: 1567-1589, p. 324.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; p. 301.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; p. 10.

- ↑ Martin Wiggins British Drama 1533-1642: A Catalogue, Oxford University Press, 2012; Volume II: 1567-1589, p. 323.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; Act 2 Scene 2, lines 167-8, p. 84.).

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; p. 14.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; Act 5 Scene 4, line 3, p. 124.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; p. 24.

- ↑ Frederick Kiefer John Lyly and the Most Misread Speech in Shakespeare, Connotations - A Journal for Critical Debate, Vol. 28, 2019; p. 32.

- ↑ J. F. MacDonald The Use of Prose in English Drama before Shakespeare, University of Toronto Quarterly, Vol 2.4, July 1933; pp. 465-81.

- ↑ Jonas A. Barish The Prose Style of John Lyly, English Literary History, Vol 23.1, March 1956; pp. 14-35.

- ↑ John Dover Wilson, John Lyly, Cambridge, Macmillan and Bowes, 1905; p. 100.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; p. 38.

- ↑ George K. Hunter and David Bevington Campaspe and Sappho and Phao, The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1991; p. 39.

- ↑ Play programme "Campaspe". Shakespeare's Globe Read Not Dead archive. read-not-dead.quartexcollections.com. 2000. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

External links

- Q1 original spelling play text online at Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership with the University of Michigan

- Modern spelling play text online at elizabethandrama.org