Canton Viaduct | |

|---|---|

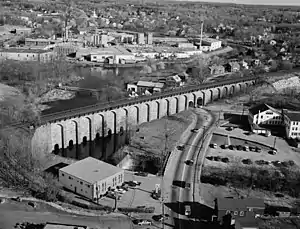

A west side view of the Canton Viaduct looking south with the former Paul Revere Copper Rolling Mill in the background, April 1977 | |

| Coordinates | 42°09′32″N 71°09′14″W / 42.15889°N 71.15389°W |

| Carries | 2 tracks (standard gauge) presently serving:

|

| Crosses |

|

| Locale | Canton, Massachusetts |

| Other name(s) | Great Stone Bridge, Viaduct at Canton |

| Maintained by | Amtrak owned by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) |

| Heritage status | |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Blind arcade cavity wall |

| Material |

|

| Total length | 615' |

| Width | 26'-28' (foundations), 22'-24' walls |

| Height | 60' above river level, 70' maximum height |

| Longest span | 2 at 28' (granite/concrete deck arches over the granite roadway portal) |

| No. of spans | 71 total |

| Piers in water | 7 (15 on land) |

| Clearance above | Approximately 21' |

| History | |

| Designer | William Gibbs McNeill, Chief Engineer for the Boston & Providence Railroad (B&P) |

| Construction start | April 20, 1834 |

| Opened | July 28, 1835 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 106 trains per day |

Canton Viaduct | |

| Location | Neponset and Walpole Sts., Canton, Massachusetts |

| Built | 1834 |

| Architect | McNeill, William Gibbs; Dodd & Baldwin |

| NRHP reference No. | 84002870[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 20, 1984 |

| Location | |

Canton Viaduct is a blind arcade cavity wall in Canton, Massachusetts, built in 1834–35 for the Boston and Providence Railroad.[2]

At its completion, it was the longest (615 ft [187 m]) and tallest (70 ft [21 m]) railroad viaduct in the world; today, it is the last surviving viaduct of its kind. It has been in continuous service for 188 years; it now carries high-speed passenger and freight rail service. It supports a train deck about 65 feet (20 m) above the Canton River that passes through six semi-circular portals.

The Canton Viaduct was the final link built for the B&P's then 41-mile (66 km) mainline between Boston, Massachusetts and Providence, Rhode Island.[3] Today, the viaduct serves Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, as well as Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) Providence/Stoughton Line commuter trains. It is located 0.3 miles (0.5 km) south of Canton Junction, at milepost 213.74 (at the north end of the viaduct) reckoned from Pennsylvania Station in New York City, and at the MBTA's milepost 15.35, reckoned from South Station in Boston.

Inception

The Canton Viaduct was erected in 1835 by the Boston and Providence Railroad shortly after its founding in 1831. It was designed by William Gibbs McNeill, a Captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and West Point graduate. He was assisted by engineers, George Washington Whistler (McNeill's brother-in-law), Isaac Ridgeway Trimble and William Raymond Lee. McNeill and Whistler were the uncle and father of the artist James McNeill Whistler. The viaduct was built by Dodd & Baldwin[4] from Pennsylvania; the firm was established by cousins Ira Dodd and Caleb Dodd Baldwin. Around this time, Russia was interested in building railroads. Tsar Nicholas I sent workmen to draw extensive diagrams of the Canton Viaduct. He later summoned Whistler to Russia as a consulting engineer to design the Moscow–Saint Petersburg Railway, on which two viaducts were modeled after the Canton Viaduct. A scale model viaduct of similar design is on display at the Oktyabrsky Railroad Museum in St. Petersburg.

Design and construction

Classification

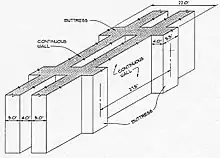

This Canton Viaduct is the only known structure using blind arcades in combination with a cavity wall to form a hollow bridge. Although the deck arches appear to extend through to the other side, they do not; each deck arch is only four feet deep. The deck arches support the spandrels, deck (extending beyond the walls), coping and parapets; they are adjacent to the longitudinal walls. The only arches extending through the viaduct to the other side are six river portals and two roadway portals. The 20 'buttresses' are also unique in that they extend through to the other side, so they are actually transverse walls.

Materials

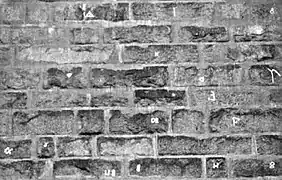

The Canton Viaduct contained 14,483 cubic feet (15,800 perches) of granite, which weighs approximately 66,000,000 pounds (33,000 short tons) prior to its concrete redecking in 1993. Each stone has a Mason's mark to identify who cut the stone. Each course is 22" - 24" high and laid in a pattern closely resembling a Flemish bond. Exterior stone for the walls, wing wall abutments, portals, deck arches, coping, parapets and the foundation stone are riebeckite granite[5] mined from Moyles quarry (a.k.a. Canton Viaduct Quarry) located on the westerly slope of Rattlesnake Hill in Sharon, Massachusetts; now part of Borderland State Park.

Location

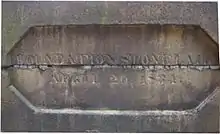

The majority of the viaduct is over land (71%), while 29% is over water. In addition to the six river portals, one roadway portal was originally provided. The distance between the transverse walls at this section is wider than all the other sections of the viaduct. The overall length is 615 feet (187 m) with a one degree horizontal curve that creates two concentric arcs. This makes the west wall slightly shorter than the east wall producing a slight keystone shape in the cavities. Originally unnamed, it was referred to as "the great stone bridge" and "the viaduct at Canton" before it was eventually named after the town. The foundation stone was laid on Sunday, April 20, 1834 in the northeast corner with a Masonic Builders' rites ceremony.

Construction

The Canton Viaduct cost $93,000 to build ($2,638,200 today[6]). Construction took 15 months, 8 days from laying of the foundation stone on April 20, 1834, to completion on July 28, 1835.

The transverse walls are 5 feet, 6 inches wide. The wing wall abutments are 25 feet wide where they meet the viaduct; they are curved and stepped and were excavated by William Otis using his first steam shovel. From the top of the wing walls to midway down, the stones are of 2' wide; from midway down to the bottom of the wing walls the stones are 4' wide. The west wing walls served as staircases for passengers to ascend and descend while the viaduct was being constructed. These wing wall stones have holes drilled in them where railings were attached.

The coping is supported by 42 segmental deck arches (21 on each side) that span the tops of 20 transverse walls beyond the longitudinal walls. The longitudinal walls are five feet thick with a four-foot gap between them joined with occasional tie stones. More construction details are available in the original . When the viaduct had a single set of tracks, the rails were placed directly over the longitudinal walls as the cavity's width is less than standard gauge. When the viaduct was double tracked in 1860, the inside rails were placed directly over the longitudinal walls and the outside rails were supported by the deck arches.

The viaduct was "substantially complete" in June 1835 from various accounts of horse-drawn cars passing over it during that time. The viaduct was built before the advent of construction safety equipment such as hard hats and fall arrest devices. Surprisingly, no deaths were recorded during the construction, but deaths have occurred at the viaduct since completion; mainly from people crossing it while trains passed in opposite directions. Charlie, the old white horse who had hauled the empty railcars back to Sharon, Massachusetts (4 miles), was placed upon a flat car and hauled across the viaduct by the workers, thus becoming the first "passenger" to cross the structure.

A June 6, 1835, article in the Providence Journal describes it. As reported by the Boston Advertiser and the Providence Journal, "Whistler" was the first engine to pass over the entire length of the road.

An iron parapet was placed on the viaduct in 1878.[7]

Aside from seasonal vegetation control and occasional graffiti removal, the viaduct requires no regular maintenance other than periodic bridge inspections from Amtrak.

Dedication Stone

The dedication stone's capstone, in the south end of the west parapet was the last stone to be laid in the viaduct.

The Dedication Stone is actually two stones now held together with two iron straps on each end. The overall dimensions are approximately 60" long × 36" high × 18" wide, and it weighs approximately 3,780 lbs. The Dedication Stone was originally topped with a 63" long × 8" high × 24" wide capstone with double beveled edges, creating an irregular hexagonal profile. Due to its breaking in 1860, the Dedication Stone is about 1" shorter today than its original height. The damage obscured two directors' names, W. W. Woolsey and P. T. Jackson. Woolsey was also a Director of the Boston & Providence Railroad & Transportation Co. (B&P RR&T Co. Archived 2008-05-11 at the Wayback Machine) in Rhode Island (incorporated May 10, 1834) which owned the Rhode Island portion of the Boston and Providence rail line. The B&P RR&T Co. merged with the B&P on June 1, 1853.

Railroad track

During the 1993 deck renovation, two 18-inch-deep troughs were discovered recessed into the granite deck stones running the entire length of the viaduct and spaced at standard gauge width (56+1⁄2 inches). The troughs contained longitudinal baulks and were part of the original construction. The baulks supported the rails without the need for transoms as the gauge was maintained by the longitudinal troughs. This is the only known instance of transomless baulks recessed in granite slabs; the original tracks before and after the viaduct used baulks making the B&P originally a baulk railroad. A 1910 photo taken atop the viaduct shows dirt between the cross ties and tracks, so this material may have been used before traditional gravel ballast.

Baulks were used to support strap rails or bridge rail. These early rails would have been replaced with flanged T-rails by 1840. These photos[8] show baulks at Canton Junction in 1871. An 1829 report from the Massachusetts Board of Directors of Internal Improvements describes how the railroad from Boston to Providence was to be built. The report states, "It consists of one pair of tracks composed of long blocks of granite, about one foot square, resting upon a foundation wall extending to the depth of 2+1⁄2' below the surface of the ground, and 2' wide at the bottom". The report also calls for using horse-drawn wagons and carriages at 3 MPH on the rail line, not steam locomotives.

Construction sequence

The Canton Viaduct was constructed in the following sequence:

- Planning

- Requirements, design and specifications

- Preconstruction

- Site preparation, mobilization, surveying, excavation, river diversion (using cofferdams)

- Construction

- Wing wall abutment foundations and walls

- Temporary train platforms and wing wall abutment staircases

- Walls:

- Foundations

- Longitudinal walls with river portals and vehicle portal (using falsework) and transverse walls

- Deck arches and spandrels

- Cavity slabs and deck slabs (with longitudinal troughs) and coping

- Parapets with dedication stone

- Post Construction

- Track installation - baulks, rail and ballast

- Removal of temporary train platforms and wing wall abutment staircases

- Site cleanup and demobilization

Waterway

Spillway Dam at Neponset Street, also known as Canton Viaduct Falls, impounds Mill Pond. It is a weir or low head dam that is owned by the MBTA. The 16' high by 90' long granite dam was built in 1900; as of 2009, it averages 78 cu ft/s (2.2 m3/s) annual discharge.[9] Water power was supplied to nearby businesses via water wheel from the canal starting at the waterfall and continuing about 200' under the Neponset St. bridge. There were also two channels located between the viaduct and the waterfall (one on each side) referred to as sluices, headraces and flumes in various maps. They were filled in sometime after 1937 (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers National Inventory of Dams No. MA03106).

Ownership

- 1834–1888, Boston & Providence Railroad Corp.

- 1888–1893, Old Colony Railroad Co.

- 1893–1969, New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad Co.

- 1969–1973, Penn Central Transportation Company

- 1973–present, Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

Critical infrastructure

- World War I - A detachment of the 9th Regiment National Guard arrived in April 1917 to guard the viaduct from sabotage, via sentry duty.

- World War II - Canton's Civil Defense Corps and railroad employees guarded the viaduct against sabotage since the train line is part of the direct link between Boston and New York City. The structure is a critical transportation link between the two cities and had extra protection as a result.

- War on Terrorism - Shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 the Canton Viaduct was guarded by various security entities until the U.S. threat level decreased.

In a letter to Canton's Board of Selectmen on February 27, 2002, former Police Chief Peter Bright noted that Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency training for worst-case situations highlights the destruction of the Canton Viaduct for its disruption of the national railroad system; the Federal Government also considers the viaduct a high-risk target.[10]

Recognition

- The Canton Viaduct was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.[11]

- The viaduct has been designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1998 by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Current status

In June 2004 the town of Canton developed a Master Plan[12] that identifies what should be preserved and enhanced to meet evolving needs and improve the quality of life.

Gallery

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ "National Register Information System – (#84002870)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ↑ Hall, Candace (July 22, 2010). "Canton Viaduct: 175 and still chugging along". Canton Journal.

- ↑ Not the current distance, due to later route changes.

- ↑ "MASSACHUSETTS - Norfolk County". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ↑ Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (2013-04-05). "Nature and Science". Borderlands Park. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

- ↑ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ↑ Report of the Board of Directors of the Boston and Providence Railroad Corporation for the Year Ending September 30, 1878. Boston and Providence Railroad. 1878. p. 8.

- ↑ Canton Historical Society: Canton Junction

- ↑ "USGS Surface Water data for USA: USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics".

- ↑ Former Canton Police Chief Bright's letter is public record, available at the Canton Police Department and Canton's Board of Selectmen. Archived 2009-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Planning Department". Archived from the original on 13 March 2010.

Further reading

- Galvin, Edward, D. (1987). A History Of Canton Junction. Brunswick: Sculpin Publications.

- Fisher, Charles, E. (1917). A Little Story Of The Boston And Providence Railroad Company.

- Herrin, Dean, A. (2002). America Transformed: Engineering And Technology In The Nineteenth Century: Selections From The Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service. Reston: American Society of Civil Engineers. ISBN 978-0-7844-0529-1

- Cook, Richard, J. (1987). The Beauty Of Railroad Bridges: In North America - Then And Now. San Marino: Golden West Books. ISBN 978-0-87095-097-1

- Cleary, Richard, L. (2007). Bridges. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-73136-1

- Cramb, Ian. (2006), The Art Of The Stone Mason. Chambersburg: Hood & Co. ISBN 978-0-911469-27-1

- Canton Bicentennial Historical Committee. (1997), Canton Comes Of Age 1797–1997: A History Of The Town Of Canton, Massachusetts. Canton: The Town of Canton

- Comeau, George, T. (2009). Canton - Postcard History Series. Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7203-1

- Cox, Terry. (2003). Collectible Stocks And Bonds From North American Railroads: Guide With Prices. Arvada: TCox & Associates. ISBN 978-0-9746485-0-7

- Boothroy, Stephen, J. (2002). Down At The Station: Rail Lines Of Southern New England In Early Postcards. Cranberry Junction. ISBN 978-0-9714961-4-9

- Jackson, Donald, C. (1988). Great American Bridges And Dams. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-14385-7

- Barber, John, W. (1844). Historical Collections, Being A General Collection Of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, etc., Relating To The History And Antiquities Of Every Town In Massachusetts, With Geographical Descriptions, Illustrated By 200 Engravings. Heritage Books. ISBN 978-1-55613-463-0

- DeLony, Eric. (1993). Landmark American Bridges. Little Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-8212-2036-8

- Middleton, William, D. (1999). Landmarks On The Iron Road: Two Centuries OF North American Railroad Engineering. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33559-3

- Kirkland, Edward C. (1948). Men, Cities And Transportation - A Study In New England History 1820–1900 Volumes I-II. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- National Park Service. (1995). National Register Of Historic Places 1966 To 1994. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-14403-8

- Solomon, Brian. (2008). North American Railroad Bridges. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2527-8

- Adams, Charles, F. (1878). Railroads: Their Origin And Problems. Ayer Co. Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-13764-8

- Harlow, Alvin, F. (1946). Steelways Of New England. New York: Creative Age Press, Inc. *Rogers, Robert. (1952).

- Middleton, William D. "They're Still There: High Speed Rail's 1835 Underpinning," American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Spring 2001 Volume 16, Issue 4, pp 52–55

- Parry, Albert. (1938). Whistler's Father. Foster Press. ISBN 978-1-4067-7594-5