Capo Colonna

Promunturium Lacinium | |

|---|---|

The last column of the Temple dedicated to Hera (Juno) Lacinia. | |

Capo Colonna Location in Italy | |

| Coordinates: 39°01′46″N 17°12′18″E / 39.02944°N 17.20500°E | |

| Location | Calabria, Italy |

| Offshore water bodies | Ionian Sea |

.png.webp)

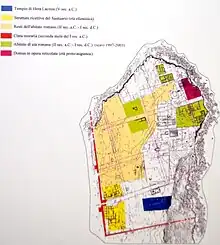

Capo Colonna (sometimes Capo Colonne or Capo della Colonne) is a cape in Calabria located near Crotone. In ancient Roman times the promontory was called Promunturium Lacinium (Ancient Greek: Λακίνιον ἄκρον).[1] The modern name derives from the remaining column of the Temple of Hera Lacinia.

The peninsula was the site of a great sanctuary of Hera from the 7th c. BC, the most famous in Magna Graecia.

Later the Romans built the fortified town of Lacinium over the area.

The entire peninsula is now within the Capo Colonna Archaeological Park and a museum nearby houses important finds.

Excavations from 2014 have greatly increased knowledge of the site.

History

The Cape became an ancient Greek sanctuary to Hera in the 7th c. BC and one of the most important sanctuaries of Magna Graecia.[2] It was closely linked to the ancient Greek colony of Kroton nearby.

The Roman colony of Lacinium

In 194 BC after the Second Punic War the Romans created a maritime colony here, entrusted to the triumvirs Cn. Octavius, L. Aemilius Paulus, C. Laetorius.[3] The occupation was not limited to the settlement at Capo Lacinio as excavations have shown that the agricultural hinterland was occupied by at least 91 rural farms of various sizes and periods, presumably on land distributed to the settlers after 194 BC, and with occupation continuing to the late empire.[4] Colonies usually received 300 men, generally veterans, each who would be assigned from 1 to 2.5 hectares of agricultural land from the ager colonicus (state land), as well as free use of the ager compascus scripturarius (common state land) for pasture and woodland.[5] With their families, around 1500 Roman citizens in total can be assumed.

The maritime role of the colony of Lacinium was highlighted as early as 190 BC when Livy, as prefect of the Roman fleet, inspected the ships coming from the Tyrrhenian and Ionian seas there before they set off towards the Aegean against Antiochus III.[6]

The settlement eventually occupied the entire northern end of the promontory and was organised with a rectangular street plan with three main streets oriented east-weast and avoiding the Sanctuary of Hera and its immediate surroundings on a different alignment.

From the second half of the 2nd century BC, town house construction increased which occupied a good part of the sectors between the central plateau and the northern edge of the cliff. Near the NE cliff two houses belonging to rich local people arose from the end of the 2nd century BC. The domus "DR" is the oldest (end of the 2nd century BC, of about 15 x 34 m) and had a residential part around the atrium and a sector for service and production which overlooked a courtyard. The tablinum has a mosaic floor with animals (ducks, dolphins, fish).[7]

The baths were originally built for another public function (the first two phases are in opus quadratum and opus implectum). Between the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 1st century BC the building was remodeled and enlarged in opus incertum to create a bath complex or balneum (III phase, Sullan era), by the duumvirs Lucilius Macer and Annaeus Trasus in 80-70 BC, as attested by an inscription on the mosaic. A circular sweating room (laconicum) and a furnace (praefurnium) were built to heat the water for the hot bath (solium) in a large room on whose floor is a mosaic with geometric motifs (meandering 3D polychrome swastikas, a wave motif) framing a central rhomboidal checkerboard with four dolphins at the corners.

The later domus "CRr" (last 30 years of the 1st century BC) is exceptional both for its building techniques and its area of over 2100 m2. The entrance portico provided a sheltered public area for shops including a room for the sale of drinks (a caupona) with a serving counter in calcarenite. The domus was entered via a large atrium, in the first phase Tuscan (i.e. without columns), and then tetrastyle (i.e. with four columns supporting the roof to collect rainwater). After abandonment and ruin at the beginning of the 2nd century AD, some of its rooms were rebuilt between the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd century with a pottery kiln for terracotta artefacts.

The defensive walls in opus reticulatum with a rectanglar plan were reconstructed probably after the pirate raids of the second and third quarter of the 1st century BC and after the siege of Sextus Pompeius in 36 BC.[8] The sanctuary was renovated soon afterwards, as shown by tile stamps.[9]

A public L-shaped portico forming a public square or forum, aligned with the adjacent domus, is from the Augustan age. A major complex with an imposing monumental fountain near the sanctuary also dates from the late 1st century BC lasting until the 3rd/4th century AD.

The decline and progressive abandonment of the town of Lacinium probably began after the Augustan era. The settlement became a mansio or statio marked as "Licenium" on the Peutinger Map, and more and more concentrated around the sanctuary.

Even after the abandonment of the town, the continuation of devotion to Hera Lacinia is still attested between 98 and 105 AD from an altar dedicated by Oecius imperial procurator (libertus procurator), in favour of Ulpia Marciana, sister of Trajan.

Sights

Sanctuary of Hera Lacinia

The ruins of an Ancient Greek temple dedicated to Hera (Juno) are visible on the cape. The temple was said to have still been fairly complete in the 16th century, but was destroyed to build the episcopal palace at Crotone. The remaining feature is a Doric column with capital, about 27 feet (8.2 m) in height.

See also

References

- ↑ Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Lacinium

- ↑ William Smith, CROTON or CROTONA, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854) https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0064:entry=croton-geo&toc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0064%3Aalphabetic+letter%3DS%3Aentry+group%3D12

- ↑ Livy Book XXXIV; 45

- ↑ FAUSTO ZEVI, Kroton. Studi e ricerche sulla polis achea e il suo territorio (Atti e Memorie della Società Magna Grecia, s. IV, vol. V, 2011-2013) a cura di Roberto Spadea, Roma, Giorgio Bretschneider Editore, 2014

- ↑ C.G.Severino, Crotone. Da polis a città di Calabria, 1988, p. 29

- ↑ Livy,XXXVI, 42, 1-4

- ↑ Giuseppe Celsi, La colonia romana di Croto e la statio di Lacenium, Gruppo Archeologico Krotoniate (GAK) https://www.gruppoarcheologicokr.it/la-colonia-romana-di-croto/

- ↑ Salvatore Medaglia, Carta archeologica della provincia di Crotone, Università della Calabria 2010 ISBN 978-88-903625-4-5

- ↑ Clara Stevanato, Senators and memory in the funerary epigraphy of Roman Italy (1st century BC-3rd century AD), 2020, p. 95

Bibliography

- See R. Koldewey and O. Puchstein, Die griechischen Tempel in Unteritalien und Sicilien (Berlin 1899, 41).

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lacinium, Promunturium". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 50.