| Capture of Klisura Pass | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Italian War | |||||||

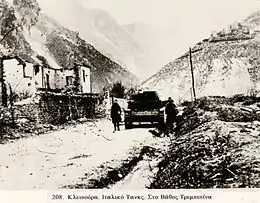

Greek soldiers next to a captured Italian tank | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 300 killed & 350 captured (including 25 officers)[1] | Unknown | ||||||

The Capture of Klisura Pass (Greek: Κατάληψη της Κλεισούρας) was a military operation that took place during 6–11 January 1941 in southern Albania, and was one of the most important battles of the Greco-Italian War. The Italian Army, initially deployed on the Greek-Albanian border, launched a major offensive against Greece on 28 October 1940. After a two-week conflict, Greece managed to repel the invading Italians in the battles of Pindus and Elaia–Kalamas. Beginning on 9 November, the Greek forces launched a major counteroffensive and penetrated deep into Italian-held Albanian territory. The Greek operations culminated with the capture of the strategically important Klisura Pass in January 1941.[2]

Background

After its successful counter-attack and the Battle of Morava–Ivan, the Hellenic Army penetrated deep into Italian-held Albanian territory, taking control of the local urban centers of Gjirokastër and Korçë by December 1940. In a war council on 5 December, General Alexander Papagos, worried about the possibility of German intervention in support of the Italians, attempted to hasten the advance. Moreover, Generals Pitsikas and Tsolakoglou suggested the immediate capture of the Klisura Pass so as to secure the Greek positions.[3]

During the period of the Greek counter-offensive, the Greek forces had much greater distances to contend with and their logistics and road network were substantially inferior compared to the Italians. The Klisura Pass was a particularly strategic location near the town of Berat and the topography of the terrain in addition to bad weather made the operation extremely difficult.[4]

Battle

The attack was led by the II Army Corps, and especially by the 1st and 11th divisions.[5] During the battle, the Italians used for the first time the new M13 medium tanks of the Centauro Armored Division. They were used in frontal attacks, but were decimated by Greek artillery fire.[6] On 10 January, after four days of fierce battles, the Greek infantry divisions finally captured the pass. The final assault that resulted in the location's capture was led by the recently arrived 5th Division, which consisted mainly of Cretans.[4][7]

The Italian headquarters immediately launched counterattacks to recapture the sector. Italian Supreme Commander Ugo Cavallero ordered the newly arrived Lupi di Toscana Division to support the Julia Alpine Division, but the operation was ill-prepared. Although they faced only four Greek battalions, they rapidly lost one battalion of their own due to encirclement. By 11 January, the Italian attack had been pushed back and over the next days, the Lupi di Toscana were almost annihilated. This failure secured Greek possession of the pass.[8]

Aftermath

The capture of the strategic pass by the Greek army was considered a major success by the Allied forces, with the Commander of the British forces in the Middle East, Archibald Wavell, sending a congratulatory message to Alexander Papagos.[9]

In the following weeks, the front lines stabilized, with the Greek forces facing a bad logistical situation and the Italians managing to gain numerical superiority in order to stop their retreat. Both sides kept their positions until the German intervention in April 1941.[10]

On January 22, 2018, following an agreement between the Greek and Albanian foreign ministers, a systematic effort to recover the bodies of fallen Greek soldiers from the battle was undertaken between the two countries.[11][12][13] The remains of the Greek soldiers will be buried in the Greek military cemetery located within the pass.[13]

References

- ↑ Ιωάννης Παπαφλωράτος, Η Ιστορία της Α' μεραρχίας πεζικού, περιοδικό Στρατιωτική Ιστορία, τ. 129, Μάιος 1997, (page. 10)

- ↑ "Balkan studies: biannual publication of the Institute for Balkan Studies". Balkan Studies. 33: 116. 1990.

- ↑ Sakellariou, M. V. (1997), Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization, Ekdotike Athenon, p. 392, ISBN 978-960-213-371-2

- 1 2 Hunt, David (1990). A don at war: Cass Series on Politics and Military Affairs in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7146-3383-1.

- ↑ Army History Directorate (Greece). An abridged history of the Greek-Italian and Greek-German war, 1940–1941. Hellenic Army General Staff, 1997. ISBN 978-960-7897-01-5, p. 128

- ↑ Sweet, John Joseph Timothy (1990). Iron Arm: The Mechanization of Mussolini's Army, 1920–1940. Stackpole Books. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8117-3351-9.

- ↑ Sir Hunt, David (1995). Greece in the Second World War. Ball State University. p. 23.

- ↑ MacGregor, Knox (1986). Mussolini unleashed, 1939–1941: politics and strategy in fascist Italy's last war. Cambridge University Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-0-521-33835-6.

- ↑ Hadjipateras C.N.; Chatzēpateras Kōstas N.; Fafalios M.S.; Phaphaliou Maria S. (1996). Greece 1940–41 eyewitnessed. Efstathiadis Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-960-226-533-8.

- ↑ Cervi, Mario (1972). The Hollow Legions. London: Chatto and Windus. pp. 309, 320. ISBN 0-7011-1351-0.

- ↑ "MFA welcomes measures to disinter, identify fallen Greek soldiers in Albania". ekathimerini.

- ↑ "Ιστορική στιγμή: Ξεκίνησε η εκταφή των Ελλήνων πεσόντων του '40 στο μέτωπο της Αλβανίας". 22 January 2018.

- 1 2 "Αρχίζει η εκταφή των Ελλήνων στρατιωτών πεσόντων στα βουνά της Αλβανίας". 21 January 2018.