| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Dichlorodi(fluoro)methane | |||

| Other names

Dichlorodifluoromethane Carbon dichloride difluoride Dichloro-difluoro-methane Difluorodichloromethane Freon 12 R-12 CFC-12 P-12 Propellant 12 Halon 122 Arcton 6 Arcton 12 E940 Fluorocarbon 12 Genetron 12 Refrigerant 12 | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.813 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E940 (glazing agents, ...) | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1028 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| CCl2F2 | |||

| Molar mass | 120.91 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless Gas | ||

| Odor | ether-like at very high concentrations | ||

| Density | 1.486 g/cm3 (−29.8 °C (−21.6 °F)) | ||

| Melting point | −157.7 °C (−251.9 °F; 115.5 K) | ||

| Boiling point | −29.8 °C (−21.6 °F; 243.3 K) | ||

| 0.286 g/L at 20 °C (68 °F) | |||

| Solubility in alcohol, ether, benzene, acetic acid | Soluble | ||

| log P | 2.16 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 568 kPa (20 °C (68 °F)) | ||

Henry's law constant (kH) |

0.0025 mol kg−1 bar−1 | ||

| −52.2·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.0097 W/(m·K) (300 K)[1] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Tetrahedral | |||

| 0.51 D[2] | |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Warning | |||

| H280, H336, H420 | |||

| P261, P271, P304+P340, P319, P403+P233, P405, P410+P403, P501, P502 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable[3] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LC50 (median concentration) |

760,000 ppm (mouse, 30 min) 800,000 ppm (rabbit, 30 min) 800,000 ppm (guinea pig, 30 min) 600,000 ppm (rat, 2 h)[4] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 1000 ppm (4950 mg/m3)[3] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1000 ppm (4950 mg/m3)[3] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

15000 ppm[3] | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Dichlorodifluoromethane (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

Dichlorodifluoromethane (R-12) is a colorless gas usually sold under the brand name Freon-12, and a chlorofluorocarbon halomethane (CFC) used as a refrigerant and aerosol spray propellant. In compliance with the Montreal Protocol, its manufacture was banned in developed countries (non-article 5 countries) in 1996, and in developing countries (Article 5 countries) in 2010 out of concerns about its damaging effect on the ozone layer.[5] Its only allowed usage is as a fire retardant in submarines and aircraft. It is soluble in many organic solvents. R-12 cylinders are colored white.

Preparation

It can be prepared by reacting carbon tetrachloride with hydrogen fluoride in the presence of a catalytic amount of antimony pentachloride:

- CCl4 + 2HF → CCl2F2 + 2HCl

This reaction can also produce trichlorofluoromethane (CCl3F), chlorotrifluoromethane (CClF3) and tetrafluoromethane (CF4).[6]

History

Charles Kettering, vice president of General Motors Research Corporation, was seeking a refrigerant replacement that would be colorless, odorless, tasteless, nontoxic, and nonflammable. He assembled a team that included Thomas Midgley, Jr., Albert Leon Henne, and Robert McNary. From 1930 to 1935, they developed dichlorodifluoromethane (CCl2F2 or R12), trichlorofluoromethane (CCl3F or R11), chlorodifluoromethane (CHClF2 or R22), trichlorotrifluoroethane (CCl2FCClF2 or R113), and dichlorotetrafluoroethane (CClF2CClF2 or R114), through Kinetic Chemicals which was a joint venture between DuPont and General Motors.[7]

Use as an aerosol

The use of chlorofluorocarbons as aerosols in medicine, such as USP-approved salbutamol, has been phased out by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. A different propellant known as hydrofluoroalkane, or HFA, which was not known to harm the environment, was chosen to replace it.[8]

Retrofitting

R-12 was used in most refrigeration and vehicle air conditioning applications prior to 1994 before being replaced by 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane (R-134a), which has an insignificant ozone depletion potential. Automobile manufacturers started using R-134a instead of R-12 in 1992–1994. When older units leak or require repair involving removal of the refrigerant, retrofitment to a refrigerant other than R-12 (most commonly R-134a which has a global warming potential 3,400 times that of carbon dioxide) is required in some jurisdictions. The United States does not require automobile owners to retrofit their systems; however, taxes on ozone-depleting chemicals coupled with the relative scarcity of the original refrigerants on the open market make retrofitting the only economical option. Retrofitment requires a system flush and a new filter/dryer or accumulator, and may also involve the installation of new seals and/or hoses made of materials compatible with the refrigerant being installed. Mineral oil used with R-12 is not compatible with R-134a. Some oils designed for conversion to R-134a are advertised as compatible with residual R-12 mineral oil. Another replacement for R-12 is the highly flammable, but truly drop-in HC-12a, whose flammability has led to injuries and deaths in a bus fire in 2006.[9][10]

Dangers

Aside from its environmental impacts, R12, like most chlorofluoroalkanes, forms phosgene gas when exposed to a naked flame.[11]

Properties

Table of thermal and physical properties of saturated liquid refrigerant 12:[12][13]

| Temperature (°C) | Density (kg/m^3) | Specific heat (kJ/kg K) | Kinematic viscosity (m^2/s) | Conductivity (W/m K) | Thermal diffusivity (m^2/s) | Prandtl Number | Bulk modulus (K^-1) |

| -50 | 1546.75 | 0.875 | 3.10E-07 | 0.067 | 5.01E-01 | 6.2 | 2.63E-03 |

| -40 | 1518.71 | 0.8847 | 2.79E-07 | 0.069 | 5.14E-01 | 5.4 | - |

| -30 | 1489.56 | 0.8956 | 2.53E-07 | 0.069 | 5.26E-01 | 4.8 | - |

| -20 | 1460.57 | 0.9073 | 2.35E-07 | 0.071 | 5.39E-01 | 4.4 | - |

| -10 | 1429.49 | 0.9203 | 2.21E-07 | 0.073 | 5.50E-01 | 4 | - |

| 0 | 1397.45 | 0.9345 | 2.14E-07 | 0.073 | 5.57E-01 | 3.8 | - |

| 10 | 1364.3 | 0.9496 | 2.03E-07 | 0.073 | 5.60E-01 | 3.6 | - |

| 20 | 1330.18 | 0.9659 | 1.98E-07 | 0.073 | 5.60E-01 | 3.5 | - |

| 30 | 1295.1 | 0.9835 | 1.94E-07 | 0.071 | 5.60E-01 | 3.5 | - |

| 40 | 1257.13 | 1.0019 | 1.91E-07 | 0.069 | 5.55E-01 | 3.5 | - |

| 50 | 1215.96 | 1.0216 | 1.90E-07 | 0.067 | 5.45E-01 | 3.5 | - |

Gallery

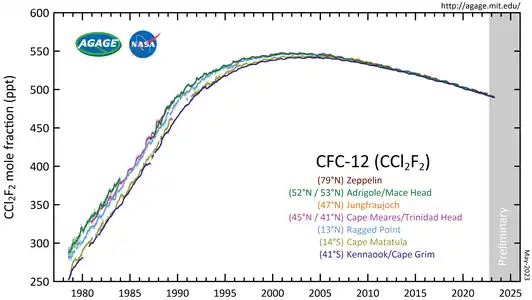

CFC-12 measured by the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) in the lower atmosphere (troposphere) at stations around the world. Abundances are given as pollution free monthly mean mole fractions in parts-per-trillion.

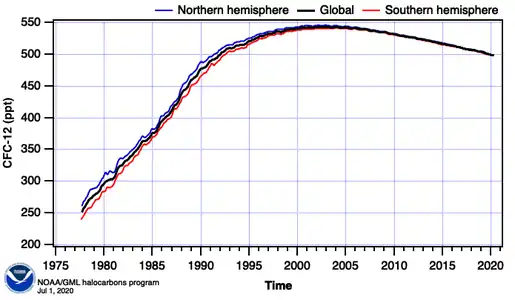

CFC-12 measured by the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) in the lower atmosphere (troposphere) at stations around the world. Abundances are given as pollution free monthly mean mole fractions in parts-per-trillion. Hemispheric and global mean CFC-12 concentrations (NOAA/ESRL)

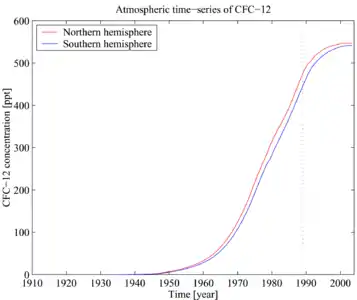

Hemispheric and global mean CFC-12 concentrations (NOAA/ESRL) Time-series of atmospheric concentrations of CFC-12 (Walker et al., 2000)

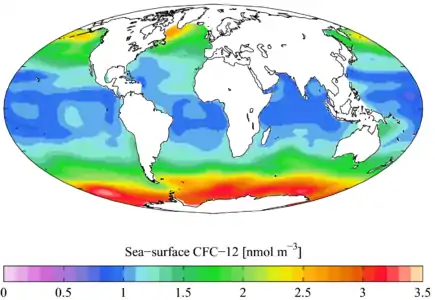

Time-series of atmospheric concentrations of CFC-12 (Walker et al., 2000) 1990s sea surface CFC-12 concentration

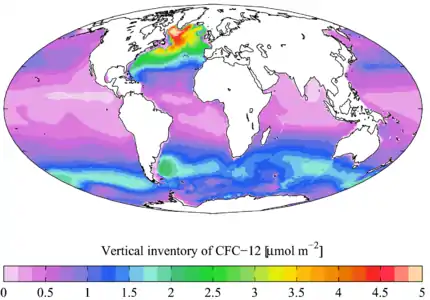

1990s sea surface CFC-12 concentration 1990s CFC-12 oceanic vertical inventory

1990s CFC-12 oceanic vertical inventory CFC-12, CFC-11, H-1211 and SF6 vertical profiles

CFC-12, CFC-11, H-1211 and SF6 vertical profiles

References

- ↑ Touloukian, Y. S., Liley, P. E., and Saxena, S. C. Thermophysical properties of matter – the TPRC data series. Volume 3. Thermal conductivity – nonmetallic liquids and gases. Data book. 1970.

- ↑ Khristenko, Sergei V.; Maslov, Alexander I. and Viatcheslav P. Shevelko; Molecules and Their Spectroscopic Properties, p. 74 ISBN 3642719481.

- 1 2 3 4 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0192". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ "Dichlorodifluoromethane". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ "1:Update on Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODSs) and Other Gases of Interest to the Montreal Protocol". Scientific assessment of ozone depletion: 2018 (PDF) (Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project–Report No. 58 ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization. 2018. p. 1.10. ISBN 978-1-7329317-1-8. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ↑ Plunkett, Roy J. (1986). High Performance Polymers: Their Origin and Development. Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-94-011-7073-4.

- ↑ "Asthma inhaler replacements coming to Pa. - Pittsburgh Tribune-Review". 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 16 February 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ "Se cumplen 13 años de la Tragedia de la Cresta". Ensegundos.com.pa. 23 October 2019.

- ↑ "Victims of the La Cresta tragedy were remembered". M.metrolibra.com. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ "False Alarms: The Legacy of Phosgene Gas". HVAC School. 4 January 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ↑ Holman, Jack P. (2002). Heat Transfer (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 600–606. ISBN 9780072406559.

- ↑ Incropera 1 Dewitt 2 Bergman 3 Lavigne 4, Frank P. 1 David P. 2 Theodore L. 3 Adrienne S. 4 (2007). Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. pp. 941–950. ISBN 9780471457282.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)