| Founded | c. 1860 (BH) 1920s (LCN) |

|---|---|

| Founder | BH: Raffaele Agnello LCN: Silvestro Carollo |

| Founding location | New Orleans, Louisiana |

| Years active | 1880s–present[1][2] |

| Territory | At its peak, all Louisiana state with rings in Texas, Las Vegas and Cuba |

| Ethnicity | Italians as Made Men, Arbereshe other ethnicities as associates |

| Membership | 4-5 made men, 100+ associates (1980s)[3] |

| Leader(s) | Silvestro Carollo (1922–1947) Carlos Marcello (1947–1983) |

| Activities | Racketeering, extortion, gambling, prostitution, narcotics, money laundering, loan sharking, fencing and murder |

| Allies | Chicago Outfit Los Angeles crime family Genovese crime family Gambino crime family Cleveland crime family Trafficante crime family Dixie Mafia[4] |

| Rivals | Minor gangs in New Orleans |

The New Orleans crime family or New Orleans Mafia was an Italian-American Mafia crime family based in the city of New Orleans that had a history of criminal activity dating back to the late nineteenth century.[5] These activities included racketeering, loan sharking, murder, etc. The New Orleans Crime family reached its height of influence under bosses Silvestro Carollo and Carlos Marcello. However, a series of setbacks during the late 20th century reduced the organizations power and local law enforcement as well as the FBI deconstructed what remained of the crime family.

Aside from the family's extensive history with criminal activity, they were also known to have several allies in the criminal community and often partnered with them. Despite the family's apparent downfall, is believed that at least some elements of the American Mafia remain active in New Orleans today.[6][7]

Background

The Matranga Crime Family

The Matranga crime family, established by Charles (1857 - October 28, 1943) and Antonio (Tony) Matranga (d. 1890), was one of the earliest recorded American Mafia crime families, operating in New Orleans during the late 19th century until the beginning of Prohibition in 1920. Silver Dollar Sam (Silvestro Carollo), Carlos Marcello, and Anthony Carollo were the main men associated with the New Orleans Mafia in the 19th Century during the peak of their criminal activities.

Born of Arbëreshë descent and members of the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church in Piana degli Albanesi, Sicily, Carlo and Antonio Matranga immigrated to New Orleans during the 1870s and eventually opened a saloon and brothel. Using their business as a base of operations, the Matranga brothers began establishing lucrative organized criminal activities including extortion and labor racketeering.

Once the Matranga brothers began to put down roots and begin their organized criminal activities, they began receiving tribute payments from Italian laborers and dockworkers, as well as from the Provenzano family. They eventually began moving in on Provenzano fruit loading operations intimidating them with threats of violence.

Although the Provenzanos withdrew in favor of giving the Matrangas a cut of waterfront racketeering, by the late 1880s, the two families eventually went to war over the grocery and produce businesses held by the Provenzanos. As both sides began employing a large number of Sicilian mafiosi from their native Monreale, Sicily, the violent gang war began attracting police attention, particularly from New Orleans police chief David Hennessy who began investigating the warring organizations.

The murder of Hennessey created a huge backlash from the city and, although Charles and several members of the Matrangas were arrested, they were eventually tried and acquitted in February 1891 with Charles Matranga and a 14-year-old member acquitted midway through the trial as well as four more who were eventually acquitted and three others released in hung juries. The decision caused strong protests from residents, angered by the controversy surrounding the case, and the following month a lynch mob stormed the jail killing 11 of the 19 defendants—five of whom had not been tried—on March 14, 1891.

Matranga was able to escape from the vigilante lynchings and, upon returning to New Orleans, resumed his position as head of the New Orleans crime family [8] eventually forcing the declining Provenzanos out of New Orleans by the end of the decade. Because of the Hennessy lynchings, the American Mafia agreed that law enforcement officials should not be harmed in their crossfire. Matranga would rule over the New Orleans underworld until shortly after Prohibition[9] when he turned over leadership over to Sylvestro "Sam" Carollo in the early 1920s.[10]

Influential Figures

Silver Dollar Sam

"Silver Dollar Sam" Carollo led the New Orleans crime family transforming predecessor Charles Matranga's Black Hand gang into a modern organized crime group.[11]

Born in 1896 in Sicily, Carollo immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1904. By 1918, Carollo had become a high-ranking member of Matranga's organization, eventually succeeding him following Matranga's retirement in 1922. Assuming control of Matranga's minor bootlegging operations, Carollo waged war against rival bootlegging gangs, gaining full control following the murder of William Bailey in December 1930.

Gaining considerable political influence within New Orleans, Carollo is said to have used his connections when, in 1929, Al Capone supposedly traveled to the city demanding Carollo supply the Chicago Outfit (rather than Chicago's Sicilian Mafia boss Joe Aiello) with imported alcohol. Meeting Capone as he arrived at a New Orleans train station, Carollo, accompanied by several police officers, reportedly disarmed Capone's bodyguards and broke their fingers, forcing Capone to return to Chicago.

In 1930, Carollo was arrested for the shooting of federal narcotics agent Cecil Moore, which took place during an undercover drug buy. Despite support by several New Orleans police officers who testified Carollo was in New York at the time of the murder, he was sentenced to two years.

Released in 1934, Carollo negotiated a deal with New York mobsters Frank Costello and Phillip "Dandy Phil" Kastel, as well as Louisiana Senator Huey Long, to bring slot machines into Louisiana, following New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia's attacks on organized crime. Carollo, with lieutenant Carlos Marcello, would run illegal gambling operations undisturbed for several years.

Carollo's legal problems continued as he was scheduled to be deported in 1940, after serving two years in Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, following his arrest on a narcotics charge in 1938. His deportation was delayed following the U.S. entry into World War II, and Carollo would continue to control the New Orleans crime family for several years before a campaign, begun by reporter Drew Pearson, exposed an attempt by Congressman James H. Morrison to pass a bill awarding Carollo with American citizenship (thereby making deportation

illegal).[12] Carollo would be deported in April 1947.[13]

Soon after returning to Sicily, Carollo organized a partnership with fellow exile Charles Luciano, establishing criminal enterprises in Mexico. Briefly returning to the United States in 1949, he was deported the following year as control of the New Orleans crime family reverted to Carlos Marcello. Living in Palermo, Sicily until 1970, Carollo once again returned to the US. According to Life Magazine,[5] he was asked to return by Marcello, who needed him to mediate disputes within the New Orleans Mafia. After a subsequent attempt to deport him failed, he died a free man from a heart condition in 1972.[9]

Carlos Marcello

Carlos Marcello was born February 6, 1910 to Sicilian immigrants in Tunis, French Tunisia. He immigrated to the United States in 1911 and settled in Jefferson Parish, a suburb of New Orleans. As a young child and teenager, Marcello often committed petty crimes in the French Quarter. When he was 28 years old in 1938, Marcello was arrested and fined $76,830 for selling 23 pounds (about 10 kilograms) of Marijuana. He faced a lengthy prison sentence but only served 10 months because of he deal he made with Governor Huey Long. This ordeal got him involved with Frank Costello, leader of the Genovese Crime Family in New York City, where he began working for Costello.

By the end of 1947, Marcello had taken control of Louisiana's illegal gambling network. He had also joined forces with New York Mob associate Meyer Lansky in order to take money from some of the most important casinos in the New Orleans area. According to former members of the Chicago Outfit, Marcello was also assigned a cut of the money skimmed from Las Vegas casinos, in exchange for providing "muscle" in Florida real estate deals. By this time, Marcello had been selected as "The Godfather" of the New Orleans Mafia,[14] by the family's capos and the National Crime Syndicate after the deportation of Sylvestro "Silver Dollar Sam" Carollo to Sicily. He held this position for the next 30 years.[15]

On January 25, 1951, Marcello appeared before the U.S. Senate's Kefauver Committee for organized crime. Robert F. Kennedy served as the chief counsel to the committee with his brother, Senator John F. Kennedy. Marcello pleaded the Fifth Amendment 152 times. The Committee called Marcello "one of the worst criminals in the country."[16]

When John F. Kennedy became president, he appointed his brother Robert Kennedy as U.S. Attorney General. With these titles, the two men worked to have Marcello deported to Guatemala[17][18] which was the fake birthplace Marcello had claimed. On April 4, 1961, the U.S. Justice Department, under Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, apprehended Marcello as he made what he assumed was a routine visit to the immigration authorities in New Orleans,[18] then deported him to Guatemala.[19] He struggled to make it back to New Orleans and sustained many injuries on his way back; however, two months later, he was back in New Orleans.[9][20] Thus, he successfully fought efforts by the government to deport him.

In November 1963, Marcello was tried for "conspiracy to defraud the United States government by obtaining a false Guatemalan birth certificate" and "conspiracy to obstruct the United States government in the exercise of its right to deport Carlos Marcello." He was acquitted later that month on both charges. However, in October 1964, Marcello was charged with "conspiring to obstruct justice by fixing a juror [Rudolph Heitler] and seeking the murder of a government witness [Carl Noll]". Marcello's attorney admitted Heitler had been bribed but said that there was no evidence to connect the bribe with Marcello. Noll refused to testify against Marcello in the case. Marcello was acquitted of both charges.[21][22]

In its 1978 investigation of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the House Select Committee on Assassinations said that it recognized Jack Ruby's murder of Lee Harvey Oswald as a primary reason to suspect [23] organized crime as possibly having involvement in the assassination. In its investigation, the HSCA noted the presence of "credible associations relating both Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby to figures having a relationship, albeit tenuous, with Marcello's crime family or organization".[23] Their report stated: "The committee found that Marcello had the motive, means and opportunity to have President John F. Kennedy assassinated, though it was unable to establish direct evidence of Marcello's complicity". Thus, Marcello was free of all accusations of killing John F. Kennedy.[23]

In 1981, Marcello, Aubrey W. Young (a former aide to Governor John J. McKeithen), Charles E. Roemer, II (former commissioner of administration to Governor Edwin Edwards), and two other men were indicted in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana in New Orleans with conspiracy, racketeering, and mail and wire fraud in a scheme to bribe state officials to give the five men multimillion-dollar insurance contracts.[24] The charges were the result of a Federal Bureau of Investigation probe known as BriLab.[25] U.S. District Judge Morey Sear allowed the admission of secretly-recorded conversations that he said demonstrated corruption at the highest levels of state government.[26] Marcello and Roemer were convicted, but Young and the two others were acquitted.[27]

Anthony Carollo

Son of Silvestro Carollo and a New Orleans Mafioso money-lender, Anthony Carollo was born November 24, 1923. Carollo quickly rose to power following his father after serving in the US Army during World War II and owning a restaurant in New Orleans.

In May 1994, following an FBI sting dubbed "Operation Hard Crust", New Orleans crime family acting boss Anthony Carollo with 16 members of the Marcello, Gambino and Genovese families were arrested on charges of infiltrating the newly legalized Louisiana video poker industry,[28] racketeering, illegal gambling and conspiracy.[29] In September 1995, Carollo pleaded guilty to a single count of racketeering conspiracy, with associates Frank Gagliano, Joseph Gagliano, Felix Riggio III, and Cade Carber.[30]

After Carollo's arrest in 1983, his brother Joseph Carollo took over leadership of the family until he stepped down in 1990.[24] After this, the New Orlean Crime Family's whereabouts today are unknown.

Historical leadership

Boss (official and acting)

- c. 1860-1869: Raffaele Agnello – murdered on April 1, 1869

- 1869-1872: Joseph Agnello – murdered on April 20, 1872

- 1872-1891: Joseph P. Macheca – lynched on March 14, 1891

- 1891-1922: Charles Matranga – retired, died on October 28, 1943

- 1922-1944: Corrado Giacona - died on July 25, 1944

- 1944: Frank Todaro - died on November 29, 1944

- 1944-1947: Silvestro "Silver Dollar Sam" Carollo – deported to Italy in 1947

- 1947-1983: Carlos "Little Man" Marcello – imprisoned in 1983–1991

- 1983-1990: Joseph Marcello Jr. – stepped down due to inability to control his organization

- 1990-2007: Anthony Carollo – imprisoned in 1995-1998; died on February 1, 2007

Underboss

- c. 1860-1869: Joseph Agnello – became boss

- 1869-1880: vacant/unknown

- 1880-1881: Vincenzo Rebello – deported to Italy in 1881.

- 1881-1891: Charles Matranga – became boss

- 1891-1896: Salvatore Matranga – died on November 18, 1896[31]

- 1896-1915: Vincenzo Moreci – murdered on November 19, 1915[32]

- 1915-1944: Frank Todaro - became boss, died on November 29, 1944

- 1944-1953: Joseph Poretto – stepped down

- 1953-1983: Joseph Marcello Jr. – became boss

- 1983-2006: Frank "Fat Frank" Gagliano Sr. – died on April 16, 2006

Consigliere

- c. 1950s-1972: Vincenzo "Jimmy" Campo – died in 1972

Societal Influence

Criminal Activity

The family was involved in criminal activities such as racketeering, extortion, gambling, prostitution, narcotics, money laundering, loan sharking, fencing, and murder. The family operated in several locations with their main criminal activity being in New Orleans. In the 1960s, due to Marcello’s stubborn refusal of inducting new members into the family, they dwindled down to a paltry four or five made men with hundreds of associates throughout the United States.[33] However, the Federal Bureau of Investigation believed there were a bit over 20 made men at the time, or 20+ associates so close to Marcello and to each other, that they were considered a formal part of the New Orleans’ family hierarchy.[8][34]

When Carlos Marcello went to jail in the 80's, it sparked issues within New Orleans. The FBI bugged Frank's Deli in the French Quarter in 1993, which was a popular meeting place for mob bosses such as Marcello.[25] The restaurant was bugged as part of an ongoing investigation into how the Mafia was infiltrating the new poker industry in Louisiana.[26][30] FBI wiretaps recorded conversations between the New Orleans Mafia leaders and insight into their operations regarding the Mississippi Gulf Coast.[35] The meeting place chosen by these leaders (Frank's Deli) as well as how they operated helped uncover the loose structure of the New Orleans Mafia[36] and helped send Marcello to jail. When Marcello was sent to jail, the New Orleans Mafia suffered a severe blow and some criminal networks and connections Marcello had at his disposal were not available to future bosses of the crime family due to his imprisonment and the unorganized structure the Mafia had during this time. Marcello also had banned other Mafia families from doing business in New Orleans which caused Anthony Carollo, future boss of the New Orleans crime family, to rid of this rule out of desperation for revenue.

"Little Appalachian" was a meeting between multiple Mafia organizations that served as an important moment in the New Orleans Crime family's' lives. In September 1966, Marcello was summoned to La Stella restaurant in Queens, N.Y. to defend himself at a secret trial for the Mafia. At this meeting, the police came and raided the restaurant, arresting Marcello, Trafficante and the "Judge" of the meeting Cosa Nostra Commissioner Carlo Gambino with charges of "consorting with known criminals." Before the raid took place, however, Marcello successfully defended himself and won his "case." After being released from prison, he greeted FBI agents and reporters with the phrase, "I am the boss here" and proceeded to prove his point by punching FBI Agent Patrick J. Collins. After this, Marcello landed himself back in federal prison for two years. His first trial resulted in a hung jury, but he was retried and convicted. He was sentenced to two years but served less than six months.

Interactions With Other Mafias / Organizations

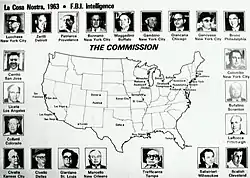

The New Orleans Crime Family was very involved with other criminal groups similar to theirs and had a plethora of allies when it came to the organized crime world. Some of their allies include: Chicago Outfit, Los Angeles Crime Family, Genovese Crime Family, Gambino Crime Family, Cleveland Crime Family, Trafficante crime family, and Dixie Mafia.

The Dixie Mafia interacted heavily with the New Orleans Crime Family. The Dixie Mafia had to be cautious when operating in New Orleans seeing as they did not want to disrupt the activities Marcello, one of the most powerful mafia boss figures, had planned. Occasionally, Marcello and his organization would use the Dixie Mafia to collect their debts and execute certain people.[37] Thus, Marcello allowed the Dixie Mafia to operate in New Orleans so long as the organization followed Marcello's rules. Marcello required that if they were to operate in New Orleans, they could not attract too much attention from cops, had to send a piece of their profits to Marcello, and to not step on any of Marcello's activities or deals. If these rules were disobeyed, Marcello had the guilty killed and tortured.[37]

In popular culture

- The John Grisham novel and film The Client feature a fictionalized New Orleans Mafia family, which is trying to cover up its involvement in a Senator's murder.

- The 1999 HBO movie Vendetta, starring Christopher Walken and directed by Nicholas Meyer, is based on the true story of the March 14, 1891, lynchings of 11 Italians in New Orleans. Charles Matranga (also spelled "Mantranga" in some documents) was one of the intended victims, but managed to survive by hiding from the mob. In the Journal of American History, historian Clive Webb calls the movie a "compelling portrait of prejudice".[38]

- The Marcano Crime Family are a fictionalized version of the New Orleans Crime Family in the 2016 video game Mafia III, which takes place in a fictional version of New Orleans called New Bordeaux, appearing as the main antagonists of the game.

References

- ↑ Rawson, Donald (August 3, 2017). "Bust Card in Biloxi: The Fall of the New Orleans Mafia". Louisiana Mafia.

With the upper echelon of the New Orleans Mafia in jail with enormous restitution to repay, it would be an organization struggling to make it into the new millennium. While the FBI has said modern Italian organized crime still exists in some limited capacity in New Orleans, Anthony Carollo, Frank Gagliano, and Philip Rizzuto would all pass away in the early to mid 2000s with little fanfare. It seems like the New Orleans Mafia, the oldest Mafia organization in the United States, would die with these men.

- ↑ "The Resurgence of the New Orleans Mafia?". Louisiana Mafia. March 12, 2015.

If there are any remnants of the New Orleans Mafia left, and more than likely there is, this incident is probably not an indication of the organization's resurgence.

- ↑ "Mafia on the Bayou — The Marcello Family of New Orleans". Button Guys of the New York Mafia. July 2, 2021.

- ↑ Dixie Mafia Russell McDermott, Texarkana Gazette (December 12, 2013)

- 1 2 Chandler, David (10 April 1970). The Little Man is Bigger than Ever: Louisiana Still Jumps for Mobster Marcello. Life. No. 68. pp. 30–37.

- ↑ Lawton, Dan; Mustian, Jim (July 18, 2014). "'Assassin's van' suggests organized crime elements". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ Grimm, Andy (July 18, 2014). "'Sniper van' found in Metairie leads to mystery with mob ties". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- 1 2 Button Guys of the New York Mafia (July 2, 2021). ""Mafia on the Bayou — The Marcello Family of New Orleans"".

- 1 2 3 "Marcello: Underworld's Man Without a Country". The Owosso Argus-Press. Aug 2, 1965. p. 16.

- ↑ Critchley, David (2008-09-15). The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-85493-5.

- ↑ ""Sylvestro Carollo Reputed Mafia Figure."". The Washington post. Times, Herald. 1970.

- ↑ ""Mafia Racketeer May Be Deported."". The New York Times. 1970. p. 63.

- ↑ ""U. S. Deports New Orleans Vice Overlord."". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1961. p. 13.

- ↑ ""Marcello is tagged as 'Godfather'"". Minden Press-Herald. Minden, Louisiana. January 17, 1975. p. 1.

- ↑ Trillin, Calvin (2010-11-14). "No Daily Specials". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ "The American Mafia - Kefauver Report #3 - May 1, 1951 (B)". 2016-12-20. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ "Meriden Record - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- 1 2 "St. Petersburg Times - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ "Racketeers Deportation Ruled Valid". Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ "Carlos Marcello, 83, Reputed Crime Boss In New Orleans Area". The New York Times. Associated Press. 1993-03-03. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ ""HCSA Report, Volume IX"". Mary Ferrell Foundation. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ "The American Mafia - Kefauver Report #3 - May 1, 1951 (B)". 2016-12-20. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- 1 2 3 ""I.C. The committee believes, on the basis of the evidence available to it, that President John F. Kennedy was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy. The committee was unable to identify the other gunmen or the extent of the conspiracy"". Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 2016-08-15. pp. 149, 171. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- 1 2 Ap (1981-03-31). "AROUND THE NATION; Trial Opens in New Orleans For Reputed Mafia Leader". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- 1 2 Times, Special to the New York (1981-04-22). "ALLEGED UNDERWORLD LEADER IS ASSAILED AT BRIBERY TRIAL". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- 1 2 Times, Special to the New York (1981-05-18). "U.S. TO PLAY MORE TAPES AT LOUISIANA BRIBERY TRAIL". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ Times, Special to the New York (1981-07-08). "EX-LOUISIANA AIDE ACQUITTED IN BRIBERY TRIAL". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ ""Mafia Figure Held in Airport Assault on an F.B.I. Agent:"". The New York Times. 1966. p. 1.

- ↑ "Charges in Louisiana video poker probe - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- 1 2 "LOUISIANA 'CRIME FAMILY' MEMBERS PLEAD GUILTY IN VIDEO POKER CASE". Chicago Tribune. 1995-09-12. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ The Times and Democrat, ed. (1896). "Salvatore Matranga, New Orleans 1896 Nov 15". Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Critchley, David (2008). Routledge (ed.). The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. Routledge. pp. 59–60. ISBN 9781135854935.

- ↑ Tosches, Nick (1993). ""Mafia a Go-Go the Unwritten History of Rock 'n' Roll."". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Pearson, Drew (1952). ""Gangsters' Tax Pay-Ups Secret."". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Jail Sentences Handed down in Video Poker Case". Las Vegas Review. Associated Press. 1996. pp. Journal: 8.B.

- ↑ Smith, John (1994). ""Latest Louisiana Scandal Was Simply Business as Usual."". Las Vegas Review. pp. Journal 1b.

- 1 2 McDermott, Russell (2013-12-02). "DIXIE MAFIA | Texarkana Gazette". Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ Webb, Clive (2000). "Review". The Journal of American History. Oxford University Press. 87 (3): 1155–1156. doi:10.2307/2675451. JSTOR 2675451.

Further reading

- Steece, David. "david steece's Paradox, The True Narrative of a Real Street Man" Paradox Sales, www.davidsteece.com 2009 ISBN 1-4392-6351-5

- Brouillette, Frenchy. Mr. New Orleans: The Life of a Big Easy Underworld Legend, Phoenix Books, 2009.

- Davis, John H. Mafia Kingfish: Carlos Marcello and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy. New York: Signet, 1989. ISBN 0-520-08410-1

- Fentress, James. Rebels and Mafiosi: Death in a Sicilian Landscape. New York: Cornell University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8014-3539-0

- Kelly, Robert J. Encyclopedia of Organized Crime in the United States. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30653-2

- Kurtz, Michael L. (Autumn 1983). "Organized Crime in Louisiana History: Myth and Reality". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 24 (4): 355–376. JSTOR 4232305.

- Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. New York, N.Y.: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1429907989.

- Reppetto, Thomas. American Mafia: A History of Its Rise to Power. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2004. ISBN 0-8050-7798-7

- Scott, Peter Dale and Marshall, Jonathan. Cocaine Politics: Drugs, Armies, and the CIA in Central America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. ISBN 0-520-07312-6

- Sifakis, Carl. The Mafia Encyclopedia. New York: Da Capo Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8160-5694-3

- Sifakis, Carl. The Encyclopedia of American Crime. New York: Facts on File Inc., 2001. ISBN 0-8160-4040-0

- Summers, Anthony. Conspiracy. New York: McGraw & Hill, 1989.

- Rappleye, Charles. All American Mafiosi. New York: Doubleday, 1991.

External links

- LAM: A Site Dedicated to the History of the Louisiana Mafia by Dexter Babin II

- David "Blackie" Steece - The True Narrative of a Real Street Man - New Orleans Gangster Turned Law Enforcer Autobiography

- Carlos Marcello: Big Daddy in the Big Easy by Thomas L. Jones

- Sylvestro Carollo: Will the Real "Silver Dollar Sam" Please Stand Up by Allan May

- The American "Mafia": Who Was Who ? – Charles Matranga

- The American "Mafia" – New Orleans Crime Bosses