Caroline Spencer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 30, 1861 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | September 16, 1928 (aged 66) Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Physician, activist |

Caroline Spencer (October 30, 1861 – September 16, 1928) was an American physician and suffragist who campaigned extensively for women's rights, both in her home state of Colorado and on the national level. She was one of many Silent Sentinels who demonstrated in front of the White House, and also participated in Watchfires, during the final months before the Nineteenth amendment was passed. She was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 2006.[1]

Early life and education

Caroline E. Spencer, daughter of J. Austin Spencer, an attorney, and Anna Brock Spencer, was born in 1861 in Philadelphia. Her mother died when Caroline Spencer was nine years old. Spencer attended the Philadelphia Normal School For Girls, where she received the Hannah M. Dodd Medal of Merit for her scholastic achievement. Following her graduation in 1880, she was employed at the Normal School, teaching history, for a period of time before enrolling in the Women's Medical College, Philadelphia, where she earned her medical degree in 1892. She practiced medicine throughout the remainder of her life.[2]

Spencer suffered from chronic bronchitis and asthma and in 1889, she visited Colorado hoping that the climate would be beneficial. Four years later, after obtaining her medical degree, she moved to the state, and settled in Colorado Springs.[3]

Activism

In Colorado, Spencer became active in the Woman's Suffrage Movement.[2][3] She was a founder of the Women's Club of Colorado Springs (1902) as well as of the Civic League (1909).[1][2] The Civic League, which championed both women's rights and labor rights, ran afoul of business interests in the state and was eventually forced to close, in 1914.[3] Since Colorado women had gained the vote at the state level in an 1893 referendum, Spencer and her local allies focused their efforts on legislation at the national level, primarily on passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution.![3] In 1913, Spencer joined Alice Paul's Congressional Union, which later became the National Woman's Party.[2][3]

Colorado Springs became the CU/NWP headquarters in the state, and Spencer herself was recognized as an able leader of her state's radical feminist wing.[3] She helped to stage numerous local suffragist publicity events and Colorado Springs became a stop-off point for cross-country car and train tours known as "Suffrage Specials."[3]

I accept my sentence under protest because of my innocence of any unlawful act, for the purpose of showing the nation that the women voters are equal to any sacrifice necessary to secure political freedom.

— Caroline Spencer[3]

Spencer also took part in a number of public demonstrations for women's rights, both in Colorado and Washington D.C. In 1916, she protested speeches by William Jennings Bryan in Colorado and President Woodrow Wilson in Washington, D.C.[1] On December 5, 1916, she sat in the front row of the balcony, with four other suffragists, during the President's annual speech to Congress. As President Woodrow Wilson began to speak, they unfurled a banner over the side of the balcony which stated "Mr. President, What Will You Do For Woman Suffrage?" Wilson did not acknowledge the presence of the banner and a Senate page ripped it down and discarded it. However, the women did receive national recognition, following this event, as it was reported by journalists who were present.[1][4]

Between 1917 and 1919, Spencer was one of many women who became known as the Silent Sentinel, as they stood in front of the White House and carried pickets and banners for their cause. Although it was not illegal to picket, after the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Alice Paul was warned by police that arrests would be made if the women continued. Caroline Spencer was arrested on three occasions and subsequently imprisoned twice.[1][3]

On October 6, 1917, eleven women, including Spencer, marched from the Capital Building, where the Emergency War Session of the 65th Session of Congress was being held, to the White House. The women carried banners as they walked and were attacked by a group of men who pulled down the banners, while police stood by and watched. The eleven women were arrested and charged with obstruction of traffic. Two days later, a judge suspended the sentences of all eleven and they were released.[5]

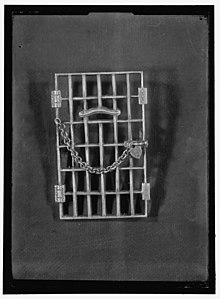

On October 20, 1917, Spencer was again arrested, along with Alice Paul, Gladys Grenier and Gertrude Crocker, while picketing at the west gate of the White House. Following their trial, both Paul and Spencer, who were carrying banners, were given 7 month sentences; Grenier and Crocker were given the choice of a $5 fine or 30 days in jail. They refused to pay a fine and were jailed.[5] During her imprisonment in a dusty cell with no fresh air available, Spencer suffered a severe asthma attack and a physician ordered her release.[3] She later received a silver brooch shaped like a prison door that Alice Paul had made for the 90 women who served jail terms as a result of picketing the White House over women's rights.[6]

Following her release, Spencer returned to Colorado for a long period of recuperation. In late 1918, she wrote to Alice Paul, stating her desire to return to Washington when the amendment vote approached.[3] In December, while the president was traveling throughout Europe in support of the peace talks, the suffragists held a ceremony in front of the White House. Each woman spoke and burned copies of Wilson's speeches. Spencer was in attendance and repeated the words Wilson had spoken at the tomb of Lafayette, before she burned a copy of his speech, "in memory of the great Lafayette -- from a fellow servant of liberty."[5]

Later that month, a decision was made by the National Women's Party to continue the "Watchfires" until the Susan B. Anthony Amendment was passed. On January 1, 1919, a cauldron was set up in front of the White House to hold the fire; suffragists were asked to contribute wood from their home-states to keep it burning. Police periodically put out the fires and made arrests. January 18, Spencer relighted the fire, using wood she had brought from Colorado, then began burning copies of Wilson's latest speeches on the subject of "rights and justice." She was arrested, along with twenty-two other women, and was sentenced to jail.[5]

On June 4, 1919, the amendment was passed; now the work turned to ratification by three-quarters of the states.

Later life

Following the passage of the amendment, Spencer returned home to Colorado to work with the Woman's Party at the state level. On December 12, 1920, the Colorado legislature passed the ratification of the 19th Amendment.[6]

Following the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, Spencer continued the fight for women's rights. In 1922, she helped to create the Philadelphia branch of the National Women's Party. Two years later, she assisted in organizing a rally with the goal of obtaining congressional representation for women in Pennsylvania.[2]

After being diagnosed with tuberculosis, Spencer left Colorado and returned to live with her sister in Pennsylvania, where she died on September 16, 1928.

In 2006, Spencer was honored by the state of Colorado when she was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame.[1][2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Caroline Spencer MD". Colorado Women's Hall of Fame website.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Dr. Caroline E. Spencer". Turning Point Suffragist Memorial. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Nicholl, Chris. "Dr. Caroline Spencer & Colorado Springs' Radicals for Reform". Extraordinary Women of the Rocky Mountain West. pp. 245–289

- ↑ "Detailed Chronology--National Woman's Party History" (PDF). American Memory.

- 1 2 3 4 Gillmore, Inez Haynes (1921). The Story of the Woman's Party. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. p. 410.

caroline spencer, suffrage.

- 1 2 The Suffragist. Washington D.C.: National Woman's Party. 1920. pp. 26, 226, 334.

Further reading

- Stevens, Doris (1920). Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni & Liveright. pp. 213, 308, 345, 368. At the Internet Archive: Copy 1; Copy 2.

.jpg.webp)