_(6102602781).jpg.webp)

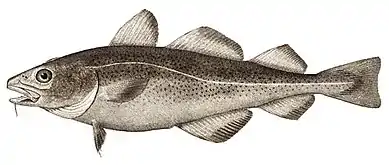

The term carp (pl.: carp) is a generic common name for numerous species of freshwater fish from the family Cyprinidae, a very large clade of ray-finned fish mostly native to Eurasia. While carp are prized quarries and are valued (even commercially cultivated) as both food and ornamental fish in many parts of the Old World,[1] they are generally considered useless trash fish and invasive pests in many parts of Africa, Australia and most of the United States.[2][3]

Biology

The cypriniformes (family Cyprinidae) are traditionally grouped with the Characiformes, Siluriformes, and Gymnotiformes to create the superorder Ostariophysi, since these groups share some common features. These features include being found predominantly in fresh water and possessing Weberian ossicles, an anatomical structure derived from the first five anterior-most vertebrae, and their corresponding ribs and neural crests.

The third anterior-most pair of ribs is in contact with the extension of the labyrinth and the posterior with the swim bladder. The function is poorly understood, but this structure is presumed to take part in the transmission of vibrations from the swim bladder to the labyrinth and in the perception of sound, which would explain why the Ostariophysi have such a great capacity for hearing.[4]

Most cypriniformes have scales and teeth on the inferior pharyngeal bones which may be modified in relation to the diet. Tribolodon is the only cyprinid genus which tolerates salt water. Several species move into brackish water but return to fresh water to spawn. All of the other cypriniformes live in continental waters and have a wide geographical range.[4] Some consider all cyprinid fishes carp, and the family Cyprinidae itself is often known as the carp family.

In colloquial use, carp usually refers only to several larger cyprinid species such as Cyprinus carpio (common carp), Carassius carassius (crucian carp), Ctenopharyngodon idella (grass carp), Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (silver carp), and Hypophthalmichthys nobilis (bighead carp).

Carp have long been an important food fish to humans. Several species such as the various goldfish (Carassius auratus) breeds and the domesticated common carp variety known as koi (Cyprinus rubrofuscus var. "koi") have been popular ornamental fishes. As a result, carp have been introduced to various locations, though with mixed results. Several species of carp are considered invasive species in the United States,[5] and, worldwide, large sums of money are spent on carp control.[6]

At least some species of carp are able to survive for months with practically no oxygen (for example under ice or in stagnant, scummy water) by metabolizing glycogen to form lactic acid which is then converted into ethanol and carbon dioxide. The ethanol diffuses into the surrounding water through the gills.[7][8][9]

Species

| This article is part of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| Forage |

| Demersal |

| Mixed |

| Some prominent carp in the family Cyprinidae | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Max length (cm) |

Common length (cm) |

Max weight (kg) |

Max age (yr) |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | ITIS | IUCN status |

| Silver carp | Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes, 1844) | 105 | 18 | 50 | 2.0 | [10] | [11] | [12] | ||

| Common carp (European carp) | Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758) | 110 | 31 | 40.1 | 38 | 3.0 | [14] | [15] | [16] | |

| Grass carp | Ctenopharyngodon idella (Valenciennes, 1844) | 150 | 10.7 | 45.0 | 21 | 2.0 | [18] | [19] | Not assessed | |

| Bighead carp | Hypophthalmichthys nobilis (Richardson, 1845) | 146 | 60 | 40.0 | 20 | 2.3 | [20] | [21] | ||

| Crucian carp | Carassius carassius (Linnaeus, 1758) | 64 | 15 | 3.0 | 10 | 3.1 | [23] | [24] | ||

| Catla carp (Indian carp) | Cyprinus catla (Hamilton, 1822) | 182 | 38.6 | 2.8 | [25] | [26] | Not assessed | |||

| Mrigal carp | Cirrhinus cirrhosus (Bloch, 1795) | 100 | 40 | 12.7 | 2.5 | [27] | [28] | |||

| Black carp | Mylopharyngodon piceus (Richardson, 1846) | 122 | 12.2 | 35 | 13 | 3.2 | [30] | [31] | Not assessed | |

| Mud carp | Cirrhinus molitorella (Valenciennes, 1844) | 55.0 | 15.2 | 0.50 | 2.0 | [32] | [33] | |||

Recreational fishing

In 1653 Izaak Walton wrote in The Compleat Angler, "The Carp is the queen of rivers; a stately, a good, and a very subtle fish; that was not at first bred, nor hath been long in England, but is now naturalised."

Carp are variable in terms of angling value.

- In Europe, even when not fished for food, they are eagerly sought by anglers, being considered highly prized coarse fish that are difficult to hook.[34] The UK has a thriving carp angling market, with the British record carp standing at 68lb 1oz.[35] It is the fastest growing angling market in the UK, and has spawned a number of specialised carp angling publications such as Carpology,[36] Advanced carp fishing, Carpworld[37] and Total Carp, and informative carp angling web sites, such as Carpfishing UK[38] and Carp Squad.

- In the United States, carp are also classified as a rough fish, as well as a damaging naturalized exotic species, but with sporting qualities. Carp have long suffered from a poor reputation in the United States as undesirable for angling or for the table, especially since they are typically an invasive species out-competing more desirable local game fish. Nonetheless, many states' departments of natural resources are beginning to view the carp as an angling fish instead of a maligned pest. Groups such as Wild Carp Companies,[39] American Carp Society,[40] and the Carp Anglers Group[41] promote the sport and work with fisheries departments to organize events to introduce and expose others to the unique opportunity the carp offers freshwater anglers.

Aquaculture

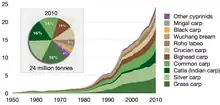

Various species of carp have been domesticated and reared as food fish across Europe and Asia for thousands of years. These various species appear to have been domesticated independently, as the various domesticated carp species are native to different parts of Eurasia. Aquaculture has been pursued in China for at least 2,400 years. A tract by Fan Li in the fifth century BC details many of the ways carp were raised in ponds.[43] The common carp (Cyprinus carpio) is originally from Central Europe.[44] Several carp species (collectively known as Asian carp) were domesticated in East Asia. Carp that are originally from South Asia, for example catla (Gibelion catla), rohu (Labeo rohita) and mrigal (Cirrhinus cirrhosus), are known as Indian carp. Their hardiness and adaptability have allowed domesticated species to be propagated all around the world.

Although the carp was an important aquatic food item, as more fish species have become readily available for the table, the importance of carp culture in Western Europe has diminished. Demand has declined, partly due to the appearance of more desirable table fish such as trout and salmon through intensive farming, and environmental constraints. However, fish production in ponds is still a major form of aquaculture in Central and Eastern Europe, including the Russian Federation, where most of the production comes from low or intermediate-intensity ponds. In Asia, the farming of carp continues to surpass the total amount of farmed fish volume of intensively sea-farmed species, such as salmon and tuna.[45]

Breeding

Selective breeding programs for the common carp include improvement in growth, shape, and resistance to disease. Experiments carried out in the USSR used crossings of broodstocks to increase genetic diversity, and then selected the species for traits such as growth rate, exterior traits and viability, and/or adaptation to environmental conditions such as variations in temperature.[46][47] Selected carp for fast growth and tolerance to cold, the Ropsha carp. The results showed a 30 to 77.4% improvement of cold tolerance, but did not provide any data for growth rate. An increase in growth rate was observed in the second generation in Vietnam,[48] Moav and Wohlfarth (1976) showed positive results when selecting for slower growth for three generations compared to selecting for faster growth.[49] Schaperclaus (1962) showed resistance to the dropsy disease wherein selected lines suffered low mortality (11.5%) compared to unselected (57%).[50]

The major carp species used traditionally in Chinese aquaculture are the black, grass, silver and bighead carp. In the 1950s, the Pearl River Fishery Research Institute in China made a technological breakthrough in the induced breeding of these carps, which has resulted in a rapid expansion of freshwater aquaculture in China.[51] In the late 1990s, scientists at the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences developed a new variant of the common carp called the Jian carp (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian). This fish grows rapidly and has a high feed conversion rate. Over 50% of the total aquaculture production of carp in China has now converted to Jian carp.[51][52]

| The major traditional aquaculture carp of China | |||

|---|---|---|---|

As ornamental fish

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Carp, along with many of their cyprinid relatives, are popular ornamental aquarium and pond fish.

Ornamental goldfish were originally domesticated from their wild form, a dark greyish-brown carp native to Asia, but may have been influenced by Carassius carassius and Carassius gibelio. They were first bred for color in China over a thousand years ago. Due to selective breeding, goldfish have been developed into many distinct breeds, and are found in various colors, color patterns, forms and sizes far different from those of the original carp. Goldfish were kept as ornamental fish in China for thousands of years before being introduced to Japan in 1603, and to Europe in 1611.[53]

Nishikigoi, better known simply as koi, are a domesticated varieties of common carp and Amur carp (Cyprinus rubrofuscus) that have been selectively bred for color. The common carp was introduced from China to Japan, where selective breeding in the 1820s in the Niigata region resulted in koi.[54] In Japanese culture, koi are treated with affection, and seen as good luck.[55] They are popular in other parts of the world as outdoor pond fish.[56]

As food

- Bighead carp is enjoyed in many parts of the world, but it has not become a popular foodfish in North America. Acceptance there has been hindered in part by the name "carp", and its association with the common carp which is not a generally favored foodfish in North America. The flesh of the bighead carp is white and firm, different from that of the common carp, which is darker and richer. Bighead carp flesh does share one unfortunate similarity with common carp flesh – both have intramuscular bones within the filet. However, bighead carp captured from the wild in the United States tend to be much larger than common carp, so the intramuscular bones are also larger and thus less problematic.

- Common carp, breaded and fried, is part of traditional Christmas Eve dinner in Slovakia, Poland, eastern part of Croatia and in the Czech Republic. In pond based water agriculture it is treated as most prominent food fish.

- Crucian carp is considered the best-tasting pan fish in Poland. It is known as karaś, and is served traditionally with sour cream (karasie w śmietanie).[57] In Russia, this particular species is called Золотой карась, meaning "golden crucian", and is one of the fish used in a borscht recipe called borshch s karasej[58] (Борщ с карасе́й) or borshch s karasyami Борщ с карася́ми).

- Mud carp, due to the low cost of production, is mainly consumed by the poor, locally; it is mostly sold alive, but can be dried and salted.[59] The fish is sometimes canned or processed as fish cakes, fish balls,[60] or dumplings. They can be found for retail sale within China.[59]

- Chinese mud carp is an important food fish in Guangdong Province. It is also cultured in this area and Taiwan. Cantonese and Shunde cuisines often use this fish to make fish balls and dumplings. It can be used with douchi or Chinese fermented black beans in a dish called fried dace with salted black beans. It can be served cooked with vegetables such as Chinese cabbage.

- Fisherman's soup

- Kuai

- Taramosalata

- Masgouf, a popular Iraqi dish consisting of seasoned, grilled carp.

- Gefilte fish, an Ashkenazi Jewish dish made from a poached mixture of ground deboned fish, primarily carp, whitefish, and pike.

Gallery

- Carp-based dishes

Catla kalia – a popular fish curry preparation from West Bengal, India

Catla kalia – a popular fish curry preparation from West Bengal, India Carp curry, India

Carp curry, India Fried carp from Franconia, Germany

Fried carp from Franconia, Germany Pan-fried Crucian carp, Russia

Pan-fried Crucian carp, Russia Traditional Christmas dinner – fried carp with potato salad, Czech Republic

Traditional Christmas dinner – fried carp with potato salad, Czech Republic Stir-fried Crucian carp with rice, Japan

Stir-fried Crucian carp with rice, Japan_Sunda.jpg.webp) Carp fish in spices and herbs cooked in a banana leaf package, Sundanese

Carp fish in spices and herbs cooked in a banana leaf package, Sundanese Deep-fried chunk of pickled (pla som) silver barb (Pla taphian)

Deep-fried chunk of pickled (pla som) silver barb (Pla taphian) Barbecued carp, northern Croatia

Barbecued carp, northern Croatia

See also

References

- ↑ "Short Reports - How to Cook a Carp". TPWD. Texas. Archived from the original on 2023-03-26. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ↑ "What are Invasive Carp?". USGS. United States. Archived from the original on 2023-05-16. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ↑ "Carp in the Murray-Darling Basin and Commonwealth environmental water". DCCEEW. Commonwealth of Australia. 2022. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- 1 2 Billard R. (Ed.) (1995). Carp – Biology and Culture. Springer-Praxis Series in Aquaculture and Fisheries, Chichester, UK.

- ↑ National Invasive Species Information Center (2010-07-21). "Invasive Species: Aquatic Species – Asian Carp". Invasivespeciesinfo.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ↑ "Karpfenstuhl". Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ↑ Aren van Waarde; G. Van den Thillart; Maria Verhagen (1993). "Ethanol Formation and pH-Regulation in Fish". Surviving Hypoxia. pp. 157–170. hdl:11370/3196a88e-a978-4293-8f6f-cd6876d8c428. ISBN 0-8493-4226-0.

- ↑ "Breath of life: Did animals evolve without oxygen?". New Scientist. Jan 21, 2017.

- ↑ Jay Storz & Grant McClelland (Apr 21, 2017). "Rewiring metabolism under oxygen deprivation". Science. 356 (6335): 248–249. Bibcode:2017Sci...356..248S. doi:10.1126/science.aan1505. PMC 6661067. PMID 28428384.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Hypophthalmichthys molitrix" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes, 1844) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved May 2012.

- ↑ "Hypophthalmichthys molitrix". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ Zhao, H.H. (2011). "Hypophthalmichthys molitrix". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T166081A6168056. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T166081A6168056.en. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Cyprinus carpio" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved May 2012.

- ↑ "Cyprinus carpio". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- 1 2 Freyhof, J.; Kottelat, M. (2008). "Cyprinus carpio". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T6181A12559362. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T6181A12559362.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Ctenopharyngodon idella" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Ctenopharyngodon idella". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Hypophthalmichthys nobilis" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Hypophthalmichthys nobilis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- 1 2 Freyhof, J.; Kottelat, M. (2008). "Carassius carassius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T3849A10117321. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3849A10117321.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Carassius carassius" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Carassius carassius". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Cyprinus catla" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Cyprinus catla". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Cirrhinus cirrhosus" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Cirrhinus cirrhosus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ Rema Devi, K.R.; Ali, A. (2011). "Cirrhinus cirrhosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T166531A6230103. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T166531A6230103.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Mylopharyngodon piceus" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Mylopharyngodon piceus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Cirrhinus molitorella" in FishBase. May 2012 version.

- ↑ "Cirrhinus molitorella". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ A. F. Magri MacMahon (1946). Fishlore, pp 149–152. Pelican Books.

- ↑ Warburton, Rob (13 April 2023). "British Carp Record". Carp Squad.

- ↑ "CARPology Magazine". www.carpology.net.

- ↑ "Carpworld Magazine". www.carpworld.co.uk.

- ↑ "Carp Fishing - Carpfishing UK". www.carp-uk.net.

- ↑ "Carp Fishing in Syracuse and Baldwinsville areas, NY, USA. Wild Carp Companies, of Baldwinsville, NY, promotes catch and release carp angling". www.wildcarpcompanies.com.

- ↑ "Coming Soon". American Carp Society.

- ↑ "Carp Anglers Group".

- ↑ Based on data sourced from the FishStat database

- ↑ National Aquaculture Sector Overview: China FAO, Rome. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Zhou, Jian Feng; Wu, Qing Jiang; Ye, Yu Zhen; Tong, Jin Gou (2003). "Genetic Divergence Between Cyprinus carpio carpio and Cyprinus carpio haematopterus as Assessed by Mitochondrial DNA Analysis, with Emphasis on Origin of European Domestic Carp". Genetica. 119 (1): 93–97. doi:10.1023/A:1024421001015. PMID 12903751. S2CID 36805144.

- ↑ Váradi, L. (2001). Review of trends in the development of European inland aquaculture linkages with fisheries. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 8: 453–462.

- ↑ Kirpichnikov, V.S.; Ilyasov, J.I.; Shart, L.A.; Vikhman, A.A.; Ganchenko, M.V.; Ostashevsky, A.L.; Simonov, V.M.; Tikhonov, G.F; Tjurin, V.V. (1993). "Selection of Krasnodar common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) for resistance to dropsy: principal results and prospects". Aquaculture. 111 (1–4): 7–20. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(93)90020-Y.

- ↑ Babouchkine, Y.P., 1987. La sélection d’une carpe résistant à l’hiver. In: Tiews, K. (Ed.), Proceedings ofWorld Symposium on Selection, Hybridization, and Genetic Engineering in Aquaculture, Bordeaux 27–30 May 1986, vol. 1. HeenemannVerlagsgesellschaft mbH, Berlin, pp. 447–454.

- ↑ Tran, M.T.; Nguyen, C.T. (1993). "Selection of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) in Vietnam". Aquaculture. 111 (1–4): 301–302. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(93)90064-6.

- ↑ Moav, R.; Wohlfarth, G.W. (1976). "Two-way selection for growth rate in the common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.)". Genetics. 82 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1093/genetics/82.1.83. PMC 1213447. PMID 1248737.

- ↑ Schäperclaus, W. 1962. Traité de pisciculture en étang. Vigot Frères, Paris

- 1 2 CAFS research achievement Archived 2012-03-28 at the Wayback Machine CAFS. Accessed 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Jian, Zhu; Jianxin, Wang; Yongsheng, Gong and Jiaxin, Chen (2005) "Carp Genetic Resources of China" pp. 26–38. In: David J Penman, Modadugu V Gupta and Madan M Dey (Eds.) Carp genetic resources for aquaculture in Asia, WorldFish Center, Technical report: 65(1727). ISBN 978-983-2346-35-7.

- ↑ "Goldfish history, colour and finnage, diseases, how to keep them, and how to breed them". bristol-aquarists.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-01-18.

- ↑ "Midwest Pond and Koi Society – Koi History: Myths & Mysteries, by Ray Jordan". Mpks.org. Archived from the original on 2009-07-23. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Goto, Mao (November 24, 2021). "The History of Koi and Their Meaning in Japan". Japan Wonder Travel Blog. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Japan's Koi fish gaining popularity around world". Asian News International. May 25, 2020.

- ↑ Strybel & Strybel 2005, p. 384

- ↑ Molokhovet︠s︡ 1998

- 1 2 "Cultured Aquatic Species – Mud Carp". TheFishSite.com. 10 December 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-05-22. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ Grygus, Andrew. "Carp Family". www.clovegarden.com.

- Strybel, Robert; Strybel, Maria (2005). Polish Heritage Cookery. Hippocrene Books. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-7818-1124-8.

- Molokhovet︠s︡, Elena (1998). Classic Russian Cooking: Elena Molokhovets' a Gift to Young Housewives. Indiana University Press. p. 674. ISBN 978-0-253-21210-8.

External links

The dictionary definition of carp at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of carp at Wiktionary Media related to Carp at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carp at Wikimedia Commons- Chistiakov D, Voronova N (2009). "Genetic evolution and diversity of common carp Cyprinus carpio L." Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 4 (3): 304–312. doi:10.2478/s11535-009-0024-2.

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)