Marine mammals are a food source in many countries around the world. Historically, they were hunted by coastal people, and in the case of aboriginal whaling, still are. This sort of subsistence hunting was on a small scale and produced only localised effects. Dolphin drive hunting continues in this vein, from the South Pacific to the North Atlantic. The commercial whaling industry and the maritime fur trade, which had devastating effects on marine mammal populations, did not focus on the animals as food, but for other resources, namely whale oil and seal fur.

Today, the consumption of marine mammals is much reduced. However, a 2011 study found that the number of humans eating them, from a surprisingly wide variety of species, is increasing.[1] According to the study's lead author, Martin Robards, "Some of the most commonly eaten animals are small cetaceans like the lesser dolphins... That was a surprise since only a decade ago there had only been only scattered reports of this happening".[2]

History

Historically, marine mammals were hunted by coastal aboriginal humans for food and other resources. The effects of this were only localised as hunting efforts were on a relatively small scale.[3] Later, commercial hunting was developed and marine mammals were heavily exploited. This led to the extinction of the Steller's Sea Cow and the Caribbean monk seal.[3] Today, populations of species that were historically hunted, such as blue whales Balaenoptera musculus and B. m. brevicauda), and the North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica), are much lower compared to their pre-exploited levels.[4] Because whales generally have slow growth rates, are slow to reach sexual maturity, and have a low reproductive output, population recovery has been very slow.[5] Despite the fact commercial whaling is generally a thing of the past since the passage of the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling, a number of marine mammals are still subject to direct hunting. The only remaining commercial hunting of whales is by Norway where several hundred northeastern North Atlantic minke whales are harvested each year, and Iceland, which takes approximately 150 North Atlantic fin whales and less than 50 minke whales each year. Japan also harvests several hundred Antarctic and North Pacific minke whales each year under the guise of scientific research.[4] However, the illegal trade of whale and dolphin meat is a significant market in some countries.[6] Seals and sealions are also still hunted in some areas such as Canada.

Overview

For thousands of years, Arctic people have depended on whale meat. In Alaska now, the meat is harvested from legal, non-commercial hunts that occur twice a year in the spring and autumn. The meat is stored and eaten throughout the winter.[7] Coastal Alaska Natives divided their catch into 10 sections. The fatty tail, considered to be the best part, went to the captain of the conquering vessel, while the less-desired sections were given to his crew and others that assisted with the kill.[8] The skin and blubber (muktuk) taken from the bowfin, beluga, or narwhal is also valued, and is eaten raw or cooked.

In recent years Japan resumed hunting for whales, which they call "research whaling". Japanese research vessels refer to the harvested whale meat as incidental byproducts resulting from lethal study. In 2006, 5,560 tons of whale meat was sold for consumption.[9] In modern-day Japan, two cuts of whale meat are usually distinguished: the belly meat and the tail or fluke meat. Fluke meat can sell for $200 per kilogram, over three times the price of belly meat.[8] Fin whales are particularly desired because they are thought to yield the best quality fluke meat.[10]

In some parts of the world, such as Taiji in Japan and the Faroe Islands, dolphins are traditionally considered food, and are killed in harpoon or drive hunts.[11] Whaling has also been practiced in the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic since about the time of the first Norse settlements on the islands. Around 1000 Long-finned pilot whales are still killed annually, mainly during the summer.[12]

Dolphin meat is consumed in a small number of countries world-wide, which include Japan[13] and Peru (where it is referred to as chancho marino, or "sea pork").[14] While Japan may be the best-known and most controversial example, only a very small minority of the population has ever sampled it.

In Taiwan, demand for dolphin meat still exists. Despite laws banning the slaughter of dolphins and jail-time consequences for anyone who consumes dolphin meat, as many as 1,000 dolphins are killed by Taiwanese fishermen each year.[15]

Dolphin meat is dense and such a dark shade of red as to appear black. Fat is located in a layer of blubber between the meat and the skin. When dolphin meat is eaten in Japan, it is often cut into thin strips and eaten raw as sashimi, garnished with onion and either horseradish or grated garlic, much as with sashimi of whale or horse meat (basashi). When cooked, dolphin meat is cut into bite-size cubes and then batter-fried or simmered in a miso sauce with vegetables. Cooked dolphin meat has a flavor very similar to beef liver.[16] Dolphin meat is high in mercury, and may pose a health danger to humans when consumed.[17]

Ringed seals were once the main food staple for the Inuit. They are still an important food source for the people of Nunavut[18] and are also hunted and eaten in Alaska. Seal meat is an important source of food for residents of small coastal communities.[19] Meat is sold to the Asian pet food market; in 2004, only Taiwan and South Korea purchased seal meat from Canada.[20] The seal blubber is used to make seal oil, which is marketed as a fish oil supplement. In 2001, two percent of Canada's raw seal oil was processed and sold in Canadian health stores.[21] There has been virtually no market for seal organs since 1998.[19] Archaeological evidence indicates that for thousands of years, indigenous peoples have also hunted sea otters for food and fur.[22]

Makah whalers removing strips of flesh from a whale carcass at Neah Bay, Washington

Makah whalers removing strips of flesh from a whale carcass at Neah Bay, Washington Whale meat on sale at Tsukiji fish market, Tokyo

Whale meat on sale at Tsukiji fish market, Tokyo

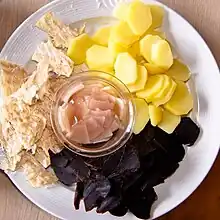

Pilot whale meat (bottom), blubber (middle) and dried fish (left) with potatoes, Faroe Islands

Pilot whale meat (bottom), blubber (middle) and dried fish (left) with potatoes, Faroe Islands

See also

References

- 1 2 Robards MD and Reeves RR (2011) "The global extent and character of marine mammal consumption by humans: 1970–2009" Biological Conservation, 144(12): 2770–2786.

- ↑ Edible Marine Mammals: Study Finds 87 Species Are Eaten Around The World Huffington Post. Updated: 27 January 2012.

- 1 2 Berta, A & Sumich, J. L. (1999) Marine mammals: evolutionary biology. San Diego: Academic Press ISBN 0-12-093225-3

- 1 2 Clapham, P. J., Young, S. B. & Brownel Jr, R. L. (1999) "Baleen whales: conservation issues and the status of the most endangered populations" Mammal Rev. 29(1): 35–60. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.1999.00035.x

- ↑ Whitehead, H., Reeves, R. R. & Tyack, P. L. (1999) Science and the conversation, protection, and management of wild cetaceans (eds) J. Mann, R. C. Connor, P.L Tyack & H Whitehead in Cetacean societies : field studies of dolphins and whales. Chicago : University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-50340-2

- ↑ Baker, C. S., Cipriano, F. & Palumbi, S. R. (1996) "Molecular genetic identification of whale and dolphin products from commercial markets in Korea and Japan" Molecular Ecology 5: 671-685

- ↑ "Native Alaskans say oil drilling threatens way of life". BBC News. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- 1 2 Palmer, Brian (11 March 2010). "What Does Whale Taste Like?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ "Greenpeace: Stores, eateries less inclined to offer whale". The Japan Times Online. 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Kershaw, A. P. (1988). Northern environmental disturbances. Boreal Institute for Northern Studies, University of Alberta. p. 67. ISBN 978-091-905869-9.

- ↑ Matsutani, Minoru (September 23, 2009). "Details on how Japan's dolphin catches work". Japan Times. p. 3.

- ↑ Nguyen, Vi (26 November 2010). "Warning over contaminated whale meat as Faroe Islands' killing continues". The Ecologist.

- ↑ McCurry, Justin (2009-09-14). "Dolphin slaughter turns sea red as Japan hunting season returns". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Hall, Kevin G. (2003). "Dolphin meat widely available in Peruvian stores: Despite protected status, 'sea pork' is popular fare". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ↑ Sui, Cindy (2014-04-03). "Why Taiwan's illegal dolphin meat trade thrives". BBC. London. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ↑ イルカの味噌根菜煮 [Dolphin in Miso Vegetable Stew]. Cookpad (in Japanese). 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ↑ Johnston, Eric (September 23, 2009). "Mercury danger in dolphin meat". Japan Times. p. 3.

- ↑ "Eskimo Art, Inuit Art, Canadian Native Artwork, Canadian Aboriginal Artwork". Inuitarteskimoart.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- 1 2 "Canadian Seal Hunt Attacked by PETA". The Port City Post. 2009-06-11. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ↑ "Seal Hunt Facts". Sea Shepherd. Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ↑ 5 Forslag til tiltak Archived 2008-04-16 at the Wayback Machine (Norwegian), Government of Norway, March, 2001

- ↑ Silverstein, p. 34

External links

- When Marine Mammals Become Food New York Times, 27 January 2012.