| Carré d'As IV incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of piracy in Somalia, Operation Atalanta | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Somali pirates | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

France: 1 La Fayette-class frigate[1] 30 commandos[1] Germany: 2 reconnaissance planes[1] |

1 hijacked yacht 7 pirates | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| none |

1 yacht recaptured 1 killed 6 captured | ||||||

On September 2, 2008, the French yacht Carré d'As IV and its two crew were captured in the Gulf of Aden by seven armed Somali pirates, who demanded the release of six pirates captured in the April MY Le Ponant raid and over one million dollars in ransom. On September 16, 2008, on the orders of President Nicolas Sarkozy, French special forces raided and recovered the yacht, rescued the two hostages, killed one pirate, and captured the other six. The pirates were flown to France to stand trial for piracy and related offenses; ultimately, five of them were convicted and sentenced to four to eight years in prison, while a sixth was acquitted. The incident marked the second French counter-piracy commando operation of 2008 (after the recovery of the MY Le Ponant),[1] as well as the first French trial of Somali pirates.

Background

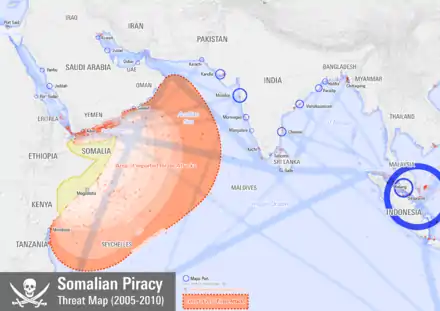

From 2003 to 2007, the number of piracy incidents worldwide declined from 452 to 282; however, piracy increased by 100% in Somalia, which suffered from severe poverty and lacked an effective central government since the 1991 ouster of Siad Barre. By 2005, the International Maritime Bureau advised ships to stay 200 nautical miles off the Somali coast. According to academics J. Ndumbe Anyu and Samuel Moki, "the overwhelming majority of pirates in Somalia come from Puntland, a semi-autonomous region in the northeast of the country... where [Somalia's] poorest of the poor live."[2]: 102–104 By 2008, as Anyu and Moki write, Somalia was the "epicenter of piracy," with 100 ships attacked that year; pirate ransom demands had spiked "from tens of thousands of dollars a few years before to between $500,000 and $3.5 million," since shipowners were willing to pay relatively small amounts to recover much more expensive ships. Pirates extorted about $120 million in ransoms in 2008.[2]: 104 Accordingly, insurance premiums for shipping in the Gulf of Aden increased ten times from 2007 to 2008, from $900 to $9,000.[3] The pirates frequently targeted yachts or commercial ships, which are unarmed and may hold valuable cargo.[2]: 109–110 They sometimes targeted ships bearing humanitarian aid, such as the MV Semlow and MV Miltzow in 2005, which were hijacked while delivering food to Somalia under the UN World Food Programme.[2]: 105 Despite international naval patrols working to curb piracy, The Telegraph noted that the region remained "the most dangerous in the world for pirate attacks," with 24 attacks between April and June 2008.[4] In addition, 94 mariners were captured in the Gulf of Aden in the first half of the year.[3]

On April 4, 2008, pirates seized the 88-meter (289 ft) yacht MY Le Ponant in the Gulf of Aden, capturing 30 crew members. The craft was then moored near Eyl in Puntland, and the owners paid a $2.15 million ransom[5] for the captured crew; the hostages were released unharmed after a week of captivity. The French military captured six suspected pirates and part of the ransom in an April 11 helicopter assault on Jariban, sending the suspects back to France for trial.[1][6] Four of the suspects were later convicted of piracy, while the other two were acquitted.[7] Another pirate attack in the Gulf of Aden occurred 12 days before the assault on the Carré d'As IV, when the Iranian-owned cargo ship MV Iran Deyanat was hijacked on August 21 by 40 pirates and held for 50 days; the ship and its 25 crew were released in November after the IRISL Group allegedly paid $2.5 million in ransom.[8][9]

Pirate hijacking and recovery

_investigate_two_suspected_pirate_skiffs_in_the_Gulf_of_Aden.jpg.webp)

On September 2, 2008, the 16-meter (52 ft), twin-masted[3] yacht Carré d'As IV, which had been sailing from Australia to La Rochelle, France,[10] was attacked and captured by Somali pirates in the Gulf of Aden, where 12 ships had been hijacked since July.[1][4] The pirates, later identified as Ahmed Mahmoud Ahmoud, Sheik Nur Jama Mohamud,[11] Mohamed Hassan Yacub,[11] Abdirahman Farah Awil, Abdulahi Ahmed Guelleh, Ahmed Mohamed Yusuf,[12] and a seventh man,[13][lower-alpha 1] attacked in two speedboats, armed with (defective) rocket launchers, three assault rifles, and ammunition.[14] The yacht's two crew, 60-year old Tahiti residents Jean-Yves and Bernadette Delanne, were taken and held for a ransom of $1–2 million; the pirates also demanded the release of the six pirates captured by the French in April.[1][11] The Delannes, who were seasoned sailors,[15] later recalled that their captors were seasick, unprepared amateurs, and called them "kids out of their depth."[16] The pirates stole various valuables on board, including $1,000 in cash, $900 worth of traveler's checks, a digital camera, and jewelry.[14]

The pirates reportedly then set course for Eyl. Eyl official Abdullahi Saed Yusuf said that "We are powerless to help," while a French military spokesman announced that the French Navy and base at Djibouti were "on standby, ready to intervene."[4] A contradictory report from the East African Seafarers' Assistance Programme stated that the Delannes had been moved to a pirate base in the Xaabo mountains, and that the pirates were using the Carré d'As IV as a "decoy vessel" to attract more victim ships.[3] The couple's daughter, Alizee, claimed on Tahitian radio that she had spoken with her parents on a satellite phone, and that they were "fine".[4] According to another press account, a feud developed between Yacub and the pirates' sponsor, "Shire," a Puntland organized crime figure who belonged to a different clan; on September 12, Yacub sailed for Eyl, prompting a 400-kilometer (250 mi) overland pursuit by Shire's men that ended at Ras Hafun.[17]

On September 15, French President Nicolas Sarkozy ordered a raid when he learned that the pirates were absconding to Eyl. The same night, 30 French Commandos Marine parachuted in[18] and stormed the Carré d'As IV while it was in Somali territorial waters,[14] killing one of the pirates and capturing the six others in under ten minutes. Malaysia and Germany lent support to the mission, the latter contributing two reconnaissance planes. The Delannes were safely rescued, brought aboard the French La Fayette-class frigate Courbet, and taken to Djibouti; after being held for a week, the pirates were flown to Paris, France, for trial.[1][11][16]

Aftermath and trial

In a news conference after the rescue operation, Sarkozy called the raid a "warning" to pirates, declaring that "'France will not allow crime to pay... This operation is a warning to all those who indulge in this criminal activity. This is a call for the mobilization of the international community.'"[1] He also endorsed the creation of a "marine police" unit to ensure security, and further "punitive action" against pirates. A Puntland official supported the French move, urging further international involvement to quell piracy.[1]

In November 2011, after being detained for over three years, the six accused pirates, ranging from the ages of 21 to 36, were charged with "hijacking, kidnapping and armed robbery" in France's first trial of Somali pirates.[11][14] France was the fifth European country to try accused Somali pirates, after Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany.[19] Since Yusuf was below the age of 18 at the time of the hijacking, the trial was held in camera,[15] with an interpreter to assist the defendants.[19]

The Delannes, who testified at the trial, described Yusuf as serving as the cook and Shire's representative, Awil as the sailor, Yacub as an interpreter, Ahmoud as a "warrior," and Guelleh as the fisherman responsible for feeding the pirate and captives.[13][20] Sarkozy's speech was also entered into the trial as evidence.[16] Psychiatrist Jean-Claude Archambault examined the defendants and concluded that Mohamud had developed a mental illness during imprisonment.[21] The prosecution argued that the Somalis, who described themselves as "simple fishermen,"[22] were "dangerous terrorists."[16] Prosecutor Anne Obez-Vosgien requested 14–16 year sentences for Mohamud, Awil, and Ahmoud, a 13–15 year sentence for Yacub, eight years for Yusuf, and six years for Guelleh.[13] The lawyers for the accused took the case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), saying their arrest and transfer was illegal;[16] they also argued that the alleged pirates on trial were scapegoats for "the main culprits".[15] According to Le Monde diplomatique, "the trial revealed that they were just following the orders of a powerful local man [Shire], who was identified but never investigated."[16]

On November 30, after a 15-day trial, five of the accused received sentences between four and eight years, while the 36-year-old Guelleh was acquitted and released.[16] The defendants apologized to the Delannes, who kissed them and wished them "a new and happy life".[11][16] The prosecutor appealed the sentences and acquittal on December 5, arguing they were too lenient.[23] Guelleh, who complained of beatings from fellow inmates and maltreatment while in prison,[16][23] applied for French political asylum in 2012.[24] In December 2014, the ECHR ruled that while the French were permitted to detain suspected pirates, they must be brought before a judge immediately once in France; the ECHR ordered France to pay the 10 hijackers of the Carré d'As IV and the MY Le Ponant €2,000–5,000 in damages.[25]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Except for those cited otherwise, names are reported as given in the November 29, 2011, RFI report. Yusuf (alternatively spelled "Youssouf") is identified by his full name in the November 15 RFI report. The seventh hijacker is not identified.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "French commandos free kidnapped sailors; Couple held for ransom and freedom for 6 prisoners". The Province. Agence France-Presse. September 17, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Anyu, J. Ndumbe; Moki, Samuel (Summer 2009). "The Piracy Hot Spot and Its Implications for Global Security". Mediterranean Quarterly. 20 (3): 95–121. doi:10.1215/10474552-2009-017. S2CID 154957789.

- 1 2 3 4 Costello, Miles (September 11, 2008). "Somalian piracy cripples shipping with tenfold insurance cost rises". The Times.

- 1 2 3 4 "$1million ransom for French couple seized on yacht". The Telegraph. September 5, 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Langewiesche, William (April 2009). "The Pirate Latitudes". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ "France charges Somali 'pirates'". BBC News. April 18, 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Zemmouri, Catherine (June 11, 2013). "The Somali fisherman abducted and abandoned in Paris". BBC News. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Grace, Nick (September 22, 2008). "Mystery surrounds hijacked Iranian ship". Long War Journal. Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Hill, Helen; Smith, Neville (November 14, 2008). "Hijacked Iranian bulker berths at Rotterdam". Lloyd's List. Archived from the original on 2009-01-26. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "Los franceses secuestrados en Somalia por piratas 'están bien', dice su hija". Periodista Digital (in Spanish). EFE. September 5, 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Somali pirates jailed for French kidnapping". The Telegraph. November 30, 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Alexandre, Franck (November 16, 2011). "Levée du huis clos pour le procès des 6 pirates somaliens à la cour d'assises de Paris". Radio France Internationale (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Lourdes peines requises contre les pirates somaliens en France". Radio France Internationale (in French). November 29, 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Jolly, Patricia (November 6, 2011). "L'affaire du 'Carré-d'As', ou le premier procès de pirates somaliens en France". Le Monde (in French).

- 1 2 3 Samuel, Henry (November 15, 2011). "First French trial against Somali pirates opens in Paris". The Telegraph. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Carayol, Rémi (February 2012). "The pirate nobody wants". Le Monde diplomatique. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Alexandre, Franck (November 22, 2011). "Procès du "Carré d'As" : une guerre de clans entre pirates somaliens". Radio France Internationale (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Burleigh, Michael (November 2008). "All at Sea Over Pirates". Standpoint. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- 1 2 Guisnel, Jean (December 1, 2011). "Verdict 'indulgent' pour cinq pirates somaliens du Carré d'As IV". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Procès à Paris des pirates somaliens du Carré d'As: "Ils étaient malades en mer!"". 20 minutes (in French). Agence France-Presse. January 29, 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Pirates somaliens jugés en France: un expert dresse leur profil psychiatrique". Radio France Internationale (in French). November 16, 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "Les pirates somaliens présumés jugés en France se décrivent comme des pêcheurs". Radio France Internationale (in French). November 17, 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- 1 2 Hopquin, Benoît (December 12, 2011). "L'immense solitude de l'acquitté du 'Carré-d'As'". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Hopquin, Benoit (January 22, 2013). "Des Somaliens à Paris". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ "La France condamnée à verser des indemnités à des pirates somaliens". Radio France Internationale (in French). December 5, 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2016.