Roberto Cofresí | |

|---|---|

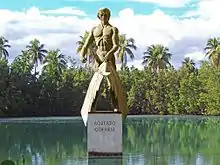

Monument of Roberto Cofresí located in Boquerón Bay. | |

| Born | June 17, 1791 |

| Died | March 29, 1825 (aged 33) San Juan, Captaincy General of Puerto Rico |

| Piratical career | |

| Nickname | El Pirata Cofresí |

| Other names | Cofrecina(s) |

| Type | Caribbean pirate |

| Allegiance | None |

| Rank | Captain |

| Base of operations | Barrio de Pedernales Isla de Mona Vieques |

| Commands | Flotilla of unidentified vessels Caballo Blanco Neptune Anne |

| Battles/wars | Capture of the Anne |

| Wealth | 4,000 pieces of eight (hidden remnants of a larger fortune) |

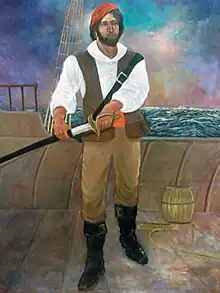

Roberto Cofresí y Ramírez de Arellano[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] (June 17, 1791 – March 29, 1825), better known as El Pirata Cofresí, was a pirate from Puerto Rico. He was born into a noble family, but the political and economic difficulties faced by the island as a colony of the Spanish Empire during the Latin American wars of independence meant that his household was poor. Cofresí worked at sea from an early age which familiarized him with the region's geography, but it provided only a modest salary, and he eventually decided to abandon the sailor's life and became a pirate. He had previous links to land-based criminal activities, but the reason for Cofresí's change of vocation is unknown; historians speculate that he may have worked as a privateer aboard El Scipión, a ship owned by one of his cousins.

At the height of his career, Cofresí evaded capture by vessels from Spain, Gran Colombia, the United Kingdom, Denmark, France, and the United States.[2] He commanded several small-draft vessels, the best known a fast six-gun sloop named Anne, and he had a preference for speed and maneuverability over firepower. He manned them with small, rotating crews which most contemporaneous documents numbered at 10 to 20. He preferred to outrun his pursuers, but his flotilla engaged the West Indies Squadron twice, attacking the schooners USS Grampus and USS Beagle. Most crew members were recruited locally, although men occasionally joined them from the other Antilles, Central America, and Europe. He never confessed to murder, but he reportedly boasted about his crimes, and 300 to 400 people died as a result of his pillaging, mostly foreigners.

Cofresí proved too much for local authorities, who accepted international help to capture the pirate; Spain created an alliance with the West Indies Squadron and the Danish government of Saint Thomas. On March 5, 1825, the alliance set a trap which forced Anne into a naval battle. After 45 minutes, Cofresí abandoned his ship and escaped overland; he was recognized by a resident who ambushed and injured him. Cofresí was captured and imprisoned, making a last unsuccessful attempt to escape by trying to bribe an official with part of a hidden stash. The pirates were sent to San Juan, Puerto Rico, where a brief military tribunal found them guilty and sentenced them to death. On March 29, 1825, Cofresí and most of his crew were executed by firing squad.

He inspired stories and myths after his death, most emphasizing a Robin Hood-like "steal from the rich, give to the poor" philosophy which became associated with him. This portrayal has grown into legend, commonly accepted as fact in Puerto Rico and throughout the West Indies. Some of these claim that Cofresí became part of the Puerto Rican independence movement and other secessionist initiatives, including Simón Bolívar's campaign against Spain. Historical and mythical accounts of his life have inspired songs, poems, plays, books, and films. In Puerto Rico, caves, beaches, and other alleged hideouts or locations of buried treasure have been named after Cofresí, and a resort town is named for him near Puerto Plata in the Dominican Republic.

Early years

Lineage

In 1945, historian Enrique Ramírez Brau speculated that Cofresí may have had Jewish ancestry.[3] A theory, held by David Cuesta and historian Ursula Acosta (a member of the Puerto Rican Genealogy Society), held that the name Kupferstein ("copper stone") may have been chosen by his family when the 18th-century European Jewish population adopted surnames.[3] The theory was later discarded when their research uncovered a complete family tree prepared by Cofresí's cousin, Luigi de Jenner,[4] indicating that their name was spelled Kupferschein (not Kupferstein).[3][5] Originally from Prague, Cofresí paternal patriarch Cristoforo Kupferschein received a recognition and coat of arms from Ferdinand I of Austria in December 1549 and eventually moved to Trieste.[6] His last name was probably adapted from the town of Kufstein.[7] After its arrival, the family became one of Trieste's early settlers.[6] Cristoforo's son Felice was recognized as a noble in 1620, becoming Edler von Kupferschein.[6] The family gained prestige and became one of the city's wealthiest, with the next generation receiving the best possible education and marrying into other influential families.[8] Cofresí's grandfather, Giovanni Giuseppe Stanislao de Kupferschein, held several offices in the police, military and municipal administration.[9] According to Acosta, Cofresí's father Francesco Giuseppe Fortunato von Kupferschein received a lateinschule education and left at age 19 for Frankfurt (probably in search of a university or legal practice).[10] In Frankfurt he mingled with influential figures such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,[11] returning to Trieste two years later.[11]

As a cosmopolitan, mercantile city Trieste was a probable hub of illicit trade,[12] and Francesco was forced to leave after he killed Josephus Steffani on July 31, 1778.[13] Although Steffani's death is commonly attributed to a duel, given their acquaintanceship (both worked at a criminal court) it may have been related to illegal activity.[14] Francesco's name and those of four sailors soon became linked to the murder.[13] Convicted in absentia, the fugitive remained in touch with his family.[15] Francesco went to Barcelona, reportedly learning Spanish there.[15] By 1784 he had settled in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, a harbor town recently separated from the municipality of San Germán and made the seat of an eponymous municipality, where he was accepted by the local aristocracy[16] with the Spanish honorific Don ("of noble origin").[17] Francesco's name was Hispanicized to Francisco José Cofresí (his third given name was not), which was easier for his neighbors to pronounce.[15][18] Since he was linked to illegal commerce in his homeland, he probably relocated to Cabo Rojo for strategic reasons; its harbor was far from San Juan, the capital.[19] Francisco soon met María Germana Ramírez de Arellano y Segarra, and they married. His wife was born to Clemente Ramírez de Arellano y del Toro y Quiñones Rivera, a noble and first cousin of town founder Nicolás Ramírez de Arellano y Martínez de Matos.[14] Her paternal family, descended from the Jimena royal dynasty of the Kingdom of Navarre and the first royal house of the Kingdom of Aragón (said house was established by a Jimena prince), owned a significant amount of land in Cabo Rojo.[20][21] After their marriage the couple settled in El Tujao (or El Tujado), near the coast.[22] Francisco's father Giovanni died in 1789, and a petition pardoning him for Steffani's murder a decade before was granted two years later (enabling him to return to Trieste).[23] However, no evidence exists that Francisco ever returned to the city.[23]

Penniless nobleman and marauder

The Latin American wars of independence had repercussions in Puerto Rico; due to widespread privateering and other naval warfare, maritime commerce suffered heavily.[24] Cabo Rojo was among the municipalities affected most, with its ports at a virtual standstill.[24] African slaves took to the sea in an attempt at freedom;[25] merchants were assessed higher taxes and harassed by foreigners.[24] Under these conditions, Cofresí was born to Francisco and María Germana. The youngest of four children, he had one sister (Juana) and two brothers (Juan Francisco and Juan Ignacio). Cofresí was baptized into the Catholic Church by José de Roxas, the first priest in Cabo Rojo, when he was fifteen days old.[26] María died when Cofresí was four years old, and an aunt assumed his upbringing.[27] Francisco then began a relationship with María Sanabria, the mother of his last child Julián.[28] A don by birth, Cofresí's education was above average;[29] since there is no evidence of a school in Cabo Rojo at that time, Francisco may have educated his children or hired a tutor.[29] The Cofresís, raised in a multicultural environment, probably knew Dutch and Italian.[30][31] In November 1814 Francisco died,[25] leaving a modest estate;[17] Roberto was probably homeless, with no income.[32]

On January 14, 1815, three months after his father's death, Cofresí married Juana Creitoff in San Miguel Arcángel parish, Cabo Rojo.[16][25] Contemporary documents are unclear about her birthplace; although it is also listed as Curaçao, she was probably born in Cabo Rojo to Dutch parents.[33] After their marriage, the couple moved to a residence bought for 50 pesos by Creitoff's father, Geraldo.[25] Months later Cofresí's father in-law lost his humble home in a fire, plunging the family into debt.[34] Three years after his marriage Cofresí owned no property and lived with his mother-in-law, Anna Cordelia.[32][35] He established ties with residents of San Germán, including his brothers-in-law: the wealthy merchant Don Jacobo Ufret and Don Manuel Ufret.[34] The couple struggled to begin a family of their own, conceiving two sons (Juan and Francisco Matías) who died soon after birth.[16]

Although he belonged to a prestigious family, Cofresí was not wealthy.[36] In 1818 he paid 17 maravedís in taxes, spending most of his time at sea and earning a low wage.[34][37] According to historian Walter Cardona Bonet, Cofresí probably worked in a number of fishing corrals in Boquerón Bay.[37] The corrals belonged to the aristocrat Cristóbal Pabón Dávila, a friend of municipal port captain José Mendoza.[38] This connection is believed to have later protected Cofresí, since Mendoza was godfather to several of his brother Juan Francisco's children.[38] The following year he first appeared on a government registry as a sailor,[37] and there is no evidence linking him to any other jobs in Cabo Rojo.[39] Although Cofresí's brothers were maritime merchants and sailed a boat, Avispa, he probably worked as an able fisherman.[40] On December 28, 1819, Cofresí was registered on Ramona, ferrying goods between the southern municipalities.[35] In addition, her frequent voyages to the Mona Passage and Cofresí's recognition by local residents indicate that he occasionally accompanied Avispa[41] That year, Cofresí and Juana lived in Barrio del Pueblo and paid higher taxes than the previous year: five reales.[34]

Political changes in Spain affected Puerto Rico's stability during the first two decades of the 19th century.[42] Europeans and refugees from the American colonies began arriving after the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815, changing the archipelago's economic and political environments.[42] With strategic acquisitions, the new arrivals triggered a rise in prices.[43] Food distribution was inefficient, particularly in non-agricultural areas.[44] Unmotivated and desperate, the local population drifted toward crime and dissipation.[42] By 1816, governor Salvador Meléndez Bruna shifted responsibility for law enforcement from the Captaincy General of Puerto Rico to the mayors.[42] Driven by hunger and poverty, highway robbers continued to roam southern and central Puerto Rico.[44] In 1817 wealthy San Germán residents requested help with the criminals, who were invading houses and shops.[45] The following year, Meléndez established a high-security prison at El Arsenal in San Juan.[44] During the next few years, the governor transferred repeat offenders to San Juan.[44] Cabo Rojo, with its high crime rate,[43] also dealt with civil strife, inefficient law enforcement and corrupt officials.[43] While he was still a don, Cofresí led a criminal gang in San Germán which stole cattle, food and crops.[46] He was linked to an organization operating near the Hormigueros barrio since at least 1818 and to another nobleman, Juan Geraldo Bey.[46] Among Cofresí's associates were Juan de los Reyes, José Cartagena and Francisco Ramos,[44] and the criminals continued to thrive in 1820.[45] The situation worsened with the arrival of unauthorized street vendors from nearby municipalities, who were soon robbed.[45] A series of storms and droughts drove residents away from Cabo Rojo, worsening the already-poor economy;[45] authorities retrained the unemployed and underemployed as night watchmen.[43]

The regional harvest was destroyed by a September 28, 1820, hurricane, triggering the region's largest crime wave to date.[47] Newly appointed Puerto Rican governor Gonzalo Aróstegui Herrera immediately ordered Lieutenant Antonio Ordóñez to round up as many criminals as possible.[47] On November 22, 1820, a group of fifteen men from Cabo Rojo participated in the highway robbery of Francisco de Rivera, Nicolás Valdés and Francisco Lamboy on the outskirts of Yauco.[47] Cofresí is believed to have been involved in this incident because of its timing and the criminals' link to an area headed by his friend, Cristóbal Pabón Dávila.[48] The incident sparked an uproar in towns throughout the region, and convinced the governor that the authorities were conspiring with the criminals.[49] Among measures taken by Aróstegui were a mayoral election in Cabo Rojo (Juan Evangelista Ramírez de Arellano, one of Cofresí's relatives, was elected) and an investigation of the former mayor.[50] The incoming mayor was ordered to control crime in the region, an unrealistic demand with the resources at his disposal.[50] Bernardo Pabón Davila, a friend of Cofresí and relative of Cristóbal, was assigned to prosecute the Yauco incident.[51] Bernardo reportedly protected the accused and argued against pursuing the case, saying that according to "private confidences" they were fleeing to the United States.[51] Other initiatives to capture highway robbers in Cabo Rojo were more successful, resulting in over a dozen arrests;[52] among them was the nobleman Bey, who was charged with murder.[53] Known as "El Holandés", Bey testified that Cofresí led a criminal gang.[51] Cofresí's primary collaborators were the Ramírez de Arellano family, who prevented his capture[54] as Cabo Rojo's founding family with high positions in politics and law enforcement.[54] The central government issued wanted posters for Cofresí,[54] and in July 1821 he and the rest of his gang were captured;[51] Bey escaped, becoming a fugitive.[51] Cofresí and his men were tried in San Germán's courthouse, where their connection to several crimes was proven.[51]

On August 17, 1821 (while Cofresí was in prison) Juana gave birth to their only daughter, Bernardina.[16][55][56] Due to his noble status, Cofresí probably received a pass for the birth[55] and took the opportunity to escape;[55] in alternative theories, he broke out or was released on parole.[55] While Cofresí was a fugitive, Bernardo Pabón Davila was Bernardina's godfather and Felícita Asencio her godmother.[57][58] On December 4, 1821, a wanted poster was circulated by San Germán mayor Pascacio Cardona.[59] There is little documentation of Cofresí's whereabouts in 1822.[60] Historians have suggested that he exploited his upper-class connections to remain concealed;[61] the Ramírez de Arellano family held most regional public offices, and their influence extended beyond the region.[61] Other wealthy families, including the Beys, had similarly protected their relatives and Cofresí may have hidden in plain sight due to the inertia of Cabo Rojo authorities.[61] When he became a wanted man, he moved Juana and Anna to her brothers' houses and would visit in secret;[62] Juana also visited him at his headquarters in the rural ward of Pedernales in Cabo Rojo.[62] It is unknown how far Cofresí traveled during this time, but he had associates on the east coast and may have taken advantage of eastern migration from Cabo Rojo.[63] Although he may have been captured and imprisoned in San Juan, he does not appear in contemporary records.[60] However, Cofresí's associates Juan "El Indio" de los Reyes, Francisco Ramos and José "Pepe" Cartagena were released only months before his recorded reappearance.[60]

"Last of the West India pirates"

Establishing a reputation

By 1823 Cofresí was probably on the crew of the corsair barquentine El Scipión, captained by José Ramón Torres and managed by his cousin (the first mayor of Mayagüez, José María Ramírez de Arellano).[nb 1][33][65] Historians agree, since several of his friends and family members benefited from the sale of stolen goods.[66] Cofresí may have joined to evade the authorities, honing skills he would use later in life.[66] El Scipión employed questionable tactics later associated with the pirate, such as flying the flag of Gran Colombia so other ships would lower their guard (as she did in capturing the British frigate Aurora and the American brigantine Otter).[67] The capture of Otter led to a court order requiring restitution, affecting the crew.[68] At this time, Cofresí turned to piracy.[69] Although the reasons behind his decision are unclear, several theories have been proposed by researchers.[69] In Orígenes portorriqueños Ramírez Brau speculates that Cofresí's time aboard El Scipión, or seeing a family member become a privateer, may have influenced his decision to become a pirate[33] after the crew's pay was threatened by the lawsuit. According to Acosta, a lack of work for privateers ultimately pushed Cofresí into piracy.[69]

The timing of this decision was crucial in establishing him as the dominant Caribbean pirate of the era. Cofresí began his new career in early 1823, filling a role vacant in the Spanish Main since the death of Jean Lafitte, and was the last major target of West Indies anti-piracy operations. While piracy was heavily monitored and most pirates were rarely successful, Cofresí was confirmed to have plundered at least eight vessels and has been credited with over 70 captures.[70] Unlike his predecessors, Cofresí is not known to have imposed a pirate code on his crew; his leadership was enhanced by an audacious personality, a trait acknowledged even by his pursuers. According to 19th-century reports he had a rule of engagement that when a vessel was captured, only those willing to join his crew were permitted to live. Cofresí's influence extended to a large number of civil informants and associates, forming a network which took 14 years after his death to fully dismantle.

The earliest document linked to Cofresí's modus operandi is a letter dated July 5, 1823, from Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, which was published in the St. Thomas Gazette.[71] The letter reported that a brigantine, loaded with coffee and West Indian indigo from La Guaira, was boarded by pirates on June 12.[71] The hijackers ordered the ship brought to Isla de Mona (incorrectly anglicized as "Monkey Island"), a small island in the eponymous passage between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola,[72][73] where its captain and crew were ordered to unload the cargo.[71] After this was done, the pirates reportedly killed the sailors and sank the brigantine.[71] Both of Cofresí's brothers were soon involved in his operation, helping him move plunder and deal with captured ships.[41] Juan Francisco was able to gather information about maritime traffic in his work at the port, presumably forwarding it to his brother.[38] The pirates communicated with their cohorts through coastal signs, and their associates on land warned them of danger;[74] the system was probably used to identify loaded vessels as well.[75] According to Puerto Rican historian Aurelio Tió, Cofresí shared his loot with the needy (especially family members and close friends) and was considered the Puerto Rican equivalent of Robin Hood.[56] Acosta disagrees, saying that any acts of generosity were probably opportunistic.[76] Cardona Bonet's research suggests that Cofresí organized improvised markets in Cabo Rojo, where plunder would be informally sold;[77] according to this theory, merchant families would buy goods for resale to the public.[77] The process was facilitated by local collaborators, such as French smuggler Juan Bautista Buyé.[78]

On October 28, 1823, months after the El Scipión case was settled, Cofresí attacked a ship registered to the harbor of Patillas[79] and robbed the small fishing boat of 800 pesos in cash.[79] Cofresí attacked with other members of his gang and that of another pirate, Manuel Lamparo, who was connected to British pirate Samuel McMorren (also known as Juan Bron).[80] That week he also led the capture of John, an American schooner. Out of Newburyport and captained by Daniel Knight, on its way to Mayagüez the ship was intercepted by a ten-ton schooner armed with a swivel gun near Desecheo Island.[81] Cofresí's group, consisting of seven pirates armed with sabers and muskets, stole $1,000 in cash, tobacco, tar and other provisions and the vessel's square rig and mainsail.[81] Cofresí ordered the crew to head for Santo Domingo, threatening to kill everyone aboard if they were seen at any Puerto Rican port.[81] Despite the threat, Knight went to Mayagüez and reported the incident.[81]

It was soon established that some of the pirates were from Cabo Rojo, since they disembarked there.[82] Undercover agents were sent to the town to track them, and new mayor Juan Font y Soler requested resources to deal with a larger group which was out of control.[82] Links between the pirates and local sympathizers made arresting them difficult.[82] The central government, frustrated with Cabo Rojo's inefficiency, demanded the pirates' capture[83] and western Puerto Rico military commander José Rivas was ordered to exert pressure on local authorities.[83] Although Cofresí was tracked to the beach in Peñones, near his brothers' homes in Guaniquilla, the operation only recovered the John's sails, meat, flour, cheese, lard, butter and candles;[83] the pirates escaped aboard a schooner.[84] A detachment caught Juan José Mateu and charged him with conspiracy;[80] his confession linked Cofresí to the two hijackings.[80]

Cofresí's sudden success was an oddity, nearly a century after the end of the Golden Age of Piracy. By this time, joint governmental efforts had eradicated rampant buccaneering by Anglo-French seamen (primarily based on Jamaica and Tortuga), which had turned the Caribbean into a haven for pirates attacking shipments from the region's Spanish colonies; this made his capture a priority. By late 1823, the pursuit on land probably forced Cofresí to move his main base of operations to Mona; the following year, he was often there.[72] This base, initially a temporary haven with Barrio Pedernales his stable outpost, became more heavily used.[72] Easily accessible from Cabo Rojo, Mona had been associated with pirates for more than a century; it was visited by William Kidd, who landed in 1699 after fleeing with a load of gold, silver and iron.[85] A second pirate base was found at Saona, an island south of Hispaniola.[86]

In November a number of sailors aboard El Scipión took advantage of her officers' shore leave and mutinied, seizing control of the ship.[87] The vessel, repurposed as a pirate ship, began operating in the Mona Passage and was later seen at Mayagüez before disappearing from the record.[68] Cofresí was linked to El Scipión by pirate Jaime Márquez, who admitted under police questioning on Saint Thomas that boatswain Manuel Reyes Paz was a Cofresí associate.[88] The confession hints that the ship was captured by Hispaniola authorities.[88] Cofresí is recorded in eastern Hispaniola (then part of the unified Republic of Haiti, modern-day Dominican Republic), where his crew reportedly rested off Puerto Plata province.[89] On one excursion, the pirates were intercepted by Spanish patrol boats off the coast of Samaná Province.[90] With no apparent escape route, Cofresí is said to have ordered the vessel's sinking and it sailed into Bahía de Samaná before coming to rest near the town of Punta Gorda.[90] This created a diversion, allowing him and his crew to escape in skiffs they rowed to shore and adjacent wetlands (where the larger Spanish ships could not follow).[90] The remains of the ship, reportedly full of plunder, have not been found.[90]

In an article in the May 9, 1936, issue of Puerto Rico Ilustrado, Eugenio Astol described an 1823 incident between Cofresí and Puerto Rican physician and politician Pedro Gerónimo Goyco.[91] The 15-year-old Goyco traveled alone on a schooner to a Santo Domingo school for his secondary education.[91] In mid-voyage, Cofresí intercepted the ship and the pirates boarded it.[91] Cofresí assembled the passengers, asking their names and those of their parents.[91] When he learned that Goyco was among them, the pirate ordered a change of course; they landed on a beach near Mayagüez,[91] where Goyco was freed. Cofresí explained that he knew Goyco's father, an immigrant from Herceg Novi named Gerónimo Goicovich who had settled in Mayagüez.[91] Goyco returned home safely, later attempting the voyage again. The elder Goicovich had favored members of Cofresí's family, despite their association with a pirate.[91] Goyco grew up to become a militant abolitionist, similar to Ramón Emeterio Betances and Segundo Ruiz Belvis.[91]

.jpg.webp)

Cofresí's actions quickly gained the attention of the Anglo-American nations, who called him "Cofrecinas" (a mistranslated, onomatopoeic variant of his last name).[92] Commercial agent and US Consul Judah Lord wrote to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, describing the El Scipión situation and the capture of John.[93] Adams relayed the information to Commodore David Porter, leader of the anti-piracy West Indies Squadron, who sent several ships to Puerto Rico.[93] On November 27 Cofresí sailed from his base on Mona with two sloops (armed with pivot gun cannons) and assaulted another American ship, the brigantine William Henry.[86] The Salem Gazette reported that the following month a schooner sailed from Santo Domingo to Saona, capturing 18 pirates (including Manuel Reyes Paz) and a "considerable quantity" of leather, coffee, indigo, and cash.[94]

International manhunt

Cofresí's victims were locals and foreigners, and the region was economically destabilized. When he boarded Spanish vessels he usually targeted immigrants brought by the royal decree of 1815, ignoring his fellow criollos.[95] The situation was complicated by several factors, most of them geopolitical. The Spanish Empire had lost most of its possessions in the New World, and her last two territories (Puerto Rico and Cuba) faced economic problems and political unrest. To undermine the commerce of former colonies, Spain stopped issuing letters of marque; this left sailors unemployed, and they gravitated towards Cofresí and piracy.[96][97] On the diplomatic front, the pirates assaulted foreign ships while flying the Flag of Spain (angering nations who had reached an agreement about the return of ships captured by corsairs and compensation for losses).[98] Aware that the problem had developed international overtones, Spanish-appointed governor of Puerto Rico Lt. Gen. Miguel Luciano de la Torre y Pando (1822–1837) made Cofresí's capture a priority.[98] By December 1823 other nations joined the effort to combat Cofresí, sending warships to the Mona Passage.[99] Gran Colombia sent two corvettes, Bocayá and Bolívar, under the command of former privateer and Jean Lafitte associate Renato Beluche.[99] The British assigned the brig-sloop HMS Scout to the region after the William Henry incident.[100]

On January 23, 1824, de la Torre implemented anti-piracy measures in response to Spanish losses and political pressure from the United States,[101][102] ordering that pirates be tried in a military tribunal with the defendants considered enemy combatants.[103] De la Torre ordered the pursuit of pirates, bandits, and those aiding them,[104] issuing medals, certificates and bounties in gold and silver as rewards.[105] Manuel Lamparo was captured on Puerto Rico's east coast,[104] and some of his crew joined Cofresí and other fugitives.[104]

United States Secretary of the Navy Samuel L. Southard ordered David Porter to assign ships to the Mona Passage, and the commodore sent the schooner USS Weasel and the brigantine USS Spark.[94] The ships were to investigate the zone, gathering information at Saint Barthélemy and St. Thomas with the goal of destroying the base at Mona.[94] Although Porter warned that the pirates were reportedly well-armed and -supplied, he said the crews would probably not find plunder at the base because of the proximity of eastern Puerto Rican ports.[106] On February 8, 1824, the Spark arrived at Mona, conducted reconnaissance and landed.[106] A suspicious schooner was seen, but captain John T. Newton decided not to chase her.[106] The crew found a small settlement with an empty hut and other buildings, a chest of medicine, sails, books, an anchor and documents from William Henry.[106] Newton ordered the base and a large canoe found in the vicinity destroyed,[64][106] and reported his findings to the Secretary of the Navy.[106] According to another report, the ship sent was the USS Beagle;[85] in this account, several pirates eluded the Beagle's crew.[85] Undeterred, Cofresí quickly resettled on Mona.[64]

Attacks on two brigantines were reported by Renato Beluche on February 12, 1824, and published in El Colombiano several days later.[97] The first was Boniton, captained by Alexander Murdock, which sailed with a load of cocoa from Trinidad and was intercepted en route to Gibraltar.[97] The second, Bonne Sophie, sailed from Havre de Grace under the command of a man named Chevanche with dry goods bound for Martinique.[97] In both cases, the sailors were beaten and imprisoned and the ships plundered.[107] The ships were part of a convoy escorted by the Bolívar off Puerto Real, Cabo Rojo,[108] and Cofresí captained a ship identified by Beluche as a pailebot (a small schooner).[nb 2][109] Although Bolívar could not capture her, her crew described the vessel as painted black, armed with a rotating cannon and having a crew of twenty unidentified Puerto Rican men.[107] Cofresí was presumably leading the vessels to dock at Pedernales, where Mendoza and his brother could facilitate the distribution of loot with the aid of official inertia.[97] From there, other associates usually used Boquerón Bay for transportation and ensured that the loot reached stores in Cabo Rojo and nearby towns.[97]

In this region Cofresí's influence extended to government and the military, with the Ramírez de Arellano family involved in the smuggling and sale of his loot.[54] On land the loot, hidden in sacks and barrels, was brought to Mayagüez, Hormigueros or San Germán for distribution.[54] When Beluche returned to Colombia, he published an article critical of the situation in the press.[97] La Gaceta de Puerto Rico countered, accusing him of stealing Bonne Sophie and connecting him to the pirates.[nb 3][110]

On February 16, 1824, de la Torre mandated a more-aggressive pursuit and prosecution of pirates.[110] In March the governor ordered a search for the schooner Caballo Blanco, reportedly used in the boarding of Boniton and Bonne Sophie and similar attacks.[nb 4][98] In private communication with Mayagüez military commander José Rivas, he asked Rivas to find someone trustworthy who could launch a mission to capture "the so-called Cofresin"[98] and to notify him personally of the pirate's arrest.[98] Authorizing the use of force, the governor described Cofresí as "one of the evil ones that I am pursuing" and acknowledged that the pirate was protected by Cabo Rojo authorities.[98] The mayor was unable (or unwilling) to cooperate, despite orders from de la Torre.[98] Rivas tracked Cofresí to his house twice, but found it empty.[111] When the captain lost contact with the pirate and his wife, he was also unable to communicate with the mayor.[111] A similar search was undertaken in San Germán, whose mayor reported to de la Torre on March 12, 1824.[111]

Martinique governor François-Xavier Donzelot wrote to de la Torre on March 22, concerned about the capture of Bonne Sophie and the impact of piracy on maritime commerce.[112] This brought France into the search for Cofresí;[112] on March 23 de la Torre authorized France to patrol the Puerto Rican coast and commissioned a frigate, Flora.[112] The mission was led by a military commander named Mallet, who was ordered to the west coast and pursue the pirates "until he [was] able to trap and destroy them".[112] Although Flora arrived three days after the operation's approval,[113] the attempt was unsuccessful. Rivas then assigned Joaquín Arroyo, a retired Pedernales militiaman, to monitor activity near Cofresí's house.[114]

In April 1824, Rincón mayor Pedro García authorized the sale of a vessel owned by Juan Bautista de Salas to Pedro Ramírez.[115] Ramírez, who may have been a member of the Ramírez de Arellano family, lived in Pedernales and was a neighbor of Cofresí's brothers and Cristobal Pabón Davila.[115] On April 30, shortly after acquiring the ship, Ramírez sold it to Cofresí (who used it as a pirate flagship).[115] The irregularity of the transactions was quickly noticed, prompting an investigation of García.[116] The scandal weakened his already-frail authority, and Matías Conchuela intervened as the governor's representative.[116] De la Torre asked the mayor of Añasco, Thomás de la Concha, to retrieve the records and verify their accuracy.[116] The investigation, led by public prosecutor José Madrazo of the Regimiento de Granada's Military Anti-Piracy Commission, concluded with Bautista's imprisonment and sanctions for García.[117] Several members of the Ramírez de Arellano family were prosecuted, including the former mayors of Añasco and Mayagüez (Manuel and José María), Tómas and Antonio.[117] Others with the same last name but unclear parentage, such as Juan Lorenzo Ramirez, were also linked to Cofresí.[117]

A number of unsuccessful searches were carried out in Cabo Rojo by an urban militia led by Captain Carlos de Espada,[118] and additional searches were made in San Germán.[118] On May 23, 1824, the Mayagüez military commander prepared two vessels and sent them to Pedernales in response to reported sightings of Cofresí.[119] Rivas and the military captain of Mayagüez, Cayetano Castillo y Picado, boarded a ship commanded by Sergeant Sebastián Bausá.[119] Sailor Pedro Alacán, best known as the grandfather of Ramón Emeterio Betances and a neighbor of Cofresí,[120] was captain of the second schooner.[119] The expedition failed, only finding a military deserter named Manuel Fernández de Córdova.[121] Also known as Manuel Navarro, Fernández was connected to Cofresí through Lucas Branstan (a merchant from Trieste who was involved in Bonne Sophie incident).[121] In the meantime, the pirates fled toward southern Puerto Rico.[122] Poorly supplied after his hasty retreat, Cofresí docked at Jobos Bay on June 2, 1824;[122] about a dozen pirates invaded the hacienda of Francisco Antonio Ortiz, stealing his cattle.[122] The group then broke into a second estate, owned by Jacinto Texidor, stole plantains and resupplied their ship.[122] It is now believed that Juan José Mateu gave the pirates refuge in one of his haciendas, near Jobos Bay.[80] The next day the news reached Guayama mayor Francisco Brenes, who quickly contacted the military and requested operations by land and sea.[122] He was told that there were not enough weapons in the municipality for a mission of that scale. Brenes then requested supplies from Patillas,[122] which rushed him twenty guns.[123]

However, the pirates fled the municipality and traveled west.[124] On June 9, 1824, Cofresí led an assault on the schooner San José y Las Animas off the coast of Tallaboa in Peñuelas.[124] The ship was en route between Saint Thomas and Guayanilla with over 6,000 pesos' worth of dry goods for Félix and Miguel Mattei, who were aboard.[114] The Mattei brothers are now thought to have been anti-establishment smugglers related to Henri La Fayette Villaume Ducoudray Holstein and the Ducoudray Holstein Expedition.[114] The schooner, owned by Santos Lucca, sailed with captain Francisco Ocasio and a crew of four.[125] Frequently used to transport cargo throughout the southern region and Saint Thomas, she made several trips to Cabo Rojo.[125] When Cofresí began the chase, Ocasio headed landward; the brothers abandoned ship and swam ashore, from where they watched the ship's plundering.[124] Portugués was second-in-command during the boarding of San José y las Animas, and Joaquín "El Campechano" Hernández was a crew member.[73][126][127] The pirates took most of the merchandise, leaving goods valued at 418 pesos, three reales and 26 maravedi.[124] Governor Miguel de la Torre was visiting nearby municipalities at the time, which occupied the authorities.[128] Cargo from San José y Las Animas (clothing belonging to the brothers and a painting) was later found at Cabo Rojo.[128] Days later, a sloop and a small boat commanded by Luis Sánchez and Francisco Guilfuchi left Guayama in search of Cofresí.[123] Unable to find him, they returned on June 19, 1824.[129] Patillas and Guayama enacted measures, monitored by the governor, which were intended to prevent further visits.[130]

De la Torre continued his tour of the municipalities, ordering Rivas to focus on the Cabo Rojo area when he reached Mayagüez.[131] The task was given to Lieutenant Antonio Madrona, leader of the Mayagüez garrison.[131] Madrona assembled troops and left for Cabo Rojo, launching an operation on June 17 which ended with the arrest of pirate Eustaquio Ventura de Luciano at the home of Juan Francisco.[132] The troops came close to capturing a second associate, Joaquín "El Maracaybero" Gómez.[133] Madrona then began a surprise attack at Pedernales,[131] finding Cofresí and several associates (including Juan Bey, his brother Ignacio and his brother-in-law Juan Francisco Creitoff).[131] The pirates' only option was to flee on foot.[131] The Cofresí brothers escaped, but Creitoff and Bey were captured and tried in San Germán.[131] Troops later visited Creitoff's house, where they found Cofresí's wife and mother-in-law.[132] Under questioning, the women confirmed the brothers' identities.[133] The authorities continued searching the homes of those involved and those of their families, where they found quantities of plunder hidden and prepared for sale.[132] Madrona also found burned loot on a nearby hill.[132] Juan Francisco Cofresí, Ventura de Luciano and Creitoff were sent to San Juan with other suspected associates.[133] Of this group the pirate's brother, Luis de Río and Juan Bautista Buyé were prosecuted as accomplices instead of pirates.[134] Ignacio was later arrested and also charged as an accomplice.[134] The Mattei brothers filed a claim against shopkeeper Francisco Betances that some of his merchandise was cargo from San José y Las Animas.[134]

In response to a tip, José Mendoza and Rivas organized an expedition to Mona.[135] On June 22, 1824, Pedro Alacán assembled a party of eight volunteers (among them Joaquín Arroyo, possibly Mendoza's source).[120][135] He loaned a small sailboat he co-owned (Avispa, once used by Cofresí's brothers) to José Pérez Mendoza and Antonio Gueyh.[40] There were eight volunteers, The locally coordinated operation intended to ambush and apprehend Cofresí in his hideout.[120] The expedition left the coast of Cabo Rojo with Action Stations in place.[120] Despite unfavorable sea conditions, the party arrived at their destination.[120] However, as soon as they disembarked Avispa was lost.[136] Although most of the pirates were captured without incident, Cofresí's second in-command Juan Portugués was shot to death in the back[136] and dismembered by crewmember Lorenzo Camareno.[126] Among the captives was a man identified as José Rodríguez,[137] but Cofresí was not with his crew.[120] Five days later, they returned to Cabo Rojo on a ship confiscated from the pirates with weapons, three prisoners and Portugués' head and right hand (probably for identification when claiming the bounty).[136] Rivas contacted de la Torre, informing him of further measures to track the pirates.[136] The governor publicized the expedition, writing an account which was published in the government newspaper La Gaceta del Gobierno de Puerto Rico on July 9, 1824.[138] Alacán was honored by the Spanish government, receiving the ship recovered from the pirates as compensation for the loss of the Avispa.[120][139] Mendoza and the crew were also honored.[140] Cofresí reportedly escaped in one of his ships with "Campechano" Hernández, resuming his attacks soon after the ambush.[140][141]

Shortly after the Mona expedition, Ponce mayor José Ortíz de la Renta began his own search for Cofresí.[142] On June 30, 1824, the schooner Unión left with 42 sailors commanded by captain Francisco Francheschi.[142] After three days, the search was abandoned and the ship returned to Ponce.[142] The governor enacted more measures to capture the pirates, including the commission of gunboats.[142] De la Torre ordered the destruction of any hut or abandoned ship which might aid Cofresí in his escape attempts, an initiative carried out on the coasts of several municipalities.[142] Again acting on the basis of information obtained by interrogation, the authorities tracked the pirates during the first week of July.[143] Although José "Pepe" Cartagena (a local mulatto) and Juan Geraldo Bey were found in Cabo Rojo and San Germán respectively, Cofresí avoided the troops.[143] On July 6, 1824, Cartagena resisted arrest and was killed in a shootout,[143] with the developments again featured in La Gaceta del Gobierno de Puerto Rico.[144] During the next few weeks, a joint initiative by Rivas and the west coast mayors led to the arrest of Cofresí associates Gregorio del Rosario, Miguel Hernández, Felipe Carnero, José Rodríguez, Gómez, Roberto Francisco Reifles, Sebastián Gallardo, Francisco Ramos, José Vicente and a slave of Juan Nicolás Bey (Juan Geraldo's father) known as Pablo.[144][145][146] However, the pirate again evaded the net. In his confession, Pablo testified that Juan Geraldo Bey was an accomplice of Cofresí.[146] Sebastián Gallardo was captured on July 13, 1824, and tried as a collaborator.[147] The defendants were transported to San Juan, where they were prosecuted by Madrazo in a military tribunal overseen by the governor.[148] The trial was plagued by irregularities, including Gómez' allegation that the public attorney had accepted a bribe of 300 pesos from Juan Francisco.[148]

During the searches, the pirates stole a "sturdy, copper-plated boat" from Cabo Rojo and escaped.[149] The ship was originally stolen in San Juan by Gregorio Pereza and Francisco Pérez (both arrested during the search for Caballo Blanco) and given to Cofresí.[150] When the news became public, mayor José María Hurtado asked local residents for help.[149] On August 5, 1824, Antonio de Irizarry found the boat at Punta Arenas, a cape in the Joyuda barrio.[149] The mayor quickly organized his troops, reaching the location on horseback.[149] Aboard the ship they found three rifles, three guns, a carbine, a cannon, ammunition and supplies.[151] After an unsuccessful search of nearby woods, the mayor sailed the craft to Pedernales and turned it over to Mendoza.[152] A group left behind continued the search, but did not find anyone.[152] Assuming that the pirates had fled inland, Hurtado alerted his colleagues in the region about the find.[152] The mayor resumed the search, but abandoned it due to a rainstorm and poor directions.[152] Peraza, Pérez, José Rivas del Mar, José María Correa and José Antonio Martinez were later arrested, but Cofresí remained free.[150]

On August 5, 1824, the pirate and a skeleton crew captured the sloop María off the coast of Guayama[153] as she completed a run between Guayanilla and Ponce under the command of Juan Camino.[153] After boarding the ship they decided not to plunder her, since a larger craft was sailing towards them.[153] The pirates fled west, intercepting a second sloop (La Voladora) off Morillos.[153] Cofresí did not plunder her either, instead requesting information from captain Rafael Mola.[153] That month a ship commanded by the pirates stalked the port of Fajardo, taking advantage of the lack of gunboats capable of pursuing their shallow-draft vessels.[154] Shortly afterwards, the United States ordered captain Charles Boarman of the USS Weasel to monitor the western waters of Puerto Rico as part of an international force.[154] The schooner located a sloop commanded by the pirates off Culebra, but it fled to Vieques and ran inland into dense vegetation;[154] Boarman could only recover the ship.[154]

The Danish sloop Jordenxiold was intercepted off Isla Palominos on September 3, 1824, as she completed a voyage from Saint Thomas to Fajardo;[155] the pirates stole goods and cash from the passengers.[155] The incident attracted the attention of the Danish government, which commissioned the Santa Cruz (a 16-gun brigantine commanded by Michael Klariman) to monitor the areas off Vieques and Culebra.[155] On September 8–9 a hurricane Nuestra Señora de la Monserrate, struck southern Puerto Rico and passed directly over the Mona Passage.[102][156] Cofresí and his crew were caught in the storm, which drove their ship towards Hispaniola.[102] According to historian Enrique Ramírez Brau, an expedition weeks later by Fajardo commander Ramón Aboy to search Vieques, Culebra and the Windward Islands for pirates was actually after Cofresí.[102] The operation used the schooner Aurora (owned by Nicolás Márquez) and Flor de Mayo, owned by José María Marujo.[102] After weeks of searching, the team failed to locate anything of interest.[102]

Continuing to drift, Cofresí and his crew were captured after his ship reached Santo Domingo. Sentenced to six years in prison, they were sent to a keep named Torre del Homenaje.[157] Cofresí and his men escaped, were recaptured and again imprisoned. The group escaped again, breaking the locks on their cell doors and climbing down the prison walls on a stormy night on a rope made from their clothing.[157] With Cofresí were two other inmates: a man known as Portalatín and Manuel Reyes Paz, former boatswain of El Scipión.[102] After reaching the province of San Pedro de Macorís, the pirates bought a ship.[156] They sailed from Hispaniola in late September to Naguabo, where Portalatín disembarked.[155] From there they went to the island of Vieques, where they set up another hideout and regrouped.

Challenge to the West Indies Squadron

By October 1824 piracy in the region was dramatically reduced, with Cofresí the remaining target of concern.[158] However, that month Peraza, Pérez, Hernández, Gallardo, José Rodríguez and Ramos escaped from jail.[150] Three former members of Lamparo's crew—a man of African descent named Bibián Hernández Morales, Antonio del Castillo and Juan Manuel de Fuentes Rodríguez—also broke out.[150] They were joined by Juan Manuel "Venado" de Fuentes Rodríguez, Ignacio Cabrera, Miguel de la Cruz, Damasio Arroyo, Miguel "El Rasgado" de la Rosa and Juan Reyes.[159] Those traveling east met with Cofresí, who welcomed them on his crew; the pirate was in Naguabo looking for recruits after his return from Hispaniola.[160] Hernández Morales, an experienced knife fighter, was second-in-command of the new crew.[147][161] At the height of their success, they had a flotilla of three sloops and a schooner.[162] The group avoided capture by hiding in Ceiba, Fajardo, Naguabo, Jobos Bay and Vieques,[160] and when Cofresí sailed the east coast he reportedly flew the flag of Gran Colombia.[155]

On October 24, Hernández Morales led a group of six pirates in the robbery of Cabot, Bailey & Company in Saint Thomas, making off with US$5,000.[163] On October 26 the USS Beagle, commanded by Charles T. Platt, navigated by John Low and carrying shopkeeper George Bedford (with a list of plundered goods, which were reportedly near Naguabo) left Saint Thomas.[163] Platt sailed to Vieques, following a tip about a pirate sloop.[163] Beagle opened fire, interrupting the capture of a sloop from Saint Croix, but the pirates docked at Punta Arenas in Vieques and fled inland; one, identified as Juan Felis, was captured after a shootout.[164] When Platt disembarked in Fajardo to contact Juan Campos, a local associate of Bedford, the authorities accused him of piracy and detained him.[164] The officer was later freed, but the pirates escaped.[165] Commodore Porter's reaction to what was later known as the Fajardo Affair led to a diplomatic crisis which threatened war between Spain and the United States; Campos was later found to be involved in the distribution of loot.[166]

With more ships, Cofresí's activity near Culebra and Vieques peaked by November 1824.[100] The international force reacted by sending more warships to patrol the zone; France provided the Gazelle, a brigantine, and the frigate Constancia.[100] After the Fajardo incident the United States increased its flotilla in the region, with the USS Beagle joined by the schooners USS Grampus and USS Shark in addition to the previously commissioned Santa Cruz and Scout.[100] Despite unprecedented monitoring, Cofresí grew bolder. John D. Sloat, captain of Grampus, received intelligence placing the pirates in a schooner out of Cabo Rojo.[75] On the evening of January 25, 1825, Cofresí sailed a sloop towards Grampus, which was patrolling the west coast.[75] In position, the pirate commanded his crew (armed with sabers and muskets) to open fire and ordered the schooner to stop.[75] When Sloat gave the order to counterattack, Cofresí sailed into the night.[75] Although a skiff and cutters from Grampus were sent after the pirates, they failed to find them after a two-hour search.[167]

The pirates sailed east and docked at Quebrada de las Palmas, a river in Naguabo.[167] From there, Cofresí, Hernández Morales, Juan Francisco "Ceniza" Pizarro and De los Reyes crossed the mangroves and vegetation to the Quebrada barrio in Fajardo. [167][168] Joined by a fugitive, Juan Pedro Espinoza, the group robbed the house of Juan Becerril[nb 5][75] and hid in a house in the nearby Río Abajo barrio.[167] Two days later Cofresí again led his flotilla out to sea[169] and targeted San Vicente, a Spanish sloop making its way back from Saint Thomas.[169] Cofresí attacked with two sloops, ordering his crew to fire muskets and blunderbusses.[169] Sustaining heavy damage, San Vicente finally escaped because she was near port.[167]

On February 10, 1825, Cofresí plundered the sloop Neptune.[nb 6][171] The merchant ship, with a cargo of fabric and provisions, was attacked while its dry goods were unloaded at dockside in Jobos Bay.[170] Neptune was owned by Salvador Pastorisa, who was supervising the unloading. Cofresí began the charge in a sloop, opening musket fire on the crew,[170] and Pastoriza fled in a rowboat.[170] Despite a bullet wound, Pastoriza identified four of the eight to ten pirates (including Cofresí).[172] An Italian living in Puerto Rico, Pedro Salovi, was reportedly[173] second-in-command during the attack.[174] The pirates pursued and shot those who fled.[172] Cofresí sailed Neptune out of Jobos Port, a harbor in Jobos Bay (near Fajardo), and adopted the sloop as a pirate ship.[173]

Guayama mayor Francisco Brenes doubled his patrol.[172] Salovi was soon arrested, and informed on his shipmates.[174] Hernández Morales led another sloop, intercepting Beagle off Vieques.[174] After a battle, the pirate sloop was captured and Hernández Morales was transported to St. Thomas for trial.[175] After being sentenced to death, he escaped from prison and disappeared for years.[176] According to a St. Thomas resident, on February 12, 1825, the pirates retaliated by setting fire to a town on the island.[177] That week, Neptune captured a Danish schooner belonging to W. Furniss (a company based in Saint Thomas) off the Ponce coast with a load of imported merchandise.[173] After the assault, Cofresí and his crew abandoned the ship at sea. Later seen floating with broken masts, it was presumed lost.[173] Some time later Cofresí and his crew boarded another ship owned by the company near Guayama, again plundering and abandoning her.[173] Like its predecessor, it was seen near Caja de Muertos (Dead Man's Chest) before disappearing.

Evading Beagle, Cofresí returned to Jobos Bay;[178] on February 15, 1825, the pirates arrived in Fajardo.[178] Three days later John Low picked up a six-gun sloop, Anne (commonly known by her Spanish name Ana or La Ana), which he had ordered from boatbuilder Toribio Centeno and registered in St. Thomas.[nb 7][178] Centeno sailed the sloop to Fajardo, where he received permission to dock at Quebrada de Palmas in Naguabo.[178] As its new owner Low accompanied him, remaining aboard while cargo was loaded.[179] That night Cofresí led a group of eight pirates, stealthily boarded the ship[179] and forced the crew to jump overboard;[157] during the capture, Cofresí reportedly picked $20 from Low's pocket.[173] Despite having to "walk the plank", Low's crew survived[157] and reported the assault to the governor of Saint Thomas.[173] Low probably attracted the pirates' attention by docking near one of their hideouts; his work on the Beagle rankled, and they were hungry for revenge after the capture of Hernández Morales.[180] Low met Centeno at his hacienda, where he told the Spaniard about the incident and later filed a formal complaint in Fajardo.[180] Afterwards, he and his crew sailed to Saint Thomas.[180] Although another account suggests that Cofresí bought Anne from Centeno for twice Low's price,[181] legal documents verify that the builder was paid by Low.[173] Days later, Cofresí led his pirates to the Humacao shipyard[182] and they stole a cannon from a gunboat (ordered by Miguel de la Torre to pursue the pirates) which was under construction.[182] The crew armed themselves with weapons found on the ships they boarded.[181]

After the hijacking, Cofresí adopted Anne as his flagship.[179] Although she is popularly believed to have been renamed El Mosquito, all official documents use her formal name.[183][184] Anne was quickly used to intercept a merchant off the coast of Vieques who was completing a voyage from Saint Croix to Puerto Rico.[182] Like others before it, the fate of the captured ship and its crew is unknown.[182] The Spanish countered with an expedition from the port of Patillas.[182] Captain Sebastián Quevedo commanded a small boat, Esperanza, to find the pirates but was unsuccessful after several days at sea.[182] At the same time, de la Torre pressured the regional military commanders to take action against the pirates and undercover agents monitored maritime traffic in most coastal towns.[182] The pirates docked Anne in Jobos Bay before sunset, a pattern reported by the local militia to southern region commander Tomás de Renovales.[185] At this time the pirates sailed Anne towards Peñuelas, where the ship was recognized.[185] Cofresí's last capture was on March 5, 1825, when he commanded the hijacking of a boat owned by Vicente Antoneti in Salinas.[186]

Capture and trial

By the spring of 1825, the flotilla led by Anne was the last substantial pirate threat in the Caribbean.[187] The incursion which finally ended Cofresí's operation began serendipitously. When Low arrived at his home base in Saint Thomas with news of Anne's hijacking, a Puerto Rican ship reported a recent sighting.[188] Sloat requested three international sloops (with Spanish and Danish papers) from the Danish governor, collaborating with Pastoriza and Pierety. All four of Cofresí's victims left port shortly after the authorization on March 4; the task force was made up of Grampus, San José y Las Animas, an unidentified vessel belonging to Pierety and a third sloop staffed by volunteers from a Colombian frigate.[188] After sighting Anne while they negotiated the involvement of the Spanish government in Puerto Rico, the task force decided to split up.[188]

San José y Las Animas found Cofresí the next day, and mounted a surprise attack. The sailors aboard hid while Cofresí, recognizing the ship as a local merchant vessel, gave the order to attack it.[188] When Anne was within range, the crew of San José y las Animas opened fire. Startled, the pirates countered with cannon and musket fire while attempting to outrun the sloop.[189] Unable to shake off San José y las Animas and having lost two members of his crew, Cofresí grounded Anne and fled inland.[190] Although a third pirate fell during the landing, most scattered throughout rural Guayama and adjacent areas.[189] Cofresí, injured, was accompanied by two crew members.[191] Half his crew was captured shortly afterwards, but the captain remained at large until the following day. At midnight a local trooper, Juan Cándido Garay, and two other members of the Puerto Rican militia spotted Cofresí.[192] The trio ambushed the pirate, who was hit by blunderbuss fire while he was fleeing.[192] Despite his injury, Cofresí fought back with a knife until he was subdued by militia machetes.[192]

After their capture, the pirates were held at a prison in Guayama before their transfer to San Juan.[193] Cofresí met with mayor Francisco Brenes, offering him 4,000 pieces of eight (which he claimed to possess) in exchange for his freedom.[194] Although a key component of modern myth, this is the only historical reference to Cofresí's hiding any treasure.[194] Brenes declined the bribe.[195] Cofresí and his crew remained in Castillo San Felipe del Morro in San Juan for the rest of their lives.[56] On March 21, 1825, the pirate's reputed servant (known only as Carlos) was arrested in Guayama.[196]

Military prosecution

Cofresí received a council of war trial, with no possibility of a civil trial.[197] The only right granted the pirates was to choose their lawyers;[198] the arguments the attorneys could make were limited, and their role was a formality.[198] José Madrazo was again the prosecutor.[199] The case was hurried—an oddity, since other cases as serious (or more so) sometimes took months or years. Cofresí was reportedly tried as an insurgent corsair (and listed as such in a subsequent explanatory action in Spain),[197] in accordance with measures enacted by governor Miguel de la Torre the year before.[101] It is thought that the reason for the irregularities was that the Spanish government was under international scrutiny, with several neutral countries filing complaints about pirate and privateer attacks in Puerto Rican waters;[197] there was additional pressure due to the start of David Porter's court-martial in the United States for invading the municipality of Fajardo.[197] The ministry rushed the Cofresí trial, denying him and his crew defense witnesses or testimony (required by trial protocol).[197] The trial was based on the pirates' confessions, with their legitimacy or circumstances not established.[197]

The other pirates on trial were Manuel Aponte Monteverde of Añasco; Vicente del Valle Carbajal of Punta Espada (or Santo Domingo, depending on the report);[200] Vicente Ximénes of Cumaná; Antonio Delgado of Humacao; Victoriano Saldaña of Juncos; Agustín de Soto of San Germán; Carlos Díaz of Trinidad de Barlovento; Carlos Torres of Fajardo; Juan Manuel Fuentes of Havana, and José Rodríguez of Curaçao.[70] Torres stood out as an African and Cofresí's slave.[201] Among the few sentenced for piracy who were not executed, his sentence was to be sold at public auction with his price earmarked for trial costs.[201] Cofresí confessed to capturing a French sloop in Vieques; a Danish schooner; a sailing ship from St. Thomas; a brigantine and a schooner from eastern Hispaniola; a sloop with a load of cattle in Boca del Infierno; a ship from which he stole 800 pieces of eight in Patillas, and an American schooner with a cargo worth 8,000 pieces of eight (abandoned and burned in Punta de Peñones).[70]

Under pressure, he was adamant that he was unaware of the current whereabouts of the vessels or their crews and that he had never killed anyone; his testimony was corroborated by the other pirates.[70] However, according to a letter sent to Hezekiah Niles' Weekly Register Cofresí admitted off the record that he had killed nearly 400 people (but no Puerto Ricans).[202] The pirate also confessed that he burned the cargo of an American vessel to throw off the authorities.[132] The defendants' social status and association with criminal (or outlaw) elements dictated the course of events. Captain José Madrazo served as judge and prosecutor of the one-day trial.[197] Governor Miguel de la Torre may have influenced the process, negotiating with Madrazo beforehand. On July 14, 1825, U.S. Congressman Samuel Smith accused Secretary of State Henry Clay of pressuring the Spanish governor to execute the pirates.[197]

Death and legacy

On the morning of March 29, 1825, a firing squad was assembled to carry out the sentence handed down to the pirates.[203] The public execution, which had a large number of spectators,[204] was supervised by the Regimiento de Infantería de Granada between eight and nine a.m. Catholic priests were present to hear confessions and offer comfort.[204] As the pirates prayed, they were shot before the silent crowd.[204] Although San Felipe del Morro is the accepted execution site, Alejandro Tapia y Rivera (whose father was a member of the Regimiento de Granada) places their execution near Convento Dominico in the Baluarte de Santo Domingo (part of present-day Old San Juan).[204] According to historian Enrique Ramírez Brau, in a final act of defiance Cofresí refused to have his eyes covered after he was tied to a chair and he was blindfolded by soldiers.[158] Richard Wheeler said that the pirate said that after killing three or four hundred people, it would be strange if he was not accustomed to death.[205] Cofresí supposedly said he had "killed four hundred persons with his own hands, but never to his knowledge had he killed a native of Puerto Rico."[206] Cofresí's last words were reportedly, "I have killed hundreds with my own hands, and I know how to die. Fire!"[92]

According to several of the pirates' death certificates, they were buried on the shore next to the Santa María Magdalena de Pazzis Cemetery.[208] Hernández Morales and several of his associates received the same treatment.[209] Cofresí and his men were buried behind the cemetery, on what is now a lush green hill overlooking the cemetery wall. Contrary to local lore, they were not buried in Old San Juan Cemetery (Cementerio Antiguo de San Juan); their execution as criminals made them ineligible for burial in the Catholic cemetery.[56] A letter from Sloat to United States Secretary of the Navy Samuel L. Southard implied that at least some of the pirates were intended to be "beheaded and quartered, and their parts sent to all the small ports around the island to be exhibited".[92] Spanish authorities continued to arrest Cofresí associates until 1839.

At this time defendants were required to pay trial expenses, and Cofresí's family was charged 643 pieces of eight, two reales and 12 maravedí.[197] Contemporary documents suggest that Juana Creitoff, with little or no support from Cofresí's brothers and sisters, was left with the debt. His brothers distanced themselves from the trial and their brother's legacy, and Juan Francisco left Cabo Rojo for Humacao. Juan Ignacio also evidently disassociated himself from Creitoff and her daughter,[197] and one of Juan Ignacio's granddaughters ignored Bernardina and her descendants.[57] Due to Cofresí's squandering of his treasure, his only asset the Spanish government could seize was Carlos. Appraised at 200 pesos, he was sold to Juan Saint Just for 133 pesos.[210] After the auction costs were paid, only 108 pesos and 2 reales were left; the remainder was paid by Félix and Miguel Mattei[197] after they made a deal with the authorities giving them the cargo of the San José y las Animas in return for future accountability.[210] Juana Creitoff died a year later.[56]

Bernardina later married a Venezuelan immigrant, Estanislao Asencio Velázquez, continuing Cofresí's blood lineage in Cabo Rojo to this day.[211] She had seven children: José Lucas, María Esterlina, Antonio Salvador, Antonio Luciano, Pablo, María Encarnación and Juan Bernardino.[211] One of Cofresí's most notable descendants was Ana González, better known by her married name Ana G. Méndez.[212] Cofresí's great-granddaughter, Méndez was directly descended from the Cabo Rojo bloodline through her mother Ana González Cofresí.[212] Known for her interest in education, she was the first member of her branch of the Cofresí family to earn a high-school diploma and university degree.[212] A teacher, Méndez founded the Puerto Rico High School of Commerce during the 1940s (when most women did not complete their education).[212] By the turn of the 21st century her initiative had evolved into the Ana G. Méndez University System, the largest group of private universities in Puerto Rico.[212] Other branches of the Cofresí family include Juan Francisco's descendants in Ponce,[213] and Juan Ignacio's lineage persists in the western region.[213] Internationally, the Kupferschein family remains in Trieste.[6] Another family member was Severo Colberg Ramírez, speaker of the House of Representatives of Puerto Rico during the 1980s.[214] Colberg made efforts to popularize Cofresí, particularly the heroic legends which followed his death.[214] He was related to the pirate through his sister Juana, who married Germán Colberg.[215]

After Cofresí's death, items associated with him have been preserved or placed on display. His birth certificate is at San Miguel Arcángel Church with those of other notable figures, including Ramón Emeterio Betances and Salvador Brau.[216] Earrings said to have been worn by Cofresí were owned by Ynocencia Ramírez de Arellano, a maternal cousin.[217] Her great-great-grandson, collector Teodoro Vidal, gave them to the National Museum of American History in 1997 and the institution displayed them in a section devoted to Spanish colonial history. Locally, documents are preserved in the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture's General Archive of Puerto Rico, the Ateneo Puertorriqueño, the University of Puerto Rico's General Library and Historic Investigation Department and the Catholic Church's Parochial Archives. Outside Puerto Rico, records can be found at the National Archives Building and the General Archive of the Indies.[218] However, official documents relating to Cofresí's trial and execution have been lost.[219]

Modern view

Few aspects of Cofresí's life and relationships have avoided the romanticism surrounding pirates in popular culture.[220] During his life, attempts by Spanish authorities to portray him as a menacing figure by emphasizing his role as "pirate lord" and nicknaming him the "terror of the seas" planted him in the collective consciousness.[221] This, combined with his boldness, transformed Cofresí into a swashbuckler differing from late-19th-century fictional accounts of pirates.[222] The legends are inconsistent in their depiction of historical facts, often contradicting each other.[223] Cofresí's race, economic background, personality and loyalties are among variable aspects of these stories.[224][225] However, the widespread use of these myths in the media has resulted in their general acceptance as fact.[226]

The myths and legends surrounding Cofresí fall into two categories: those portraying him as a generous thief or anti-hero and those describing him as overwhelmingly evil.[227] A subcategory represents him as an adventurer, world traveler or womanizer.[228] Reports by historians such as Tió of the pirate sharing his loot with the needy have evolved into a detailed mythology. These apologetics attempt to justify his piracy, blaming it on poverty, revenge or a desire to restore his family's honor,[229] and portray Cofresí as a class hero defying official inequality and corruption.[230] He is said to have been a protector and benefactor of children, women and the elderly,[227] with some accounts describing him as a rebel hero and supporter of independence from imperial power.[231]

Legends describing Cofresí as malevolent generally link him to supernatural elements acquired through witchcraft, mysticism or a deal with the Devil.[232] This horror fiction emphasizes his ruthlessness while alive or his unwillingness to remain dead.[233] Cofresí's ghost has a fiery aura or extraordinary powers of manifestation, defending the locations of his hidden treasure or roaming aimlessly.[234] Cofresí has been vilified by merchants.[235] Legends portraying him as benign figure are more prevalent near Cabo Rojo; in other areas of Puerto Rico, they focus on his treasure and depict him as a cutthroat.[236] Most of the hidden-treasure stories have a moral counseling against greed; those trying to find the plunder are killed, dragged to Davy Jones' Locker or attacked by the ghost of Cofresí or a member of his crew.[237] Rumors about the locations of hidden treasure flourish, with dozens of coves, beaches and buildings linked to pirates in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. [238]

The 20th century revived interest in Cofresí's piracy as a tourist attraction, with municipalities in Puerto Rico highlighting their historical connection to the pirates.[239] By the second half of the century, beaches and sports teams (especially in his native Cabo Rojo, which features a monument in his honor) were named for him; in the Dominican Republic, a resort town was named after the pirate.[240] Cofresí's name has been commercialized, with a number of products and businesses adopting it and its associated legends.[241] Puerto Rico's first flag carrier seaplane was named for him.[242][243] Several attempts have been made to portray Cofresí's life on film, based on legend.[244]

Coplas, songs and plays have been adapted from the oral tradition, and formal studies of the historical Cofresí and the legends surrounding him have appeared in book form.[218] Historians Cardona Bonet, Acosta, Salvador Brau, Ramón Ibern Fleytas, Antonio S. Pedreira, Bienvenido Camacho, Isabel Cuchí Coll, Fernando Géigel Sabat, Ramírez Brau and Cayetano Coll y Toste have published the results of their research.[218] Others inspired by the pirate include poets Cesáreo Rosa Nieves and the brothers Luis and Gustavo Palés Matos.[218] Educators Juan Bernardo Huyke and Robert Fernández Valledor have also published on Cofresí.[218] In mainstream media Cofresí has recently been discussed in the newspapers El Mundo, El Imparcial, El Nuevo Día, Primera Hora, El Periódico de Catalunya, Die Tageszeitung, Tribuna do Norte and The New York Times,[218][245][246][247] and the magazines Puerto Rico Ilustrado, Fiat Lux and Proceedings have published articles on the pirate.[218]

See also

- List of Puerto Ricans

- List of pirates

- Miguel Enríquez (privateer)

- Folklore of Puerto Rico

- Folk hero

References

Notes

- ↑ In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Cofresí and the second or maternal family name is Ramírez de Arellano.

- ↑ During his lifetime his name was frequently confused, giving rise to variants including Roverto Cofresin, Roverto Cufresín, Ruberto Cofresi, Rovelto Cofusci, Cofresy, Cofrecín, Cofreci, Coupherseing, Couppersing, Koffresi, Confercin, Confersin, Cofresin, Cofrecis, Cofreín, Cufresini, and Corfucinas.[1]

- ↑ This ship is also known as Esscipión or Escipión.[64]

- ↑ Despite having an etymology based on pilot boat, the term "pailebot" is used in Spanish to describe a small schooner.

- ↑ The Spanish referred to the vessel as the Princesa Buena Sofia.

- ↑ This ship was also listed as Los Dos Amigos

- ↑ Espinoza had previous ties with Pedro Salovi, another of Cofresí's associates

- ↑ This ship was also known as Esperanza.[170]

- ↑ Anne is frequently referred to as a schooner.

Citations

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 202

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 25

- 1 2 3 Acosta 1991, pp. 14

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 16

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 212

- 1 2 3 4 Acosta 1991, pp. 27

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 13

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 28

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 29

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 30

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 31

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 26

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 32

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 17

- 1 2 3 Acosta 1991, pp. 33

- 1 2 3 4 Acosta 1987, pp. 94

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 36

- ↑ Acosta 1987, pp. 89

- ↑ Fernández Valledor 2006, pp. 92

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 41

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 43

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 34

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 35

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 26

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 27

- ↑ Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 42

- ↑ Acosta 1987, pp. 91

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 37

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 47

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 44

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 45

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 56

- 1 2 3 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 49

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 28

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 57

- ↑ Fernández Valledor 2006, pp. 80

- 1 2 3 Fernández Valledor 2006, pp. 81

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 71

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 58

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 50

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 30

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 31

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 34

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 32

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 33

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 48

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 36

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 47

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 39

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 40

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 45

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 41

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 44

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 17

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 49

- 1 2 3 4 5 Puerto Rican Folkloric Dance, Retrieved April 2, 2008

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 82

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 258

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 50

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 51

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 52

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 29

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 55

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 78

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 59

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 54

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 57

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 61

- 1 2 3 Acosta 1991, pp. 62

- 1 2 3 4 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 66

- 1 2 3 4 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 125

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 73

- 1 2 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 50

- ↑ Fernández Valledor 2006, pp. 125

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 156

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 295

- 1 2 Gladys Nieves Ramírez (2007-07-28). "Vive el debate de si el corsario era delincuente o benefactor". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- ↑ Cabo Rojo: datos históricos, económicos, culturales y turísticos. Municipio Autónomo de Cabo Rojo. n.d. p. 15.

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 64

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 65

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 66

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 67

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 69

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 70

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 74

- ↑ Acosta 1991, pp. 60

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 62

- ↑ Antonio Heredia (2013-06-24). "Viceministro de Educación dictará conferencia en PP; pondrá en circulación libro" (in Spanish). Puerto Plata Digital. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Clammer, Grosberg & Porup 2008, pp. 150

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eugenio Astol (1936-05-09). El contendor de los gobernadores (in Spanish). Puerto Rico Ilustrado.

- 1 2 3 Freeman Hunt (1846). "Naval and Mercantile Biography". Hunt's Merchants' Magazine. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 72

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 75

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 279

- ↑ Fernández Valledor 2006, pp. 91

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 81

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 85

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 79

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 155

- 1 2 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 56

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 58

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 304

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 80

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 115

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 76

- 1 2 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 127

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 82

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 83

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 84

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 86

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 87

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 88

- 1 2 3 Acosta 1991, pp. 65

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 90

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 91

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 92

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 93

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 94

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ojeda Reyes 2001, pp. 7

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 95

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 100

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 101

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 104

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 103

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 219

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 220

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 105

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 102

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 106

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 107

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 108

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 109

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 110

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 111

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 113

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 230

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 114

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 116

- 1 2 Acosta 1991, pp. 66

- ↑ Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 57

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 121

- 1 2 3 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 122

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 123

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 124

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 125

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 245

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 128

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 129

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 133

- ↑ Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 131

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 130

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 135

- 1 2 3 4 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 140

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 141

- 1 2 Cardona Bonet 1991, pp. 138

- 1 2 3 4 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 105

- 1 2 Fernández Valledor 1978, pp. 68