| Castello Normanno-Svevo | |

|---|---|

Norman-Swebian castle | |

| | |

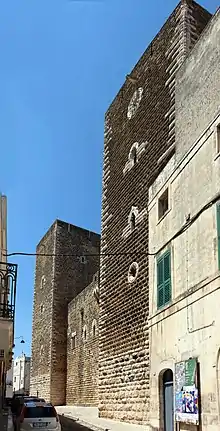

Torre De' Rossi | |

Castello Normanno-Svevo | |

| Coordinates | 40°48′01″N 16°55′22″E / 40.800278°N 16.922778°E |

| Height | 26.4 m |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Website | https://musei.puglia.beniculturali.it/musei/museo-archeologico-nazionale-castello-di-gioia-del-colle/ |

| Site history | |

| Built | 9th–11th century |

| Built by | Richard of Hauteville |

| Materials | Limestone, red carparo |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | |

The Castello Normanno-Svevo (in English: Norman-Swebian castle) is a Normans' castle located in the historic center of Gioia del Colle. Since December 2014, the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities has managed the entire castle through the Polo Museale della Puglia, which, in December 2019, became the Direzione Regionale Musei.

History

Byzantine origins

The ancient centre of the Castle, corresponding to the North wing, is from the period of the Byzantine Empire, dating back to the 9th century. It was composed of a rectangular fortified enclosure in limestone. There was a small courtyard, adjacent to the southern wall. It opened outwards in what is now known as the Martyrs' square of 1799. The main function of the Castle was to offer shelter to the population, in case of enemy raids.[1]

Norman period

Between the 9th and 10th centuries, the castle was expanded by Richard of Hauteville, who belonged to the Norman dynasty of Hauteville, was the Duke of Apulia, and was the first lord of the territory of the current Gioia del Colle. The oldest document where the Castle is mentioned dates back to 1108, so the expansion could have been before the Norman enlargement. Richard of Hauteville transformed the Byzantine fortress into a feudal stronghold. He expanded the yard to the south and enclosed it with a solid wall. He built a fortified tower in the southwest corner, later named "Torre De' Rossi". The King of Sicily, Roger II of Sicily, of Norman ancestry, changed the fortification partially and added two towers in the northeast and northwest corners, which no longer exist.

The castle and the surrounding built-up area were destroyed by William I of Sicily when he regained power over the land of Bari.

Swebian period

The current placement is attributed to Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, who refunded the Castrum and added a tower in the southeast corner (also named "Torre Imperatrice") around 1230,[1] when he came back from the Fourth Crusade in the Holy Land. He erected curtain walls in the yard to obtain closed areas, service rooms on the ground floor (kitchen, storages, stalls, stables), and residential areas on the first floor.

The building had a roughly quadrangular structure, with an inner courtyard, which was typical of the Frederican's Castles.[1] The castle, wanted by the emperor, was part of the nets of residences and fortifications[1] which were scattered throughout the territory of Southern Italy. From Capitanata to Sicily, these were destined to improve the military control of the prolific areas of the Kingdom. Throughout the Swebian period, the Castle of Gioia del Colle was indeed the headquarters of a military garrison. Only a few areas were free and property of the king. From some narrations and testimonies, it looks like the puer apuliae loved living in the Castle of Gioia for his hunts in the Silvia Regia's woods.

Angevin and Aragonese periods

With the defeat of Manfred, King of Sicily in the Battle of Benevento in 1266, the Swebian hegemony over southern Italy ended and the Castle of Gioia del Colle declined in influence. After the Hohenstaufen, it went under the supremacy of the House of Anjou and of the Crown of Aragon. Manfred – who was born in Gioia del Colle, according to legend – lost the property at his death to the princes of Taranto until the 15th century. Then, it passed to the House of Acquaviva from Conversano until the 17th century, and to the princes of Acquaviva until the beginning of the 19th century.[2]

During these centuries, the castle was transformed from military construction to a residential dwelling and adapted to the new residential need. It had lost all of its military and civil relevance, maintaining its structure.[1] From the 15th century, the Castle began to lose its importance and started a long phase of degradation and disfigurements. However, it kept the original structure, differently from other Apulia's Castles, which underwent various military adaptations. That is why the Castle of Gioia del Colle represents one of the most accurate testimonies of the Norman-Swebian period.

Contemporary age

The castle became the property of Donna Maria Emanuela Caracciolo from 1806 until 1868. In 1884, it was bought by the canonical Daniele Eramo. At the beginning of the 20th century, it passed to the Marquis of Noci, Orazio De Luca Resta, who drew attention to the monument, promoting its restoration, and later suggested its donation to the Municipality of Gioia del Colle. The first restoration works made from 1907 to 1909 by the architect Angelo Pantaleo, dated back to this period, which aimed to recover the original appearance, however carrying out arbitrary reconstructions based on a stereotyped image of the Middle Ages. Among these, there are some single and double lancet windows and the three lancet windows in the internal curtain wall on the south side, as well as the throne and the stone furnishings of the homonymous room. In his reconstructions, however, the architect used reused material, even of considerable value, scrupulously recovered in the demolition of structures, dating back to periods of decay.[1]

In 1955 the castle, which was very run down due to being kept in a state of neglect by the heirs of the Marquis De Luca Resta, was purchased by the Ministry of Public Education (Italy) and included among the national monuments.[1]

Between 1969 and 1974 the castle was restored again, after some collapses following the intervention of 1907, this time by the engineer Raffaele De Vita. He recovered the functionality of the rooms on the ground floor, making it finally open as a monument but also suitable for hosting cultural activities.[3]

Since 1977, the Castle has been the seat of the National Archaeological Museum of Gioia del Colle. Furthermore, for a short period, the Castle hosted the Don Vincenzo Angelillo Municipal Library.

Description

The castle is made of a courtyard and around it some rooms, located on two floors. In two angles in the south side, there are two fortified towers (called "De' Rossi" and "dell'Imperatrice", 28 m and 24 m high), of the four that were originally there. Some references to these towers are in the paper written by Honofrio Tangho in 1640 and that of Gennaro Pinto in 1653.

The exterior is influenced by the stylistic contribution of the different owners with the Frederick II intervention most influential. His work is eclectically rich in different contributions, typical of his tendency to flank very different styles, with particular regard to Islamic architecture. It is evident in the variety of artistic motifs inside the courtyard and rooms, inspired by Arabic models filtered through crusaders. Added to this is the showy Bossage apparatus that gives a note of monumentality to the severe and austere Norman construction. This architectural process, of purely decorative value, is highlighted in the white limestone frames along the edges of the towers and in the original external openings on the facade of the curtains and towers.

The construction material is mainly limestone and red Carparo. The external walling is composed of three different types of masonry structure, representing three different times of realization: small limestone ashlars, on the north and northeast Enceinte, rectangular ashlars with hollowed channels on the Tower of the Empress and rectangular Bossage, worn by time, on the rest of the building. In particular, the red Carparo was used to make the Enceinte and the high part of the towers, up to 4.50 m high on the latter. Very light limestone ashlars were used on corners of the towers and the framing of portals, windows and some Embrasure.

Numerous mullioned windows, a trifora (dating back to the restoration of the Pantaleo of 1907) and Embrasure open messily on the Enceintes and on the towers, confirming the different construction phases.[2] The Enceinte are around 12 m high, and they are divided into two floors. The inferior one shows numerous narrow Embrasures, the superior ones many windows of different shapes.

Entrances

There are various entrances: the main entrance is formed by a large portal located on the west side, a second one is little more than a gate on the south side. Both are surmounted by a wreath of ashlar radials. Two Machicolation tailpipes loom above the entrances.

A third entrance was unearthed through the north curtain.

Courtyard

From the main entrance, with its arch, there is access to the trapezoidal courtyard, where the stairs for the upper floor are found. The staircase has some Bas-Relief, which represents animals and hunting scenes.[1]

In the middle of the courtyard, there is a cistern shaft for rainwater collection. The inner Enceintes on the north and west side of the courtyard have been rebuilt.[1]

Courtyard

Courtyard A portal in the courtyard

A portal in the courtyard The staircase in the courtyard

The staircase in the courtyard

Rooms of the archaeological museum

From the courtyard, there is access to the rooms on the ground floor intended in the past to house stables, servants and men of arms, as well as the storage of wheat and provisions.

These last rooms present the exhibitions of the National Archaeological Museum of Gioia del Colle, which collects the findings from archaeological excavation carried out in the areas of Monte Sannace and Santo Mola.

Bakery room and dungeon

On the southern side of the courtyard, there is access to the bakery room, from which there is access down to a small underground, used in ancient times as a dungeon. On one of its walls are carved two round shapes, which according to legend represent the breasts of Bianca Lancia, lover of Frederick II of Swabia. According to the same legend, the Empress, who had had an affair with Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, gave birth to Manfred, King of Sicily in the prison of the Castle.

This environment is located at the base of the Empress Tower.

An arch at the end of the throne room served to divide the room into two sectors: one for the Emperor and the other for the subjects and dignitaries who were received in the audience.[1]

The original wooden roof, rebuilt by Pantaleo, collapsed in the 1930s and during the last restoration was replaced with a metal structure, while the floor was covered with wooden elements.

In the room, there is a fireplace and several stone seats, also dating back to the restoration of the Pantaleo.

The throne

The throne The frieze on the back of the throne

The frieze on the back of the throne the fireplace inside the throne room

the fireplace inside the throne room

Fireplace room

From the throne room, there is an entrance to the fireplace room, so-called for the presence of an elegant Renaissance fireplace. The hall, illuminated by a beautiful three-light window, rebuilt by Pantaleo in place of a large original window, was probably used as the dining room of the court. A door, surmounted by a heraldic coat of arms, leads to the Sala del Gineceo, probably for the use of the queen and the courtesans, who spent most of the day there; a second door, instead, leads to the Torre De' Rossi.

Tower De'Rossi

The tower is the keep built in Norman times and then incorporated into the Frederick plant, the name coming from a noble Tuscan family.

A door on the west side opens to interior stairs leading to the upper floors of the tower and then to the terrace.

The vault that covers the room is formed by twelve high hanging arches, joined by a thin square frame with phytomorphic motifs. At the four corners, in the arches' rooms, are four decorative elements in the shell. It was probably built in the 16th century.

Tower of the Empress

From the hall of Gineceo, a staircase leads to what was probably the bedroom of the Castle’s regents. Inside it, there is the so-called Tower of the Empress, located in the southeast corner of the castle. The tower dates back to the Swabian period and was built making extensive use of the very light local limestone. The tower's name refers to Bianca Lancia. She was Fredrick's lover and Manfred's mother, according to a legend in the dungeons' castle, where the Empress was imprisoned on charges of betrayal. The rooms of the castle were reserved for the family. The toilets obtained in a closet on the north side of the room, with an outlet to the outside, were intended for them. The tower was divided into three floors, of which only the corbels remain. On these corbels, the beams of the wooden floors collapsed but were not rebuilt. The upper floors were reached with wooden ladders.

From the top floor, the external platform was reached via a spiral stone staircase, resting on a slab protruding from the wall.

Legend of Federich II and Bianca Lancia

Bianca Lancia, from the family of the Counts of Loreto, managed to win Frederick's heart. The two met in 1225, during his marriage with Isabella II of Jerusalem. Not being able to get married, the two maintained a clandestine relationship from which their children Anna, Manfred and also even Violante were born.[4]

According to a legend that has been handed down by Father and taken up by the historian Pantaleo, during her pregnancy with Manfred, Frederick kept Bianca locked up in a tower of the castle of Gioia del Colle out of jealousy. The princess couldn’t endure the humiliation. Overcome by pain, she cut her breasts and sent them to the Emperor on a tray with the baby. After that, the chronicler concludes, "he passed to another life". Since that day, every night, in the tower of the Castle, now known as the Empress Tower, a faint, heartbreaking lament is heard: the lament of an offended woman who endlessly protests her innocence.[4]

If this is a legend, the story is a little more controversial but no less touching. According to some, in 1246 Frederick – meanwhile the widower of his third wife Isabella – moved from Foggia to the Castle of Gioia del Colle, where he found his lover suffering. The woman then asked him to legitimize the three children born of their love. They joined in a regular marriage, allowing Bianca to be an empress for a few days.[4]

The castle as a cinematographic location

In 1986, Pier Paolo Pasolini chose the castle to film some scenes for the movie The Cospel According to St. Matthew. Both the palace scene of Herod Antipas and the dance of Salome took place in the throne room. Herod's salute to the Magi kings was done at the foot of the monumental staircase in the courtyard.[5]

In the summer of 2014, the castle was chosen as a location for the filming of two other movies of the historical-literary genre. Francesco, which speaks about the saint of Assisi, directed by Liliana Cavani,[6] filmed some scenes there. The famous scene of the encounter between S. Francis and the Sultan was set in the throne room. Some short scenes about Francis' illness were set in the "Torre Imperatrice". Additionally, some scenes from the movie Tale of Tales (2015 film), directed by Matteo Garrone, were inspired by the Pentamerone by Giambattista Basile.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Francesco Giannini (2007-03-23). "Il Castello Normanno – Svevo". Gioia del Colle Info. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- 1 2 Cosimo Enrico Marseglia (2018-09-30). "Fortezze Di Puglia: Il Castello Normanno-Svevo Di Gioia Del Colle". Corriere Salentino. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ↑ "Castello Normanno-Svevo". Istituto per le Tecnologie della Costruzione Gioia del Colle. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- 1 2 3 stupromundi.it Archived 30 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Franco Petrelli (2020-06-25). "Gioia del Colle, Gesù di Pasolini nel ricordo dei figuranti del film". www.lagazzettadelmezzogiorno.it. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ↑ "Inizio riprese "La prima luce" di Vincezo Marra e "Francesco" di Liliana Cavani". Apulia Film Commission. 2014-06-20. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ↑ "Il racconto dei racconti girato nel Castello di Gioia vince sette David di Donatello". GioiaNews. 2016-04-19. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

Bibliography

- Benedettelli, M. (1999). Gelao, Clara; Jacobitti, Gian Marco (eds.). Gioia del Colle. Il castello: i restauri. Castelli e Cattedrali di Puglia: a cent’anni dall’esposizione nazionale di Torino. Bari: Adda Editore. pp. 553–555.

- Bonaventura Da Lama (1723). Cronica de' minori osservanti riformati della provincia di S. Nicolò. Lecce.