| Cedar train wreck | |

|---|---|

Norfolk and Western 611, the locomotive involved in the wreck | |

| |

| Details | |

| Date | January 23, 1956 12:51 a.m. |

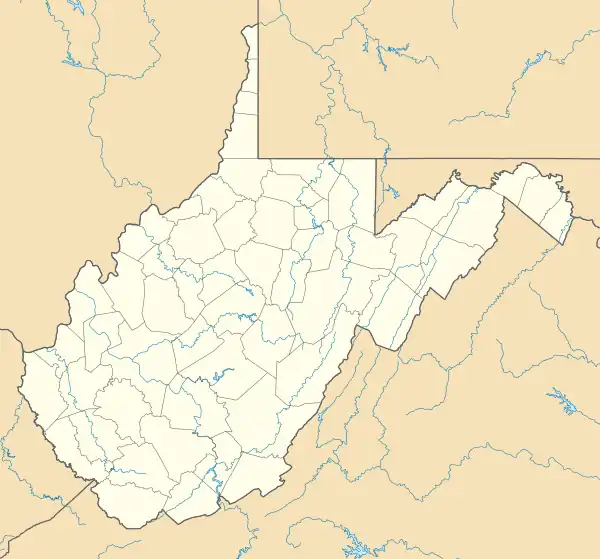

| Location | Cedar, Mingo County, West Virginia |

| Coordinates | 37°33′11″N 82°6′10″W / 37.55306°N 82.10278°W |

| Country | |

| Line | Pocahontas Division |

| Operator | Norfolk and Western Railway |

| Service | Passenger train |

| Incident type | Derailment |

| Cause | Excessive speed on curve |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | 91 |

| Crew | 10 |

| Deaths | 1 |

| Injured | 60 |

| References:[1] | |

The Cedar train wreck occurred on the night of January 23, 1956, when the Norfolk and Western (N&W) Pocahontas passenger train derailed at more than 50 mph (80 km/h) along the Tug River near Cedar, West Virginia. The accident killed the engineer and injured 51 passengers and nine crew members. It was the last major wreck of a steam-powered revenue passenger train in the United States.

The train had been pulled by N&W No. 611, a class J 4-8-4 steam locomotive, which received extensive repairs after the accident and was returned to revenue service. These repairs left No. 611 in excellent condition when it was retired just three years later, which helped lead to its restoration to operating condition for excursion service in 1982 by N&W's successor Norfolk Southern (NS) and again in 2015 by the Virginia Museum of Transportation (VMT).

Accident

On a cold winter night of January 22, 1956, class J 4-8-4 No. 611 left Bluefield, West Virginia, at 10:34 pm, with the westbound Pocahontas train from Norfolk, Virginia, to Cincinnati, Ohio, running 14 minutes late.[2][3] It pulled 11 cars: an express baggage car, No. 123;[4]: 2 a railway post office (RPO) car, No. 94;[4]: 1 a P3 class coach, No. 539;[4]: 8 three Pm class coaches, Nos. 1727, 1729, and 1734;[4]: 27–28 a Pm class tavern-lounge car, No. 1722;[4]: 27 a De class dining car, No. 1022;[4]: 15 and three Pullman sleeping cars: Sicoto County, Mingo County, and Ohio State University.[3][5] The train stopped at Welch, West Virginia, to pick up mail, producing more delays.[3] The speed limit through the N&W's Pocahontas Division in West Virginia was 20–30 mph (32–48 km/h), but engineer Walter B. Willard was desperately trying to make up the lost time and had the train running more than 50 mph (80 km/h).[3]

At 12:51 a.m. on January 23, No. 611 was running near Cedar, West Virginia.[2][3] It flew off the curved tracks and slid down the embankment of the Tug River, where it toppled onto its left side along with its tender and the first six cars.[2][3] The tender turned upside down.[6][7] The first car, baggage car No. 123 was disconnected from the tender, slid down onto its left side, and buckled.[6][7] The second car, RPO No. 94 ended up almost parallel on the track with its front end near the rear end of the baggage car.[6][7] The third car, P3 coach No. 539 toppled onto its left side, near the end of the RPO with its rear end at the edge of the river.[6][7] The fourth car, Pm coach No. 1727 was upright but at a right angle next to the track with the front end near the rear of the third car and the edge of the river.[6][7] The fifth and sixth cars, Pm coach Nos. 1729 and 1734 were scattered with minor damage, but remained in line with the track.[6][7] The last five cars remained on the rails, undamaged.[7] This was the last major steam-powered revenue passenger train wreck in America.[5][lower-alpha 1]

Willard was the only person killed in the wreck.[7] Fireman Ernest W. Hoback survived with abrasions, bruises, and lacerations.[7] The eight other crew members also sustained injuries: conductor Edward N. Camden, porter J.O. Marrs, express clerk James McGlothlin, three postal clerks, and two brakemen.[1][2] Also injured were 51 passengers.[1]

Aftermath

Rescue and recovery operations

Some 15 ambulances arrived on the scene after 1 a.m.[5][7] Three maintenance of way (MOW) wreck trains arrived from Williamson, Iaeger, and Bluefield at 3:15, 5:00, and 11:00 a.m., respectively.[7] 25 injured people were taken to the nearby Williamson Memorial Hospital in Williamson.[5] Because the accident damaged the rails in Cedar, the N&W trains took a detour over the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) tracks between Gilbert and Kenova, West Virginia.[5][7]

40 uninjured passengers took refuge in the three sleeping cars along with the dining car and tavern-lounge car, which were all towed back to Iaeger, where the sleeping cars were picked up by the westbound Cavalier train, while the dining car and tavern-lounge car were picked up by the eastbound Pocahontas train.[7] The westbound track at Cedar was minorly damaged with a kinked rail and the track was shifted over from the force of the wreck.[7] After replacing the kinked rail, a bulldozer shoved the track back into place, and the westbound track reopened on January 24 at 11:25 a.m.[7][9] The eastbound track, where the train derailed, was severely damaged and got pushed down the embankment for 340 ft (103.63 m), from about 55 ft (16.76 m) east of the point of the accident.[9] The MOW crew quickly repaired the eastbound track and it reopened that same day at 1:30 p.m.[9] About 10:10 p.m., they began to rerail the six damaged cars and towed all of them to Williamson for inspection.[9]

No. 611 was the most difficult rolling stock to get rerailed.[9] The MOW crew had to disconnect the locomotive from its tender and rerail it one set of wheels at a time.[9] On the afternoon of January 26, No. 611 was finally back on the rails and towed to Williamson for inspection.[5][9] The locomotive's skirting panels, running boards, valve gear parts, and other appliance parts were torn off from its left side.[2][3]

The estimated damage cost to the six cars was $6,000 to the express baggage car, $7,500 to the RPO car, $12,000 to coach No. 539, and $9,000 to coach No. 1727.[9] The damages to coaches Nos. 1729 and 1734 were estimated at $2,000 and $1,000 respectively.[9] The damaged tracks were estimated at $5,240.[9] Other expenses such as the wages of the wreck car forces, section men, and train crews totaled another $23,866.21.[9] The damage to No. 611 and its tender was estimated at $75,000.[9] The total damage cost of the accident was around $141,606.21.[9]

Rolling stock disposition

The No. 611 locomotive and the six damaged cars were towed back to the Roanoke Shops in Roanoke, Virginia, where they were all repaired and put back into service in less than a month.[9][10] However, the locomotive's sand dome and tender retained their dents.[10][11] In 1959, No. 611 was retired from revenue service and donated to the Roanoke City Council, who put it on display at the Virginia Museum of Transportation (VMT), thanks to the efforts of Washington, D.C. lawyer W. Graham Claytor Jr., who convinced the N&W that No. 611 was in excellent condition after its accident.[11][12]

In 1981–1982, N&W's successor, Norfolk Southern (NS) restored the locomotive to operating condition for use in pulling excursion trains on their steam program until it returned to the VMT in 1995.[13][14] In 2013–2015, VMT restored No. 611 to operation again with $3.5 million donated from nearly 3,000 donors all over the United States and 18 foreign countries.[13][15] The dents on the locomotive's tender were also removed during its restoration.[16] The VMT now operated No. 611 as a traveling exhibit.[13]

The first car, express baggage car No. 123, was sold for scrap in 1968 at Kaplan's Scrapyard in Elmira, New York.[4]: 2 [17] The second car, RPO No. 94, was scrapped in Roanoke around 1968.[4]: 1 The third car, P3 class coach No. 539, was retired from N&W passenger service in 1971 and used in commuter rail service in Chicago, Illinois.[18] In 1982, it was acquired by NS for use in their steam program until it was donated to the Watauga Valley Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society (NRHS) ten years later, where it was now use for lease in public and private excursions by Amtrak and some various heritage railroads and railroad museums.[18][19] The fourth and fifth cars, Pm class Nos. 1727 and 1729, were both sold to the Ontario Northland Railway in 1971.[4]: 27 The sixth car, Pm class No. 1734, was renumbered to 1008 in 1970.[4]: 28 One of the undamaged cars, the Ohio State University was preserved and currently owned by the Florida-Georgia Railway Heritage Museum, which operated it in excursion service on their Georgia Coastal Railway in Kingsland, Georgia.[20]

Investigations

The Interstate Commerce Commission accident report No. 3676 found that the accident was caused by an excessive speed on curve.[1][21] Hoback said Willard had applied the brakes and closed the locomotive's throttle to slow the train down before it hits the curve.[2][3] One of the passengers, Williamson yard engineer W.O. Hylton said that No. 611 traveled at 57.60 mph (93 km/h) from the speed board to the point of the accident.[3][9] One N&W official said that Willard had been a "careful" engineer with 30 years of experience on the Pocahontas Division.[11] The Williamson Daily News newspaper said that Willard suffered a heart attack and was unable to slow the train down.[9][22] The Roanoke Times newspaper reported on February 3 that Willard had been scalded to death by the steam.[11]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 Interstate Commerce Commission Report No. 3676 – January 23, 1956. Interstate Commerce Commission (Report). March 23, 1956. Archived from the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hensley & Miller (2021), p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Miller (2000), p. 97.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Norfolk & Western Steel Passenger Car Roster" (PDF). Norfolk & Western Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hensley & Miller (2021), p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hensley & Miller (2021), p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Miller (2000), pp. 98–99.

- ↑ "Norfolk & Western Steam in the 1950s Volume 1". Pentrex. Archived from the original on October 24, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Miller (2000), p. 100.

- 1 2 Hensley & Miller (2021), p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller (2000), p. 101.

- ↑ Miller (2000), pp. 121–122.

- 1 2 3 "Norfolk & Western J Class #611". Virginia Museum of Transportation. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ↑ Hensley & Miller (2021), p. 81.

- ↑ Vantuono, William C. (April 8, 2014). "Another steam icon, N&W 611, heads for restoration". Railway Age. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corporation. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ↑ Hensley & Miller (2021), p. 102.

- ↑ "Kaplan's Scrap Yard - official website". Kaplan's Scrap Yard. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- 1 2 "Powhatan Arrow Coach". Watauga Valley Railroad Historical Society & Museum. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Passenger Cars/Whistle Truck". Watauga Valley Railroad Historical Society & Museum. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Ohio State University". Georgia Coastal Railway. Florida-Georgia Railway Heritage Museum. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ Hensley & Miller (2021), p. 41.

- ↑ Miller (2000), p. 96.

Bibliography

- Hensley, Timothy B.; Miller, Kenneth L. (2021). Norfolk and Western Six-Eleven – 3 Times A Lady, Revised Edition (2nd ed.). Norfolk & Western Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9899837-2-3.

- Miller, Kenneth L. (2000). Norfolk and Western Class J: The Finest Steam Passenger Locomotive (1st ed.). Roanoke Chapter, National Railway Historical Society, Inc. ISBN 0-615-11664-7.

Further reading

- Dickinson, Jack L.; Dickinson, Kay Stamper (2010). Wheels Aflame, Whistle Wide Open: Train Wrecks of the N&W Railroad (1st ed.). Dickinson Publisher. ISBN 978-0977411634.