Cedric Ernest Howell | |

|---|---|

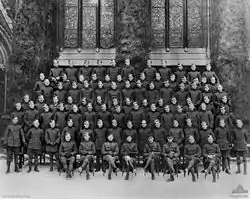

Howell (right) with fellow Australian ace Raymond Brownell in France c. 1917 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Spike" |

| Born | 17 June 1896 Adelaide, South Australia |

| Died | 10 December 1919 (aged 23) St George's Bay, Corfu, Greek Islands |

| Allegiance | Australia (1914–16) United Kingdom (1916–19) |

| Service/ | Australian Army Royal Flying Corps Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1914–1919 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | 46th Battalion (1916) No. 45 Squadron (1917–18) |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Order Military Cross Distinguished Flying Cross Mentioned in Despatches |

Cedric Ernest "Spike" Howell, DSO, MC, DFC (17 June 1896 – 10 December 1919) was an Australian fighter pilot and flying ace of the First World War. Born in Adelaide, South Australia, he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in 1916 for service in the First World War and was posted to the 46th Battalion on the Western Front. In November 1916, he was accepted for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps and was shipped to the United Kingdom for flight training. Graduating as a pilot, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and posted to No. 45 Squadron RFC in France during October 1917; two months later the unit sailed to the Italian theatre.

Howell spent eight months flying operations over Italy, conducting attacks against ground targets and engaging in sorties against aerial forces. While in Italy, he was credited with shooting down a total of nineteen aircraft. In one particular sortie on 12 July 1918, Howell attacked, in conjunction with one other aircraft, a formation of between ten and fifteen German machines; he personally shot down five of these planes and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. He had previously been awarded the Military Cross and Distinguished Flying Cross for his gallantry in operations over the front. He was posted back to the United Kingdom in July 1918. In 1919, Howell was killed while taking part in the England to Australia air race. Piloting a Martinsyde A1 aircraft, he attempted to make an emergency landing on Corfu but the plane fell short, crashing into the sea just off the island's coast. Both Howell and his navigator subsequently drowned.

Early life

Cedric Ernest Howell was born in Adelaide, South Australia,[1][2] on 17 June 1896 to Ernest Howell, an accountant, and his wife Ida Caroline (née Hasch). He was educated at the Melbourne Church of England Grammar School from 1909,[3] and was active in the school's Cadet unit.[4] On completing his secondary studies in 1913, Howell gained employment as a draughtsman. By 1914, he held a commission in the 49th (Prahran) Cadet Battalion, Citizens Military Force, as a second lieutenant.[1][2][3]

First World War

Australian Imperial Force to Royal Flying Corps

On the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Howell attempted to enlist in the newly raised Australian Imperial Force but was initially rejected. The following year, he resigned his commission in the Citizens Military Force and re-applied to join the Australian Imperial Force for active service in the war;[5] he was accepted on 1 January 1916.[6] Due to his age, Howell was ineligible for a commission in the force and was instead granted the rank of private.[7][8] Allotted to the 16th Reinforcements of the 14th Battalion, he embarked aboard HMAT Anchises in Melbourne, Victoria, on 14 March.[6] Arriving in France, he was posted to the newly raised 46th Battalion on 20 May and promoted to corporal four days later. While the unit was engaged in action along the Somme, Howell was temporarily raised to sergeant in July, before taking part in the Battle of Pozières the following month. He relinquished his temporary appointments and reverted to lance corporal in August.[4][9] Considered an expert shot, Howell had been trained as a sniper during his service with the 46th Battalion.[5]

On 11 November 1916, Howell was among a group of 200 Australian applicants selected for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps to undergo flight training.[1][3] Shipped to the United Kingdom, he was posted to No. 1 Royal Flying Officers' Cadet Battalion at Durham for his initial instruction.[3][4][10] On graduating as a pilot, he was formally discharged from the Australian Imperial Force on 16 March 1917 and commissioned as a probationary second lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps the following day.[4][11] Howell was posted to No. 17 Reserve Squadron in April,[3] where his rank was made substantive. Appointed a flight officer on 25 July,[12] he was attached to the Central Flying School for duties.[10] On 12 September, Howell wed Cicely Elizabeth Hallam Kilby in a ceremony at St Stephen's Anglican Church, Bush Hill Park.[3]

Fighter pilot over Italy

In October 1917, Howell was posted to No. 45 Squadron RFC in France, piloting Sopwith Camels.[1][3] Just prior to joining the unit, Howell had suffered a bout of malaria while still in England giving him a "tall, thin and dismal looking" appearance; he was consequently nicknamed "Spike".[5] His service over the Western Front was short-lived, however, as the squadron moved to Italy in late December.[2] While operating over the Italian Front, Howell was engaged in both aerial combat missions and ground-attack sorties, which included "destroy[ing] enemy transport crossing the Alps".[3][13] On 1 April 1918, the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service were combined to form the Royal Air Force, with personnel from the former services transferred to the new branch; Howell thus became a lieutenant in the new service from this date.[3][10]

Throughout the first half of 1918, Howell conducted several raids on ground targets,[1][3] including one on an electrical power plant. From a height of approximately 100 feet (30 m), Howell, with "great skill", scored three direct hits with his bombs on the facility.[13] He was also active in aerial engagements against Central aircraft during this period, achieving flying ace status early in the year.[1] During a particular patrol with two other members of his squadron on 13 May, the trio intercepted a party of twelve enemy planes. In the ensuring battle, Howell "carried out a most dashing attack", being personally credited with the destruction of three of the aircraft and with driving a fourth down out of control, despite suffering "frequent jams in both of his machine guns".[5][13] Cited for his "conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty" in carrying out ground-attack missions, coupled with his destruction of seven Central aircraft, Howell was awarded the Military Cross. The announcement of the decoration was promulgated in a supplement to the London Gazette on 16 September 1918.[13]

Promoted to temporary captain on 1 June 1918,[3][10] Howell led a party of three machines out on patrol eight days later. The trio spotted a formation of six Austrian scout planes and went in to attack; Howell shot down two of the aircraft.[1][5] Later that month, he took off on a similar sortie with two other aircraft. They intercepted a party of nine machines, and during the consequent battle no less than six of the Central planes were destroyed with a seventh shot down as out of control; Howell was credited with two of these. Described as a "fine fighting officer, skilful and determined", Howell was commended for his efforts in destroying five aircraft during June, which resulted in his award of the Distinguished Flying Cross. The notice for the decoration was gazetted on 21 September 1918.[14]

Howell was out on patrol on 15 June 1918 when German and Austrian forces initiated the Battle of the Piave River by striking Allied lines on the opposite bank. After landing back at base at 11:40, he was the first to bring news of the attack. With the aircraft refuelled and loaded with bombs, he—in company with the rest of the squadron—then led his flight on a total of four sorties against the enemy insurgents. No. 45 Squadron succeeded in destroying with its bombs a pontoon bridge, a boat, and a trench filled with soldiers, before inflicting at least a hundred casualties with machine gun fire. Heavy rain washed other bridges away and by 18 June the stranded Austrian forces on the Allied bank of the river were routed by a counterattack.[5]

On 12 July 1918, Howell and Lieutenant Alan Rice-Oxley took to the sky in their Camels.[15] The pair were soon confronted by a formation of between ten and fifteen Central aircraft. As the consequent dogfight raged, Howell destroyed four of the aircraft and sent a fifth down out of control.[1][5][16] Two days later, Howell was credited with bringing down another plane, forcing the machine to crash down in Allied-held territory. On 15 July, he led a trio of Camels in an assault on sixteen scout planes; he destroyed two of the machines.[5][16] The two scouts were to prove Howell's final aerial victories of the war, bringing his total to nineteen aerial victories which were composed of fifteen aircraft destroyed, three driven down as out of control and one captured.[17] His total made him No. 45 Squadron's second highest-scoring ace after Matthew Frew,[2] although some sources place Howell's score as high as thirty aerial victories.[18][19] Late in July, following ten months of active service in the cockpit, Howell was posted back to the United Kingdom where he spent the remainder of the war attached to training units as a flight instructor.[2][3][10] Cited for his "distinguished and gallant services" in Italy, he was mentioned in the despatch of General Rudolph Lambart, 10th Earl of Cavan on 26 October 1918.[20] For his efforts in destroying eight aircraft over a four-day period in July, Howell was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. A supplement of the London Gazette carried the announcement on 2 November 1918, reading:[16]

Air Ministry, 2nd November, 1918.

His Majesty the KING has been graciously pleased to confer the undermentioned Rewards on Officers and other ranks of the Royal Air Force, in recognition of gallantry in Flying Operations against the Enemy: —

AWARDED THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER.

Lieut. (T./Capt.) Cedric Ernest Howell, M.C., D.F.C.

This officer recently attacked, in company with one other machine, an enemy formation of fifteen aeroplanes, and succeeded in destroying four of them and bringing one down out of control. Two days afterwards he destroyed another enemy machine, which fell in our lines, and on the following day he led three machines against sixteen enemy scouts, destroying two of them. Captain Howell is a very gallant and determined fighter, who takes no account of the enemy's superior numbers in his battles.

England-to-Australia flight and legacy

While stationed in England, Howell attended an investiture ceremony at Buckingham Palace on 13 December 1918, where he was presented with his Distinguished Service Order and Military Cross by King George V.[4] Howell was discharged from the Royal Air Force on 31 July 1919.[21] That year, the Australian Government offered a prize of £10,000 to the first aviator to pilot a British or Commonwealth-built aircraft from England to Australia within a period of 30 days. On 15 August, Howell was approached by British aircraft manufacturer Martinsyde to take part in the race flying their Type A Mk.I aircraft, powered by a Rolls-Royce engine; he accepted the offer.[3][7] He was to be accompanied by Lieutenant George Henry Fraser, a qualified navigator and engineer who had served with the Australian Flying Corps during the war.[3][22]

Howell and Fraser took off in their Martinsyde from Hounslow Heath Aerodrome on 4 December 1919. However, the pair soon ran into poor weather, and were forced to land the aircraft in Dijon, France later that day. Airborne again, they reached Pisa, Italy the following day, where a replacement tail skid was fitted to the A1; by 6 December, the duo were in Naples. On 10 December, Howell and Fraser took off in their fully fuelled plane from Taranto in the afternoon.[3] They intended to reach Africa next, but poor weather conditions forced them to alter their plan and they instead headed for Crete.[7] Their Martinsyde was reported flying over St George's Bay, Corfu at 20:00 that evening. For unknown reasons, Howell and Fraser attempted to execute an emergency landing at Corfu. They were, however, unable to make it to the coast and were forced to crash into the sea.[3][10][23] Citizens in the area later reported that they heard cries for help coming from the sea that night, but a rescue was not possible in the rough conditions.[5] Both Howell and Fraser were drowned.[3][23]

Howell's body later washed ashore and was returned to Australia for burial; Fraser's remains were never discovered.[3] Howell was accorded a funeral with full military honours,[3] which took place at Warringal Cemetery, Heidelberg on 22 April 1920, with several hundred mourners in attendance; his widow, parents and sister were chief among these. A firing party of the Royal Australian Garrison Artillery led the gun carriage bearing the coffin to the cemetery. Captains Adrian Cole, Frank Lukis and Raymond Brownell acted as pallbearers along with five other officers who had served in either the Royal or Australian Flying Corps.[24] On 12 February 1923, a stained-glass window dedicated to the memory of Howell was unveiled by General Sir Harry Chauvel at St. Anselm's Church of England in Middle Park; Howell had been a member of the congregation there in his youth.[7] Following the closure of St. Anselm's in 2001, the window was moved to St. Silas's Church, Albert Park, which is now also the parish church for the former parish of St. Anselm.[25]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Garrisson 1999, pp. 90–91

- 1 2 3 4 5 Franks 2003, p. 83

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Cooke, T. H. (1983). "Howell, Cedric Ernest (1896–1919)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Howell, Cedric Ernest". Records Search. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Newton 1996, pp. 40–41

- 1 2 "Cedric Ernest Howell" (PDF). First World War Embarkation Roll. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Gallant Aviator Honoured". The Argus. 12 February 1923. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ "Captain Howell Lost". The Mercury. 16 December 1919. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ "46th Battalion". Australian military units. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "RAF officers' service records 1918–1919 – Image details – Howell, Cedric Ernest" (fee usually required to view pdf of full original service record). DocumentsOnline. The National Archives. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ↑ "No. 30014". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 April 1917. p. 3467.

- ↑ "No. 30232". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 August 1917. p. 8312.

- 1 2 3 4 "No. 30901". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 September 1918. p. 10968.

- ↑ "No. 30913". The London Gazette (Supplement). 21 September 1918. p. 11252.

- ↑ "No. 30989". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 November 1918. p. 12971.

- 1 2 3 "No. 30989". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 November 1918. pp. 12959–12960.

- ↑ Shores, Franks & Guest 1990, p. 201

- ↑ Grinnell-Milne 1980, p. 223

- ↑ Driggs 2008, p. 293

- ↑ "No. 31106". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 January 1919. p. 287.

- ↑ "No. 31510". The London Gazette. 19 August 1919. p. 10479.

- ↑ "George Henry Fraser". The AIF Project. Australian Defence Force Academy. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- 1 2 Nasht 2006, pp. 85, 92

- ↑ "Late Captain Howell". The Argus. 23 April 1920. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ "History of St Silas, Albert Park". Saint Silas Church, Kentish Town, London, NW5. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

References

- Driggs, Laurence La Tourette (2008). Heroes of Aviation. South Carolina, United States: BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-0-554-53181-6.

- Franks, Norman (2003). Sopwith Camel Aces of World War 1. Osprey Aircraft of the Aces. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-534-1.

- Garrisson, A.D. (1999). Australian Fighter Aces 1914–1953. Fairbairn, Australia: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26540-2. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- Grinnell-Milne, Duncan (1980). Wind in the Wires. New York, United States: Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-12174-6.

- Nasht, Simon (2006). The Last Explorer: Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration. New York, United States: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-825-8.

- Newton, Dennis (1996). Australian Air Aces. Fyshwyck, Australia: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-25-0.

- Shores, Christopher; Franks, Norman; Guest, Russell (1990). Above the Trenches. London, England: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-19-9.