Central Steam Heat Plant | |

| |

| |

| Location | 823 W. Railroad Ave., Spokane, Washington |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 47°39′19″N 117°25′27″W / 47.65528°N 117.42417°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1916 |

| Architect | Cutter & Malmgren |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 96001492[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 13, 1996 |

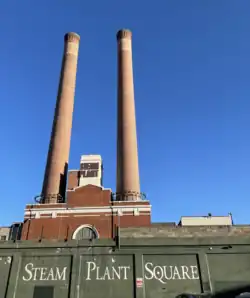

The Central Steam Heat Plant, commonly known as Steam Plant Square, or simply as the Steam Plant, is a historic building in Downtown Spokane, Washington. Originally built to provide steam heating to more than 300 buildings in Spokane's city center, the Steam Plant served that purpose until the 1980s, when it was no longer viable. In the 1990s, the Steam Plant and adjacent Seehorn-Lang Building were converted into Steam Plant Square, a commercial, retail and restaurant center. The conversion maintained many of the industrial steam plant structures such as furnaces, boilers, catwalks and pipe networks, which can still be seen and explored by visitors and patrons. The Steam Plant's pair of 225-foot-tall stacks[2] have been a unique and iconic aspect of the city's skyline for more than a century, and are illuminated from their base at night. If the stacks were considered to be a building, they would rank as the third tallest in the city.[3]

The Steam Plant was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in December 1996, three months after it was listed on the Spokane Register of Historic Places.[4] In 1999, it was listed as a contributing property to the West Downtown Historic Transportation Corridor, a district listed on the NRHP.[5] The property was owned by Avista, the region's energy provider, for more than a century until being sold to a private developer in 2021.[2]

History

Plans for a central heating service in Spokane's city center were made towards the end of an era of explosive growth in the city, which began with rebuilding efforts after the Great Spokane Fire of 1889 and lasted through to World War I. The Steam Plant was one of the last large construction projects reflecting the entrepreneurial spirit of Spokane's boom town days.[6] Spokane businessman Harry A. Flood conceived the idea as a way to economically heat the five buildings his firm owned in the city center. In February 1913, Flood applied to the city with his plans asking to be granted a franchise to realize the idea, and he was granted the franchise in April of the following year. The city mandated that Flood's franchise produce heating for 10 city blocks in the city center as well as to produce electricity. Once the franchise was granted, Flood left his firm and founded the Merchants Central Heating Company of Spokane. By the end of 1915, the Merchants Central Heating Company purchased two lots adjacent to a Northern Pacific railroad from millionaire August Paulsen. A temporary plant was constructed on the site, which provided heat to 38 adjacent buildings including The Davenport Hotel.[6]

In 1916, the Merchants Central Heating Company was dissolved and replaced with the Spokane Heat, Light and Power company, which brought Chicago engineering firm Arnold and Company on to design the permanent Steam Plant structure. The east stack was the first to be completed, in September 1916.[6] Spokane Heat, Light and Power found success in drawing clients for its steam heat, but not for its electricity. As a result, the early days of the Steam Plant saw its ownership heavily indebted to investors, including Pittsburgh's Westinghouse Electric Corporation, which provided the plant's heating equipment. The company was put into receivership and ultimately purchased in 1919 by Washington Water Power,[6] which through its successors owned the Steam Plant until 2021.[2] Washington Water Power administered the Steam Plant through its Spokane Central Heating Company.[6]

Modernization efforts were undertaken in the early-1970s, including pollution-control measures, but they were not enough to maintain cost-effective operations at the plant. Steam pipes crisscrossing downtown had deteriorated as well, adding to the plant's fiscal woes. In the early-1980s the plant's fate was sealed with its impending closure being announced. That closure ultimately came when the final boiler was turned off in December 1986. The building then sat vacant for about a decade[6] until Avista, Washington Water Power's successor, hired local developer Ron Wells to renovate the facility into a mix of restaurant, retail and office space in the late-1990s.[7]

Wells' transformation of the formerly industrial structure into a retail and commercial space known as Steam Plant Square, included the adjacent and historic Seehorn-Lang Building. The renovation was honored with the National Preservation Honor Award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation. A second, smaller renovation was undertaken in 2017 that saw upgrades to its event center. Avista sold the Steam Plant Square complex in 2021 to Spokane developer Jerry Dicker, who owns numerous hotels and historic properties in Spokane including the Bing Crosby Theater and Montvale Block. Dicker plans to continue the development and mixed-use nature of the complex.[7]

Post-industrial use

Steam Plant Square, which comprises the Central Steam Heat Plant building and the neighboring Seehorn-Long Building, is home to a mix of office, retail and restaurant tenants. Ron Wells, who oversaw the redevelopment of the Steam Plant in the late-1990s, told The Spokesman-Review in 2017, "It's a huge gift to Spokane. There's just nothing like it. No other city has saved a steam plant to that degree."[7] Its smoke stacks continue to be viewed as an iconic aspect of the city's skyline, though its contributions to the city are no longer in the realm of utilities, but rather cultural instead. The Steam Plant has hosted a handful of music festivals over the years,[8][9] has been home to numerous locally owned shops,[10] and become a tourist attraction for its unique mix of industrial history and contemporary commerce. Men's Journal named the Steam Plant one of the 10 coolest places to drink craft beer in the United States.[11]

Architecture

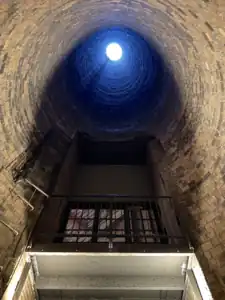

The Steam Plant is a steel-reinforced concrete and brick structure 140 feet long and 83 feet wide. The main building stands three stories tall with a height of 50 feet. The twin smokestacks rise to a height of 225 feet and are located on in the northeast and northwest corners of the building. The stacks have a diameter of 17.5 feet on the outside and 13 feet on their interior. The stacks taper as they rise, but flare at the top, with a diameter of 13.5 feet on the outside and 12 feet on the interior. The north side of the building connects to the adjacent railroad tracks on a raised right of way, which allowed for coal to be unloaded from trains directly into the plant.[6]

On the south façade are five two-story-high arched windows framed with white terra cotta. A five-foot-tall concrete base runs along the street, with bricks composing the bulk of the façade above that. Three of the five windows end at the base, while two have been extended to street level, having been converted into doors. Between the five arched windows and the cornice are five rectangular windows, one above each of the five arched windows. The rectangular windows are separated by bricks, but their white terra cotta sills are connected. The cornice is also made of white terra cotta below a brick parapet.[6] The south façade faces the publicly accessible Steam Plant Alley.[12]

The north façade faces an elevated railroad right of way and served as the connection between the plant and the trains delivering coal. As a result, it is designed for functionality more so than the south façade. Like the south façade, it has a concrete base with bands of horizontally laid bricks above that. At the second story is an entrance and window in the center, similar to the arched windows on the south. The north façade also features a plain white terra cotta cornice with a brick parapet above it. A brick structure with a gabled roof is located above the parapet and between the two smokestacks.[6]

The east and west façades were designed identically, but have been altered with the construction and demolition of adjoining buildings.[6] The east façade formerly abutted offices for the plant, but is now next to an Avista substation.[12] The west façade connects to the Seehorn-Lang Building[6] and serves as the main entrance.

Inside the building is a cavernous space of steel beams, catwalks and staircases. Much of the piping from the plant's time in use remains visible, and the coal bunker suspended in the center is as well.[6] During the renovation in the late 1990s, four boilers in the lower levels were converted into restaurant space, the coal bunker was converted into an office, the west tower was opened to visitors and the east tower was converted into a conference room.[13]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Industrial equipment interior décor

Industrial equipment interior décor Interior stairs and an old tank

Interior stairs and an old tank Looking up above the main entrance

Looking up above the main entrance Office space in the converted coal bunker

Office space in the converted coal bunker View up the west stack

View up the west stack.jpg.webp) View of the south façade

View of the south façade

References

- ↑ "NPGallery Asset Detail". nps.gov. National Park Servie. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Riordan, Kaitlin (May 26, 2021). "After more than a century, Avista sells historic Steam Plant to developer". KREM-TV. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Tallest buildings in Spokane". emporis.com. Emporis. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ↑ "Central Steam Heat Plant". historicspokane.org. City - County of Spokane Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). historicspokane.org. National Park Service. November 23, 1999. p. 6. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). historicspokane.org. National Park Service. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Shanks, Adam (May 21, 2021). "Avista sells Steam Plant to Spokane developer Jerry Dicker". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ↑ Nailen, Dan (April 21, 2017). "Announcing the Volume 2017 lineup; tickets on sale now!". Inlander. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Steam Plant Summer Series". unifestco.com. Unifest. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ↑ Brown, Spencer (October 10, 2018). "Reused and Recycled: on the Steam Plant and what goes on inside the important part of the Spokane Skyline". The Gonzaga Bulletin.

- ↑ Montefiore, Sunny. "The 10 Coolest Places in America to Drink Craft Beer". Men's Journal. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- 1 2 McDermott, Ted (February 24, 2021). "Avista substation relocation could open up redevelopment opportunities downtown". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Steam Plant Square". dci-engineers.com. DCI Engineers. Retrieved July 15, 2022.