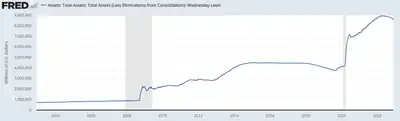

A central bank put (an abbreviation of the central bank put option) is a financial practice where a central bank sets up an effective floor underneath the prices of certain asset classes, recently by offering to buy these assets from private entities outright and requesting no obligation from sellers to compensate the central bank for possible losses.[1] Central bank put is one of the tools central banks use to calm a financial market when it becomes unstable.[2] As long as the country where the central bank is executing the put can avoid a major debasement of its currency, the put is a very effective mean for supporting the collapsing asset prices. Major examples in the 2020s included:[3]

- the purchases of the US Treasury securities in March and April 2020, when the Federal Reserve ended up holding about 5% of the marketable Treasuries and 8% of the Treasury bonds outstanding;

- the purchases of Gilts by the Bank of England that started at the end of September 2022.

The term has been in use since the 1987 market crash (the Federal Reserve lowering the interest rates and providing banks with liquidity in response to this event is also called the "Greenspan put").[4] Some researchers use the term in a more broad sense, describing the central bank that intervenes forcefully when the markets go down and does not react vigorously to the positive results,[5] also applying the term to corresponding (and no longer unreasonable) expectations of investors that the stock market can only go up, since the central bank will be forced to provide funds for a market recovery after a significant decline.[6]

By the end of 2000s the practice became common in the form of quantitative easing (QE). There is a danger of moral hazard[7] in using the central bank put, as it allows the financial dominance, enabling the financial market to manipulate the central bank's policies. The players in the financial markets are extremely good at exploiting the loopholes, so the certainty of the central bank intervention will inevitably cause the appearance of financial instruments created by the players to profit at the central bank's expense.[8] Sissoko suggests that the Liability Driven Investment funds that forced the intervention by the Bank of England in 2022 were actually designed to eventually trigger the Bank's actions: for example, BlackRock, one of the asset managers for the funds, explicitly mentioned Bank of England as a "natural buyer" for the underlying securities, with the only other ones being the pension funds.[9]

Despite the similarities, the central bank put is quite different from the regular market put option:[10]

- the central bank put is an implicit instrument, the strike price is not communicated to the market in advance. Broeders et al. argue that the strike price is supposed to be countercyclical to the changes in the credit spread in the financial markets: in case of QE, the level of spread triggering the sovereign bond purchases is increased when the risk of a market disorder is diminished;[11]

- for a regular put the initiative always stays with the buyer of an option, in the quantitative easing scenario the writer of an option (central bank) decides when the implicit buyers are enabled to execute it. The combination of having the underlying security and a put option makes the prices of the security to react less to the deterioration of the fundamentals;

- there is naturally no explicit premium paid for the central bank put, although Broeders et al. suggested that the effective premium, accrued to the issuer of the security (sovereign in case of a government bond) in the form of lower bond spread due to lower risk,[12] can be estimated through the contingent claim analysis.

Saner is arguing that, as of summer 2022, the interest rates of the major central banks are still very low (way below the ones prescribed by the Taylor rule), so banks will keep increasing the rates, making the strike price of the central bank put "very low".[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Sissoko 2022, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Sissoko 2022, p. 8.

- ↑ Sissoko 2022, p. 9.

- ↑ Herzog 2021, p. 13.

- ↑ Schmeling, Schrimpf & Steffensen 2022, p. 20, preprint version.

- ↑ Sunder 2020, p. 262.

- ↑ Sissoko 2022, p. 1.

- ↑ Sissoko 2022, p. 13.

- ↑ Sissoko 2022, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Broeders, de Haan & van den End 2022, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Broeders, de Haan & van den End 2022, p. 30.

- ↑ Broeders, de Haan & van den End 2022, pp. 21.

- ↑ Saner 2022.

Sources

- Sissoko, Carolyn (2022). "Financial Dominance: Why the 'Market Maker of Last Resort' Is a Bad Idea and What to Do About It". SSRN 4240857.

- Herzog, Bodo (24 March 2021). "Hidden Blemish in European Law: Judgements on Unconventional Monetary Programmes". Laws. 10 (2): 18. doi:10.3390/laws10020018. eISSN 2075-471X.

- Sunder, Shyam (6 July 2020). "How did the U.S. stock market recover from the Covid-19 contagion?". Mind & Society. 20 (2): 261–263. doi:10.1007/s11299-020-00238-0. eISSN 1860-1839. ISSN 1593-7879. PMC 7338109.

- Broeders, Dirk; de Haan, Leo; van den End, Jan Willem (2022). "How QE changes the nature of sovereign risk". SSRN 4031646.

- Schmeling, Maik; Schrimpf, Andreas; Steffensen, Sigurd A.M. (December 2022). "Monetary policy expectation errors". Journal of Financial Economics. 146 (3): 841–858. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2022.09.005. hdl:10419/245996. ISSN 0304-405X. SSRN 3553496.

- Saner, Patrick (21 June 2022). "Goodbye to all that: central banks step into a brave new world". swissre.com. No. 14. Swiss Re Institute. Retrieved 26 November 2022.